| Part of a series on |

| Armenians |

|---|

|

| Armenian culture |

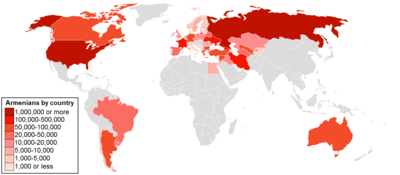

| By country or region |

Armenian diaspora Russia |

| Subgroups |

| Religion |

| Languages and dialects |

| Persecution |

Armenians in Turkey (Turkish: Türkiye Ermenileri; Armenian: Թուրքահայեր, also Թրքահայեր, both meaning Turkish Armenians and Պոլսահայեր, the latter meaning Istanbul-Armenian) have an estimated population of 40,000 (1995) to 70,000.[1][2] Most are concentrated around Istanbul. The Armenians support their own newspapers and schools. The majority belong to the Armenian Apostolic faith, with smaller numbers of Armenian Catholics and Armenian Evangelicals.

History

Armenians living nowadays in Turkey are a remnant of a once much larger community that existed for hundreds of years and long before the establishment of the Ottoman Empire. Estimates for the number of Armenian citizens of the Ottoman Empire in the decade before World War I range between 2 to 2.5 million. During the Ottoman Empire, the Armenians of Turkey were active in business and trade, just like the Greeks and Jews[3] of Turkey.

Starting in the late nineteenth century, political instability, dire economic conditions, and continuing ethnic tensions prompted the emigration of as many as 100,000 Armenians to Europe, the Americas and the Middle East. This massive exodus created the modern Armenian diaspora worldwide based on mainly Ottoman Armenian populations emigrating in large numbers, in addition to some emigration from the Caucasus which was more towards Russia.

In 1894-1897 at least 100,000 Armenians were killed during the Hamidian massacres in 1894, 1895, 1896. Further massacres ensued in 1909, also known as the Adana Massacre, that caused the death of an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 Armenians. The Armenian Genocide[4] followed in 1915-1916 until 1918, during which the Ottoman government of the time ordered the deportation of up to 1.5 to 2 million Armenians allegedly for political and security considerations. These measures effected a huge majority, close to 75%-80% according to estimates, of all the Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Many died directly through Ottoman massacres and atrocities, while others died as a result of mass deportations and forced population movements, and more through unlawful Kurdish militia attacks.

As for the remaining Armenians in the Eastern parts of the country, they found refuge by 1917-1918 in the Caucasus and eventually within the areas controlled by the newly established Democratic Republic of Armenia and never returned to their original homes in Eastern Turkey (composed of the 6 vilayets, namely (Erzurum, Van, Bitlis, Diyarbekir, Kharput, and Sivas.

Some Armenians, about 300,000 according to some estimates were adopted by Turks and Kurds or married with Muslim populations in a process of Turkification and Kurdification to a avoid facing a similar fate.[5][6]

Most of the Armenian survivors ended up in northern Syria and the Middle East in general, with some temporarily returning to their homes in Turkey at the end of World War I particulary during the French Mandate, as a result of France being allocated the control of southeastern Turkey and all of Cilicia according to the Sykes–Picot Agreement. The Armenian population suffered a final blow with ongoing massacres and atrocities throughout the period 1920-1923, the period of the Turkish War of Independence, the ones suffering most being the remnants of the Armenians in the East and the South of the country, as well as the Greeks in the Black Sea Region. Mass deportations of Turkey's surviving Armenian population continued especially after the withdrawal of the French forces from the area. The few remaining Armenians left anyway.

By the end of the 1920s, only a handful number of Armenians were left in Turkey scatterered sparsely throughout the country, with the only viable Armenian populace remaining in Istanbul area and the environs.

Demographics

The present Armenian population is estimated between 40,000 and 70,000 mostly living in Istanbul and the environs. Even the small number of actual Turkish Armenians living in Turkey is diminishing further due to emigration to Europe, Americas and Australia.

The community is recognized as a separate "millet" in the Turkish system and has its own religious, cultural, social and educational institutions and its distinct media. The Turkish Armenian community struggles very hard to keep its own institutions and schools open and media running, against diminishing demand due to emigration and quite considerable economic sacrifices.

The Turkish Armenian community is divided into a majority Apostolic Orthodox Armenians belonging to the Armenian Apostolic Church with a small minority belonging to the Armenian Catholic Church and the Armenian Evangelical Church.

Crypto-Christian Armenian Turks

However many say that the actual number of people of Armenian ethnic origin currently living in Turkey is higher than the official numbers given (40,000-70,000), which comprise Armenians as per the definition of a Christian minority (ekalliyet).

