| |

| Other short titles | Endangered Species Act of 1973 |

|---|---|

| Long title | An Act to provide for the conservation of endangered and threatened species of fish, wildlife, and plants, and for other purposes. |

| Acronyms (colloquial) | ESA |

| Nicknames | Endangered Species Conservation Act |

| Enacted by | the 93rd United States Congress |

| Effective | December 27, 1973 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | 93–205 |

| Statutes at Large | 87 Stat. 884 |

| Codification | |

| Titles amended | 16 U.S.C.: Conservation |

| U.S.C. sections created | 16 U.S.C. ch. 35 § 1531 et seq. |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| Major amendments | |

| United States Supreme Court cases | |

| Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555 (1992) Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill, 437 U.S. 153 (1978) | |

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA or "The Act"; 16 U.S.C. § 1531 et seq.) is the primary law in the United States for protecting imperiled species. Designed to protect critically imperiled species from extinction as a "consequence of economic growth and development untempered by adequate concern and conservation", the ESA was signed into law by President Richard Nixon on December 28, 1973. The U.S. Supreme Court called it “the most comprehensive legislation for the preservation of endangered species enacted by any nation.”[1] The purposes of the ESA are two-fold: to prevent extinction and to recover species to the point the law's protections are not needed. It therefore “protect[s] species and the ecosystems upon which they depend" through different mechanisms. For example, section 4 requires the agencies overseeing the Act to designate imperiled species as threatened or endangered. Section 9 prohibits unlawful ‘take,’ of such species, which means to “harass, harm, hunt...” Section 7 directs federal agencies to use their authorities to help conserve listed species. The Act also serves as the enacting legislation to carry out the provisions outlined in The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).[2] The U.S. Supreme Court found that "the plain intent of Congress in enacting" the ESA "was to halt and reverse the trend toward species extinction, whatever the cost."[1] The Act is administered by two federal agencies, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS).[3] FWS and NMFS have been delegated the authority to promulgate rules in the Code of Federal Regulations to implement the provisions of the Act.

History

Calls for wildlife conservation in the United States increased in the early 1900s because of the visible decline of several species. One example was the near-extinction of the bison, which used to number in the tens of millions. Similarly, the extinction of the passenger pigeon, which numbered in the billions, also caused alarm.[4] The whooping crane also received widespread attention as unregulated hunting and habitat loss contributed to a steady decline in its population. By 1890, it had disappeared from its primary breeding range in the north central United States.[5] Scientists of the day played a prominent role in raising public awareness about the losses. For example, George Bird Grinnell highlighted bison decline by writing articles in Forest and Stream.[6] wrote articles on the subject in the magazine Forest and Stream.

To address these concerns, Congress enacted the Lacey Act of 1900. The Lacey Act was the first federal law that regulated commercial animal markets.[7] It also prohibited the sale of illegally killed animals between states. Other legislation followed, including the Migratory Bird Conservation Act, a 1937 treaty prohibiting the hunting of right and gray whales, and the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act of 1940.

Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966

Despite these treaties and protections, many populations still continued to decline. By 1941, only an estimated 16 whooping cranes remained in the wild.[8] By 1963, the bald eagle, the U.S. national symbol, was in danger of extinction. Only around 487 nesting pairs remained.[9] Loss of habitat, shooting, and DDT poisoning contributed to its decline.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service tried to prevent the extinction of these species. Yet, it lacked the necessary Congressional authority and funding.[10] In response to this need, Congress passed the Endangered Species Preservation Act (P.L. 89-669 on October 15, 1966. The Act initiated a program to conserve, protect, and restore select species of native fish and wildlife.[11] As a part of this program, Congress authorized the Secretary of the Interior to acquire land or interests in land that would further the conservation of these species.[12]

The Department of Interior issued the first list of endangered species in March 1967. It included 14 mammals, 36 birds, 6 reptiles, 6 amphibians, and 22 fish.[13] A few notable species listed in 1967 included the grizzly bear, American alligator, Florida manatee, and bald eagle. The list included only vertebrates at the time because the Department of Interior's limited definition of "fish and wildlife."[12]

Endangered Species Conservation Act of 1969

The Endangered Species Conservation Act of 1969 (P. L. 91–135) amended the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966. It established a list of species in danger of worldwide extinction. It also expanded protections for species covered in 1966 and added to the list of protected species. While the 1966 Act only applied to ‘game’ and wild birds, the 1969 Act also protected mollusks and crustaceans. Punishments for poaching or unlawful importation or sale of these species were also increased. Any violation could result in a $10,000 fine or up to one year of jail time.[14]

Notably, the Act called for an international convention or treaty to conserve endangered species.[15] A 1963 IUCN resolution called for a similar international convention.[16] In February, 1973 a meeting in Washington D.C. was convened. This meeting produced the comprehensive multilateral treaty known as CITES or the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.[17]

The Endangered Species Conservation Act of 1969 provided a template for the Endangered Species Act of 1973 by using the term “based on the best scientific and commercial data.” This standard is used as a guideline to determine if a species is in danger of extinction.

Endangered Species Act of 1973

In 1972, President Richard Nixon declared current species conservation efforts to be inadequate.[18] He called on the 93rd United States Congress to pass comprehensive endangered species legislation. Congress responded with the Endangered Species Act of 1973, which was signed into law by Nixon on December 28, 1973 (Pub.L. 93–205).

The ESA is considered a landmark conservation law. Academic researchers have referred to it as “one of the nation's most significant environmental laws.”[10] It has also been called “one of the most powerful environmental statutes in the U.S. and one of the world’s strongest species protection laws.”[19]

Continuing need

The available science highlights the need for biodiversity protection laws like the ESA. About one million species worldwide are currently threatened with extinction.[20] North America alone has lost 3 billion birds since 1970.[21] These significant population declines are a precursor to extinction. Half a million species do not have enough habitat for long-term survival. These species are likely to go extinct in the next few decades without habitat restoration.[20] Along with other conservation tools, the ESA is a critical instrument in protecting imperiled species from major ongoing threats. These include climate change, land use change, habitat loss, invasive species, and overexploitation.

