Cthulhu is a fictional character that first appeared in the short story "The Call of Cthulhu", published in the pulp magazine Weird Tales in 1928. The character was created by writer H. P. Lovecraft.

Publication history

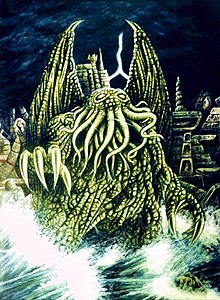

HP Lovecraft's initial short story, The Call of Cthulhu, was published in Weird Tales in 1928 and established the character as a malevolent entity trapped in an arctic underwater city called R'lyeh. Described as being "...an octopus, a dragon, and a human caricature.... A pulpy, tentacled head surmounted a grotesque scaly body with rudimentary wings",[1] and "a mountain walked or stumbled",[2] the imprisoned Cthulhu is apparently the source of considerable disquiet on man's subconscious level, and is the subject of worship by a number of evil cults throughout the world (the short story features the phrase "Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah'nagl fhtagn", which translates as "In his house at R'lyeh, dead Cthulhu waits dreaming."[3]).

The character is a central figure in Lovecraft literature,[4] with the short story The Dunwich Horror (1928)[5] mentioning Cthulhu, while The Whisperer in Darkness (1930) hints at the character's origins ("I learned whence Cthulhu first came, and why half the great temporary stars of history had flared forth.").[6] The 1931 novella At the Mountains of Madness refers to the "star-spawn of Cthulhu", who warred with another race called the Old Ones before the dawn of man.[7]

August Derleth, a contemporary correspondent of Lovecraft, used the creature's name to identify the system of lore employed by Lovecraft and his literary successors: the Cthulhu Mythos. In 1937, Derleth wrote the short story The Return Of Hastur, and proposed two groups of opposed cosmic entities:

...the Old or Ancient Ones, the Elder Gods, of cosmic good, and those of cosmic evil, bearing many names, and themselves of different groups, as if associated with the elements and yet transcending them: for there are the Water Beings, hidden in the depths; those of Air that are the primal lurkers beyond time; those of Earth, horrible animate survivors of distant eons.[8]

According to Derleth's scheme, "Great Cthulhu is one of the Water Beings" and was engaged in an age-old arch-rivalry with a designated Air elemental, Hastur the Unspeakable, described as Cthulhu's "half-brother".[9] Based on this framework, Derleth wrote a series of short stories published in Weird Tales from 1944-1952 and collected as The Trail of Cthulhu, depicting the struggle of a Dr. Laban Shrewsbury and his associates against Cthulhu and his minions.

Derleth's interpretations have been criticised by Lovecraft enthusiast Michel Houellebecq. Houellebecq's H P Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life (2005), decries Derleth for attempting to reshape Lovecraft's strictly amoral continuity into a stereotypical conflict between forces of objective good and evil.[10]

The character's influence also extended into recreational literature: games company TSR included an entire chapter on the Cthulu mythos (including statistics for the character) in the first printing of Dungeons & Dragons sourcebook Deities & Demigods (1980). TSR, however, were unaware that Arkham House - copyright holder on almost all Lovecraft literature - had already licensed the Cthulhu property to the game company Chaosium. Although Chaosium stipulated that TSR could continue to use the material if each future edition featured a published credit to Chaosium, TSR refused and the material was removed from all subsequent editions.[11]

Cult of Cthulhu

Cthulhu is written as having a worldwide doomsday cult centered in Arabia, with followers in regions as far-flung as Greenland and Louisiana.[12] There are leaders of the cult "in the mountains of China" who are said to be immortal. Cthulhu is described by some of these cultists as the "great priest" of "the Great Old Ones who lived ages before there were any men, and who came to the young world out of the sky."[13]

One cultist, known as Old Castro, provides the most elaborate information given in Lovecraft's fiction about Cthulhu. The Great Old Ones, according to Castro, had come from the stars to rule the world in ages past.

They were not composed altogether of flesh and blood. They had shape...but that shape was not made of matter. When the stars were right, They could plunge from world to world through the sky; but when the stars were wrong, They could not live. But although They no longer lived, They would never really die. They all lay in stone houses in Their great city of R'lyeh, preserved by the spells of mighty Cthulhu for a glorious resurrection when the stars and the earth might once more be ready for Them.[14]

Castro points to a "much-discussed couplet" from Abdul Alhazred's Necronomicon:

That is not dead which can eternal lie.

And with strange aeons even death may die.[15]

Castro explains the role of the Cthulhu Cult, stating that when the stars and the earth "might once more be ready" for the Great Old Ones, "some force from outside must serve to liberate their bodies. The spells that preserved Them intact likewise prevented them from making an initial move."[14] At the proper time,

the secret priests would take great Cthulhu from his tomb to revive His subjects and resume his rule of earth....Then mankind would have become as the Great Old Ones; free and wild and beyond good and evil, with laws and morals thrown aside and all men shouting and killing and revelling in joy. Then the liberated Old Ones would teach them new ways to shout and kill and revel and enjoy themselves, and all the earth would flame with a holocaust of ecstasy and freedom.[16]

The character goes on to report that the Great Old Ones are telepathic and "knew all that was occurring in the universe". They were able to communicate with the first humans by "moulding their dreams", thus establishing the Cthulhu Cult, but after R'lyeh had sunk beneath the waves, "the deep waters, full of the one primal mystery through which not even thought can pass, had cut off the spectral intercourse."[17]

Additionally, The Shadow Over Innsmouth establishes that Cthulhu is also worshipped by the nonhuman creatures known as Deep Ones.[18] “The Whisperer in Darkness” establishes that Cthulhu is one of many deities worshiped by the Mi-Go.