During the Armenian Genocide many Armenian orphans were adopted by local Muslim families, who sometimes changed their names and converted them to Islam. One source cites 300,000[5] but another analysis considers this an overestimate, leaning towards 63,000, the figure cited in the Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople's 1921 report to the United States Department of State.[7]

When relief workers and surviving Armenians started to search for and claim back these Armenian orphans after World War I, only a small percentage were found and reunited, while many others continued to live as Muslims. Additionally, some Armenian families had converted to Islam in order to escape the genocide.

Because of this, there are an unknown number of people of Armenian origin in Turkey today who are not aware of their ancestry as well as around 300,000 "secret" Armenians, called Crypto-Christians.[8] The figure [of 300,000] may have been accurate in 1915, but several generations have passed since then, so figures must be much higher, particularly for mixed heritage. The figure of just how many individuals of some Armenian descent existing in Turkey is hotly disputed, because of the natural progression of populations. But most conservative estimates would put them passed the one-million mark by the late 20th century.

Others dispute the high number of "secret Armenians" of Armenian ethnicity as this may have changed through Turkification by time and through marriage with general Turkish and Kurdish populations and borders of Armenianness may be blurred and many may actually feel more Turkish than Armenian by now.

According to an article by Zaman columnist Erhan Başyurt, İbrahim Ethem Atnur of Atatürk University alleges that the state colluded with the Armenian Patriarchate to artificially increase the Armenian population by raising orphaned Turks as Armenians.[9] In the 1960s, some of these families converted back to Christianity and changed their names.

According to the Armenian Embassy in Canada,[10]

The genocide, as we have seen, destroyed western Armenia and numerous other Armenian centers in Turkey. By the Second World War, Constantinople or Istanbul was the sole urban center with an Armenian presence. In 1945, an arbitrary property tax on the minorities impoverished many Greek and Armenian businessmen. Ten years later, mobs looted and burned Greek and Armenian businesses in Istanbul. At present there are some 75,000 Armenians in Turkey, the majority of whom live in Istanbul, where conditions, despite cultural pressures and occasional hostile acts, are not as unfavorable as one may imagine. Twenty schools, some three dozen churches, and a hospital maintain a strong Armenian identity. A number of Armenian newspapers, including the daily Marmara continue to publish, and Armenian organizations go about collecting donations and sponsoring cultural activities. The Armenian patriarch is also invited to official Turkish state ceremonies. Major problems include the lack of a seminary, Armenian institutions of higher education, and linguistic assimilation.

Journalist Hrant Dink says that the current population of around 50,000 is half of what it was eighty years ago as a result of a deliberate attempt instituted during the Single Party Period to reduce the population of the minorities.[11]

Vakıflı Köyü, Samandağ, an Armenian village in Turkey

Vakıflı Köyü (Armenian: Վաքիֆ — Vakif) is the only remaining ethnic Armenian village in Turkey.[12][13] Located on the slopes of Musa Dagh in the Samandağ district of Hatay Province, the village overlooks the Mediterranean Sea and is within eyesight of the Syrian border. It is home to a community of about 130 Turkish-Armenians.[13]

Hemshins of Armenian origin

File:Hamsheni woman in traditional dress.jpg

The Hemshin Peoples are a number of diverse groups of people who in the past history or present have been affiliated with the Hemşin area[14][15][16] which is in Turkey's eastern Black Sea region.

They are called (and call themselves) as Hemshinli (Turkish: Hemşinli), Hamshenis, Homshentsi (Armenian: Համշենի) meaning resident of Hemshin (historically Hamshen) in the relevant language.[17] The term "The Hemshin" is used also in some publications to refer to Hemshinli.[18][19]

The area was annexed by the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century and during the Ottoman period, there was a process of migrations and Islamization.[20] The details and the accompanying circumstances for the migrations and the Islamization process during the Ottoman era are not clearly known and documented.[21]

Most sources agree however that prior to Ottoman era, the great majority of the residents of Hemshin were mainly ethnic Armenians and members of the Armenian Apostolic Church and practiced Christianity. They also kept a lot of the elements of Armenian ethnicity in their traditions and local language to this day.

As a result of those developments, distinctive communities with the same generic name have also appeared in the vicinity of Hopa, Turkey as well as in the Caucasus. Those three communities are almost oblivious to one another's existence.[22]

Within Turkey, are found the Hemshinli of Hemshin proper (also designated occasionally as western Hemshinli in publications) are Turkish-speaking Sunni Muslims who mostly live in the counties (ilçe) of Çamlihemşin and Hemşin in Turkey's Rize Province.