Endangered Species Act

President Richard Nixon declared current species conservation efforts to be inadequate and called on the 93rd United States Congress to pass comprehensive endangered species legislation.[22] Congress responded with a completely rewritten law, the Endangered Species Act of 1973, which was signed by Nixon on December 28, 1973 (Pub. L. 93–205). It was written by a team of lawyers and scientists, including Dr. Russell E. Train, the first appointed head of the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), an outgrowth of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969.[23][24] Dr. Train was assisted by a core group of staffers, including Dr. Earl Baysinger at EPA, Dick Gutting, and Dr. Gerard A. "Jerry" Bertrand, a Ph.D marine biologist by training (Oregon State University, 1969), who had transferred from his post as the scientific adviser to the Commandant of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, office of the Commandant of the Corps., to join the newly formed White House office.[citation needed] The staff, under Dr. Train's leadership, incorporated dozens of new principles and ideas into the landmark legislation, crafting a document that completely changed the direction of environmental conservation in the United States.[citation needed]

The stated purpose of the Endangered Species Act is to protect species and also "the ecosystems upon which they depend." California historian Kevin Starr was more emphatic when he said: "The Endangered Species Act of 1972 is the Magna Carta of the environmental movement."[25]

The ESA is administered by two federal agencies, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). NMFS handles marine species, and the FWS has responsibility over freshwater fish and all other species. Species that occur in both habitats (e.g. sea turtles and Atlantic sturgeon) are jointly managed.

In March 2008, The Washington Post reported that documents showed that the Bush Administration, beginning in 2001, had erected "pervasive bureaucratic obstacles" that limited the number of species protected under the act:

- From 2000 to 2003, until a U.S. District Court overturned the decision, Fish and Wildlife Service officials said that if that agency identified a species as a candidate for the list, citizens could not file petitions for that species.

- Interior Department personnel were told they could use "info from files that refutes petitions but not anything that supports" petitions filed to protect species.

- Senior department officials revised a longstanding policy that rated the threat to various species based primarily on their populations within U.S. borders, giving more weight to populations in Canada and Mexico, countries with less extensive regulations than the U.S.

- Officials changed the way species were evaluated under the act by considering where the species currently lived, rather than where they used to exist.

- Senior officials repeatedly dismissed the views of scientific advisers who said that species should be protected.[26]

In 2014, the House of Representatives passed the 21st Century Endangered Species Transparency Act, which would require the government to disclose the data it uses to determine species classification.

In July 2018, lobbyists, Republican legislators, and the administration of President Donald Trump, proposed, introduced, and voted on laws and amendments to the ESA. One example was from the Interior Department which wanted to add economic considerations when deciding if a species should be on the "endangered" or "threatened" list.[27]

In October 2019, at the urging of the Pacific Legal Foundation and the Property and Environment Research Center,[28][29] the USFWS and the NMFS under President Donald Trump changed the §4(d) rule to treat "threatened" and "critically endangered" species differently, legalizing private recovery initiatives and habitats for species that are merely "threatened."[30] Environmental opponents criticized the revision as "crashing like a bulldozer" through the act and "tipping the scales way in favour of industry."[31][32][33] Some critics, including the Sierra Club, have pointed out these changes come just months after the IPBES released its Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, which found that human activity has pushed a million species of flora and fauna to the brink of extinction, and would only serve to exacerbate the crisis.[34][35][36] The California legislature passed a bill to raise California regulations to thwart Trump's changes, but it was vetoed by Governor Newsom.[37] In January 2020, the House Natural Resources Committee reported similar legislation.[38]

Content of the ESA

The ESA consists of 17 sections. Key legal requirements of the ESA include:

- The federal government must determine whether species are endangered or threatened. If so, they must list the species for protection under the ESA (Section 4).

- If determinable, critical habitat must be designated for listed species (Section 4).

- Absent certain limited situations (Section 10), it is illegal to “take” an endangered species (Section 9). “Take” can mean kill, harm, or harass (Section 3).

- Federal agencies will use their authorities to conserve endangered species and threatened species (Section 7).

- Federal agencies cannot jeopardize listed species' existence or destroy critical habitat (Section 7).

- Any import, export, interstate, and foreign commerce of listed species is generally prohibited (Section 9).

- Endangered fish or wildlife cannot be taken without a take permit. This also applies to certain threatened animals with section 4(d) rules (Section 10).

Preventing extinction

The ESA's primary goal is to prevent the extinction of imperiled plant and animal life, and secondly, to recover and maintain those populations by removing or lessening threats to their survival.

Petition and listing

To be considered for listing, the species must meet one of five criteria (section 4(a)(1)):

1. There is the present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range.

2. An over utilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes.

3. The species is declining due to disease or predation.

4. There is an inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms.

5. There are other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence.

Potential candidate species are then prioritized, with "emergency listing" given the highest priority. Species that face a "significant risk to their well being" are in this category.[39]

A species can be listed in two ways. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) or NOAA Fisheries (also called the National Marine Fisheries Service) can directly list a species through its candidate assessment program, or an individual or organizational petition may request that the FWS or NMFS list a species. A "species" under the act can be a true taxonomic species, a subspecies, or in the case of vertebrates, a "distinct population segment." The procedures are the same for both types except with the person/organization petition, there is a 90-day screening period.

During the listing process, economic factors cannot be considered, but must be " based solely on the best scientific and commercial data available."[40] The 1982 amendment to the ESA added the word "solely" to prevent any consideration other than the biological status of the species. Congress rejected President Ronald Reagan's Executive Order 12291 which required economic analysis of all government agency actions. The House committee's statement was "that economic considerations have no relevance to determinations regarding the status of species."[41]

The very opposite result happened with the 1978 amendment where Congress added the words "...taking into consideration the economic impact..." in the provision on critical habitat designation.[42] The 1978 amendment linked the listing procedure with critical habitat designation and economic considerations, which almost completely halted new listings, with almost 2,000 species being withdrawn from consideration.[43]

Listing process

After receiving a petition to list a species, the two federal agencies take the following steps, or rulemaking procedures, with each step being published in the Federal Register, the US government's official journal of proposed or adopted rules and regulations:

1. If a petition presents information that the species may be imperiled, a screening period of 90 days begins (interested persons and/or organization petitions only). If the petition does not present substantial information to support listing, it is denied.

2. If the information is substantial, a status review is started, which is a comprehensive assessment of a species' biological status and threats, with a result of : "warranted", "not warranted," or "warranted but precluded."

- A finding of not warranted, the listing process ends.

