| |

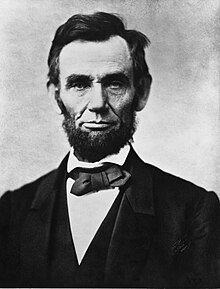

| 16th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865 | |

| Vice President | Hannibal Hamlin Andrew Johnson |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 12, 1809 |

| Died | April 15, 1865 (aged 56) Washington, D.C. |

| Signature | |

The Baltimore Plot was an alleged conspiracy in late February 1861 to assassinate President-elect Abraham Lincoln en route to his inauguration. Allan Pinkerton, founder of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, played a key role by managing Lincoln's security throughout the journey. Though scholars debate whether or not the threat was real, clearly Lincoln and his advisors believed that there was a threat and took actions to ensure his safe passage throughBaltimore, Maryland.

On November 6, 1860, Lincoln was elected as the 16th President of the United States, a Republican, and the first to be elected from that party. Shortly after his election, many representatives of Southern states made it clear that secession was inevitable, which greatly increased tension across the nation. A plot to assassinate Lincoln in Baltimore was alleged. On February 23, 1861, he arrived secretly in Washington, D.C. For the remainder of his presidency Lincoln's many critics would hound him for the seemingly cowardly act of sneaking through Baltimore at night, in disguise, sacrificing his honor for his personal safety. However, the efforts at security may well have been prudent.

Background

Allan Pinkerton was commissioned to provide security for president-elect Lincoln on his journey to Washington, D.C., through Baltimore. Whether or not there was a plot, Maryland was a slave state, and was considered a border state with strong Southern sympathies and was considered dangerous territory through which to travel for such a controversial politician. Two months later, Baltimoreans attacked Union Army soldiers marching to Washington.

Feelings were running high in the other direction as well, and the U.S. government was not about to take risks. Later the same year, many civil liberties were effectively suspended. Pinkerton, in particular, was a very careful man.

Lincoln's actions

On February 11, 1861, President-elect Lincoln boarded an east-bound train in Springfield, Illinois at the start of a whistle stop tour of seventy towns and cities ending with his inauguration in Washington, D.C. Pinkerton had been hired by railroad officials to investigate suspicious activities and acts of destruction of railroad property along Lincoln's route through Baltimore. Pinkerton became convinced that a plot existed to ambush Lincoln's carriage between the Calvert Street Station of the Northern Central and the Camden Street Station of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. This opportunity would present itself during the President-elect's passage through Baltimore on February 23, 1861. Pinkerton tried to convince Lincoln to cancel his stop at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania and to proceed secretly straight through Baltimore, but Lincoln insisted upon keeping to his schedule.

Pinkerton famously clashed with Lincoln’s friend and escort, Ward Hill Lamon, over the President-elect's protection. Lamon offered Lincoln "a Revolver and a Bowie Knife" but Pinkerton protested that he "would not for the world have it said that Mr. Lincoln had to enter the National Capitol armed."[1]

On the evening of February 22 telegraph lines to Baltimore were cut to prevent communications from passing between potential conspirators in Pennsylvania and Maryland. Meanwhile, Lincoln left Harrisburg on a special train and arrived secretly in Baltimore in the middle of the night. The most dangerous link in the journey was in Baltimore where a city ordinance prohibited night-time rail travel through the downtown area. As a result, the railcars had to be horse-drawn between the President Street and Camden Street stations.

According to Pinkerton, a captain of the roads reported that there was a plot to stab him. The alleged plan was to have several assassins, armed with knives, interspersed throughout the crowd that would gather to greet Lincoln at the President Street station. When Lincoln emerged from the car, which he must do to change trains, at least one of the assassins would be able to get close enough to kill him.

Cipriano Ferrandini | |

| Born | 1823 |

| Died | 1910 (Age 87) |

| Occupation(s) | Hairdresser, Southern Sympathizer, alleged conspirator |

Once Lincoln's rail carriage had safely passed through Baltimore, Pinkerton sent a one-line telegram to the president of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad: "Plums delivered nuts safely."

On the afternoon of February 23, Lincoln's scheduled train arrived in Baltimore. The large crowd that gathered at the station to see the President-elect quickly learned that Lincoln had already passed by. Even though the rest of the Lincoln party, including Mrs. Lincoln and the children, had been on this train as originally scheduled, they had already alighted from the train in an unscheduled stop several blocks north of the President Street station. [2][3]

People associated with the alleged plot

- Cipriano Ferrandini - a hairdresser from Corsica who emigrated to the United States, and established himself as the long-time barber and hairdresser in the basement of Barnum's Hotel, in Baltimore. There he practiced his trade from the mid 1850s to his retirement long after the close of the Civil War. He was accused, but never indicted, for plotting to assassinate Abraham Lincoln on February 23, 1861.