Also in Turkey are the Hopa Hemshinli (also designated occasionally as eastern Hemshinli in publications) are Sunni Muslims and mostly live in the Hopa and Borçka counties of Turkey's Artvin Province. In addition to Turkish, they speak a dialect of western Armenian they call "Homshetsma" or "Hemşince" in Turkish.[23]

In addition, outside the republic of Turkey, Homshentsik (also designated occasionally as Northern Homshentsik in publications) are Christians who live in Abkhazia and in Russia's Krasnodar Krai. They speak Homshetsma as well.[24] There are also some Muslim Hemshinli living in Georgia and Krasnodar, Russia and some Hemshinli elements amongst the Meskhetian Turks.[25]

Religion

Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople

The Armenian Patriarch of Istanbul established is 1461 is religious head of the Armenian community in Turkey. It has exerted a very significant political role earlier and today still exercises a spiritual authority, which earns it considerable respect among Orthodox churches. The Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople recognizes the primacy of the Supreme Patriarch and Catholicos of All Armenians, in the spiritual and administrative headquarters of the Armenian Church, the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, Vagharshapat, Republic of Armenia, in matters that pertain to the worldwide Armenian Church. In local matters, the Patriarchal See is autonomous.

Archbishop Patriarch Mesrob II Mutafyan of Constantinople is the 84th Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople under the authority of the Supreme Patriarch and Catholicos of All Armenians.

Christmas date, etiquette and customs

Armenians celebrate Christmas at a date later than most of the Christians, on 6th of January rather than 25th of December. The reason for this is historical; according to Armenians, Christians once celebrated Christmas on 6 January, until the 4th century. 25 December was originally a pagan holiday that celebrated the birth of the sun. Many members of the church continued to celebrate both holidays, and the Roman church changed the date of Christmas to be 25 December and declared January 6 to be the date when the three wise men visited the baby Jesus. As the Armenian Apostolic Church had already separated from the Roman church at that time, the date of Christmas remained unchanged for Armenians. [26]

The Armenians in Turkey refer to Christmas as Surp Dzınunt (Holy Birth) and have fifty days of preparation called Hisnag before Christmas. The first, fourth and seventh weeks of Hisnag are periods of vegetarian fast for church members and every Saturday at sunset a new purple candle is lit with prayers and hymns. On the second day of Christmas, 7 January, families visit graves of relatives and say prayers.[27]

Armenian Churches in Turkey

Turkey has hundreds of Armenian churches belonging to various denominations, mainly Armenian Apostolic, but also Armenian Catholic and Armenian Evangelical Protestant churches.[28]

Armenian Apostolic Orthodox Churches in Turkey

Besides Surp Asdvadzadzin Patriarchal Church (translation: the Holy Mother-of-God Armenian Patriarchal Church) in Kumkapi, Istanbul, there are tens of Armenian Apostolic churches. Many of them might be inactive because of lack of the flock or lack of clergy.

In Istanbul:

- Christ The King Armenian Church (Kadikoy, Istanbul)

- Church of the Apparition of the Holy Cross (Kurucesme, Istanbul)

- Holy Archangels Armenian Church (Balat, Istanbul)

- Holy Cross Armenian Church (Kartal, Istanbul)

- Holy Cross Armenian Church (Selamsiz, Uskudar, Istanbul)

- Holy Hripsimiants Virgins Armenian Church (Buyukdere, Istanbul)

- Holy Mother-of-God Armenian Apostolic Church (Bakirkoy, Istanbul)

- Holy Mother-of-God Armenian Church (Besiktas, Istanbul)

- Holy Mother-of-God Armenian Church (Eyup, Istanbul)

- Holy Mother-of-God Armenian Church (Ortakoy, Istanbul)

- Holy Mother-of-God Armenian Church (Yenikoy, Istanbul)

- Holy Nativity of the Mother-of-God Armenian Church (Bakirkoy, Istanbul)

- Holy Resurrection Armenian Church (Kumkapi, Istanbul)

- Holy Resurrection Armenian Chapel (Taksim, Istanbul)

- Holy Three Youths Armenian Church (Boyacikoy, Istanbul)

- Holy Trinity Armenian Church (Galatasaray, Istanbul)

- Narlikapi Armenian Apostolic Church (Narlikapi, Istanbul)

- St. Elijah The Prophet Armenian Church (Eyup, Istanbul)

- St. John the Baptist Armenian Church (Usgudar)

- St. John The Evangelist Armenian Church (Gedikpasa, Istanbul)

- St. John The Evangelist Armenian Church (Narlikapi, Istanbul)

- St. John The Forerunner Armenian Church (Baglarbasi, Uskudar, Istanbul)

- St. George (Sourp Kevork) Armenian Church (Samatya, Istanbul)

- St. Gregory The Enlightener (Sourp Krikor Lousavoritch) (Ghalatya, Istanbul)