- Warranted finding means the agencies publish a 12-month finding (a proposed rule) within one year of the date of the petition, proposing to list the species as threatened or endangered. Comments are solicited from the public, and one or more public hearings may be held. Three expert opinions from appropriate and independent specialists may be included, but this is voluntary.

- A "warranted but precluded" finding is automatically recycled back through the 12-month process indefinitely until a result of either "not warranted" or "warranted" is determined. The agencies monitor the status of any "warranted but precluded" species.[44]

Essentially the "warranted but precluded" finding is a deferral added by the 1982 amendment to the ESA. It means other, higher-priority actions will take precedence.[45] For example, an emergency listing of a rare plant growing in a wetland that is scheduled to be filled in for housing construction would be a "higher-priority".

3. Within another year, a final determination (a final rule) must be made on whether to list the species. The final rule time limit may be extended for 6 months and listings may be grouped together according to similar geography, threats, habitat or taxonomy.

The annual rate of listing (i.e., classifying species as "threatened" or "endangered") increased steadily from the Ford administration (47 listings, 15 per year) through Carter (126 listings, 32 per year), Reagan (255 listings, 32 per year), George H. W. Bush (231 listings, 58 per year), and Clinton (521 listings, 65 per year) before decline to its lowest rate under George W. Bush (60 listings, 8 per year as of 5/24/08).[46]

The rate of listing is strongly correlated with citizen involvement and mandatory timelines: as agency discretion decreases and citizen involvement increases (i.e. filing of petitions and lawsuits) the rate of listing increases.[46] Citizen involvement has been shown to identify species not moving through the process efficiently,[47] and identify more imperiled species.[48] The longer species are listed, the more likely they are to be classified as recovering by the FWS.[49]

Public notice, comments and judicial review

Public notice is given through legal notices in newspapers, and communicated to state and county agencies within the species' area. Foreign nations may also receive notice of a listing. A public hearing is mandatory if any person has requested one within 45 days of the published notice.[50] "The purpose of the notice and comment requirement is to provide for meaningful public participation in the rulemaking process." summarized the Ninth Circuit court in the case of Idaho Farm Bureau Federation v. Babbitt.[51]

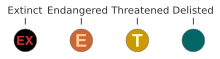

Listing status

Listing status and its abbreviations used in Federal Register and by federal agencies like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service:[52][53][54]

- E = endangered (Sec.3.6, Sec.4.a [52]) – any species which is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range other than a species of the Class Insecta determined by the Secretary to constitute a pest.

- T = threatened (Sec.3.20, Sec.4.a [52]) – any species which is likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range

- Other categories:

- C = candidate (Sec.4.b.3 [52]) – a species under consideration for official listing

- E(S/A), T(S/A) = endangered or threatened due to similarity of appearance (Sec.4.e [52]) – a species not endangered or threatened, but so closely resembles in appearance a species which has been listed as endangered or threatened, that enforcement personnel would have substantial difficulty in attempting to differentiate between the listed and unlisted species.

- XE, XN = experimental essential or non-essential population (Sec.10.j [52]) – any population (including eggs, propagules, or individuals) of an endangered species or a threatened species released outside the current range under authorization of the Secretary. Experimental, nonessential populations of endangered species are treated as threatened species on public land, for consultation purposes, and as species proposed for listing on private land.

Species survival and recovery

Critical habitat

The provision of the law in Section 4 that establishes critical habitat is a regulatory link between habitat protection and recovery goals, requiring the identification and protection of all lands, water and air necessary to recover endangered species.[55] To determine what exactly is critical habitat, the needs of open space for individual and population growth, food, water, light or other nutritional requirements, breeding sites, seed germination and dispersal needs, and lack of disturbances are considered.[56]

As habitat loss is the primary threat to most imperiled species, the Endangered Species Act of 1973 allowed the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) to designate specific areas as protected "critical habitat" zones. In 1978, Congress amended the law to make critical habitat designation a mandatory requirement for all threatened and endangered species.

The amendment also added economics into the process of determining habitat: "...shall designate critical habitat... on the basis of the best scientific data available and after taking into consideration the economic impact, and any other impact, of specifying... area as critical habitat."[42] The congressional report on the 1978 amendment described the conflict between the new Section 4 additions and the rest of the law:

"... the critical habitat provision is a startling section which is wholly inconsistent with the rest of the legislation. It constitutes a loophole which could readily be abused by any Secretary ... who is vulnerable to political pressure or who is not sympathetic to the basic purposes of the Endangered Species Act."-- House of Representatives Report 95-1625, at 69 (1978)[57]

The amendment of 1978 added economic considerations and the 1982 amendment prevented economic considerations.

Several studies on the effect of critical habitat designation on species' recovery rates have been done between 1997 and 2003. Although it has been criticized,[58] the Taylor study in 2003[59] found that, "species with critical habitat were... twice as likely to be improving...."[60]

Critical habitats are required to contain "all areas essential to the conservation" of the imperiled species, and may be on private or public lands. The Fish and Wildlife Service has a policy limiting designation to lands and waters within the U.S. and both federal agencies may exclude essential areas if they determine that economic or other costs exceed the benefit. The ESA is mute about how such costs and benefits are to be determined.

All federal agencies are prohibited from authorizing, funding or carrying out actions that "destroy or adversely modify" critical habitats (Section 7(a) (2)). While the regulatory aspect of critical habitat does not apply directly to private and other non-federal landowners, large-scale development, logging and mining projects on private and state land typically require a federal permit and thus become subject to critical habitat regulations. Outside or in parallel with regulatory processes, critical habitats also focus and encourage voluntary actions such as land purchases, grant making, restoration, and establishment of reserves.[61]

The ESA requires that critical habitat be designated at the time of or within one year of a species being placed on the endangered list. In practice, most designations occur several years after listing.[61] Between 1978 and 1986 the FWS regularly designated critical habitat. In 1986 the Reagan Administration issued a regulation limiting the protective status of critical habitat. As a result, few critical habitats were designated between 1986 and the late 1990s. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a series of court orders invalidated the Reagan regulations and forced the FWS and NMFS to designate several hundred critical habitats, especially in Hawaii, California and other western states. Midwest and Eastern states received less critical habitat, primarily on rivers and coastlines. As of December, 2006, the Reagan regulation has not yet been replaced though its use has been suspended. Nonetheless, the agencies have generally changed course and since about 2005 have tried to designate critical habitat at or near the time of listing.

