History of foreign relations of China covers diplomatic, military, political and economic relations of History of China China from 1800 to 1991. For the earlier period see Foreign relations of China, and for the most recent period see Foreign relations of China.

Qing Dynasty

By the mid 19th century, Chinese stability had come under increasing threat from both domestic and international sources. Social unrest and serious revolts became more common while the regular army had Was too weak to deal with foreign military forces. Chinese leaders increasingly feared the impact of Western ideas. John Fairbank argues that in 1840 to 1895 China's response to the worsening relations with Western nations came in four phases. China's military weakness was interpreted in the 1840s and 1850s as a need for Western arms. Very little was achieved in this regard until much later. In the 1860s there was a focus on acquiring Western technology-- as Japan was doing very successfully at the same time, but China lagged far behind. The 1870s to 1890s were characterized with efforts to reform and revitalize the Chinese political system more broadly. There was steady moderate progress, but efforts to leap forward such as the Hundred Days' Reform in 1898 roused the conservatives who stamped out the effort and executed its leaders. There was a rise in Chinese nationalism, as a sort of echo of Western nationalism, but that led to a quick defeat in war with Japan in 1895. An intense reaction against modernization set in at the grassroots level in the Boxer Rebellion of 1900.[1]

Opium Wars

European commercial interests sought to end the trading barriers, but China fended off repeated efforts by Britain to reform the trading system. Increasing sales of Indian opium to China by British traders led to the First Opium War (1839–1842). The superiority of Western militaries and military technology like steamboats and Congreve rockets forced China to open trade with the West on Western terms.[2]

The Second Opium War also known as the Arrow War, in 1856-60 saw a joint Anglo-French military mission including Great Britain and the French Empire win an easy victory. The agreements of the Convention of Peking led to the ceding of Kowloon Peninsula as part of Hong Kong.[3]

Unequal treaties

A series of "unequal treaties", including the Treaty of Nanking (1842), the treaties of Tianjin (1858), and the Beijing Conventions (1860), forced China to open new treaty ports, including Canton (Guangzhou), Amoy (Xiamen), and Shanghai. The treaties also allowed the British to set up Hong Kong as a colony and established international settlements in the treaty ports under the control of foreign diplomats. China was required to accept diplomats at the capital in Peking, provided for the free movement for foreign ships in Chinese rivers, kept its tariffs low, and opened the interior to Christian missionaries. Manchu leaders of the Qing government found the treaties useful, because they forced the foreigners into a few limited areas, so that the vast majority of Chinese had no contact whatsoever with them or their dangerous ideas. The missionaries, however, ventured more widely but they were widely distrusted and made very few converts. Their main impact was setting up schools and hospitals.[4] Since the 1920s, the "unequal treaties" have been a centerpiece of angry Chinese grievances against the West in general.[5]

Suzerain and tributaries

For centuries China had claimed suzerain authority over numerous adjacent areas. The areas had internal autonomy but were forced to give tribute to China while being theoretically under the protection of China in terms of foreign affairs. By the 19th century the relationships were nominal, and China exerted little or no actual control.[6] The great powers did not recognize China's fiefdom and one by one seized the supposed suzerain areas. Japan moved to dominate Korea (and annexed it in 1910)[7] and seized the Ryukyus;[8] France took Vietnam;[9] Britain took Burma[10] and Nepal; Russia took parts of Siberia. Only Tibet was left, and that was highly problematic since the Tibetans, as most of the supposed suzerainty, had never accepted Chinese claims of lordship and tribute.[11] The losses humiliated China and marked it as a repeated failure.

Christian missionaries

Beginning in Protestant missionaries Began coming, eventually to include thousands of men, their wives and children, and unmarried female missionaries. These were not individual operations, they were sponsored and financed by organized churches in their home country. The 19th century is one of steady geographical expansion, which was reluctantly allowed by the Chinese government every time it lost a war. At first they were limited to the Canton area. In the 1842 treaty ending the First Opium War missionaries were granted the right to live and work in five coastal cities. In 1860, the treaties ending the Second Opium War opened up the entire country to missionary activity. Protestant missionary activity exploded during the next few decades. From 50 missionaries in China in 1860, the number grew to 2,500 (counting wives and children) in 1900. 1,400 of the missionaries were British, 1,000 were Americans, and 100 were from continental Europe, mostly Scandinavia.[12] Protestant missionary activity peaked in the 1920s and thereafter declined due to war and unrest in China, As well as a sense of frustration among the missionaries themselves. By 1953, all Protestant missionaries had been expelled by the communist government of China

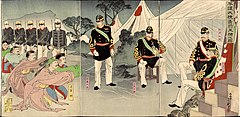

First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895)

