A biological rule or biological law is a generalized law, principle, or rule of thumb formulated to describe patterns observed in living organisms. Biological rules and laws are often developed as succinct, broadly applicable ways to explain complex phenomena or salient observations about the ecology and biogeographical distributions of plant and animal species around the world, though they have been proposed for or extended to all types of organisms. Many of these regularities of ecology and biogeography are named after the biologists who first described them.[1][2]

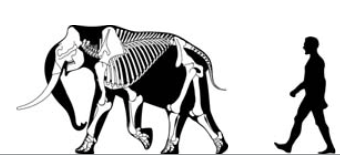

From the birth of their science, biologists have sought to explain apparent regularities in observational data. In his biology, Aristotle inferred rules governing differences between live-bearing tetrapods (in modern terms, terrestrial placental mammals). Among his rules were that brood size decreases with adult body mass, while lifespan increases with gestation period and with body mass, and fecundity decreases with lifespan. Thus, for example, elephants have smaller and fewer broods than mice, but longer lifespan and gestation.[3] Rules like these concisely organized the sum of knowledge obtained by early scientific measurements of the natural world, and could be used as models to predict future observations. Among the earliest biological rules in modern times are those of Karl Ernst von Baer (from 1828 onwards) on embryonic development (see von Baer's laws),[4] and of Constantin Wilhelm Lambert Gloger on animal pigmentation, in 1833 (see Gloger's rule).[5] There is some scepticism among biogeographers about the usefulness of general rules. For example, J.C. Briggs, in his 1987 book Biogeography and Plate Tectonics, comments that while Willi Hennig's rules on cladistics "have generally been helpful", his progression rule is "suspect".[6]

List of biological rules

[edit]

- Allen's rule states that the body shapes and proportions of endotherms vary by climatic temperature by either minimizing exposed surface area to minimize heat loss in cold climates or maximizing exposed surface area to maximize heat loss in hot climates. It is named after Joel Asaph Allen who described it in 1877.[8][9]

- Bateson's rule states that extra legs are mirror-symmetric with their neighbours, such as when an extra leg appears in an insect's leg socket. It is named after the pioneering geneticist William Bateson who observed it in 1894. It appears to be caused by the leaking of positional signals across the limb-limb interface, so that the extra limb's polarity is reversed.[10]

- Bergmann's rule states that within a broadly distributed taxonomic clade, populations and species of larger size are found in colder environments, and species of smaller size are found in warmer regions. It applies with exceptions to many mammals and birds. It was named after Carl Bergmann who described it in 1847.[11][12][13][14][15]

- Cope's rule states that animal population lineages tend to increase in body size over evolutionary time. The rule is named for the palaeontologist Edward Drinker Cope.[16][17]

- Deep-sea gigantism, noted in 1880 by Henry Nottidge Moseley,[18] states that deep-sea animals are larger than their shallow-water counterparts. In the case of marine crustaceans, it has been proposed that the increase in size with depth occurs for the same reason as the increase in size with latitude (Bergmann's rule): both trends involve increasing size with decreasing temperature.[12]

- Dollo's law of irreversibility, proposed in 1893[19] by French-born Belgian paleontologist Louis Dollo states that "an organism never returns exactly to a former state, even if it finds itself placed in conditions of existence identical to those in which it has previously lived ... it always keeps some trace of the intermediate stages through which it has passed."[20][21][22]

- Eichler's rule states that the taxonomic diversity of parasites co-varies with the diversity of their hosts. It was observed in 1942 by Wolfdietrich Eichler, and is named for him.[23][24][25]

Emery's rule states that insect social parasites like cuckoo bumblebees choose closely related hosts, in this case other bumblebees. - Emery's rule, noticed by Carlo Emery, states that insect social parasites are often closely related to their hosts, such as being in the same genus.[26][27]

- Foster's rule, the island rule, or the island effect states that members of a species get smaller or bigger depending on the resources available in the environment.[28][29][30] The rule was first stated by J. Bristol Foster in 1964 in the journal Nature, in an article titled "The evolution of mammals on islands".[31]

- Gause's law or the competitive exclusion principle, named for Georgy Gause, states that two species competing for the same resource cannot coexist at constant population values. The competition leads either to the extinction of the weaker competitor or to an evolutionary or behavioral shift toward a different ecological niche.[32]