- St. Gregory The Enlightener (Sourp Krikor Lousavoritch) Armenian Church (Kuzguncuk, Istanbul)

- St. Gregory The Enlightener (Sourp Krikor Lousavoritch) Armenian Church (Karakoy, Istanbul)

- St. Gregory The Enlightener (Sourp Krikor Lousavoritch) (Kinaliada, Istanbul)

- St. James Armenian Church (Altimermer, Istanbul)

- St. Nicholas Armenian Church (Beykoz, Istanbul)

- St. Nicholas Armenian Church (Topkapi, Istanbul)

- St. Santoukht Armenian Church (Hisar, Istanbul)

- St. Saviour (Sourp Pergitch) Armenian Chapel (Yedikule, Istanbul)

- St. Sergius Armenian Chapel (Balikli, Istanbul)

- St. Stephen Armenian Church (Karakoy, Istanbul)

- St. Stephen Armenian Church (Yesilkoy, Istanbul)

- St. Takavor Armenian Apostolic Church (Kadekoy, Istanbul)

- Saints Thaddeus and Barholomew Armenian Church (Yenikapi, Istanbul)

- St. Trinity (Sourp Yerrortutyoun) Church (Pera, Istanbul)

- St. Vartanants Armenian Church (Ferikoy, Istanbul)

- The Twelve Holy Apostles Armenian Church (Kandilli, Istanbul)

Other areas:

- Holy Forty Martyrs of Sebastea Armenian Church (Iskenderun, Hatay)

- Holy Mother-of-God Armenian Church (Vakiflikoy, Samandag, Hatay)

- St. George (Sourp Kevork) Armenian Church (Derik, Mardin)

- St. Gregory The Enlightener Armenian Church (Kayseri)

- St. Gregory The Enligtener Armenian Church (Kirikhan)

- St. Giragos Armenian Church (Diyarbakir)

- St. Vartanants (Ferikoy)

Armenian Catholic Churches in Turkey

- St. Mary Armenian Catholic Church (Beyoglu, Istanbul).

- St. Jean Chrisostomus Armenian Catholic Church (Taksim, Istanbul)

- St. Leon Armenian Catholic Church (Kadikoy, Istanbul)

- Armenian Catholic Church of Immaculate Conception (Koca Mustafa Pacha, Istanbul)

- St. Saviour Armenian Catholic Church (Karakoy, Istanbul)

- St. Gregory the Illuminator Armenian Catholic Church (Ortakoy, Istanbul)

- St. Paul Armenian Catholic Church (Buyukdere, Istanbul)

- St. John the Baptist Armenian Catholic Church (Yenikoy, Istanbul)

- Assumption Armenian Catholic Church (Buyukada, Istanbul)

The active Armenian Catholic churches remain as follows: The Armenian Archbishopric in Beyoglu, Istanbul located within the St. Mary Armenian Catholic Church, also the St. Jean Chrisostomus Armenian Catholic Church in Taksim, Istanbul and St. Leon Armenian Catholoc Church in Kadikoy, Istanbul.

Armenian Evangelical Churches in Turkey

- Armenian Evangelical Church (Pera, Istanbul)

- Armenian Evangelical Church (Gedik Pasha, Istanbul)

- The first Arm. Evangelical Congregation in the world

Education

Schools are kindergarten through 12th grade (K-12), kindergarten through 8th grade (K-8) or 9th grade through 12th (9-12). Ermeni İlköğretim Okulu means "Armenian primary+secondary school". Ermeni Lisesi means "Armenian high school". Template:Multicol

- K-8

- Aramyan-Uncuyan Ermeni İlköğretim Okulu

- Bezciyan Ermeni İlköğretim Okulu

- Bomonti Ermeni İlköğretim Okulu

- Dadyan Ermeni İlköğretim Okulu

- Kalfayan Cemaran İlköğretim Okulu

- Karagözyan İlköğretim Okulu

- Kocamustafapaşa Anarat Higutyun Ermeni İlköğretim Okulu

- Levon Vartuhyan Ermeni İlköğretim Okulu

- Feriköy Ermeni İlköğretim Okulu

- Nersesyan-Yermonyan Ermeni İlköğretim Okulu

- Pangaltı Anarat Higutyun Ermeni İlköğretim Okulu

- Tarkmanças Ermeni İlköğretim Okulu

- Yeşilköy Ermeni İlköğretim Okulu

| class="col-break " |

- 9-12

- Getronagan Ermeni Lisesi

- Surp Haç Ermeni Lisesi

- K-12

- Esayan Ermeni İlköğretim Okulu ve Lisesi

- Pangaltı Ermeni Lisesi

- Sahakyan-Nunyan Ermeni Lisesi

Template:Multicol-end

Health

Turkish Armenians also have their own long-running hospitals:

- Surp Prgiç Armenian Hospital (Սուրբ Փրկիչ in Armenian - pronounced Sourp Pergitch or St Saviour). It also has its media information bulletin called "Surp Prgiç"

- Surp Agop Armenian Hospital (Սուրբ Յակոբ in Armenian pronounced Sourp Hagop)

Language

Most Turkish Armenians are bilingual and use both Armenian and Turkish languages. The Armenian schools apply the full Turkish curriculum in addition to Armenian subjects, mainly Armenian language, literature and religion.