Most provisions of the ESA revolve around preventing extinction. Critical habitat is one of the few that focus on recovery. Species with critical habitat are twice as likely to be recovering as species without critical habitat.[49]

Plans, permits, and agreements

The combined result of the amendments to the Endangered Species Act have created a law vastly different from the ESA of 1973. It is now a flexible, permitting statute. For example, the law now permits "incidental takes" (accidental killing or harming a listed species). Congress added the requirements for "incidental take statement", and authorized a "incidental take permit" in conjunction with "habitat conservation plans".

More changes were made in the 1990s in an attempt by Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt to shield the ESA from a Congress hostile to the law. He instituted incentive-based strategies such as candidate conservation agreements and "safe harbor" agreements[62] that would balance the goals of economic development and conservation.

Recovery plan

Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) are required to create an Endangered Species Recovery Plan outlining the goals, tasks required, likely costs, and estimated timeline to recover endangered species (i.e., increase their numbers and improve their management to the point where they can be removed from the endangered list).[63] The ESA does not specify when a recovery plan must be completed. The FWS has a policy specifying completion within three years of the species being listed, but the average time to completion is approximately six years.[46] The annual rate of recovery plan completion increased steadily from the Ford administration (4) through Carter (9), Reagan (30), Bush I (44), and Clinton (72), but declined under Bush II (16 per year as of 9/1/06).[46]

The goal of the law is to make itself unnecessary, and recovery plans are a means toward that goal.[64] Recovery plans became more specific after 1988 when Congress added provisions to Section 4(f) of the law that spelled out the minimum contents of a recovery plan. Three types of information must be included:

- A description of "site-specific" management actions to make the plan as explicit as possible.

- The "objective, measurable criteria" to serve as a baseline for judging when and how well a species is recovering.

- An estimate of money and resources needed to achieve the goal of recovery and delisting.[65]

The amendment also added public participation to the process. There is a ranking order, similar to the listing procedures, for recovery plans, with the highest priority being for species most likely to benefit from recovery plans, especially when the threat is from construction, or other developmental or economic activity.[64] Recovery plans cover domestic and migratory species.[66]

Exemptions

Exemptions can and do occur. The ESA requires federal agencies to consult with the US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) or the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) if any project occurs in the habitat of a listed species. An example of such a project might be a timber harvest proposed by the US Forest Service. If the timber harvest could impact a listed species, a biological assessment is prepared by the Forest Service and reviewed by the FWS or NMFS or both.

The question to be answered is whether a listed species will be harmed by the action and, if so, how the harm can be minimized. If harm cannot be avoided, the project agency can seek an exemption from the Endangered Species Committee, an ad hoc panel composed of members from the executive branch and at least one appointee from the state where the project is to occur. Five of the seven committee members must vote for the exemption to allow taking (to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or significant habitat modification,[67] or to attempt to engage in any such conduct) of listed species.[68]

Long before the exemption is considered by the Endangered Species Committee, the Forest Service, and either the FWS or the NMFS will have consulted on the biological implications of the timber harvest. The consultation can be informal, to determine if harm may occur; and then formal if the harm is believed to be likely. The questions to be answered in these consultations are whether the species will be harmed, whether the habitat will be harmed and if the action will aid or hinder the recovery of the listed species.[69]

If harm is likely to occur, the consultation evaluates whether "reasonable and prudent alternatives" exist to minimize harm. If an alternative does not exist, the FWS or NMFS will issue an opinion that the action constitutes "jeopardy" to the listed species either directly or indirectly. The project cannot then occur unless exempted by the Endangered Species Committee.

The Committee must make a decision on the exemption within 30 days, when its findings are published in the Federal Register. The findings can be challenged in federal court. In 1992, one such challenge was the case of Portland Audubon Society v. Endangered Species Committee heard in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.[70]

The court found that three members had been in illegal ex parte contact with the then-President George H.W. Bush, a violation of the Administrative Procedures Act. The committee's exemption was for the Bureau of Land Management's timber sale and "incidental takes" of the endangered northern spotted owl in Oregon.[70]

There have been six instances as of 2009 in which the exemption process was initiated. Of these six, one was granted, one was partially granted, one was denied and three were withdrawn.[71] Donald Baur, in The Endangered Species Act: law, policy, and perspectives, concluded," ... the exemption provision is basically a nonfactor in the administration of the ESA. A major reason, of course, is that so few consultations result in jeopardy opinions, and those that do almost always result in the identification of reasonable and prudent alternatives to avoid jeopardy."[72]

Delisting

To delist species, several factors are considered: the threats are eliminated or controlled, population size and growth, and the stability of habitat quality and quantity. Also, over a dozen species have been delisted due to inaccurate data putting them on the list in the first place.

There is also "downlisting" of a species where some of the threats have been controlled and the population has met recovery objectives, then the species can be reclassified to "threatened" from "endangered"[73]

Two examples of animal species recently delisted are: the Virginia northern flying squirrel (subspecies) on August, 2008, which had been listed since 1985, and the gray wolf (Northern Rocky Mountain DPS). On April 15, 2011, President Obama signed the Department of Defense and Full-Year Appropriations Act of 2011.[74] A section of that Appropriations Act directed the Secretary of the Interior to reissue within 60 days of enactment the final rule published on April 2, 2009, that identified the Northern Rocky Mountain population of gray wolf (Canis lupus) as a distinct population segment (DPS) and to revise the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife by removing most of the gray wolves in the DPS.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service's delisting report lists four plants that have recovered:[75]

-

Eggert's sunflower (Helianthus eggertii)

-

Robbins' cinquefoil (Potentilla robbinsiana), an alpine wildflower found in the White Mountains of New Hampshire

-

Maguire daisy (Erigeron maguirei)

-

Tennessee purple coneflower (Echinacea tennesseensis)

Section 10: Permitting, Conservation Agreements, and Experimental Populations

Section 10 of the ESA provides a permit system that may allow acts prohibited by Section 9. This includes scientific and conservation activities. For example, the government may let someone move a species from one area to another. This would otherwise be a prohibited taking under Section 9. Before the law was amended in 1982, a listed species could be taken only for scientific or research purposes.