- Gloger's rule states that within a species of endotherms, more heavily pigmented forms tend to be found in more humid environments, e.g. near the equator. It was named after the zoologist Constantin Wilhelm Lambert Gloger, who described it in 1833.[5][33]

- Haldane's rule states that if in a species hybrid only one sex is sterile, that sex is usually the heterogametic sex. The heterogametic sex is the one with two different sex chromosomes; in mammals, this is the male, with XY chromosomes. It is named after J.B.S. Haldane.[34]

- Hamilton's rule states that genes should increase in frequency when the relatedness of a recipient to an actor, multiplied by the benefit to the recipient, exceeds the reproductive cost to the actor. This is a prediction from the theory of kin selection formulated by W. D. Hamilton.[35]

- Harrison's rule states that parasite body sizes co-vary with those of their hosts. He proposed the rule for lice,[36] but later authors have shown that it works equally well for many other groups of parasite including barnacles, nematodes,[37][38] fleas, flies, mites, and ticks, and for the analogous case of small herbivores on large plants.[39][40][41]

- Hennig's progression rule states that when considering a group of species in cladistics, the species with the most primitive characters are found within the earliest part of the area, which will be the center of origin of that group. It is named for Willi Hennig, who devised the rule.[6][42]

- Jordan's rule states that there is an inverse relationship between water temperature and meristic characteristics such as the number of fin rays, vertebrae, or scale numbers, which are seen to increase with decreasing temperature. It is named after the father of American ichthyology, David Starr Jordan.[43]

- Kleiber's law states that the metabolic rate of animals and plants scales to 3/4ths the power of their mass. This is named for Max Kleiber, who observed it first in animals in 1932.[44]

Lack's principle matches clutch size to the largest number of young the parents can feed - Lack's principle, proposed by David Lack, states that "the clutch size of each species of bird has been adapted by natural selection to correspond with the largest number of young for which the parents can, on average, provide enough food".[45]

- Rapoport's rule states that the latitudinal ranges of plants and animals are generally smaller at lower latitudes than at higher latitudes. It was named after Eduardo H. Rapoport by G. C. Stevens in 1989.[46]

- Rensch's rule states that, across animal species within a lineage, sexual size dimorphism increases with body size when the male is the larger sex, and decreases as body size increases when the female is the larger sex. The rule applies in primates, pinnipeds (seals), and even-toed ungulates (such as cattle and deer).[47] It is named after Bernhard Rensch, who proposed it in 1950.[48]

- Schmalhausen's law, named after Ivan Schmalhausen, states that a population at the extreme limit of its tolerance in any one aspect is more vulnerable to small differences in any other aspect. Therefore, the variance of data is not simply noise interfering with the detection of so-called "main effects", but also an indicator of stressful conditions leading to greater vulnerability.[49]

- Thorson's rule states that benthic marine invertebrates at low latitudes tend to produce large numbers of eggs developing to pelagic (often planktotrophic [plankton-feeding]) and widely dispersing larvae, whereas at high latitudes such organisms tend to produce fewer and larger lecithotrophic (yolk-feeding) eggs and larger offspring, often by viviparity or ovoviviparity, which are often brooded.[50] It was named after Gunnar Thorson by S. A. Mileikovsky in 1971.[51]Williston's law states that in lineages such as the arthropods, limbs tend to become fewer and more specialised, as shown by the crayfish (right), whereas the more basal trilobites had many similar legs.

- Van Valen's law states that the probability of extinction for species and higher taxa (such as families and orders) is constant for each group over time; groups grow neither more resistant nor more vulnerable to extinction, however old their lineage is. It is named for the evolutionary biologist Leigh Van Valen.[52]

- von Baer's laws, discovered by Karl Ernst von Baer, state that embryos start from a common form and develop into increasingly specialised forms, so that the diversification of embryonic form mirrors the taxonomic and phylogenetic tree. Therefore, all animals in a phylum share a similar early embryo; animals in smaller taxa (classes, orders, families, genera, species) share later and later embryonic stages. This was in sharp contrast to the recapitulation theory of Johann Friedrich Meckel (and later of Ernst Haeckel), which claimed that embryos went through stages resembling adult organisms from successive stages of the scala naturae from supposedly lowest to highest levels of organisation.[53][54][4]

- Williston's law, first noticed by Samuel Wendell Williston, states that parts in an organism tend to become reduced in number and greatly specialized in function. He had studied the dentition of vertebrates, and noted that where ancient animals had mouths with differing kinds of teeth, modern carnivores had incisors and canines specialized for tearing and cutting flesh, while modern herbivores had large molars specialized for grinding tough plant materials.[55]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jørgensen, Sven Erik (2002). "Explanation of ecological rules and observation by application of ecosystem theory and ecological models". Ecological Modelling. 158 (3): 241–248. Bibcode:2002EcMod.158..241J. doi:10.1016/S0304-3800(02)00236-3.