The Turkish Armenian community stil keeps a strong literary and linguistic tradition and a long-running Armenian-language media.

Western Armenian, originally the Istanbul Armenian dialect

Western Armenian, (Armenian: Արեւեմտահայերէն pronounced Arevmedaheyeren, Armenian: Արեւմտեան աշխարհաբար pronounced Arevmedyan Ashkharhapar, (and earlier known as Armenian: «Թրքահայերէն», namely "Terkahayeren" (Turkish-Armenian)) is one of the two modern dialects of the modern Armenian, an Indo-European language.

The Western Armenian dialect was developed in the early part of the 19th century, based on the Armenian dialect of the Armenians in Istanbul, to replace many of the Armenian dialects spoken throughout Turkey.

It was widely adopted in literary Armenian writing and in Armenian media published in the Ottoman Empire as well as large parts of the Armenian Diaspora and in modern Turkey.

Partly because of this, Istanbul veritably became the cultural and literary center of the Western Armenians in the 19th and early 20th century.

Western Armenian is spoken by the Armenian diaspora, mainly in North America and South America, Europe and most of the Middle East except for Iran, where the Armenian population because of proximiity to Armenia uses Eastern Armenian, while keeping the traditional Mashdotsian spelling. Adoption of Western Armenian is also mainly due to the fact that great majority of the Armenian diaspora in all these areas (Europe, Americas, Middle East) was formed in the 19th and early 20th century through Armenian populations emanating from the Ottoman Empire.

The Western Armenian language is markedly different in grammar, pronunciation and spelling from the Eastern Armenian language spoken in Armenia and Iran although they are both mutually intelligible. Western Armenian in marked difference also still keeps the classical Traditional Armenian orthography known as Mashdotsian Spelling, whereas Eastern Armenian language adopted reformed spelling in the 1920s.

The Western Armenian language is still spoken by the present-day Armenian community in Turkey

Armeno-Turkish, Turkish in Armenian alphabet

From the early 18th century until around 1950, and for almost 250 years, more than 2000 books were printed in the Turkish language using letters of the Armenian alphabet. This is popularly known as Armeno-Turkish.

Not only Armenians read Armeno-Turkish, but also the non-Armenian elite (including the Ottoman Turkish) could actually read the Armenian-alphabet Turkish language texts.

The Armenian alphabet was also used alongside the Arabic alphabet on official documents of the Ottoman Empire, but was written in Ottoman Turkish. For example, the Aleppo edition of the official gazette of the Ottoman Empire, called "Frat" (Turkish and Arabic for the Euphrates) contained a Turkish section of laws printed in Armenian alphabet.

Also very notably, the first novel to be written in the Ottoman Empire was 1851's Akabi Hikayesi, written by Armenian statesman, journalist and novelist Vartan Pasha (Hovsep Vartanian) in Ottoman Turkish, was published with Armenian script. "Akabi Hikayesi depicted an impossible love story between two young people coming from two different communities amidst hostility and adversity.

When the Armenian Duzoglu family managed the Ottoman mint during the reign of Abdülmecid I, they kept records in the Armenian script, but in the Turkish language.

Great collection of Armeno-Turkish could be found in Christian Armenian worship until the late 1950s. The Bible used by many Armenians in the Ottoman Empire was not only the Bible versions printed in Armenian, but also at times the translated Turkish language Bibles using the Armenian alphabet. Usage continued in Armenian church gatherings specially for those who were Turkophones rather than Armenophones. Many of the Christian spiritual songs used in certain Armenian churches were also in Armeno-Turkish.

