Immigration to Argentina began in several millennia BC with the arrival of cultures from Asia to the Americas through Beringia, according to the most accepted theories, and were slowly populating the American continent. Upon arrival of the Spaniards, the inhabitants of Argentine territory were approximately 300,000[1] people belonging to many civilizations, cultures and tribes.

The history of immigration to Argentina can be divided into several major stages:

- Spanish colonization between the 16th and 18th century, mostly male,[2] largely assimilated with the natives through a process called miscegenation. Although, not all of the current territory was effectively colonized by the Spaniards. The Chaco region, Eastern Patagonia, the current province of La Pampa, the south zone of Córdoba, and the major part of the current provinces of Buenos Aires, San Luis, and Mendoza were maintained under indigenous dominance—Guaycurúes and Wichís from the Chaco region; Huarpes in the Cuyana and north Neuquino; Ranqueles in the east of Cuyo and north from the Pampean region; Tehuelches and Mapuches in the Pampean and Patagonian regions, and Selknam and Yámanas in de Tierra del Fuego archipelago—which were taken over by the Mapuches; first to the east of Cordillera de los Andes, mixing interracially with the Pehuenches in the middle of the 18th century and continuing until 1830 with the indigenous Pampas and north from Patagonia, which were conquered by the Argentine State after its independence.

- The African population, forcibly introduced from sub-Saharan Africa (mainly of Bantu origin), taken to work as slaves in the colony between the 17th and 19th centuries in great numbers.

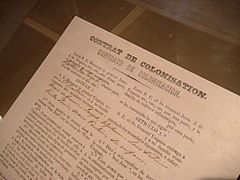

- Immigration mostly European and to a lesser extent from Western Asia, including considerable Arab and Jewish currents, produced between the end of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century (particularly Italians[3] and Spaniards in that quantitative order), promoted by the Constitution of 1852 that prohibited establishing limitations to enter the country to those “strangers that bring through the purpose of working the land, bettering the industries, and introducing and teaching the sciences and the arts”[4] and order the State to promote “European” immigration, even though after predomination of Mediterranean immigrants, from Eastern Europe and the western Asia. Added to this is the Alberdian precept of “to govern is to populate.” These politics were destined to generate a rural social fabric and to finalize the occupation of the Pampean, Patagonian, and Chaco territories, that until the 1880s, were habituated by diverse indigenous cultures.[5]

- European immigration in the 19th century (mainly Italian and Spanish), focused on colonization and sponsored by the government (sometimes on lands conquered from the native inhabitants by the Conquest of the Desert in the last quarter of the century).[6]

- The immigration from nearby countries (Uruguay, Chile, Brazil, Bolivia, and Paraguay) from the 19th to 21st century. These immigration streams date back to the first agro-pottery civilizations that appeared in Argentine territory.[7][8]

- From the 1980s and 1990s, the migration currents especially come from Chile, Paraguay, Bolivia, Peru, Asia (particularly from Korea and China in this period) and Eastern Europe.

- During the 21st century, a part of Argentine migrants and their descendants returned from Europe and the United States. In addition, immigrants from Bolivia, Paraguay, and Peru; now there are also migratory streams from China, Colombia, Cuba, Venezuela, Senegal, Ecuador, Dominican Republic, and Haiti.

- Mostly urban immigration during the era of rapid growth in the late 19th century (from 1880 onwards) and the first half of the 20th century, before and after World War I and also after the Spanish Civil War.[9]

History

Colonial era

The Spanish migration flows which conquered and colonised the area that is now Argentina were mainly three:

- The one which came from the northwest — those Peruvian lands conquered by Diego de Almagro and Francisco Pizarro — being the cities of Lima, Cusco and Potosí the scattering centres.

- The one which came from the west, from Chile, across the Andes; from the cities of Santiago and Coquimbo.

- The one which came from the east, that used the Río de la Plata and its tributaries, especially the Paraná River to settle on the banks thereof. Also, this migration flow settled in Asunción, Paraguay where they colonised much of the region.