A weakened China lost wars with Japan and gave up nominal control over the Ryukyu Islands in 1870 to Japan. After the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894 it lost Formosa to Japan. After the Sino-French War of 1884-1885, France took control of Vietnam, another supposed "tributary state." After Britain took over Burma, as a show of good faith they maintained the sending of tribute to China, putting themselves in a lower status than in their previous relations.[13] To affirm this, Britain agreed in the Burma convention in 1886 to continue the Burmese payments to China every 10 years, in return for which China would recognise Britain's occupation of Upper Burma.[14]

Japan after 1860 modernized its military after Western models and was far stronger than China. The war, fought in 1894 and 1895, was fought to resolve the issue of control over Korea, which was yet another suzerain claimed by China and under the rule of the Joseon Dynasty. A peasant rebellion led to a request by the Korean government for China to send in troops to stabilize the country. The Empire of Japan responded by sending its own force to Korea and installing a puppet government in Seoul. China objected and war ensued. It was a brief affair, with Japanese ground troops routing Chinese forces on the Liaodong Peninsula and nearly destroying the Chinese navy in the Battle of the Yalu River.[15] China, badly defeated, sued for peace and was forced to accept the harsh Treaty of Shimonoseki Signed on April 17, 1895.[16] China became responsible for an enormous financial indemnity, and surrender the island of Taiwan, and the Pescatore Islands. It permitted Japan to set up industries and for treaty ports, gave it the most favored nation status that the Westerners enjoyed, and recognize the independence of Korea. The most controversial provision ceded the Liaodong Peninsula to Japan. However, However this was not acceptable to Russia, Germany, and France. They unexpectedly intervened and . forced Japan to withdraw from Liaodong Peninsula. [17] To pay the indemnities, British French and Russian banks loaned China the money, but also gained other advantages. Russia in 1896 was given permission to extend its Trans-Siberian Railway across Manchuria to reach flat of last stock, a 350 mile shortcut. The , the Chinese Eastern Railway, was controlled by the Russians, and became a major military factor for them. Later in 1896 Russia and China made a secret alliance, whereby Russia would work to prevent further Japanese expansion at China's expense. In 1898 Rush obtained a 25 year lease over the Liadong Peninsula in southern Manchuria, including the ice free harbor of Port Arthur, their only such facility in the East. An extension of the Chinese Eastern Railway to Port Arthur greatly expanded Russian military capabilities in the Far East. [18]

Reforms in 1890s

One of the governments's main source of income was a five percent tariff on imports. The government hired Robert Hart (1835-1911), a British diplomat to run it from 1863. He set up an efficient system based in Canton that was largely free of corruption, and expanded it to other ports. The top echelon of the service was recruited from all the nations trading with China. Hart promoted numerous modernising programs.[19] His agency established a modern postal service and supervision of internal taxes on trade. Hart helped establish its own embassies in foreign countries. He helped set up the Tongwen Guan (School of Combined Learning) in Peking, with a branch in Canton, to teach foreign languages, culture and science. In 1902 the Tongwen Guan was absorbed into the Imperial University, now Peking University.[20][21]

Hundred Days Reform fails in 1898

The Hundred Days Reform was a failed 103-day national, cultural, political, and educational reform movement from 11 June to 22 September 1898. It was undertaken by the young Guangxu Emperor and his reform-minded supporters. Following the issuing of over 100 reformative edicts, a coup d'état ("The Coup of 1898", Wuxu Coup) was perpetrated by powerful conservative opponents led by Empress Dowager Cixi. The Emperor was locked up until his death and key reformers were exiled or fled.[22][23]

Boxer rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion (1897–1901) was an anti-foreigner movement by the Righteous Harmony Society in China between 1897 and 1901 after a massive increase in imperialist activities and concession seizing by foreign powers. The militaries of the nationalists were ludicrously out of date and lacked the support of the Chinese military. The uprising ended with an Alliance of Eastern and Western nations known as the Eight Nation Alliance emerging victorious.[24] On top of all the damage and pillage, China was forced to pay a large annual cash indemnity to all the victors--it ended in 1949. Robert Hart, the inspector general of the Imperial Maritime Customs Service, was the chief negotiator for the peace terms. The indemnity, despite some beneficial programs, was "nothing but bad" for China, as Hart had predicted at the beginning of the negotiations.[25]

Manchuria

Manchuria was a contested zone with Russia and Japan taking control away from China and in the process going to war themselves in 1904-1905.[26]

Republican China =

Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908) was in control of imperial policy from after 1861; she had remarkable political skills but historians generally blame her for major policy failures and the growing weakness of China. Her reversal of reforms in 1898 and especially support for the Boxers caused all the powers to join against her. Late Qing China remains a symbol of national humiliation and weakness in Chinese and international historiography. Scholars attribute Cixi's "rule behind the curtains" responsible for the ultimate decline of the Qing dynasty and its capitulatory peace with foreign powers. Her failures hastened the revolution to overthrow the dynasty.[27]