- Allan Pinkerton - Head of the Pinkerton Agency

- Kate Warne - female Pinkerton agent who is credited with gathering and supplying information which helped convince Allan Pinkerton that there was a plot to assassinate Lincoln in Baltimore.

- Ward Hill Lamon - personal friend of Lincoln who accompanied him through Baltimore.

- George Proctor Kane - Baltimore's Marshall of Police who protected Mary Todd Lincoln as she passed through the city. He escorted her to the home of John Gittings.

- John Gittings - hosted Mary Todd Lincoln in Baltimore.

- Hattie Lawton - also known as Hattie H. Lawton[4], Lawton was part of Pinkerton's Female Detective Bureau, formed in 1860 to ‘worm out secrets’ by means unavailable to male detectives.

Aftermath - The public's perception of Lincoln's courage

Adalbert J. Volck, Etching,1863

National Portrait Gallery,

Smithsonian Institution

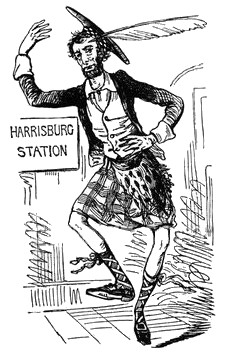

Harper's Weekly, March 9, 1861

Vanity Fair, March 9, 1861

Many historians believe that Pinkerton’s perception of an assassination plot was incorrect and Lincoln came to regret that he slipped through the city unannounced."[5]

Many years after the fact Ward Hill Lamon would publicly argue that there was no plot to assassinate the president in 1861. "It is perfectly manifest that there was no conspiracy -- no conspiracy of a hundred, of fifty, of twenty, of three; no definite purpose in the heart of even one man to murder Mr. Lincoln in Baltimore."[6]

In Lincoln and His Administration, Chittenden argues that there was no need for any precautions, such as a disguise, because Lincoln “entered the sleeping–car at Philadelphia, and slept until awakened within a few miles of Washington.” This account contradicts other first-hand accounts which recount that Lincoln spent a sleepless and anxious night with Lamon and Pinkerton during which he “spoke in a quiet voice to avoid being noticed.”[7]

Legitimate or not, many sources report, “There is little doubt that the feeling and sentiment of the people of Baltimore is very bitter against Mr. Lincoln, so much so, indeed, that violence might have been attempted.”

Whether or not the President-elect was ever in any real danger of being assassinated, Lincoln's efforts to reach Washington, D.C. safely instantly became a humiliating cause célèbre across the nation, much to his chagrin.

Several elements of the initial New York Times article of February 23, 1861 were particularly damning. Primarily, the fact that such a negative report came from an ardently Republican newspaper gave it instant credibility [8] - much more than it would have enjoyed if it had come from a Copperhead or Southern source. When The New York Times published Joseph Howard, Jr.'s account of the President-elect disguised in a scotch-cap and long cloak, the nation "rocked with laughter, bringing abuse and ridicule down on Lincoln." [9]. Substantively, the Howard article was a direct assault on Lincoln's manliness. The article states that Lincoln was reluctant - viz. too scared - to go and was only compelled to go by Colonel Sumner's indignation and by the insistence - viz. shame - of his wife, Mrs. Lincoln, and several others. [10].

The newspapers relentlessly lampooned Lincoln for slipping through Baltimore in the dead of night. Adalbert J. Volck, a Baltimore dentist and caricaturist, was inspired to pen his famous satirical etching, "Passage Through Baltimore." Volck's image of a startled Lincoln in his nightshirt peering out of the side of his rail car as it passes through Baltimore has become part of the Lincoln iconography. "In the nineteenth century, when pictures were less common and more prized, the scotch-cap symbol remained a prop in Confederate graphics, and some Northern-made prints as well, for years - the reminder of Lincoln (sic) fleeing in disguise an automatic accusation of his supposed lack of character."[11]

For the remainder of his presidency the story of his sneaking, like a coward, through Baltimore would be told and retold by his enemies, with particular effect by cartoonists of the day. He was drawn with many variations of Scottish headwear, which eventually morphed into a Scottish balmoral cap and very short kilt. The absurd disguise was frequently accompanied by a terrified expression on the President's face, to further undermine the public's image of his courage and manliness. Images such as this comic strip in Harper's Weekly plagued Lincoln throughout his presidency.