Armenians and the Turkish language

Armenians played a key role in the promotion of the Turkish language including the reforms of the Turkish language initiated by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

Bedros Keresteciyan, the Ottoman linguist completed the first etymological dictionary of Turkish. Armenians contributed considerably to the development of printing in Turkey: Tokatlı Apkar Tıbir started a printing house in Istanbul in 1567, the historian Eremia Çelebi, Merzifonlu Krikor, Sivaslı Parseh, Hagop Brothers, Haçik Kevorkyan Abraham from Thrace, Eğinli Bogos Arabian, Hovannes Muhendisian Rephael Kazancian were among many. Bogos Arabian issued the first Turkish daily newspaper, Takvim-i Vekayi and its translation in Armenian. Hovannes Muhendisian is known as the "Turkish Gutenberg". Haçik Kevorkyan updated the Ottoman Turkish alphabet. Yervant Mısırlıyan developed and implemented publishing books in installments for the first time in the Ottoman Empire. Kasap Efendi, published the first Comic magazine Diyojen in 1870. [29]

Agop Martayan Dilaçar (1895-1979] was a Turkish Armenian linguist who had great contribution to the reform of Turkish language. He specialized in Turkic languages and was the first Secretary General and head specialist of the Turkish Language Association (TLA) from its establishment in 1932 until 1979. In addition to Armenian and Turkish, Martayan knew English, Greek, Spanish, Latin, German, Russian and Bulgarian. He was invited on September 22, 1932, as a linguistics specialist to the First Turkish Language Congress supervised by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Istepan Gurdikyan (1865-1948), linguist, Turcologist, educator and academic and Kevork Şimkeşyan both ethnic Armenians were also prominent speakers at the first Turkish Language Conference. Agop Martayan Dilaçar continued his work and research on the Turkish language as the head specialist and Secretary General of the newly founded Turkish Language Association in Ankara. Atatürk suggested him the surname Dilaçar (literally meaning language opener), which he accepted. He taught history and language at Ankara University between 1936 and 1951 and was the head advisor of the Türk Ansiklopedisi (Turkish Encyclopedia), between 1942 and 1960. He held his position and continued his research in linguistics at the Turkish Language Association until his death in 1979.

Culture

Armenians keep a rich cultural life in virtually all forms of Turkish art.

In classical opera music and theatre, Toto Karaca was a major figure. In the folk tradition, Udi Hrant Kenkulian was a legendary oud player.

In music, The "Sayat-Nova” choir was founded on April 24, 1971 under the sponsorship of the St. Children’s Church of Istanbul. Besides performing traditional Armenian songs, the group also studies and interprets Armenian folk music. The pan-Turkish Kardeş Türküler cultural and musical formation, in addition to performing a rich selection of Turkish, Kurdish, Georgian, Arabic and gypsy musical numbers, also includes a number of beautiful interpretation of Armenian traditional music in its repertoire. Both formations gave sold-oout concerts in Armenia as part of the Turkish-Armenian Cultural Program, which was made possible with support from USAID.

In photography Ara Güler is a famous photojournalist of Armenian descent, nicknamed "the Eye of Istanbul" or "the Photographer of Istanbul".

In movie acting, special mention should be made of Vahi Öz who appearedin countless movies from the 1940s until late 1960s and Sami Hazinses, who appeared in tens of Turkish movies from the 1950s until the 1990s.

Media

Istanbul is home to a number of long-running and influential Armenian publications. Most notably "Jamanag" and "Marmara" also have a long tradition of keeping alive the Turkish Armenian literature, which is an integral part of the Western Armenian language and Armenian literature.

- Jamanag (Ժամանակ in Armenian meaning time) is a long-running Armenian language daily newspaper published in Istanbul, Turkey. The daily was established in 1908 by Misak Kochounian and has been somewhat a family establishment, given that it has been owned by the Kochounian family since its inception. After Misak Kochounian, it was passed down to Sarkis Kochounian, and since 1992 is edited by Ara Kochounian.

- Marmara, [1] daily in Armenian (Armenian: Մարմարա) (sometimes "Nor Marmara" - New Marmara) is an Armenian-language daily newspaper published since 1940 in Istanbul, Turkey. It was established by Armenian journalist Souren Shamlian. Robert Haddeler took over the paper in 1967. Marmara is published six times a week (except on Sundays). The Friday edition contains a section in Turkish as well. Circulation is reported at 2000 per issue.

- Agos, [2] (Armenian: Ակօս, "Furrow") is a bilingual Armenian weekly newspaper published in Istanbul in Turkish and Armenian. It was established on 5 April 1996. Today, it has a circulation of around 5,000. Besides Armenian and Turkish pages, the newspaper has an on-line English edition too. Hrant Dink was its chief editor from the newspaper's start until his assassination outside of the newspaper's offices in Istanbul in January 2007. Hrant Dink's son Arat Dink served as the executive editor of the weekly after his assassination.