The Spanish conquistadores and settlers were mainly from Biscay, as well from Galicia and Portugal, founding cities and establishing estancias for supplies of agricultural and livestock products. The scale of operations was reduced, mainly focused on the domestic market and the provision of the crown.

Support and control of immigration

Since its unification as a country, Argentine rulers intended the country to welcome immigration. Article 25 of the 1853 Constitution reads:

The Federal Government will encourage European immigration, and it will not restrict, limit or burden with any taxes the entrance into Argentine territory of foreigners who come with the goal of working the land, improving the industries and teach the sciences and the arts.

The Preamble of the Constitution dictates a number of goals (justice, peace, defence, welfare and liberty) that apply "to all men in the world who wish to dwell on Argentine soil". The Constitution incorporates, along with other influences, the thought of Juan Bautista Alberdi, who expressed his opinion on the matter in succinct terms: "to govern is to populate".

As a result of policies promoting immigration to the once sparsely populated country 11% of the Argentinan population and 50% of the population of Buenos Aires was made up of newly arrived immigrants by 1869.[10]

The legal and organisational precedents of today's National Migrations Office (Dirección Nacional de Migraciones) can be found in 1825, when Rivadavia created an Immigration Commission. After the Commission was dissolved, the government of Rosas continued to allow immigration. Urquiza, under whose sponsorship the Constitution was drawn, encouraged the establishment of agricultural colonies in the Littoral (western Mesopotamia and north-eastern Pampas).

The first law dealing with immigration policies was Law 817 of Immigration and Colonization, of 1876. The General Immigration Office was created in 1898, together with the Hotel de Inmigrantes (Immigrants' Hotel), in Buenos Aires.

The liberal rulers of the late 19th century saw immigration as the possibility of bringing people from supposedly more civilised, enlightened countries into a sparsely populated land, thus diminishing the influence of aboriginal elements and turning Argentina into a modern society with a dynamic economy. However, immigrants did not bring only their knowledge and skills.

In 1902, a Law of Residence (Ley de Residencia) was passed, mandating the expulsion of foreigners who "compromise national security or disturb public order", and, in 1910, a Law of Social Defence (Ley de Defensa Social) explicitly named ideologies deemed to have such effects. These laws were a reaction by the ruling elite against imported ideas such as labor unionism, anarchism and other forms of popular organisation.

The modern National Migrations Office was created by decree on 4 February 1949, under the Technical Secretariat of the Presidency, in order to deal with the new post-war immigration scenario. New regulations were added to the Office by Law 22439 of 1981 and a decree of 1994, but the current regulations are the Law 25871 of 2004 and the decree 616 of 2010.[11][12]

Features of immigration

A large immigration was experienced all over the country (except for the Northwest), which consisted overwhelmingly by Europeans in a 9/10 ratio. However, Neuquén and Corrientes had a small European population but a large South American immigration (particularly the former), mainly from Chile and Brazil, respectively. The Chaco region (North) had a moderate influx from Bolivia and Paraguay as well.

The majority of immigrants, since the 19th century, have come from Europe, mostly from Italy and Spain. Also notable were Jewish immigrants escaping persecution, giving Argentina the highest Jewish population in Latin America, and the 7th in all the world. The total population of Argentina rose from 4 million in 1895 to 7.9 million in 1914, and to 15.8 million in 1947; during this time the country was settled by 1.5 million Spaniards and 3.8 million Italians between 1861–1920[13] but not all remained. Also arrived were Poles, Russians, French (more than 100,000 each), Germans and Austrians (also more than 100,000), Portuguese, Greeks, Ukrainians, Croats, Czechs, Irish, British, Swiss, Dutch, Hungarians, Scandinavians (the vast majority being Danes ) , and people from other European and Middle Eastern countries, prominently Syria, Lebanon, Palestine. These trends made Argentina the country with the second-largest number of immigrants, with 6.6 million, second only to the United States with 27 million. In addition, Argentine immigrant documents also show immigrants from Australia, South Africa and the United States arriving in Argentina.[14][15][clarification needed]