Legacy

Games

The character appears prominently in a number of games set in the Lovecraftian world, including the board game Arkham Horror (1987), role-playing edition Call of Cthulhu (Chaosium, 1981); and the card game Call of Cthulhu (Fantasy Flight Games, 2004). The humorous card game Munchkin (Steve Jackson Games, 2001) features a series of parody expansion sets based on the Cthulhu mythos.[19] The character is also the main protagonist in the Xbox 360 video game Cthulhu Saves the World (Zeboyd Games, 2010)[20]

Science

A Californian spider species Pimoa cthulhu, described by Gustavo Hormiga in 1994 is named in reference to Cthulhu.[21]

Music

Among Metallica's several songs drawing on the Cthulhu Mythos is The Call of Ktulu, an instrumental based on "The Call of Cthulhu".[22]

Television

Cthulhu appears as a named character sourced directly to Lovecraft's literature in a Season 1 episode of The Real Ghostbusters, titled "The Collect Call of Cathulhu" [sic].

Visual arts

Artist Stephen Hickman created a statue of the character which was featured in the Spectrum annual,[23] and is exhibited in the John Hay Library of Brown University of Providence.

See also

Notes

- ^ H. P. Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", The Dunwich Horror and Others, p. 127.

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", pp. 152–153.

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu," p. 136.

- ^ "Cthulhu Elsewhere in Lovecraft," Crypt of Cthulhu #9

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Dunwich Horror", The Dunwich Horror and Others, p. 170.

- ^ "Lovecraft, "The Whisperer in Darkness"". Mythostomes.com. 2007-04-09. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- ^ Lovecraft, At the Mountains of Madness, in At the Mountains of Madness, p. 66.

- ^ August Derleth, "The Return of Hastur", The Hastur Cycle, Robert M. Price, ed., p. 256.

- ^ Derleth, "The Return of Hastur", pp. 256, 266.

- ^ Bloch, Robert, "Heritage of Horror", The Best of H. P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre

- ^ "Deities & Demigods, Legends & Lore". The Acaeum. Retrieved 2010-05-10.

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", pp. 133–141, 146.

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", p. 139.

- ^ a b Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", p. 140.

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", p. 141. The couplet appeared earlier in Lovecraft's story "The Nameless City", in Dagon and Other Macabre Tales, p. 99.

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu," p. 141.

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", pp. 140–141.

- ^ Lovecraft, The Shadow Over Innsmouth, pp. 337, 367.

- ^ McElroy, Matt (May 12, 2008). "Munchkin Cthulhu Review". Flames Rising. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- ^ http://zeboyd.com/2010/06/11/cthulhu-saves-the-world-press-release/

- ^ Hormiga, G. (1994). A revision and cladistic analysis of the spider family Pimoidae (Araneoidea: Araneae) (PDF). Vol. 549. pp. 1–104.

((cite book)):|journal=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.sodabob.com/Metallica/Cthulhu.asp

- ^ Burnett, Cathy "Spectrum No. 3:The Best in Contemporary Fantastic Art"

References

- Bloch, Robert (1982). "Heritage of Horror". The Best of H. P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre (1st ed.). Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-35080-4.

- Burleson, Donald R. (1983). H. P. Lovecraft, A Critical Study. Westport, CT / London, England: Greenwood Press. ISBN.

- Burnett, Cathy (1996). Spectrum No. 3:The Best in Contemporary Fantastic Art. Nevada City, CA, 95959 USA: Underwood Books. ISBN 1-887424-10-5.

((cite book)): CS1 maint: location (link) - Harms, Daniel (1998). "Cthulhu". The Encyclopedia Cthulhiana (2nd ed.). Oakland, CA: Chaosium. pp. 64–7. ISBN.

- – "Idh-yaa", p. 148. Ibid.

- – "Star-spawn of Cthulhu", pp. 283 – 4. Ibid.

- Joshi, S. T. (2001). An H. P. Lovecraft Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN.

((cite book)): Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Lovecraft, Howard P. (1999) [1928]. "The Call of Cthulhu". In S. T. Joshi (ed.) (ed.). The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories. London, UK; New York, NY: Penguin Books. ISBN.

((cite book)):|editor=has generic name (help); External link in|chapter= - Lovecraft, Howard P. (1968). Selected Letters II. Sauk City, WI: Arkham House. ISBN.

- Lovecraft, Howard P. (1976). Selected Letters V. Sauk City, WI: Arkham House. ISBN -X.

((cite book)): Check|isbn=value: length (help) - Marsh, Philip. R'lyehian as a Toy Language – on psycholinguistics. Lehigh Acres, FL 33970-0085 USA: Philip Marsh.

((cite book)): CS1 maint: location (link) - Mosig, Yozan Dirk W. (1997). Mosig at Last: A Psychologist Looks at H. P. Lovecraft (1st ed.). West Warwick, RI: Necronomicon Press. ISBN.

- Pearsall, Anthony B. (2005). The Lovecraft Lexicon (1st ed.). Tempe, AZ: New Falcon Pub. ISBN.

- "Other Lovecraftian Products", The H.P. Lovecraft Archive

External links

- Cthulhu Lives, the Lovecraft Historical Society

- Satellite map showing both locations of R'lyeh on the Legends and Sea Stories layer of BlooSee