- Lraber Lraber,(Լրաբեր in Armenian) is a trilingual periodical publication in Armenian, Turkish and English languages and is the official organ of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople

Other Armenian media titles include: "Sourp Pergiç" (St. Saviour) the magazine of the Armenian Sourp Pergiç (Pergitch) Hospital, also "Kulis", "Shoghagat", "Norsan" and the humorous "Jbid" (smile in Armenian)

Famous Turkish-Armenians

Turkish Armenians in the Diaspora

Despite leaving their homes in Turkey, the Turkish Armenians traditionally establish their own unions within the Armenian Diaspora. Usually named "Bolsahay Miutyun"s (Istanbul-Armenian Associations), they can be found in their new adopted cities of important Turkish-Armenian populations. We can mention "Organization of Istanbul Armenians of Los Angeles", the "Istanbul Armenian Association in Montreal" etc.

Armenians from Republic of Armenia in Turkey

With the establishment of the Republic of Armenia, and because of economic hardship in the new republic, and the differential in renumeration of work, many Armenian nationals from the republic work in Turkey. The official numbers are not validated, as it is a highly seasonal process, but estimates vary between 40,000[30] and 70,000[31]

Armenians from the modern Republic of Armenia work in Turkey, as temporary residents, but it is alleged also at many times illegally.

In similar fashion, some Turkish nationals work in the Republic of Armenia, mainly in the construction sector.

See also

- General

- Demography

- Hemshin peoples

- Vakıflı, Samandağ, the only remaining ethnic Armenian village in Turkey.

- Personalities

- Media

References

- ^ Turay, Anna. "Tarihte Ermeniler". Bolsohays: Istanbul Armenians. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

((cite web)): External link in|publisher= - ^ Hür, Ayşe (2008-08-31). "Türk Ermenisiz, Ermeni Türksüz olmaz!". Taraf (in Turkish). Retrieved 2008-09-02.

Sonunda nüfuslarını 70 bine indirmeyi başardık.

- ^ Hür, Ayşe (2008-03-02). "Ermeni mallarını kimler aldı?". Taraf (in Turkish). Retrieved 2008-08-27.

Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun kuruluşundan itibaren Müslüman-Türk unsurlar kendilerine sadece çiftçiliği ve askerliği yakıştırmışlar... Gayrı Müslimler de başka yolları kalmadığı için ticaret ve zanaata yönelmişlerdi.

- ^ Extensive bibliography by University of Michigan on the Armenian Genocide

- ^ a b Kaplan, Sefa (2005-09-30). "Son yıllarda bu kadar müspet tepki almadım". Hürriyet (in Turkish). Retrieved 2008-08-28.

Anadolu'da anneanneniz gibi 300 bin kadın bulunduğu söyleniyor.

- ^ (Başyurt 2005). Hrant Dink: "300 bin rakamının abartılı olduğunu düşünmüyorum. Bence daha da fazladır."

- ^ (Başyurt 2005): Evlatlıkların sayısı 300 bin mi, 63 bin mi? ... Ancak, 300 bin rakamı çok abartılı gözüküyor. O dönemde Ermenilerin toplam nüfusunun bir buçuk milyon olmadığı ve hepsinin tehcir kapsamına alınmadığı biliniyor. Bu durumda, 300 bin rakamı 12 yaşından küçük tüm Ermeni çocuklarının rakamından daha yüksek görünüyor.

- ^ (Başyurt 2005): Prof. Cöhce ise, bu konuda daha iddialı. Ermeni mühtedi ve evlatlıklar arasında, 'Kripto Hıristiyanlar' ya da 'Gizli Ermeniler' olduğunu, bunların Müslüman görünüp Gregoryan geleneklerini sürdürdüklerini söylüyor. Cöhce, bu insanlar üzerinde son dönemlerde kimliklerine döndürmek için çalışmalar yapıldığını, yakın gelecekte bunların Ermenilerin hayallerini gerçekleştirmek için kullanılacaklarını ileri sürüyor.

Cöhce: "Türkiye'de yaklaşık 100 bin 'mühtedi' Ermeni var." - ^ (Başyurt 2005): Raporda, Türk çocuğu olduğu hâlde Güllü ve Cemile adındaki iki kız çocuğuyla, Çengelköy'de ikamet eden Yüzbaşı Abidin Bey'in evinden Nimet adındaki bir Türk kızının zorla alıkonarak Ermeni Patrikhanesi'nde üç gün tutulduğu, Müslüman oldukları anlaşıldıktan sonra ailelerine teslim edildikleri, fakat bir süre sonra yeniden kaçırıldıkları kaydediliyor. Yine Üsküdarlı Papaz Samayan Efendi tarafından alıkonan Cevri isimli kızın Türk ve Müslüman olduğu ispatlandığı hâlde teslim edilmediği vurgulanıyor. Türk kızların zorla Hıristiyanlaştırıldığı kaydediliyor. Amaç, Ermeni nüfusunu yüksek göstermek.

