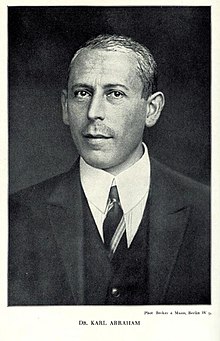

Karl Abraham | |

|---|---|

Abraham, c. 1920 | |

| Born | 3 May 1877 |

| Died | 25 December 1925 (aged 48) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychiatry |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Psychoanalysis |

|---|

|

Karl Abraham (German: [ˈaːbʁaham]; 3 May 1877 – 25 December 1925) was an influential German psychoanalyst, and a collaborator of Sigmund Freud, who called him his 'best pupil'.[1][2]

Abraham was born in Bremen, Germany. His parents were Nathan Abraham, a Jewish religion teacher (1842–1915), and his wife (and cousin) Ida (1847–1929).[3] His studies in medicine enabled him to take a position at the Burghölzli Swiss Mental Hospital, where Eugen Bleuler practiced. The setting of this hospital initially introduced him to the psychoanalysis of Carl Gustav Jung.[citation needed]

In 1907, he had his first contact with Sigmund Freud, with whom he developed a lifetime relationship. Returning to Germany, he founded the Berliner Society of Psychoanalysis in 1910.[4] He was the president of the International Psychoanalytical Association from 1914 to 1918 and again in 1925.

Karl Abraham collaborated with Freud on the understanding of manic-depressive illness, leading to Freud's paper on 'Mourning and Melancholia' in 1917. He was the analyst of Melanie Klein during the years 1924–1925, and of a number of other British psychoanalysts, including Edward Glover and Alix Strachey. He was a mentor for an influential group of German analysts, including Karen Horney, Helene Deutsch, and Franz Alexander.

Karl Abraham studied the role of infant sexuality in character development and mental illness and, like Freud, suggested that if psychosexual development is fixated at some point, mental disorders will likely emerge. He described the personality traits and psychopathology that result from the oral and anal stages of development (1921).[5]

Abraham observed his only daughter, Hilda, reporting on her reaction to enemas and infantile masturbation by her brother. He asked that secrets be shared with him but he was careful to respect her privacy and some reports were not published until after Hilda's death. Hilda was later to become a psychoanalyst.[6]

In the oral stage of development, the first relationships children have with objects (caretakers) determine their subsequent relationship to reality. Oral satisfaction can result in self-assurance and optimism, whereas oral fixation can lead to pessimism and depression. Moreover, a person with an oral fixation will present a disinclination to take care of themself and will require others to look after them. This may be expressed through extreme passivity (corresponding to the oral benign suckling substage) or through a highly active oral-sadistic behaviour (corresponding to the later sadistic biting substage).[5]

In the anal stage, when the training in cleanliness starts too early, conflicts may result between a conscious attitude of obedience and an unconscious desire for resistance. This can lead to traits such as frugality, orderliness and obstinacy, as well as to obsessional neurosis as a result of anal fixation (Abraham, 1921). In addition, Abraham based his understanding of manic-depressive illness on the study of the painter Segantini: an actual event of loss is not itself sufficient to bring the psychological disturbance involved in melancholic depression. This disturbance is linked with disappointing incidents of early childhood; in the case of men always with the mother (Abraham, 1911). This concept of the prooedipal “bad” mother was a new development in contrast to Freud’s oedipal mother and paved the way for the theories of Melanie Klein.[7]

Another important contribution is his work “A short study of the Development of the Libido”,[8] where he elaborated on Freud’s “Mourning and Melancholia” (1917) and demonstrated the vicissitudes of normal and pathological object relations and reactions to object loss.

Moreover, Abraham investigated child sexual trauma and, like Freud, proposed that sexual abuse was common among psychotic and neurotic patients. Furthermore, he argued (1907) that dementia praecox is associated with child sexual trauma, based on the relationship between hysteria and child sexual trauma demonstrated by Freud.

Abraham (1920) also showed interest in cultural issues. He analyzed various myths suggesting their relation to dreams (1909) and wrote an interpretation of the spiritual activities of the Egyptian monotheistic Pharaoh Amenhotep IV (1912).

Abraham died prematurely on December 25, 1925, from complications of a lung infection and may have suffered from lung cancer.[9]