Most immigrants arrived through the port of Buenos Aires and stayed in the capital or within Buenos Aires Province, as it still happens today. In 1895, immigrants accounted for 52% of the population in the Capital, and 31% in the province of Buenos Aires (some provinces of the littoral, such as Santa Fe, had about 40%, and the Patagonian provinces about 50%). In 1914, before World War I caused many European immigrants to return to their homeland in order to join the respective armies, the overall rate of foreign-born population reached its peak, almost 30%.

A significant number of immigrants settled in the countryside in the interior of the country, especially the littoral provinces, creating agricultural colonies. These included many Jews, fleeing pogroms in Europe and sponsored by Maurice de Hirsch's Jewish Colonization Association; they were later termed "Jewish gauchos". The first such Jewish colony was Moïseville (now the village of Moisés Ville). Through most of the 20th century, Argentina held one of the largest Jewish communities (near 500,000) after the US, France, Israel and Russia, and by far the largest in Latin America (see History of the Jews in Argentina). Argentina is home to a large community from the Arab world, made up mostly of immigrants from Syria, Lebanon and Palestine. Most are Christians of the Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic (Maronite) Churches, with small Muslim and Jewish minorities. Many have gained prominent status in national business and politics, including former president Carlos Menem, the son of Syrian settlers from the province of La Rioja. (see Arab Argentine).

The Welsh settlement of Argentina, whilst not as large as those from other countries, was nevertheless one of the largest in the planet and had an important cultural influence on the Patagonian Chubut Province. Other nationalities have also settled in particular areas of the country, such as Irish in Formosa and the Mesopotamia region, the Ukrainians in Misiones where they constitute approximately 9% of the population.[16]

Well-known and culturally strong are the German-speaking communities such as those of German-descendants themselves (both those from Germany itself, and those ethnic Germans from other parts of Europe, such as Volga Germans), Austrian, and Swiss ones. Strong German-descendant populations can be found in the Mesopotamia region (especially Entre Ríos and Misiones provinces), many neighborhoods in Buenos Aires city (such as Belgrano or Palermo), the Buenos Aires Province itself (strong German settlement in Coronel Suárez, Tornquist and other areas), Córdoba (the Oktoberfest celebration in Villa General Belgrano is specially famous) and all along the Patagonian region, including important cities such as San Carlos de Bariloche (an important tourist spot near the Andes mountain chain, which was especially influenced by German settlements).

The South African Boers Patagonia houses a unique community of South African Boers who settled there after the Second Boer War against the United Kingdom, which ended in 1902. Between 1903 and 1909, up to 800 Boer families trekked by ship to this lonely spot on Argentina's east coast, about 1500 km north of Tierra del Fuego. There are an estimated 100–120 Boer families still living on the land assigned to them by General Julio Roca. They are mainly an agricultural community.[17][18][19][20]

Other nationalities, such as Spaniards, although they have specific localities (such as the centre of Buenos Aires), they are more uniformly present all around the country and form the general background of Argentine population today.

| European immigration to Argentina (1870–1914)[21] | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Period | ||||||||||

| 1857–1859 | 1860–1869 | 1870–1879 | 1880–1889 | 1890–1899 | 1900–1909 | 1910–1919 | 1920–1929 | 1930–1931 | 1940–1949 | 1950–1959 | |

| Belgium | 68 | 518 | 628 | 15,096 | 2,694 | 2,931 | 2,193 | — | — | — | — |

| Switzerland | 219 | 1,562 | 6,203 | 11,569 | 4,875 | 4,793 | 4,578 | — | — | — | — |

| Denmark | — | — | 303 | 1,128 | 1,282 | 3,437 | 4,576 | — | — | — | — |

| France | 720 | 6,360 | 32,938 | 79,422 | 41,048 | 37,340 | 25,258 | — | — | — | — |