Habitat Conservation Plans

Section 10 may also allow activities that can unintentionally impact protected species. A common activity might be construction where these species live. More than half of habitat for listed species is on non-federal property.[76] Under section 10, impacted parties can apply for an incidental take permit (ITP). An application for an ITP requires a Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP).[77] HCPs must minimize and mitigate the impacts of the activity. HCPs can be established to provide protections for both listed and non-listed species. Such non-listed species include species that have been proposed for listing. Hundreds of HCPs have been created. However, the effectiveness of the HCP program remains unknown.[78]

If activities may unintentionally take a protected species, an incidental take permit can be issued. The applicant submits an application with an habitat conservation plan (HCP). If approved by the agency (FWS or NMFS) they are issued an Incidental Take Permit (ITP). The permit allows a certain number of the species to be "taken." The Services have a "No Surprises" policy for HCPs. Once an ITP is granted, the Services cannot require applicants to spend more money or set aside additional land or pay more.[79]

To receive the benefit of the permit the applicant must comply with all the requirements of the HCP. Because the permit is issued by a federal agency to a private party, it is a federal action. Other federal laws will apply such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and Administrative Procedure Act (APA). A notice of the permit application action must be published in the Federal Register and a public comment period of 30 to 90 days offered.[80]

Safe Harbor Agreements

The "Safe Harbor" agreement (SHA) is similar to an HCP. It is voluntary between the private landowner and the Services.[81] The landowner agrees to alter the property to benefit a listed or proposed species. In exchange, the Services will allow some future "takes" through an Enhancement of Survival Permit. A landowner can have either a "Safe Harbor" agreement or an HCP, or both. The policy was developed by the Clinton Administration.[82] Unlike an HCP the activities covered by a SHA are designed to protect species.The policy relies on the "enhancement of survival" provision of Section §1539(a)(1)(A). Safe harbor agreements are subject to public comment rules of the APA.

Candidate Conservation Agreements With Assurances

HCPs and SHAs are applied to listed species. If an activity may "take" a proposed or candidate species, parties can enter into Candidate Conservation Agreements With Assurances (CCAA).[83] A party must show the Services they will take conservation measures to prevent listing. If a CCAA is approved and the species is later listed, the party with a CCAA gets an automatic "enhancement of survival" permit under Section §1539(a)(1)(A). CCAAs are subject to the public comment rules of the APA.

Experimental Populations

Experimental populations are listed species that have been intentionally introduced to a new area. They must be separate geographically from other populations of the same species. Experimental populations can be designated "essential" or "non-essential"[84] "Essential" populations are those whose loss would appreciably reduce the survival of the species in the wild. "Non-essential" populations are all others. Nonessential experimental populations of listed species typically receive less protection than populations in the wild.

Effectiveness

Positive effects

As of January 2019, eighty-five species have been delisted; fifty-four due to recovery, eleven due to extinction, seven due to changes in taxonomic classification practices, six due to discovery of new populations, five due to an error in the listing rule, one due to erroneous data and one due to an amendment to the Endangered Species Act specifically requiring the species delisting.[85] Twenty-five others have been downlisted from "endangered" to "threatened" status.

Some have argued that the recovery of DDT-threatened species such as the bald eagle, brown pelican and peregrine falcon should be attributed to the 1972 ban on DDT by the EPA. rather than the Endangered Species Act. However, the listing of these species as endangered led to many non-DDT oriented actions that were taken under the Endangered Species Act (i.e. captive breeding, habitat protection, and protection from disturbance).

As of January 2019, there are 1,467 total (foreign and domestic)[86] species on the threatened and endangered lists. However, many species have become extinct while on the candidate list or otherwise under consideration for listing.[46]

Species which increased in population size since being placed on the endangered list include:

- Bald eagle (increased from 417 to 11,040 pairs between 1963 and 2007); removed from list 2007

- Whooping crane (increased from 54 to 436 birds between 1967 and 2003)

- Kirtland's warbler (increased from 210 to 1,415 pairs between 1971 and 2005)

- Peregrine falcon (increased from 324 to 1,700 pairs between 1975 and 2000); removed from list 1999

- Gray wolf (populations increased dramatically in the Northern Rockies and Western Great Lakes States)

- Mexican wolf (increased to minimum population of 109 wolves in 2014 in southwest New Mexico and southeast Arizona)

- Red wolf (increased from 17 in 1980 to 257 in 2003)

- Gray whale (increased from 13,095 to 26,635 whales between 1968 and 1998); removed from list (Debated because whaling was banned before the ESA was set in place and that the ESA had nothing to do with the natural population increase since the cease of massive whaling [excluding Native American tribal whaling])

- Grizzly bear (increased from about 271 to over 580 bears in the Yellowstone area between 1975 and 2005)

- California's southern sea otter (increased from 1,789 in 1976 to 2,735 in 2005)

- San Clemente Indian paintbrush (increased from 500 plants in 1979 to more than 3,500 in 1997)

- Florida's Key deer (increased from 200 in 1971 to 750 in 2001)

- Big Bend gambusia (increased from a couple dozen to a population of over 50,000)

- Hawaiian goose (increased from 400 birds in 1980 to 1,275 in 2003)

- Virginia big-eared bat (increased from 3,500 in 1979 to 18,442 in 2004)

- Black-footed ferret (increased from 18 in 1986 to 600 in 2006)

State endangered species lists

Section 6 of the Endangered Species Act[87] provided funding for development of programs for management of threatened and endangered species by state wildlife agencies.[88] Subsequently, lists of endangered and threatened species within their boundaries have been prepared by each state. These state lists often include species which are considered endangered or threatened within a specific state but not within all states, and which therefore are not included on the national list of endangered and threatened species. Examples include Florida,[89] Minnesota,[90] and Maine.[91]

Penalties

There are different degrees of violation with the law. The most punishable offenses are trafficking, and any act of knowingly "taking" (which includes harming, wounding, or killing) an endangered species.

The penalties for these violations can be a maximum fine of up to $50,000 or imprisonment for one year, or both, and civil penalties of up to $25,000 per violation may be assessed. Lists of violations and exact fines are available through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration web-site.[92]

One provision of this law is that no penalty may be imposed if, by a preponderance of the evidence that the act was in self-defense. The law also eliminates criminal penalties for accidentally killing listed species during farming and ranching activities.[93]

In addition to fines or imprisonment, a license, permit, or other agreement issued by a federal agency that authorized an individual to import or export fish, wildlife, or plants may be revoked, suspended or modified. Any federal hunting or fishing permits that were issued to a person who violates the ESA can be canceled or suspended for up to a year.