The Republican Revolution of 1911 overthrew the imperial court and brought an era of regional warlords. In terms of foreign policy the new government tried with limited success to renegotiate the unequal treaties. In 1931, Japan seized control of Manchuria over the objections of the League of Nations. Japan quit the League, which was helpless.[28] The most active Chinese diplomat was Wellington Koo.[29]

War with Japan: 1937–1945

Japan invaded in 1937, launching the Second Sino-Japanese War. By 1938, the United States was a strong supporter of China. Michael Schaller says that during 1938:

- China emerged as something of a symbol of American-sponsored resistance to Japanese aggression.... A new policy appeared, one predicated on the maintenance of a pro-American China which might be a bulwark against Japan. The United States hoped to use China as the weapon with which to contain Tokyo's larger imperialism. Economic assistance, Washington hoped, could achieve this result.[30]

Even the isolationists who opposed war in Europe supported a hard-line against Japan. American public sympathy for the Chinese, and hatred of Japan, was aroused by reports from missionaries, novelists such as Pearl Buck, and Time Magazine of Japanese brutality in China, including reports surrounding the Nanjing Massacre, called the 'Rape of Nanking'. By early 1941, the U.S. was preparing to send American planes flown by American pilots under American command, but wearing Chinese uniforms, to fight the Japanese invaders and even to bomb Japanese cities. There were delays and the "Flying Tigers" under Claire Lee Chennault finally became operational days after Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941) brought the U.S. into the war officially. The Flying Tigers were soon incorporated into the United States Air Force, which made operations in China a high priority, and generated enormous favorable publicity for the China in the U.S.[31]

After Japan took Southeast Asia, American aid had to be routed through India and over the Himalayan Mountains at enormous expense and frustrating delay. Chiang's beleaguered government was now headquartered in remote Chongqing. Roosevelt sent Joseph Stilwell to train Chinese troops and coordinate military strategy. He became the Chief of Staff to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, served as U.S. commander in the China Burma India Theater, was responsible for all Lend-Lease supplies going to China, and was later Deputy Commander of South East Asia Command. Despite his status and position in China, he became involved in conflicts with other senior Allied officers, over the distribution of Lend-Lease materiel, Chinese political sectarianism and proposals to incorporate Chinese and U.S. forces in the 11th Army Group (which was under British command).[32] Madame Chiang Kaishek, who had been educated in the U.S., addressed the U.S. Congress and toured the country to rally support for China.[33] Congress amended the Chinese Exclusion Act and Roosevelt moved to end the unequal treaties. Chiang and Mme. Chiang met with Roosevelt and Churchill at the Cairo Conference of late 1943, but promises of major increases in aid did not materialize.[34]

The perception grew that Chiang's government, with poorly equipped and ill-fed troops was unable to effectively fight the Japanese or that he preferred to focus more on defeating the Communists. China Hands advising Stilwell argued that it was in American interest to establish communication with the Communists to prepare for a land-based counteroffensive invasion of Japan. The Dixie Mission, which began in 1943, was the first official American contact with the Communists. Other Americans, led by Chennault, argued for air power. In 1944, Generalissimo Chiang acceded to Roosevelt's request that an American general take charge of all forces in the area, but demanded that Stilwell be recalled. General Albert Coady Wedemeyer replaced Stilwell, Patrick J. Hurley became ambassador, and Chinese-American relations became much smoother. The U.S. had included China in top-level diplomacy in the hope that large masses of Chinese troops would defeat Japan with minimal American casualties. When that hope was seen as illusory, and it was clear that B-29 bombers could not operate effectively from China, China became much less important to Washington, but it was promised a seat in the new UN Security Council, with a veto.[35]

Civil War

When civil war threatened, President Harry Truman sent General George Marshall to China at the end of 1945 to broker a compromise between the Nationalist government and the Communists, who had established control in much of northern China. Marshall hoped for a coalition government, and brought the two distrustful sides together. At home, many Americans saw China as a bulwark against the spread of communism, but some Americans hoped that the Communists would remain on friendly terms with the U.S.[36] Mao had long admired the U.S.—George Washington was a hero to him—and saw it as an ally in the Second World War. He was bitterly disappointed when the U.S. would not abandon the Nationalists, writing that "the imperialists who had always been hostile to the Chinese people will not change overnight to treat us on an equal level." His official policy was "wiping out the control of the imperialists in China completely."[37] Truman and Marshall, while supplying military aid and advice, determined that American intervention could not save the Nationalist cause. One recent scholar argues that the Communists won the Civil War because Mao Zedong made fewer military mistakes and Chiang Kai-shek antagonized key interest groups. Furthermore, his armies had been weakened in the war against Japanese. Meanwhile the Communists promised to improve the ways of life for groups such as farmers.[38]