See Atnur's Türkiye'de Ermeni Kadınları ve Çocukları Meselesi for details. Through the book, the article also quotes Şeyhülislam Mehmet Nuri Efendi as having written "Bazı kötü niyetliler tarafından birçok Müslüman kızlarının ailelerinden alınarak Patrikhane'ye, Rum ve Ermeni yetimhanelerine nakledildiği bir kısmının da Hıristiyan aileler nezdinde hizmetçi olarak kullanıldığı bilgilerine ulaşıldığını." (January 2, 1922) - ^ Armenians in the Middle East, Armenian Embassy of Canada. Internet Archive copy, February 14, 2003.

- ^ Duzel, Nese (2005-05-23). "Ermeni mallarını kimler aldı?". Radikal (in Turkish). Retrieved 2008-08-28.

Türkiye'de Ermeniler, niye 80 yılda nüfus artışıyla birlikte bugün 1.5 milyon olmadı da, 1920'de 300 bin olan nüfus bugün 50-60 bine düştü? Çünkü azınlıkların azaltılması politikası, devlet yönetiminin temel politikasıydı. CHP'nin 9'uncu raporunu okuyun. Tek parti döneminde azınlıkların nasıl azaltılmasının düşünüldüğünü görün.

- ^ Kalkan, Ersin (2005-07-31). "Türkiye'nin tek Ermeni köyü Vakıflı". Hürriyet (in Turkish). Retrieved 2007-02-22.

((cite news)): Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Campbell, Verity (2007). Turkey. Lonely Planet. ISBN 1741045568.

- ^ Bert Vaux, Hemshinli: The Forgotten Black Sea Armenians, Harvard University, 2001 pp.1-2,4-5

- ^ Peter Alford Andrews, Ethnic Groups in the Republic of Turkey, Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, Wiesbaden, 1989. pp.476-477,483-485,491

- ^ Hovann H. Simonian (Ed.),"The Hemshin: History, society and identity in the Highlands of Northeast Turkey", Routledge, London and New York., pp. 80, 146-147

- ^ Bert Vaux, Hemshinli: The Forgotten Black Sea Armenians, Harvard University, 2001 p. 1

- ^ Hovann H. Simonian (Ed.),"The Hemshin: History, society and identity in the Highlands of Northeast Turkey", Routledge, London and New York.

- ^ M. Dubin and E. Lucas, "Trekking in Turkey", Lonely Planet, page 126

- ^ Hovann H. Simonian (Ed.),"The Hemshin: History, society and identity in the Highlands of Northeast Turkey", Routledge, London and New York., pp. 61,83,340

- ^ Hovann H. Simonian (Ed.),"The Hemshin: History, society and identity in the Highlands of Northeast Turkey", Routledge, London and New York., pp. 20,52, 58,61-66,80

- ^ Hovann Simonian (ed.) "The Hemshin", London, 2007. p. xxi.

- ^ Ibit, Uwe Blasing, "Armenian in the vocabulary and culture of the Turkish Hemshinli".

- ^ Bert Vaux, Hemshinli: The Forgotten Black Sea Armenians, Harvard University, 2001 p. 2

- ^ Alexandre Bennigsen, "Muslims of the Soviet Empire: A Guide", 1986, p.217.

- ^ "Why Do Armenians Celebrate Christmas on 6 January?". Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- ^ "Our New Year and Nativity/Theophany Traditions". Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- ^ Updated list by Istanbul Armenians site about the Armenian churches and cemetaries in Turkey belonging to various Armenian denominations

- ^ Article by Şule Perinçek about contributions of Armenians to Turkish culture

- ^ "Armenians in Turkey". Economist. 2006-11-16. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

Marina Martossian, who has been working illegally for five months as a cleaner, is typical of 40,000 compatriots there.

- ^ Gül, Abdullah (2007-03-27). "Politicizing the Armenian tragedy". Washington Times. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

Today, there are 70,000 Armenian citizens working in Turkey.

Sources

- Başyurt, Erhan (2005-12-26), "Anneannem bir Ermeni'ymiş!", Aksiyon (in Turkish), 577, Feza Gazetecilik A.Ş., retrieved 2008-08-28

This article contains some text originally adapted from the public domain Library of Congress Country Study for Turkey.

External links

General

- Istanbul Armenians site

- Template:PDFlink Tessa Hofmann

- Organization of Istanbul Armenians of Los Angeles

- Ozur Diliyoruz Turkish Apology site

Media

- Agos Armenian weekly newspaper

- Lraper, Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople Bulletin

- Marmara Armenian daily newspaper

| Historic areas of Armenian settlement | ||

|---|---|---|

| Caucasus | ||

| Former Soviet Union | ||

| Americas | ||

| Europe | ||

| Middle East | ||

| Asia | ||

| Africa | ||

| Oceania | ||