- ^ Allee, W.C.; Schmidt, K.P. (1951). Ecological Animal Geography (2nd ed.). Joh Wiley & sons. pp. 457, 460–472.

- ^ Leroi, Armand Marie (2014). The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science. Bloomsbury. p. 408. ISBN 978-1-4088-3622-4.

- ^ a b Lovtrup, Soren (1978). "On von Baerian and Haeckelian Recapitulation". Systematic Zoology. 27 (3): 348–352. doi:10.2307/2412887. JSTOR 2412887.

- ^ a b Gloger, Constantin Wilhelm Lambert (1833). "5. Abänderungsweise der einzelnen, einer Veränderung durch das Klima unterworfenen Farben". Das Abändern der Vögel durch Einfluss des Klimas [The Evolution of Birds Through the Impact of Climate] (in German). Breslau: August Schulz. pp. 11–24. ISBN 978-3-8364-2744-9. OCLC 166097356.

- ^ a b Briggs, J.C. (1987). Biogeography and Plate Tectonics. Elsevier. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-08-086851-6.

- ^ Sand, Håkan K.; Cederlund, Göran R.; Danell, Kjell (June 1995). "Geographical and latitudinal variation in growth patterns and adult body size of Swedish moose (Alces alces)". Oecologia. 102 (4): 433–442. Bibcode:1995Oecol.102..433S. doi:10.1007/BF00341355. PMID 28306886. S2CID 5937734.

- ^ Allen, Joel Asaph (1877). "The influence of Physical conditions in the genesis of species". Radical Review. 1: 108–140.

- ^ Lopez, Barry Holstun (1986). Arctic Dreams: Imagination and Desire in a Northern Landscape. Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-18578-1.

- ^ Held, Lewis I.; Sessions, Stanley K. (2019). "Reflections on Bateson's rule: Solving an old riddle about why extra legs are mirror-symmetric". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 332 (7): 219–237. Bibcode:2019JEZB..332..219H. doi:10.1002/jez.b.22910. ISSN 1552-5007. PMID 31613418. S2CID 204704335.

- ^ Olalla-Tárraga, Miguel Á.; Rodríguez, Miguel Á.; Hawkins, Bradford A. (2006). "Broad-scale patterns of body size in squamate reptiles of Europe and North America". Journal of Biogeography. 33 (5): 781–793. Bibcode:2006JBiog..33..781O. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01435.x. S2CID 59440368.

- ^ a b Timofeev, S. F. (2001). "Bergmann's Principle and Deep-Water Gigantism in Marine Crustaceans". Biology Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences. 28 (6): 646–650. doi:10.1023/A:1012336823275. S2CID 28016098.

- ^ Meiri, S.; Dayan, T. (2003-03-20). "On the validity of Bergmann's rule". Journal of Biogeography. 30 (3): 331–351. Bibcode:2003JBiog..30..331M. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.2003.00837.x. S2CID 11954818.

- ^ Ashton, Kyle G.; Tracy, Mark C.; Queiroz, Alan de (October 2000). "Is Bergmann's Rule Valid for Mammals?". The American Naturalist. 156 (4): 390–415. doi:10.1086/303400. JSTOR 10.1086/303400. PMID 29592141. S2CID 205983729.

- ^ Millien, Virginie; Lyons, S. Kathleen; Olson, Link; et al. (May 23, 2006). "Ecotypic variation in the context of global climate change: Revisiting the rules". Ecology Letters. 9 (7): 853–869. Bibcode:2006EcolL...9..853M. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00928.x. PMID 16796576. S2CID 13803040.

- ^ Rensch, B. (September 1948). "Histological Changes Correlated with Evolutionary Changes of Body Size". Evolution. 2 (3): 218–230. doi:10.2307/2405381. JSTOR 2405381. PMID 18884663.