Stalin's policy was opportunistic and utilitarian. He offered official Soviet support only when the People's Liberation Army had virtually won the Civil War. Sergey Radchenko argues that "all the talk of proletarian internationalism in the Sino-Soviet alliance was but a cloak for Soviet expansionist ambitions in East Asia". [39]

People's Republic of China

International recognition of the People's Republic of China

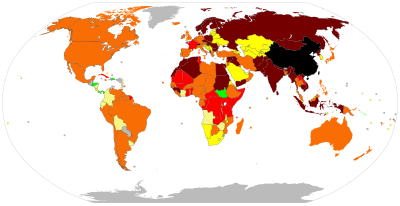

Since its establishment in 1949, the People's Republic of China has worked vigorously to win international recognition and support for its position that it is the sole legitimate government of all China, including Hong Kong (Foreign relations of Hong Kong), Macau (Foreign relations of Macau), Taiwan (Foreign relations of Taiwan), the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands and islands in the South China Sea.

Upon its establishment in 1949, the People's Republic of China was recognized by Eastern Bloc countries. Among the first Western countries to recognize China were the United Kingdom (on 6 January 1950), Switzerland (on 17 January 1950[40]) and Sweden (on 14 February 1950[41]). The first Western country to establish diplomatic ties with China was Sweden (on 9 May 1950).[42][43] Until the early 1970s, the Republic of China government in Taipei was recognized diplomatically by most world powers and held the seat in the UN Security Council, with a veto. After the Beijing government assumed the China seat in 1971 (and the ROC government was expelled), the great majority of nations have switched diplomatic relations from the Republic of China to the People's Republic of China. Japan established diplomatic relations with the PRC in 1972, following the Joint Communiqué of the Government of Japan and the Government of the People's Republic of China, and the U.S. did so in 1979. The number of countries that have established diplomatic relations with Beijing has risen to 171, while 23 maintain diplomatic relations with the Republic of China (or Taiwan).[44] (See also: Political status of Taiwan)

Both the PRC and ROC make it a prerequisite for diplomatic relations that a country does not recognize and conduct any official relations with the other party.

Mao's foreign policies

In the 1947-1962 era, Mao emphasized the desire for international partnerships, on the one hand to more rapidly develop the economy, and on the other to protect against attacks, especially by the U.S. His numerous alliances, however, all fell apart, including the Soviet Union, Vietnam, North Korea, and Albania. He was unable to organize an anti-American coalition. Mao was only interested in what alliances could do for China, and ignored the needs of the partners. From their point of view China appeared unreliable because of its unstable internal situation, typified by the Great Leap Forward. Furthermore, Mao was insensitive to the fears of alliance partners that China was so big, and so inwardly directed, that their needs would be ignored.[45]

With Mao in overall control and making final decisions, Zhou Enlai handled foreign-policy and developed a strong reputation for his diplomatic and negotiating skills.[46] Regardless of those skills, Zhou's bargaining position was undercut by the domestic turmoil initiated by Mao. The Great Leap Forward of 1958-60 was a failed effort to industrialize overnight; it devastated food production and led to millions of deaths from famine. Even more disruptive was the Cultural Revolution of 1966-76, which decimated a generation of leadership. When China broke with Russia around 1960, the main cause was Mao’s insistence that Moscow had deviated from the true principles of communism. The result was that both Moscow and Beijing sponsored rival Communist parties around the world, which expended much of their energy fighting each other. China's focus especially was on the Third World as China portrayed itself as the legitimate leader of the global battle against imperialism and capitalism.[47][48]

Soviet Union and Korean War

After its founding, the PRC's foreign policy initially focused on its solidarity with the Soviet Union, the Eastern Bloc nations, and other communist countries, sealed with, among other agreements, the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance signed in 1950 to oppose China's chief antagonists, the West and in particular the U.S. The 1950–53 Korean War waged by China and its North Korea ally against the U.S., South Korea, and United Nations (UN) forces has long been a reason for bitter feelings. After the conclusion of the Korean War, China sought to balance its identification as a member of the Soviet bloc by establishing friendly relations with Pakistan and other Third World countries, particularly in Southeast Asia.[49]

China's entry into the Korean War was the first of many "preemptive counterattacks". Chinese leaders decided to intervene when they saw their North Korean ally being overwhelmed and no guarantee American forces would stop at the Yalu.[50]