| Germany | 178 | 1,212 | 3,522 | 12,958 | 9,204 | 20,064 | 22,148 | 60,130 | — | 1 | 66,327 |

| Italy [clarification needed] | 9,006

3,979 5,027 |

93,602

51,695 41,997 |

156,716

110,994 45,722 |

472,179

98,655 373,524 |

411,764

374,745 37,019 |

848,533

318,841 529,692 |

712,310

459,930 252,380 |

— | — | — | — |

| Netherlands | 37 | 111 | 111 | 4,315 | 675 | 1,622 | 1,264 | — | — | — | — |

| Spain | 2,440 | 20,602 | 44,802 | 148,398 | 114,731 | 672,941 | 598,098 | — | — | — | — |

| Sweden | — | — | 186 | 632 | 490 | 592 | 508 | 441 | — | — | — |

| United Kingdom | 359 | 2,708 | 9,265 | 15,692 | 4,691 | 13,186 | 13,560 | — | — | — | — |

| Russia | 80 | 407 | 464 | 4,155 | 15,665 | 73,845 | 48,002 | — | — | — | — |

| Austria-Hungary | 226 | 819 | 3,469 | 16,479 | 8,681 | 39,814 | 18,798 | — | — | — | — |

| Ottoman Empire | — | — | 672 | 3,537 | 11,583 | 66,558 | 59,272 | — | — | — | — |

| Portugal | 88 | 432 | 656 | 1,852 | 1,612 | 10,418 | 17,570 | 23,406 | 10,310 | 4,230 | 12,033 |

| United States | — | — | 819 | 1,200 | 777 | 2,640 | 2,631 | — | — | — | — |

Legacy of immigration

Argentine popular culture, especially in the Río de la Plata basin, was heavily marked by Italian and Spanish immigration.

Post-independence politicians tried to steer Argentina consistently away from identification with monarchical Spain, perceived as backward and ultraconservative, towards relatively progressive national models like those of France or the United States. Millions of poor peasants from Galicia arriving in Argentina not only did little to alter this position but also immigrated to Argentina because of it, steering clear of the United States and Britain.

Lunfardo, the jargon enshrined in tango lyrics, is laden with Italianisms, often also found in the mainstream colloquial dialect (Rioplatense Spanish). Common dishes in the central area of the country (milanesa, fainá, polenta, pascualina) have Italian names and origins.

Immigrant communities have given Buenos Aires some of its most famous landmarks, such as the Torre de los Ingleses (Tower of the English) or the Monumento de los Españoles (Monument of the Spaniards). Ukrainians, Armenians, Swiss, and many others built monuments and churches at popular spots throughout the capital.

Argentina celebrates Immigrant's Day on September 4 since 1949, by a decree of the Executive Branch. The National Immigrant's Festival is celebrated in Oberá, Misiones, during the first fortnight of September, since 1980. There are other celebrations of ethnic diversity throughout the country, such as the National Meeting and Festival of the Communities in Rosario (typically at the beginning of November). Many cities and towns in Argentina also feature monuments and memorials dedicated to immigration. There are also Immigrant's Festivals (or Collectivities Festivals) throughout the country, for example: Córdoba, Bariloche, Berisso, Esperanza, Venado Tuerto, and Comodoro Rivadavia have their own Immigrant's festivals. These festivals tend to be local, and they are not advertised or promoted nationally like the festivals in Rosario and Oberá.

Immigration in recent times

Besides substantial immigration from neighboring countries, during the middle and late 1990s Argentina received significant numbers of people from Asian countries such as Korea (both North and South), China, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Japan which joined the previously existing Sino-Japanese communities in Buenos Aires. Despite the economic and financial crisis Argentina suffered at the start of the 21st century, people from all over the world continued arriving to the country, because of their immigration-friendly policy and other reasons.