- ^ Stanley, S. M. (March 1973). "An Explanation for Cope's Rule". Evolution. 27 (1): 1–26. doi:10.2307/2407115. JSTOR 2407115. PMID 28563664.

- ^ McClain, Craig (2015-01-14). "Why isn't the Giant Isopod larger?". Deep Sea News. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ Dollo, Louis (1893). "Les lois de l'évolution" (PDF). Bull. Soc. Belge Geol. Pal. Hydr. VII: 164–166.

- ^ Gould, Stephen J. (1970). "Dollo on Dollo's law: irreversibility and the status of evolutionary laws". Journal of the History of Biology. 3 (2): 189–212. doi:10.1007/BF00137351. PMID 11609651. S2CID 45642853.

- ^ Goldberg, Emma E.; Boris Igić (2008). "On phylogenetic tests of irreversible evolution". Evolution. 62 (11): 2727–2741. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00505.x. PMID 18764918. S2CID 30703407.

- ^ Collin, Rachel; Maria Pia Miglietta (2008). "Reversing opinions on Dollo's Law". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 23 (11): 602–609. Bibcode:2008TEcoE..23..602C. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.06.013. PMID 18814933.

- ^ Eichler, Wolfdietrich (1942). "Die Entfaltungsregel und andere Gesetzmäßigkeiten in den parasitogenetischen Beziehungen der Mallophagen und anderer ständiger Parasiten zu ihren Wirten" (PDF). Zoologischer Anzeiger. 136: 77–83. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-03-04. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

- ^ Klassen, G. J. (1992). "Coevolution: a history of the macroevolutionary approach to studying host-parasite associations". Journal of Parasitology. 78 (4): 573–87. doi:10.2307/3283532. JSTOR 3283532. PMID 1635016.

- ^ Vas, Z.; Csorba, G.; Rozsa, L. (2012). "Evolutionary co-variation of host and parasite diversity – the first test of Eichler's rule using parasitic lice (Insecta: Phthiraptera)" (PDF). Parasitology Research. 111 (1): 393–401. doi:10.1007/s00436-012-2850-9. PMID 22350674. S2CID 14923342.

- ^ Richard Deslippe (2010). "Social Parasitism in Ants". Nature Education Knowledge. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

In 1909, the taxonomist Carlo Emery made an important generalization, now known as Emery's rule, which states that social parasites and their hosts share common ancestry and hence are closely related to each other (Emery 1909).

- ^ Emery, Carlo (1909). "Über den Ursprung der dulotischen, parasitischen und myrmekophilen Ameisen". Biologisches Centralblatt (in German). 29: 352–362.

- ^ Juan Luis Arsuaga, Andy Klatt, The Neanderthal's Necklace: In Search of the First Thinkers, Thunder's Mouth Press, 2004, ISBN 1-56858-303-6, ISBN 978-1-56858-303-7, p. 199.

- ^ Jean-Baptiste de Panafieu, Patrick Gries, Evolution, Seven Stories Press, 2007, ISBN 1-58322-784-9, ISBN 978-1-58322-784-8, p 42.

- ^ Lomolino, Mark V. (February 1985). "Body Size of Mammals on Islands: The Island Rule Reexamined". The American Naturalist. 125 (2): 310–316. doi:10.1086/284343. JSTOR 2461638. S2CID 84642837.

- ^ Foster, J.B. (1964). "The evolution of mammals on islands". Nature. 202 (4929): 234–235. Bibcode:1964Natur.202..234F. doi:10.1038/202234a0. S2CID 7870628.

- ^ Hardin, Garrett (1960). "The competitive exclusion principle" (PDF). Science. 131 (3409): 1292–1297. Bibcode:1960Sci...131.1292H. doi:10.1126/science.131.3409.1292. PMID 14399717. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-11-17. Retrieved 2017-01-10.

- ^ Zink, R.M.; Remsen, J.V. (1986). "Evolutionary processes and patterns of geographic variation in birds". Current Ornithology. 4: 1–69.

- ^ Turelli, M.; Orr, H. Allen (May 1995). "The Dominance Theory of Haldane's Rule". Genetics. 140 (1): 389–402. doi:10.1093/genetics/140.1.389. PMC 1206564. PMID 7635302.