Break with Moscow

By the late 1950s, relations between China and the Soviet Union had become so divisive that in 1960, the Soviets unilaterally withdrew their advisers from China. The two then began to vie for allegiances among the developing world, for China saw itself as a natural champion through its role in the Non-Aligned Movement and its numerous bilateral and bi-party ties. In the 1960s, Beijing competed with Moscow for political influence among communist parties and in the developing world generally. In 1962, China had a brief war with India over a border dispute. By 1969, relations with Moscow were so tense that fighting erupted along their common border. Following the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia and clashes in 1969 on the Sino-Soviet border, Chinese competition with the Soviet Union increasingly reflected concern over China's own strategic position. China then lessened its anti-Western rhetoric and began developing formal diplomatic relations with West European nations.

1980s

Chinese anxiety about Soviet strategic advances was heightened following the Soviet Union's December 1979 invasion of Afghanistan. Sharp differences between China and the Soviet Union persisted over Soviet support for Vietnam's continued occupation of Cambodia, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and Soviet troops along the Sino-Soviet border and in Mongolia—the so-called "three obstacles" to improved Sino-Soviet relations.

In the 1970s and 1980s, China sought to create a secure regional and global environment for itself and foster good relations with countries that could aid its economic development. During the time of Mao, China was a closed country. After his death, authorities led by Deng Xiaoping began instigating reforms. In 1983, 74-year-old Li Xiannian became President of China, nominal head of state of China and one of the longest serving politicians in the leadership of China. He visited many countries and thus began opening China to the world. In 1985, Li Xiannian was the first president of China to visit the U.S. President Li also visited North Korea. 1986 saw the arrival of Queen Elizabeth II in an official visit.[51][52] To this end, China looked to the West for assistance with its modernization drive and for help in countering Soviet expansionism, which it characterized as the greatest threat to its national security and to world peace.

China maintained its consistent opposition to "superpower hegemonism", focusing almost exclusively on the expansionist actions of the Soviet Union and Soviet proxies such as Vietnam and Cuba, but it also placed growing emphasis on a foreign policy independent of both the U.S. and the Soviet Union. While improving ties with the West, China continued to closely follow the political and economic positions of the Third World Non-Aligned Movement, although China was not a formal member.

Tiananmen Square Incident

In the immediate aftermath of the Tiananmen Square incident in June 1989, many countries reduced their diplomatic contacts with China as well as their economic assistance programs. In response, China worked vigorously to expand its relations with foreign countries, and by late 1990, had reestablished normal relations with almost all nations. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in late 1991, China also opened diplomatic relations with the republics of the former Soviet Union.

See also

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- China–United States relations

- History of Sino-Russian relations

- Ten Major Relationships, Mao's policy speech of 1956

- Foreign relations of Taiwan

Notes

- ^ John King Fairbank, "China's Response to the West: Problems and Suggestions." Cahiers d'Histoire Mondiale. Journal of World History. Cuadernos de Historia Mundial 3.2 (1956): 381.

- ^ Brian Catchpole, A map history of modern China (1976), pp 21-23.

- ^ John Yue-wo Wong, Deadly dreams: Opium and the Arrow war (1856-1860) in China (Cambridge UP, 2002).

- ^ Ssu-yü Teng and John King Fairbank, China's response to the West: a documentary survey, 1839-1923(1979) pp 35-37, 134-35.

- ^ Dong Wang, "The Discourse of Unequal Treaties in Modern China," Pacific Affairs (2003) 76#3 pp 399-425.

- ^ Amanda J. Cheney, "Tibet Lost in Translation: Sovereignty, Suzerainty and International Order Transformation, 1904–1906." Journal of Contemporary China 26.107 (2017): 769-783.

- ^ Andre Schmid, "Colonialism and the ‘Korea Problem’ in the Historiography of Modern Japan: A Review Article." Journal of Asian Studies 59.4 (2000): 951-976. online

- ^ Ying-Kit Chan, "Diplomacy and the Appointment of officials in Late Qing China: He Ruzhang and Japan’s Annexation Of Ryukyu." Chinese Historical Review 26.1 (2019): 20-36.

- ^ Robert Lee, France and the exploitation of China, 1885-1901 (1989).

- ^ Anthony Webster, "Business and empire: A reassessment of the British conquest of Burma in 1885." Historical Journal 43.4 (2000): 1003-1025.

- ^ Wendy Palace (2012). British Empire and Tibet 1900-1922. Routledge. p. 257. ISBN 9781134278633.