Use of money received through violations of the ESA

A reward will be paid to any person who furnishes information which leads to an arrest, conviction, or revocation of a license, so long as they are not a local, state, or federal employee in the performance of official duties. The Secretary may also provide reasonable and necessary costs incurred for the care of fish, wildlife, and forest service or plant pending the violation caused by the criminal. If the balance ever exceeds $500,000 the Secretary of the Treasury is required to deposit an amount equal to the excess into the cooperative endangered species conservation fund.

Challenges

Successfully implementing the Act has been challenging in the face of opposition and frequent misinterpretations of the Act’s requirements. One challenge attributed to the Act, though debated often, is the cost conferred on industry. These costs may come in the form of lost opportunity or slowing down operations to comply with the regulations put forth in the Act. Costs tend to be concentrated in a handful of industries. For example, the requirement to consult with the Services on federal projects has at times slowed down operations by the oil and gas industry. The industry has often pushed to develop millions of federal acres of land rich in fossil fuels. Some argue the ESA may encourage preemptive habitat destruction or taking listed or proposed species by landowners.[94] One example of such perverse incentives is the case of a forest owner who, in response to ESA listing of the red-cockaded woodpecker, increased harvesting and shortened the age at which he harvests his trees to ensure that they do not become old enough to become suitable habitat.[95] Some economists believe that finding a way to reduce such perverse incentives would lead to more effective protection of endangered species.[96] According to research published in 1999 by Alan Green and the Center for Public Integrity (CPI) there are also loopholes in the ESA are commonly exploited in the exotic pet trade. These loopholes allow some trade in threatened or endangered species within and between states.[97]

As a result of these tensions, the ESA is often seen as pitting the interests of conservationists and species against industry. One prominent case in the 1990’s involved the proposed listing of Northern spotted owl and designation of critical habitat. Another notable case illustrating this contentiousness is the protracted dispute over the Greater sage grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus).

Extinctions and species at risk

Critics of the Act have noted that despite its goal of recovering species so they are no longer listed, this has rarely happened. In its almost 50 year history, less than fifty species have been delisted due to recovery.[98] Indeed, since the passage of the ESA, several species that were listed have gone extinct. Many more that are still listed are at risk of extinction. This is true despite conservation measures mandated by the Act. As of January 2020 the Services indicate that eleven species have been lost to extinction. These extinct species are the Caribbean monk seal, the Santa Barbara song sparrow; the Dusky seaside sparrow; the Longjaw cisco; the Tecopa pupfish; the Guam broadbill; the astern puma; and the Blue pike.

The National Marine Fisheries Service lists eight species among the most at risk of extinction in the near future. These species are the Atlantic salmon; the Central California Coast coho; the Cook Inlet beluga whale; the Hawaaian monk seal; the Pacific leatherback sea turtle; the Sacramento River winter-run chinook salmon; the Southern resident killer whale; and last, the White abalone. Threats from human activities are the primary cause for most being threatened. The Services have also changed a species’ status from threatened to endangered on nine occasions. Such a move indicates that the species is closer to extinction. However, the number of status changes from endangered to threatened is greater than vice versa.[99]

However, defenders of the Act have argued such criticisms are unfounded. For example, many listed species are recovering at the rate specified by their recovery plan.[100] Research shows that the vast majority of listed species are still extant[101] and hundreds are on the path to recovery.[102]

Species awaiting listing

A 2019 report found that FWS faces a backlog of more than 500 species that have been determined to potentially warrant protection. All of these species still await a decision. Decisions to list or defer listing for species are supposed to take 2 years. However on average it has taken the Fish and Wildlife Service 12 years to finalize a decision.[103] A 2016 analysis found that approximately 50 species may have gone extinct while awaiting a listing decision.[102] More funding might let the Services direct more resources towards biological assessments of these species and determine if they merit a listing decision.[104] An additional issue is that species still listed under the Act may already be extinct. For example, the IUCN Red List declared the Scioto madtom extinct in 2013. It had last been seen alive in 1957.[105] However, FWS still classifies the catfish as endangered.[106]

Misconceptions and misinformation

Certain misconceptions about the ESA and its tenants have become widespread. These misconceptions have served to increase backlash against the Act.[107] One widely-held opinion is that the protections afforded to listed species curtail economic activity.[108] Legislators have expressed that the ESA has been “weaponized,” particularly against western states, preventing these states from utilizing these lands.[109]

However, given that the standard to prevent jeopardy or adverse modification applies only to federal activities, this claim is often misguided. One analysis looked at 88,290 consultations from 2008 to 2015. The analysis found that not a single project was stopped as a result of potential adverse modification or jeopardy.[110]

Another misguided belief is that critical habitat designation is akin to establishment of a wilderness area or wildlife refuge. As such, many believe that the designation closes the area to most human uses.[111] In actuality, a critical habitat designation solely affects federal agencies. It serves to alert these agencies that their responsibilities under section 7 are applicable in the critical habitat area. Designation of critical habitat does not affect land ownership; allow the government to take or manage private property; establish a refuge, reserve, preserve, or other conservation area; or allow government access to private land.[112]

See also

- Critical habitat

- Endangered Species Act Amendments of 1978

- List of endangered species in North America

- Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill

- Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife

- Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Footnotes

- ^ a b "Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill", 437 U.S. 153 (1978) Retrieved 24 November 2015.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Government.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Government.

- ^ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. "International Affairs: CITES" Retrieved on 29 January 2020.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.

- ^ Summary of the Endangered Species Act | Laws & Regulations | US EPA

- ^ Dunlap, Thomas R. (1988). Saving America's wildlife. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04750-2. OCLC 16833470.

- ^ "Whooping Crane: Natural History Notebooks". nature.ca. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ Punke, Michael. (2007). Last stand : George Bird Grinnell, the battle to save the buffalo, and the birth of the new West (1st Smithsonian books ed.). New York: Smithsonian Books/Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-089782-6. OCLC 78072713.

- ^ "Lacey Act". www.fws.gov. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ "Whooping Crane | National Geographic". Animals. November 11, 2010. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ "Bald Eagle Fact Sheet". www.fws.gov. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ a b Bean, Michael J. (April 2009). "The Endangered Species Act: Science, Policy, and Politics". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1162 (1): 369–391. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04150.x. PMID 19432657.