- ^ Queller, D.C.; Strassman, J.E. (2002). "Quick Guide: Kin Selection". Current Biology. 12 (24): R832. doi:10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01344-1. PMID 12498698.

- ^ Harrison, Launcelot (1915). "Mallophaga from Apteryx, and their significance; with a note on the genus Rallicola" (PDF). Parasitology. 8: 88–100. doi:10.1017/S0031182000010428. S2CID 84334233. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-11-07. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

- ^ Morand, S.; Legendre, P.; Gardner, SL; Hugot, JP (1996). "Body size evolution of oxyurid (Nematoda) parasites: the role of hosts". Oecologia. 107 (2): 274–282. Bibcode:1996Oecol.107..274M. doi:10.1007/BF00327912. PMID 28307314. S2CID 13512689.

- ^ Morand, S.; Sorci, G. (1998). "Determinants of life-history evolution in nematodes". Parasitology Today. 14 (5): 193–196. doi:10.1016/S0169-4758(98)01223-X. PMID 17040750.

- ^ Harvey, P.H.; Keymer, A.E. (1991). "Comparing life histories using phylogenies". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 332 (1262): 31–39. Bibcode:1991RSPTB.332...31H. doi:10.1098/rstb.1991.0030.

- ^ Morand, S.; Hafner, M.S.; Page, R.D.M.; Reed, D.L. (2000). "Comparative body size relationships in pocket gophers and their chewing lice". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 70 (2): 239–249. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2000.tb00209.x.

- ^ Johnson, K.P.; Bush, S.E.; Clayton, D.H. (2005). "Correlated evolution of host and parasite body size: tests of Harrison's rule using birds and lice". Evolution. 59 (8): 1744–1753. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2005.tb01823.x. PMID 16329244.

- ^ "Centers of Origin, Vicariance Biogeography". The University of Arizona Geosciences. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ McDowall, R. M. (March 2008). "Jordan's and other ecogeographical rules, and the vertebral number in fishes". Journal of Biogeography. 35 (3): 501–508. Bibcode:2008JBiog..35..501M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2007.01823.x.

- ^ Kleiber, M. (1932-01-01). "Body size and metabolism". Hilgardia. 6 (11): 315–353. doi:10.3733/hilg.v06n11p315. ISSN 0073-2230.

- ^ Lack, David (1954). The regulation of animal numbers. Clarendon Press.

- ^ Stevens, G. C. (1989). "The latitudinal gradients in geographical range: how so many species co-exist in the tropics". American Naturalist. 133 (2): 240–256. doi:10.1086/284913. S2CID 84158740.

- ^ Fairbairn, D.J. (1997). "Allometry for Sexual Size Dimorphism: Pattern and Process in the Coevolution of Body Size in Males and Females". Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 28 (1): 659–687. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.28.1.659.

- ^ Rensch, Bernhard (1950). "Die Abhängigkeit der relativen Sexualdifferenz von der Körpergrösse". Bonner Zoologische Beiträge. 1: 58–69.

- ^ Lewontin, Richard; Levins, Richard (2000). "Schmalhausen's Law". Capitalism, Nature, Socialism. 11 (4): 103–108. doi:10.1080/10455750009358943. S2CID 144792017.

- ^ Thorson, G. 1957 Bottom communities (sublittoral or shallow shelf). In "Treatise on Marine Ecology and Palaeoecology" (Ed J.W. Hedgpeth) pp. 461-534. Geological Society of America.

- ^ Mileikovsky, S. A. 1971. Types of larval development in marine bottom invertebrates, their distribution and ecological significance: a reevaluation. Marine Biology 19: 193-213

- ^ "Leigh Van Valen, evolutionary theorist and paleobiology pioneer, 1935-2010". University of Chicago. 20 October 2010.

- ^ Opitz, John M.; Schultka, Rüdiger; Göbbel, Luminita (2006). "Meckel on developmental pathology". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 140A (2): 115–128. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.31043. PMID 16353245. S2CID 30513424.

- ^ Garstang, Walter (1922). "The Theory of Recapitulation: A Critical Re-statement of the Biogenetic Law". Journal of the Linnean Society of London, Zoology. 35 (232): 81–101. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1922.tb00464.x.

- ^ Williston, Samuel Wendall (1914). Water Reptiles of the Past and Present. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.