According to official data, between 1992 and 2003 an average 13,187 people per year immigrated legally in Argentina. The government calculates that 504,000 people entered the country during the same period, giving about 345,000 undocumented immigrants. The same source gives a plausible total figure of 750,000 undocumented immigrants currently residing in Argentina.

From 2004 onwards, after Immigration Law 25871[22] was sanctioned, which makes the State responsible for guaranteeing access to health and education for immigrants, many foreigners choose Buenos Aires as their destination to work or study. Between 2006–2008 and 2012–2013 a relatively large group of Senegal nationals (4500 in total) have immigrated to Argentina, 90 percent of which have refugee status.[23]

In April 2006, the national government started the Patria Grande plan to regularize the migratory situation of undocumented immigrants. The plan attempts to ease the bureaucratic process of getting documentation and residence papers, and is aimed at citizens of Mercosur countries and its associated states (Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela). The plan came after a scandal and a wave of indignation caused by fire in a Buenos Aires sweatshop, which revealed the widespread utilization of undocumented Bolivian immigrants as cheap labor force in inhumane conditions, under a regime of virtual debt slavery.

Country of birth of Argentine residents

According to the National Institute of Statistics and Census of Argentina 1,805,957 of the Argentine resident population were born outside Argentina, representing 4.50% of the total Argentine resident population.[24][25][26][27][28]

| Place | Country | 2010 | 2001 | 1991 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 550,713 | 325,046 | 254,115 | |

| 2 | 345,272 | 233,464 | 145,670 | |

| 3 | 191,147 | 212,429 | 247,987 | |

| 4 | 157,514 | 88,260 | 15,939 | |

| 5 | 147,499 | 216,718 | 356,923 | |

| 6 | 116,592 | 117,564 | 135,406 | |

| 7 | 94,030 | 134,417 | 244,212 | |

| 8 | 41,330 | 34,712 | 33,966 | |

| 9 | 19,147 | 10,552 | 9,755 | |

| 10 | 17,576 | 3,876 | 2,638 | |

| 11 | 8,929 | 4,184 | 2,297 | |

| 12 | 8,416 | 10,362 | 15,451 | |

| 13 | 7,321 | 8,290 | 8,371 | |

| 14 | 6,995 | 6,578 | 6,309 | |

| 15 | 6,785 | 9,340 | 13,229 | |

| 16 | 6,428 | 13,703 | 28,811 | |

| 17 | 6,379 | 2,774 | 1,934 | |

| 18 | 6,042 | 3,323 | 2,277 | |

| 19 | 5,661 | 1,497 | N/D | |

| 20 | 4,830 | 8,290 | 3,498 | |

| Other countries | 57,351 | 86,561 | 99,422 | |

| TOTAL | 1,805,957 | 1,531,940 | 1,628,210 | |

See also

- Great European immigration wave to Argentina

- Demographics of Argentina

- Italian Argentines

- German Argentines

- Irish Argentine

- Asian-Argentines

- History of the Jews in Argentina

- Jewish gauchos

- English settlement in Argentina

- Arab Argentines

- Slovene Argentines

- Bulgarians in South America

- Afro Argentines

- Immigration to Uruguay

References

- ^ Ferrer, Aldo (1884). "La economía argentina". Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica. XV: 37.

- ^ Mörner, Magnus (1969). La mezcla de razas en la historia de América Latina. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

((cite book)): CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Foerster, Robert Franz (1919). The Italian Emigration of Our Times. pp. 223–278.

- ^ "Extranjeros". Cuidad y Derechos.

((cite web)): CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Del Gesso, Ernesto (2003). Pampas, araucanos y ranqueles: breve historia de estos pueblos y su final como nación indígena. Ciudad Gótica. p. 145.

((cite book)): CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Argentina: A New Era of Migration and Migration Policy". migrationpolicy.org. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ González, Alberto Rex; Pérez, José A. (1976). "Historia argentina: Argentina indígena, vísperas de la conquista". Editorial Paidós: 42.