- ^ "PUBLIC LAW 89-669-OCT. 15, 1966" (PDF).

((cite web)): CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Goble, Endangered Species Act at Thirty p. 45

- ^ AP (March 12, 1967). "78 Species Listed Near Extinction; Udall Issues Inventory With Appeal to Save Them". New York Times.

- ^ "The Role of the Endangered Species Act and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in the Recovery of the Peregrine Falcon". www.fws.gov. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ "Public Law 91-135-Dec. 5, 1969" (PDF).

((cite web)): CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "GA 1963 RES 005 | IUCN Library System". portals.iucn.org. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ "What is CITES? | CITES". www.cites.org. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ "Endangered Species Program | Laws & Policies | Endangered Species Act | A History of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 | The Endangered Species Act at 35". www.fws.gov. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ "Inside the Effort to Kill Protections for Endangered Animals". National Geographic News. August 12, 2019. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ a b Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) (2019). Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. IPBES. OCLC 1135470693.

((cite book)):|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Rosenberg, Kenneth V.; Dokter, Adriaan M.; Blancher, Peter J.; Sauer, John R.; Smith, Adam C.; Smith, Paul A.; Stanton, Jessica C.; Panjabi, Arvind; Helft, Laura; Parr, Michael; Marra, Peter P. (October 4, 2019). "Decline of the North American avifauna". Science. 366 (6461): 120–124. doi:10.1126/science.aaw1313. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Nixon. R (1972). "Special Message to the Congress Outlining the 1972 Environmental Program".

- ^ "Environmental Protection Agency". Archived from the original on February 3, 2011.

- ^ Rinde, Meir (2017). "Richard Nixon and the Rise of American Environmentalism". Distillations. 3 (1): 16–29. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ Water on the Edge KVIE-Sacramento public television documentary (DVD) hosted by Lisa McRae. The Water Education Foundation, 2005

- ^ Juliet Eilperin, "Since '01, Guarding Species Is Harder: Endangered Listings Drop Under Bush", Washington Post, March 23, 2008

- ^ "Here's Why the Endangered Species Act Was Created in the First Place". Time. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- ^ "Interior announces improvements to the Endangered Species Act". Pacific Legal Foundation. March 23, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- ^ "The Road to Recovery". PERC. April 24, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- ^ "USFWS and NMFS Approve Changes to Implementation of Endangered Species Act". Civil & Environmental Consultants, Inc. October 16, 2019. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- ^ "Trump to roll back endangered species protections". August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- ^ Lambert, Jonathan (August 12, 2019). "Trump administration weakens Endangered Species Act". Nature. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ D’Angelo, Chris (August 12, 2019). "Trump Administration Weakens Endangered Species Act Amid Global Extinction Crisis". The Huffington Post. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ Resnick, Brian (August 12, 2019). "The Endangered Species Act is incredibly popular and effective. Trump is weakening it anyway". Vox. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ "Colorful Tennessee fish protected as endangered". Phys.org. October 21, 2019. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ "Trump Extinction Plan Guts Endangered Species Act". Sierra Club. August 12, 2019. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ "Newsom signals he is rejecting far-reaching environmental legislation". CalMatters. September 15, 2019. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- ^ "House panel OKs bill to undo Trump changes to Endangered Species Act". Cronkite News. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- ^ "Notice". Endangered and Threatened Wildlife; Final Listing Priority Guidance for FY 2000. Federal Register. pp. 27114–19. Retrieved July 3, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ 16 U.S.C. §1533(b)(1)(A)

- ^ Stanford, p. 40

- ^ a b 16 U.S.C. 1533(b)(2)

- ^ Stanford p. 23

- ^ 16 U.S.C. 1533 (b)(3)(C)(iii)

- ^ ESA at Thirty p. 58

- ^ a b c d e Greenwald, Noah; K. Suckling; M. Taylor (2006). "Factors affecting the rate and taxonomy of species listings under the U.S. Endangered Species Act". In D. D. Goble; J.M. Scott; F.W. Davis (eds.). The Endangered Species Act at 30: Vol. 1: Renewing the Conservation Promise. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. pp. 50–67. ISBN 1597260096.

- ^ Puckett, Emily E.; Kesler, Dylan C.; Greenwald, D. Noah (2016). "Taxa, petitioning agency, and lawsuits affect time spent awaiting listing under the US Endangered Species Act". Biological Conservation. 201: 220–229. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.07.005.

- ^ Brosi, Berry J.; Biber, Eric G. N. (2012). "Citizen Involvement in the U.S. Endangered Species Act". Science. 337 (6096): 802–803. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..802B. doi:10.1126/science.1220660. PMID 22903999.

- ^ a b Taylor, M. T.; K. S. Suckling; R. R. Rachlinski (2005). "The effectiveness of the Endangered Species Act: A quantitative analysis". BioScience. 55 (4): 360–367. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2005)055[0360:TEOTES]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0006-3568.

((cite journal)): Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ U.S.C 1533(b)(5)(A)-(E)

- ^ Stanford p. 50

- ^ a b c d e f "ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT OF 1973" (PDF). U.S. Senate Committee on Environment & Public Works. Retrieved December 25, 2012.

- ^ "Endangered Species Program – Species Status Codes". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved December 25, 2012.

- ^ "Electronic Code of Federal Regulations, Title 50: Wildlife and Fisheries". U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved December 25, 2012.

- ^ ESA at Thirty p. 89

- ^ Stanford pp. 61–4

- ^ Stanford p. 68

- ^ "U.S. Endangered Species Act Works, Study Finds".

- ^ Center for Biological Diversity, authors K.F. Suckling, J.R. Rachlinski

- ^ Stanford p. 86

- ^ a b Suckling, Kieran; M. Taylor (2006). "Critical Habitat Recovery". In D.D. Goble; J.M. Scott; F.W. Davis (eds.). The Endangered Species Act at 30: Vol. 1: Renewing the Conservation Promise. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. p. 77. ISBN 1597260096.

- ^ ESA at 30, p. 10

- ^ The ESA does allow FWS and NMFS to forgo a recovery plan by declaring it will not benefit the species, but this provision has rarely been invoked. It was most famously used to deny a recovery plan to the northern spotted owl in 1991, but in 2006 the FWS changed course and announced it would complete a plan for the species.