Newspapers of all parties mocked Lincoln's actions, and in a Vanity Fair cartoon, the kilt was traded for a dress the president had borrowed from his wife. By the time Abraham Lincoln arrived in Washington, he was the laughing stock of the entire country.[12]

The New York Tribune was nonetheless forced to admit: "It is the only instance recorded in our history in which the recognized head of a nation... has been compelled, for fear of his life, to enter the capital in disguise." More blunt was the denunciation by the Baltimore Sun:

"Had we any respect for Mr. Lincoln, official or personal, as a man, or as President-elect of the United States... the final escapade by which he reached the capital would have utterly demolished it.... He might have entered Willard's Hotel with a "head spring" and a "summersault," and the clown's merry greeting to Gen. Scott, "Here we are!" and we should care nothing about it, personally. We do not believe the Presidency can ever be more degraded by any of his successors than it has by him, even before his inauguration.[13]

Pratt street riot

The Pratt Street Riot in Baltimore on April 19 and the subsequent arrest and imprisonment of many prominent city residents did little to endear Baltimore to the Union.

Hollywood recreation

In 1951 MGM released a fictional recreation of the alleged plot against Lincoln titled The Tall Target. Its story generally follows what is known about the Baltimore Plot, with some differences. It is a male NYPD detective named John Kennedy, played by Dick Powell, who contacts the administration about the conspiracy, and who boards the train hoping to discover whether any of the plotters are on board before they reach Baltimore. Kennedy discovers a plot that involves a riot to distract police protection away from Lincoln and a sharpshooter armed with a rifle with a telescopic sight to shoot the president-elect. Through Kennedy's efforts, the attempt is aborted and key members of the conspiracy are identified. There actually was an NYPD officer named John Kennedy, who claimed to have the one who uncovered the Baltimore Plot, but he was not actually on scene as Powell's character is in the film. Moreover, in real life, Kennedy was the Superintendent of the entire force. In the film, he is depicted as being a mere detective sergeant.

The film is directed by Anthony Mann and stars Dick Powell, Paula Raymond, Adolphe Menjou, Marshall Thompson, Florence Bates, Will Geer, Victor Kilian, Regis Toomey and Ruby Dee. It is written by George Worthing Yates and Art Cohn and is 78 minutes long. It is also one of just two MGM movies which do not contain a music score of any kind.

See also

- List of United States Presidential assassination attempts

- Abraham Lincoln assassination

- American Civil War spies

- Allan Pinkerton

- Kate Warne

- Ward Hill Lamon

- George Proctor Kane

- Hattie Lawton

- Cipriano Ferrandini

References

- ^ Cuthbert, N: Lincoln and the Baltimore Plot, 1861, page 79. Huntington Library, 1949.

- ^ Scharf, John, History of Maryland vol.III, Tradition Press, p.39

- ^ Arnold, Isaac H. (June to November 1868). "The Baltimore Plot To Assassinate Abraham Lincoln". Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Volume 37. New York: Harper and Brothers. pp. 123–128. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

((cite news)): Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Cuthbert (1949) Lincoln and the Baltimore Plot. p. 4.

- ^ teaching American History

- ^ Lamon, W: Life of Abraham Lincoln, page 513. James R. Osgood and Company, 1872.

- ^ Harris, William C., Lincoln’s Rise to the Presidency. (Lawrence:University of Kansas Press, 2007), 318.

- ^ .Harper pg. 90

- ^ Holzer, Harold, Lincoln Seen & Heard. (University Press of Kansas, 2000.) (pg.118)

- ^ Harper pg. 89&

- ^ Holzer, pg.118

- ^ [1]

- ^ TheHistoryNet | Historical Figures | Abraham Lincoln Takes the Heat

- Cuthbert, Norma Barrett (ed.). Lincoln and the Baltimore Plot, 1861. (1949)

- Evitts, William J., A Matter of Allegiances- Maryland from 1850-1861(Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press,1974)

- Flight of Abraham. Woodcut engraving from Harper's Weekly, New York, March 9, 1861.

- Harper, Robert S., Lincoln and the Press. (McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. New York, 1951.)

- Harris, William C. Lincoln's Rise to the Presidency. (University Press of Kansas, 2000.)

- Holzer, Harold, "Lincoln Seen & Heard." (University Press of Kansas, 2000.)

- Lamon, W: Life of Abraham Lincoln, page 513. (James R. Osgood and Company, 1872.)

- Pinkerton, A. (1883). The Spy of the Rebellion; being a true history of the spy system of the United States Army during the late rebellion. Revealing many secrets of the war hitherto not made public. Comp. from official reports prepared for President Lincoln, General McClellan and the provost-marshal-general. New York, G.W. Carleton & Co. (1883)

- J Hist Dent. 2001 Mar;49(1):17-23. (2001)

- Internet Movie Database

U.S. Cities during the American Civil War | |

|---|---|

| Union | |

| Border states | |

| Confederacy | |