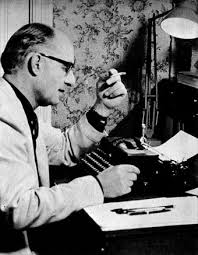

British poet and writer (1911-1966)

Henry Treece (22 December 1911 – 10 June 1966) was a British poet and writer who also worked as a teacher and editor. He wrote a range of works but is mostly remembered as a writer of children's historical novels.[1]

Life and work

Treece was born in Wednesbury, Staffordshire, and educated at the town's grammar school. After graduating from the University of Birmingham in 1933, he went into teaching with his first placement being at Tynemouth School. In 1939 he married Mary Woodman and settled in Lincolnshire as a teacher at Barton-upon-Humber Grammar School.[2] Their son, Richard Treece, became a musician with Help Yourself and other rock bands.[3]

He published five volumes of poetry: 38 Poems (London: Fortune Press, 1940), then by Faber & Faber; Invitation and Warning 1942; The Black Seasons 1945; The Haunted Garden 1947; and The Exiles 1952. He appeared in the 1949 The New British Poets: an anthology edited by Kenneth Rexroth; but from 1952 with The Dark Island he devoted himself to fiction. His best known are his juvenile historical novels, particularly those set in the Viking Age, although he also wrote some adult historical novels. Many of his novels are set in transitional periods in history, where more primitive societies are forced to face modernisation, e.g. the end of the Viking period, or the Roman conquest of Britain. His play Carnival King (Faber & Faber) was produced at Nottingham Playhouse in 1953. He also worked as a radio broadcaster.

[4]

In World War II he served as an intelligence officer in the RAF and helped John Pudney edit Air Force Poetry.[5]

Other poetry anthologies he was involved with include The New Apocalypse (1939) with J. F. Hendry giving its name to the New Apocalyptics movement; two further anthologies with Hendry followed. He wrote a critical study of Dylan Thomas, called Dylan Thomas – Dog among the fairies, published by Lindsay Drummond, London, in 1949. He and Thomas became estranged over Thomas's refusal to sign up as a New Apocalyptic.[6]

He also wrote Conquerors in 1932, as a way to reflect on the horrors of war.[7]

He edited issues of the magazines Transformation, and A New Romantic Anthology (1949) with Stefan Schimanski, issues of Kingdom Come: The Magazine of War-Time Oxford with Schimanski and Alan Rook, as well as War-Time Harvest. How I See Apocalypse (London, Lindsay Drummond, 1946) was a retrospective statement. Treece died from a heart attack in 1966.[8]

Treece's residency in Barton-upon-Humber is recorded by a blue plaque on East Acridge House, erected by the Civic Society in 2010.[9]