A literacy test, in the context of American political history from the 1890s to the 1920s, refers to the government practice of testing the literacy of potential citizens at the federal level, and potential voters at the state level.

Immigration

In 1906, the powerful House Speaker Joseph Gurney Cannon worked aggressively to defeat a proposed literacy test for immigrants. A product of the western frontier, Cannon felt that moral probity was the only acceptable test for the quality of an immigrants. He worked with Secretary of State Elihu Root and President Theodore Roosevelt to set up the "Dillingham Commission," a blue ribbon body of experts that produced a 41-volume study of immigration. The Commission recommended a literacy test and the possibility of annual quotas.[1]

The American Federation of Labor took the lead in promoting literacy tests that would exclude illiterate immigrants, primarily from Southern and Eastern Europe. A majority of the labor union membership were immigrants or sons of immigrants from Germany Scandinavia and Britain, but the literacy test would not hinder immigration from those countries.[2]

The federal government first employed literacy tests as part of the immigration process in 1917. A federal immigration literacy test had been proposed several times earlier, but adoption had been blocked by Presidential vetoes,[3] and by Congress members seeking support from immigrant voters.[4]

Voting

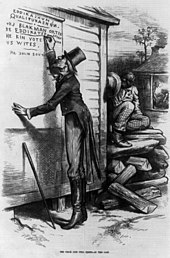

Southern state legislatures employed literacy tests as part of the voter registration process starting in the late 19th century.

Literacy tests, along with poll taxes and extra-legal intimidation,[5] were used to deny suffrage to African-Americans. The first formal voter literacy tests were introduced in 1890.

Whites were exempted from the literacy test if they could meet alternate requirements (the grandfather clause) that, in practice, excluded blacks. The Grandfather Clause allowed an illiterate person to vote if he could show descent from someone who was eligible to vote before 1867 (when only whites could vote). Grandfather clauses were ruled unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court in the case of Guinn v. United States (1915). Nevertheless, literacy tests continued to be used to disenfranchise blacks. The tests were usually administered orally by white local officials, who had complete discretion over who passed and who failed.[6] Examples of questions asked of Blacks in Alabama included: naming all sixty-seven county judges in the state, naming the date on which Oklahoma was admitted to the Union, and declaring how many bubbles are in a bar of soap.[7]

Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment would have penalized states which excluded adult males from voting (whether by literacy tests or by any other means) by proportionately reducing their representation in Congress, but this provision was never enforced. In 1959, the U.S. Supreme Court held that literacy tests were not necessarily violations of Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment nor of the Fifteenth Amendment. Lassiter v. Northampton Election Board (1959). Southern states abandoned the literacy test only when forced to do so by federal legislation in the 1960s. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 provided that literacy tests used as a qualification for voting in federal elections be administered wholly in writing and only to persons who had completed six years of formal education. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 suspended the use of literacy tests in all states or political subdivisions in which less than 50 percent of voting-age residents were registered as of November 1, 1964, or had voted in the 1964 presidential election. In a series of cases, the Supreme Court of the United States upheld the legislation[8] and restricted the use of literacy tests for non-English-speaking citizens, Katzenbach v. Morgan. Since the passage of this legislation, black registration in the South has increased substantially.

Canada

Anglophone Canada heavily promoted immigration from Europe in the early 20th century, while blocking any further immigration from Asia. British and Irish immigrants were all welcome; at issue was a literacy test that would screen out most applicants from Italy, Russia and other parts of Southern and Eastern Europe. In 1919 major new legislation was passed (at a time when the Francophiles were virtually powerless in Parliament). A wide range of public opinion expressed mounting fears and culturally based stereotypes along with articulations of idealized national identity through the Canadianization of immigrants.[9]

Worldwide

The best selection of immigrants for two centuries has been a major theme in the politics of Europe and other countries as well.[10][11]

See also

References

- ^ Robert F. Zeidel, "Hayseed Immigration Policy: 'Uncle Joe' Cannon and the Immigration Question," Illinois Historical Journal (1995) 88#3 pp 173-188.

- ^ A. T. Lane, "American Trade Unions, Mass Immigration and the Literacy Test: 1900-1917," Labor History (1984) 25#1 pp 5-25.

- ^ Claudia Goldin, "The political economy of immigration restriction in the United States, 1890 to 1921" in ;;The regulated economy: A historical approach to political economy (U. of Chicago Press, 1994). 223-258

- ^ “Echoes of Ellis Island,” Los Angeles Times, July 4, 2013, p. A19

- ^ http://www.crmvet.org/info/lithome.htm

- ^ Robert Caro, Master of the Senate, p. 691

- ^ Caro, Master of the Senate, p. x

- ^ United States v. Mississippi, 380 U.S. 128 (1965), South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S.301

- ^ Lorna McLean, "'To Become Part of Us': Ethnicity, Race, Literacy and the Canadian Immigration Act of 1919," Canadian Ethnic Studies, (2004) 36#2 pp 1-28

- ^ Anna Maria Mayda, "Who is against immigration? A cross-country investigation of individual attitudes toward immigrants," Review of Economics and Statistics (2006) 88#3 pp 510-530.

- ^ Timothy J. Hatton and Jeffrey G. Williamson, Global migration and the world economy: Two centuries of policy and performance (MIT Press, 2005)

External links

- Are You "Qualified" to Vote? Alabama literacy test ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- Take the Impossible “Literacy” Test Louisiana Gave Black Voters in the 1960s ~ Slate

- Naturalization literacy test still in use today[dead link]

- Citizenship [Literacy] Test from the Georgia Voters' Registration Acts of 1949 and 1958. From the collection of the Georgia Archives.

| Learning | |

|---|---|

| Locations | |

| Institutions | |

| People | |

| Other types |

|

| Related | |