The Divine Comedy has been a source of inspiration for artists, musicians, and authors since its appearance in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Works are included here if they have been described by scholars as relating substantially in their structure or content to the Divine Comedy.

The Divine Comedy (Italian: Divina Commedia) is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun c. 1308 and completed in 1320, a year before his death in 1321. Divided into three parts: Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory), and Paradiso (Heaven), it is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature[1] and one of the greatest works of world literature.[2] The poem's imaginative vision of the afterlife is representative of the medieval worldview as it had developed in the Catholic Church by the 14th century. It helped to establish the Tuscan language, in which it is written, as the standardized Italian language.[3]

|

Further information: English translations of Dante's Divine comedy |

|

Further information: Francesca da Rimini |

|

Further information: Francesca da Rimini |

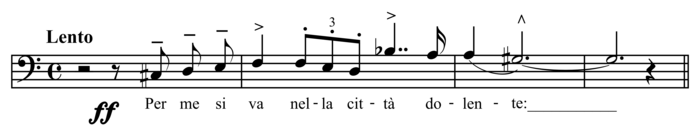

By 1995, the Divine Comedy had been set to music over 120 times; Gioacchino Rossini created two such settings. Only 8 of the settings are of the complete Commedia, "the most famous"[66] being Liszt's symphony; others have composed music for some of Dante's characters, while yet others have set passages of the Commedia to music.[66]

Several aspects of the Divine Comedy could have influenced some tabletop role-playing games: the visitation of other worlds (more specifically plane walking through them), a gamified economy of the salvation, and symbolism.[112]