- ^ Pierotti, Daniela. "Blanco sobre negro (2º Parte): La discriminación cotidiana y las políticas xenófobas". Archived from the original on February 18, 2008.

- ^ "Origins: History of immigration from Argentina – Immigration Museum, Melbourne Australia". Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ Rocchi, Fernando (2006). Chimneys in the Desert: Industrialization in Argentina During the Export Boom Years, 1870–1930. Stanford University Press. p. 19.

- ^ "Ley de Migraciones". Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ "Decreto 616/2010". Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ Baily, Samuel L., 1999, Immigrants in the Lands of Promise, Italians in Buenos Aires and New York City, 1970-1914. p. 54 ISBN 0801488826

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20070610215422/http://www.cels.org.ar/Site_cels/publicaciones/informes_pdf/1998.Capitulo7.pdf

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20110814202421/http://docentes.fe.unl.pt/~satpeg/PapersInova/Labor%20and%20Immigration%20in%20LA-2005.pdf

- ^ Wasylyk, Mykola (1994). Ukrainians in Argentina (Chapter), in Ukraine and Ukrainians Throughout the World, edited by Ann Lencyk Pawliczko, University of Toronto Press: Toronto, pp. 420–443

- ^ "I Luv SA: The Argentinian Boers: The Oldest Boer Diaspora". Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ "End of era for Argentina's Afrikaners". IOL. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ "The Boers at the end of the world". November 10, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ "Argentinian community of bitter Boers dwindles". Business Day Live. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ Migration from Europe to the Americas: A Panel-Data Analysis

- ^ http://www.migraciones.gov.ar/pdf_varios/campana_grafica/pdf/Libro_Ley_25.871.pdf

- ^ Firpo, Javier (September 23, 2018). "Senegaleses en Argentina: estudian español para dejar de vender en la calle". www.clarin.com.

- ^ "Tendencias recientes de la inmigración internacional" [Recent trends in international migration] (PDF). Revista informativa del censo 2001 (in Spanish) (12). INDEC. February 2004. ISSN 0329-7586. Archived from the original on November 14, 2011.

((cite journal)): CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Investigación de la Migración Internacional en Latinoamérica (IMILA) Archived 2008-05-14 at the Wayback Machine Centro Latinoamericano y Caribeño de Demografía (CELADE). Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL).

- ^ "Censo Nacional de Población, Hogares y Viviendas 2001" [National Census of Population and Housing 2001]. INDEC – Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (in Spanish). Archived from the original on June 3, 2014.

- ^ "Cuadro P6. Total del país. Población total nacida en el extranjero por lugar de nacimiento, según sexo y grupos de edad. Año 2010" (Press release). INDEC. Archived from the original on September 2, 2011. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ^ Censo 2010 Archived October 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine INDEC.

External links

- Centro de Estudios Migratorios de LAtinoamericanos (CEMLA), a searchable immigration database of Argentina by name, last name and date period (alternative URL for this database search)

- (in English) CasaHistoria — European immigration to Argentina

- Immigration and banking for expats in Argentina

- Immigrant's Day on the Ministry of Education website

- Conformación de la Población Argentina

- Bajaron de los barcos ("They came down from the ships") – figures, timeline and other details of Argentine immigration

- Patria Grande, National Program of Migratory Documentary Normalization

- Obera and the National Immigrant Festival, news and video about this event (in Spanish)

- La Nación, 17 April 2006, Más de 10 mil inmigrantes iniciaron trámites de regularización

- "Inmigración a la Argentina (1850–1950)" – monografias.com

- Recent efforts among US immigrants to Argentina at mutual aid, 2009 (English)

- [1]

- Migration Information Source

- [2]

- Immigration policy in Argentina

- Visas and Procedures. How do you get a visa?

Ancestral background of Argentine citizens | |||||||||||||||||||

| Africa | |||||||||||||||||||

| Americas |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Asia | |||||||||||||||||||

| Europe |

| ||||||||||||||||||