Transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth

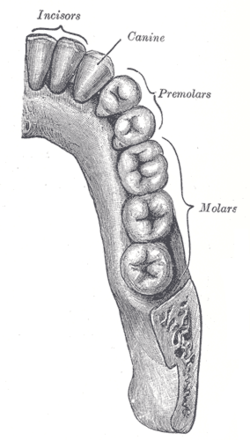

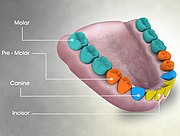

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mouth.[1][2][3] They have at least two cusps. Premolars can be considered transitional teeth during chewing, or mastication. They have properties of both the canines, that lie anterior and molars that lie posterior, and so food can be transferred from the canines to the premolars and finally to the molars for grinding, instead of directly from the canines to the molars.[4]

Human anatomy

The premolars in humans are the maxillary first premolar, maxillary second premolar, mandibular first premolar, and the mandibular second premolar.[1][3] Premolar teeth by definition are permanent teeth distal to the canines, preceded by deciduous molars.[5]

Morphology

There is always one large buccal cusp, especially so in the mandibular first premolar. The lower second premolar almost always presents with two lingual cusps.[6]

The lower premolars and the upper second premolar usually have one root. The upper first usually has two roots, but can have just one root, notably in Sinodonts, and can sometimes have three roots.[7][8]

Premolars are unique to the permanent dentition. Premolars are referred to as bicuspid (has two main cusps), a buccal and a palatal/lingual cusp which are separated by a mesiodistal occlusal fissure.

The maxillary premolars are trapezoidal in shape. Whilst the mandibular premolars are rhomboidal in shape.

Maxillary first premolar

- The crown of the tooth appears ovoid, wider buccally than palatally

- From a buccal view, the first premolar is similar to the adjacent canine

- Roots: Two roots buccal and palatal. Sometimes (40%) there is only one root.

Maxillary second premolar

- Similar to maxillary first premolar but the mesio-buccal and disto-buccal corners are rounder

- The two cusps are smaller and more equal in size

- Shorter occlusal fissure

- Usually one root

Mandibular first premolar

- The smallest premolar out of all four

- Dominant buccal cusp and a very small lingual cusp

- The buccal cusp is broad and the lingual cusp is less than half the size of the buccal cusp.

- Two-thirds of the buccal surface can be seen from the occlusal aspect

- A single conical root with an oval/round cross section. The root is grooved longitudinally both mesially and distally.

Mandibular second premolar

- The crown is larger than the mandibular first premolar

- Lingual cusp is smaller than the buccal cusp but better developed.

- The lingual and buccal cusp is separated by a well defined mesiodistal occlusal fissure

- The lingual cusp is divided into two; the mesiolingual and distolingual cusps with the mesiolingual cusp being higher and wider than the distolingual.

- Root: Single conical root, oval/round in cross section.

Orthodontics

The four first premolars are the most commonly removed teeth, in 48.8% of cases, when teeth are removed for orthodontic treatment (which is in 45.8% of orthodontic patients). The removal of only the maxillary first premolars is the second likeliest option, in 14.5% of cases.[10] The practice of premolar extraction developed in the 1940s in the United States, and was initially greatly contested in the orthodontic field, due to the changes to the facial structure caused by the retraction of the arches. Known as "the Great Controversy in Orthodontics," the debate over extractions was revived in the 1990s, following numerous patient reports of health consequences due to extraction/retraction, from TMD to Obstructive Sleep Apnea, and published research on the reduction of the pharyngeal airway due to the retraction.[11] The debate has to date not been resolved.[dubious – discuss] Today more and more orthodontists are avoiding the use of what is termed 'extraction therapy,' and in the United States, the official rate is now 25%.

Other mammals

In primitive placental mammals there are four premolars per quadrant, but the most mesial two (closer to the front of the mouth) have been lost in catarrhines (Old World monkeys and apes, including humans). Paleontologists therefore refer to human premolars as Pm3 and Pm4.[12][13]