- ^ Thompson, Larry Clinton William Scott Ament and the Boxer Rebellion: Heroism, Hubris, and the Ideal Missionary (2009), p. 14; Jane Hunter, 'The Gospel of Gentility (1984), p. 6

- ^ Alfred Stead (1901). China and her mysteries. LONDON: Hood, Douglas, & Howard. p. 100. Retrieved 19 February 2011.(Original from the University of California)

- ^ William Woodville Rockhill (1905). China's intercourse with Korea from the XVth century to 1895. LONDON: Luzac & Co. p. 5. Retrieved 19 February 2011.(Colonial period Korea; WWC-5)(Original from the University of California)

- ^ Perry, John Curtis (1964). "The Battle off the Tayang, 17 September 1894". The Mariner's Mirror. 50 (4): 243–259. doi:10.1080/00253359.1964.10657787.

- ^ Frank W. Ikle, "The Triple Intervention. Japan's Lesson in the Diplomacy of Imperialism." Monumenta Nipponica 22.1/2 (1967): 122-130. online

- ^ Catchpole, A map history of modern China (1976), pp 32-33.

- ^ Rhoads Murphey, East Asia (1997) p 325.

- ^ Jung Chang, Empress Dowager Cixi (2013) p. 80

- ^ Robert Bickers, "Revisiting the Chinese maritime customs service, 1854–1950." Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 36.2 (2008): 221-226.

- ^ Henk Vynckier and Chihyun Chang, "'Imperium In Imperio': Robert Hart, the Chinese Maritime Customs Service, and its (Self-)Representations," Biography 37#1 (2014), pp. 69-92 online

- ^ Luke S.K. Kwong, "Chinese politics at the crossroads: Reflections on the Hundred Days Reform of 1898." Modern Asian Studies 34.3 (2000): 663-695.

- ^ Young-Tsu Wong, "Revisionism Reconsidered: Kang Youwei and the Reform Movement of 1898" Journal of Asian Studies 51#3 (1992), pp. 513-544 online

- ^ Catchpole, A map history of modern China (1976), pp 34-35.

- ^ Frank H.H. King, "The Boxer Indemnity—‘Nothing but Bad’." Modern Asian Studies 40.3 (2006): 663-689.

- ^ Ian Nish, The Origins of the Russo-Japanese War (1985).

- ^ Ying-kit Chan, "A Precious Mirror for Governing the Peace: A Primer for Empress Dowager Cixi." Nan Nü 17.2 (2015): 214-244.

- ^ Alison Adcock Kaufman, "In Pursuit of Equality and Respect: China’s Diplomacy and the League of Nations." Modern China 40.6 (2014): 605-638 online.

- ^ Stephen G. Craft, V.K. Wellington Koo and the emergence of modern China (University Press of Kentucky, 2015).

- ^ Michael Schaller, The US Crusade in China, 1938-1945 (1979) p 17.

- ^ Martha Byrd, Chennault: Giving Wings to the Tiger (2003)

- ^ Barbara Tuchman, Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911–45 (1971), pp. 231–232.

- ^ Laura Tyson Li, Madame Chiang Kai-Shek: China's Eternal First Lady (2006).

- ^ Jonathan Fenby, Chiang Kai Shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost (2005) pp 408-14, 428-433.

- ^ Herbert Feis, China Tangle: American Effort in China from Pearl Harbor to the Marshall Mission (1953) pp 376-79.

- ^ Daniel Kurtz-Phelan (2018). The China Mission: George Marshall's Unfinished War, 1945-1947. W. W. Norton. pp. 7, 141. ISBN 9780393243086.

- ^ He Di, "The Most Respected Enemy: Mao Zedong's Perception of the United States" China Quarterly No. 137 (March 1994), pp. 144-158, quotations on page 147. online

- ^ Odd Arne Westad, Restless Empire: China and the World Since 1750 (2012) p 291

- ^ Sergey Radchenko, "Sino-Soviet Relations and the Emergence of the Chinese Communist Regime, 1946–1950: New Documents, Old Story." Journal of Cold War Studies 9.4 (2007): 115-124.

- ^ Bilateral relations between Switzerland and China (page visited on 19 August 2014).

- ^ Consulate-General of the People's Republic of China in Gothenburg. 中国与瑞典的关系. www.fmprc.gov.cn (in Chinese). Gothenburg, Sweden: Consulate-General of the People's Republic of China in Gothenburg. Archived from the original on 2 March 2009. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

瑞典于1950年1月14日承认新中国

- ^ Xinhua (2010-05-07). "60th anniversary of China-Sweden diplomatic relations celebrated". China Daily. Retrieved 2014-08-22.

- ^ Xinhua (2007-06-11). "China-Sweden relations continue to strengthen". China Daily. Retrieved 2014-08-22.

- ^ "Background Note: China". Bureau of Public Affairs. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Michael Yahuda, Towards the End of Isolationism: China's Foreign Policy After Mao (1983) pp 120-22.

