Asghar Ali Engineer | |

|---|---|

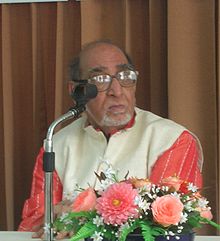

Engineer in 2010 | |

| Born | 10 March 1939 Salumbar, Kingdom of Mewar, British India (now in Rajasthan, India) |

| Died | 14 May 2013 (aged 74) Mumbai, Maharashtra, India |

| Occupation | Writer, activist |

| Notable awards | Right Livelihood Award (2004) |

| Children | 2 |

| Part of a series on Islam Isma'ilism |

|---|

|

|

|

Asghar Ali Engineer (10 March 1939 – 14 May 2013) was an Indian reformist writer and social activist.[1] Internationally known for his work on liberation theology in Islam, he led the Progressive Dawoodi Bohra movement. The focus of his work was on communalism and communal and ethnic violence in India and South Asia. He was a votary of peace and non-violence and lectured all over world on communal harmony.[2]

Engineer also served as head of the Indian Institute of Islamic Studies Mumbai, and the Centre for Study of Society and Secularism (CSSS), both of which he founded in 1980 and 1993 respectively.[3][4] He also made contributions to The God Contention,[5] a website comparing and contrasting various worldviews. Engineer's autobiography A Living Faith: My Quest for Peace, Harmony and Social Change was released in New Delhi on 20 July 2011 by Hamid Ansari, the then vice-president of India.[6]

Asghar Ali Sheikh Kurban (sometimes rendered as Asghar Ali SK) was born 10 March 1939 in Salumbar, Rajasthan, the son of a Bohra priest, Shaikh Qurban Hussain. He was trained in Qur'anic tafsir (commentary), tawil (hidden meaning of Qur'an), fiqh (jurisprudence) and hadith (Prophet's sayings), and learned the Arabic language.[7] He graduated with a degree in civil engineering from Vikram University in Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh,[8] and served for 20 years as an engineer in the Bombay Municipal Corporation. In 1965, he began publishing newspaper articles under the name of "Asghar Ali Engineer." A reviewer explains that

In 1972, Engineer took voluntary retirement in order to devote himself to the Bohra reform movement in the wake of a revolt in Udaipur. He was unanimously elected as General Secretary of The Central Board of Dawoodi Bohra Community in its first conference in Udaipur in 1977. In 2004 due to criticism of the Dawoodi Bohra religious establishment he was expelled. In 1980, he set up the Institute of Islamic Studies in Mumbai to create a platform for progressive Muslims in India and elsewhere. Subsequently, through the 1980s, he wrote extensively on Hindu-Muslim relations, and growing communal violence in India. Asghar Ali Engineer has been instrumental in publicising the Progressive Dawoodi Bohra movement through his writings and speeches. In 1993, he founded 'Center for Study of Society and Secularism (CSSS)' to promote communal harmony.[7] He did not support the ban on Salman Rushdie's "Satanic Verses" though he felt that the novel "is an attack" on religion.[10][11][verification needed]

He authored more than 50 books[12] and many articles in various national and international journals. He was the founding chairman of the Asian Muslim Action Network, director of the Institute of Islamic Studies, and head of the Center for Study of Society and Secularism in Mumbai, where he closely worked with scholar and scientist Professor Dr Ram Puniyani. Engineer was also a supporter of the supporter of the Campaign for the Establishment of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly, an organisation which campaigns for democratic reformation of the United Nations.[13]

Engineer wrote that "Women do not enjoy the status the Qur'an has given them in Muslim society today."[14] Engineer believed that in this day and age women should be equal to men.

Women had internalized their subjugation of men as the latter were the breadwinners. Since then women have become quite conscious of their new status.[15]

Engineer believed that women should be treated as equal to men, and said that people who support an unjust order, or remain silent in view of gross injustices were not religious people. Women's inequality topped his priority list of injustices. However, critics said that his interpretations of the Qur'an were not strong enough to get people to change their beliefs surrounding women's place in Islam. Sikand thought that Engineer's opinion was based on his interpretation of the Qur'an and his outlook on the 21st century instead of the interpretations that the Qur'an has now. “His understanding of Islam is indelibly shaped by his concern for social justice and inter-communal harmony, of course.”[16]

Engineer was given several awards during his lifetime, including the Dalmia Award for communal harmony in 1990, an honorary D.Litt. by the University of Calcutta in 1993, the Communal Harmony Award in 1997 and the Right Livelihood Award in 2004 (with Swami Agnivesh) for his "strong commitment to promote values of co-existence and tolerance".[8]