- ^ a b 16 U.S.C. §1533(f)

- ^ Stanford pp. 72–3

- ^ Stanford, p. 198

- ^ "Endangered Species Act". US Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ 16 U.S.C. §1536(e)

- ^ 50 C.F.R. §402.13(a)

- ^ a b "Portland Audubon Society v. Endangered Species Committee". Justia. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Earth accessed August 21, 2009

- ^ Donald C. Baur, William Robert Irvin The Endangered Species Act: law, policy, and perspectives Published by American Bar Association. 2002

- ^ USFWS "Delisting a Species" accessed August 25, 2009 Archived March 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Federal Register, Volume 76 Issue 87 (Thursday, May 5, 2011)".

- ^ FWS Delisting Report Archived 2007-07-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Stanford p. 127

- ^ "Endangered Species | What We Do | Habitat Conservation Plans | Overview". www.fws.gov. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ "Why Isn't Publicly Funded Conservation on Private Land More Accountable?". Yale E360. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ Stanford pp. 170–1

- ^ Stanford pp. 147–8

- ^ "Endangered Species | For Landowners | Safe Harbor Agreements". www.fws.gov. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ Stanford pp168–9

- ^ "Endangered Species Program | What We Do | Candidate Conservation | Candidate Conservation Agreements with Assurances Policy". www.fws.gov. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ "Non-Essential Experimental Population". Southeast Region of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ United States Fish and Wildlife Service Threatened and Endangered Species System

- ^ Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife. "Listed Species Summary (Boxscore)". Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ "16 U.S. Code § 1535 - Cooperation with States".

- ^ 16 U.S. Code 1535

- ^ Florida Endangered & Threatened Species List

- ^ Minnesota Endangered & Threatened Species List

- ^ Compare: Maine State & Federal Endangered & Threatened Species Lists Archived 2008-12-07 at the Wayback Machine with Maine Animals

- ^ http://www.gc.noaa.gov/schedules/6-ESA/EnadangeredSpeciesAct.pdf

- ^ [1] Archived April 6, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Stephen Dubner and Steven Levitt, Unintended Consequences, New York Times Magazine, 20 January 2008

- ^ Richard L. Stroup. [2] Archived October 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, The Endangered Species Act: Making Innocent Species the Enemy PERC Policy Series: April 1995

- ^ Brown, Gardner M. Jr.; Shogren, Jason F. (1998). "Economics of the Endangered Species Act". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 12 (3): 3–20. doi:10.1257/jep.12.3.3.

- ^ Green & The Center for Public Integrity 1999, pp. 115 & 120.

- ^ "Species Search". ecos.fws.gov. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ "Reclassified Species". ecos.fws.gov. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ "110 Success Stories for Endangered Species Day 2012". www.esasuccess.org. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ Greenwald, Noah; Suckling, Kieran F.; Hartl, Brett; Mehrhoff, Loyal A. (April 22, 2019). "Extinction and the U.S. Endangered Species Act". PeerJ. 7: e6803. doi:10.7717/peerj.6803. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 6482936. PMID 31065461.

((cite journal)): CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Evans, Daniel; et al. "Species Recovery in the United States: Increasing the Effectiveness of the Endangered Species Act" (PDF). Issues in Ecology.

- ^ Puckett, Emily E.; Kesler, Dylan C.; Greenwald, D. Noah (September 2016). "Taxa, petitioning agency, and lawsuits affect time spent awaiting listing under the US Endangered Species Act". Biological Conservation. 201: 220–229. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.07.005.

- ^ "Infographic: The ESA needs more than double its current funding" (PDF). Center for Conservation Innovation, Defenders of Wildlife.

((cite web)): CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Platt, John R. "Tiny Ohio Catfish Species, Last Seen in 1957, Declared Extinct". Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ "The endangered species list is full of ghosts". Popular Science. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ Richard L. Stroup. [3] Archived October 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, The Endangered Species Act: Making Innocent Species the Enemy PERC Policy Series: April 1995

- ^ Blackmon, David. "The Radical Abuse of the ESA Threatens the US Economy". Forbes. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ "Western Caucus Introduces Bipartisan Package Of Bills Aimed To Reform, Update ESA". Western Wire. July 12, 2018. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ Malcom, Jacob W.; Li, Ya-Wei (December 29, 2015). "Data contradict common perceptions about a controversial provision of the US Endangered Species Act". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (52): 15844–15849. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11215844M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1516938112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4702972. PMID 26668392.

- ^ "Department of the Interior News Release" (PDF). November 12, 1976.

((cite web)): CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Critical Habitat under the Endangered Species Act". Southeast Region of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

References

- Corn, M. Lynne and Alexandra M. Wyatt. The Endangered Species Act: A Primer. Congressional Research Service 2016.

- The Endangered Species Act at Thirty Dale Goble, J. Michael Scott (editors) Island Press 2006.

- Green, Alan; The Center for Public Integrity (1999). Animal Underworld: Inside America's Black Market for Rare and Exotic Species. Public Affairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-374-6.

((cite book)): Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stanford Environmental Law Society, The Endangered Species Act Stanford University Press 2001 ISBN 0-8047-3842-4.

External links

- ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT OF 1973 accessed November 11, 2011

- Cornell University Law School-Babbit v. Sweet Home accessed July 25, 2005 The 1995 decision on whether significant habitat modifications on private property that actually kill species constitute "harm" for purposes of the ESA.

- Center for Biological Diversity accessed July 25, 2005

- Endangered Species Program – US Fish & Wildlife Service accessed June 16, 2012

- Endangered Species Act – National Marine Fisheries Service – NOAA accessed June 16, 2012

- Species Status Categories and Codes – US Fish & Wildlife Service accessed June 16, 2012

- Habitat Conservation Plans – US Fish & Wildlife Service accessed June 16, 2012

- The 1978 decision related to the ESA and the snail darter. accessed July, 2005

- Summary of Listed Species Listed Populations and Recovery Plans – US Fish & Wildlife Service accessed June 16, 2012

- Species Search – US Fish & Wildlife Service accessed June 16, 2012

- Electronic Code of Federal Regulations: List of endangered species accessed June 16, 2012

| |||||||||||

| Life and politics | |||||||||||

| Books | |||||||||||

| Elections |

| ||||||||||

| Popular culture |

| ||||||||||

| Related | |||||||||||

| Staff |

| ||||||||||

| Family |

| ||||||||||