- ^ Yahuda, Towards the End of Isolationism (1983) p 18.

- ^ Westad, Restless Empire ch 9

- ^ John W. Garver, China's Quest: The History of the Foreign Relations of the People's Republic (2nd ed. 2018), ppWhat 85, 196-98, 228-231, 264.

- ^ Chen Jian, China's road to the Korean War (1994)

- ^ Freedberg Jr., Sydney J. (26 September 2013). "China's Dangerous Weakness, Part 1: Beijing's Aggressive Idea Of Self-Defense". breakingdefense.com. Breaking Media, Inc. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ^ Anderson, Kurt (7 May 1984). "History Beckons Again". Time. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ "Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip with Chinese President Li Xiannian, October 1986 (colour photo) by - Bridgeman Images - art images & historical footage for licensing". Bridgeman Images. Archived from the original on 2015-02-20. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

((cite web)): Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Further reading

- Clyde, Paul H., and Burton F. Beers. The Far East: A History of Western Impacts and Eastern Responses, 1830-1975 (Prentice Hall, 1975), university textbook.

- Bickers, Robert. The scramble for China: Foreign devils in the Qing Empire, 1832-1914 (2011)

- Chi, Madeleine. China Diplomacy, 1914-1918 (Harvard Univ Asia Center, 1970)

- Cohen, Warren I. America's Response to China: A History of Sino-American Relations (2010) excerpt and text search

- Chien, Frederick Foo. The opening of Korea: a study of Chinese diplomacy, 1876-1885. Shoe String Press, 1967.

- Dallin, David J. The rise of Russia in Asia (Yale UP, 1949) online free to borrow

- Dudden, Arthur Power. The American Pacific: From the Old China Trade to the Present (1992)

- Elleman, Bruce A. Modern Chinese Warfare, 1795-1989 (2001) 363 pp.

- Fairbank, John King, E.O. Reischauer, and Albert M. Craig. East Asia: the modern transformation (Houghton Mifflin, 1965).

- Fairbank, John K. ed.The Chinese World Order: Traditional China’s Foreign Relations (1968)

- Fairbank, John King. "Chinese diplomacy and the treaty of Nanking, 1842." The Journal of Modern History 12.1 (1940): 1-30.

- Feis, Herbert. China Tangle: American Effort in China from Pearl Harbor to the Marshall Mission (1960)

- Fenby, Jonathan. The Penguin History of Modern China: The Fall and Rise of a Great Power 1850 to the Present (3rd ed. 2019) popular history.

- Fogel, Joshua. Articulating the Sino-sphere: Sino-Japanese relations in space and time (2009)

- Garver, John W. Chinese-Soviet Relations, 1937-1945: The Diplomacy of Chinese Nationalism (Oxford UP, 1988).

- Goh, Evelyn. Constructing the US Rapprochement with China, 1961–1974: From'Red Menace'to'Tacit Ally'. Cambridge University Press, 2004. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/c442/4d281fcf6d769947325a45013871e145df6a.pdf

- Grasso, June Grasso, Jay P. Corrin, Michael Kort. Modernization and Revolution in China: From the Opium Wars to the Olympics (4th ed. 2009) excerpt

- Gregory, John S. The West and China since 1500 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003).

- Hara, Takemichi. "Korea, China, and Western Barbarians: Diplomacy in Early Nineteenth-Century Korea." Modern Asian Studies 32.2 (1998): 389-430.

- Hsü, Immanuel C.Y. China's Entrance into the Family of Nations: The Diplomatic Phase, 1858–1880 (1960),

- Hsü, Immanuel C.Y. the rise of modern China (6th ed 1999) University textbook with emphasis on foreign policy

- Jansen, Marius B. Japan and China: From War to Peace, 1894-1972 (1975).

- Kurtz-Phelan, Daniel. The China Mission: George Marshall's Unfinished War, 1945-1947 (WW Norton. 2018).

- Li, Xiaobing. A history of the modern Chinese army (UP of Kentucky, 2007).

- Liu, Ta-jen, and Daren Liu. US-China relations, 1784-1992. Univ Pr of Amer, 1997.

- Liu, Lydia H. The Clash of Empires: The Invention of China in Modern World Making (2006) theoretical study of UK & China excerpt

- Macnair, Harley F. and Donald F. Lach. Modern Far Eastern International Relations (1955) online free

- Mancall, Mark. China at the center: 300 years of foreign policy (1984), Scholarly survey; 540pp

- Morse, Hosea Ballou. The international relations of the Chinese empire Vol. 1 (1910) to 1859; online;

- Nish, Ian. (1990) "An Overview of Relations between China and Japan, 1895–1945." China Quarterly (1990) 124 (1990): 601-623. online

- Perdue, Peter. China marches West: The Qing conquest of Central Eurasia (2005)

- Perkins, Dorothy. Encyclopedia of China (1999)

- Qiang, Zhai. "China and the Geneva Conference of 1954." China Quarterly 129 (1992): 103-122.

- Quested, Rosemary K.I. Sino-Russian relations: a short history (Routledge, 2014) online

- Rowe, William T. China's last Empire: The great Qing (2009)

- Song, Yuwu, ed. Encyclopedia of Chinese-American Relations (McFarland, 2006) [ excerpt].

- Sun, Youli, and You-Li Sun. China and the Origins of the Pacific War, 1931-1941 (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993)

- Sutter, Robert G. Historical Dictionary of Chinese Foreign Policy (2011) excerpt and text search

- Suzuki, Shogo. Civilization and empire: China and Japan's encounter with European international society (2009).

- Taylor, Jay. The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-Sheck and the struggle for modern China (2009)

- Wang, Dong. The United States and China: A History from the Eighteenth Century to the Present (Rowman & Littlefield, 2013), ISBN 0-742-557-82-0

- Wade, Geoff. "Engaging the south: Ming China and Southeast Asia in the fifteenth century." Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 51.4 (2008): 578-638.

- Westad, Odd Arne. Restless Empire: China and the World Since 1750 (Basic Books; 2012) 515 pages; comprehensive scholarly history

- Wills, John E. ed. Past and Present in China's Foreign Policy: From "Tribute System" to "Peaceful Rise". (Portland, ME: MerwinAsia, 2010). ISBN 9781878282873.

- Wright, Mary C. "The Adaptability of Ch'ing Diplomacy." The Journal of Asian Studies 17.3 (1958): 363-381.

- Zhang, Yongjin. China in the International System, 1918-20: the Middle Kingdom at the periphery (Macmillan, 1991)

- Zhang, Feng. "How hierarchic was the historical East Asian system?." International Politics 51.1 (2014): 1-22. Online

After 1948

- Alden, Christopher. China Returns to Africa: A Superpower and a Continent Embrace (2008)

- Barnouin, Barbara, and Changgen Yu. Zhou Enlai: A political life (Chinese University Press, 2006).

- Chang, Gordon H. Friends and Enemies: The United States, China, and the Soviet Union 1948-1972 (1990)

- Foot, Rosemary. The practice of power: US relations with China since 1949 (Oxford UP, 19950.

- Garson, Robert A. The United States and China since 1949: a troubled affair (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1994).

- Garver, John W. China's Quest: The History of the Foreign Relations of the People's Republic (2nd ed. 2018) comprehensive scholarly history. excerpt

- Gosset, David. China's subtle diplomacy, (2011) online

- Hunt, Michael H. The Genesis of Chinese Communist foreign-policy (1996)

- Jian, Chen. China's road to the Korean War (1994)

- Keith, Ronald C. Diplomacy of Zhou Enlai (Springer, 1989).

- Li, Mingjiang. Mao's China and the Sino-Soviet Split: Ideological Dilemma (Routledge, 2013).

- Luthi, Lorenz. The Sino-Soviet split: Cold War and the Communist world (2008)

- MacMillan, Margaret. Nixon and Mao: The week that changed the world. Random House Incorporated, 2008.

- Mishra, Keshav. Rapprochement Across the Himalayas: Emerging India-China Relations Post Cold War Period (1947-2003). (Gyan Publishing House, 2004).

- Poole, Peter Andrews. "Communist China's aid diplomacy." Asian Survey (1966): 622-629. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2642285

- Sutter, Robert G. Foreign Relations of the PRC: The Legacies and Constraints of China's International Politics Since 1949 (Rowman & Littlefield; 2013) 355 pages excerpt and text search

- Tudda, Chris. A Cold War Turning Point: Nixon and China, 1969-1972. LSU Press, 2012.

- Yahuda, Michael. End of Isolationism: China's Foreign Policy After Mao (Macmillan International Higher Education, 2016)

- Zhai, Qiang. The dragon, the lion & the eagle: Chinese-British-American relations, 1949-1958 (Kent State UP, 1994).

- Zhang, Shu Guang. Economic Cold War: America's Embargo against China and the Sino-Soviet Alliance, 1949-1963. Stanford University Press, 2001.

Primary sources

- Teng, Ssu-yü, and John King Fairbank, eds. China's response to the West: a documentary survey, 1839-1923 (Harvard UP, 1979).

| History |

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geography |

| ||||||||||||

| Politics |

| ||||||||||||

| Economy |

| ||||||||||||

| Society |

| ||||||||||||

Foreign relations of Asia | |

|---|---|

| Sovereign states |

|

| States with limited recognition | |