| Rear Window | |

|---|---|

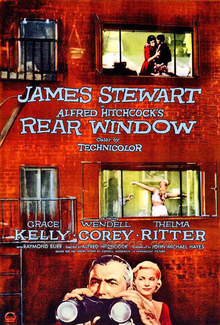

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Written by | Cornell Woolrich (story) John Michael Hayes |

| Produced by | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Starring | James Stewart Grace Kelly Thelma Ritter Wendell Corey Raymond Burr |

| Cinematography | Robert Burks |

| Edited by | George Tomasini |

| Music by | Franz Waxman |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures Universal Studios |

Release date | August 1, 1954 |

Running time | 112 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | US$1 million (est.)[1] |

Rear Window is a 1954 American suspense film directed by Alfred Hitchcock, written by John Michael Hayes based on Cornell Woolrich's 1942 short story "It Had to Be Murder". It stars James Stewart as photographer L. B. "Jeff" Jefferies, who spies on his neighbors while recuperating from a broken leg; Grace Kelly as Jeff's girlfriend Lisa Fremont; Thelma Ritter as his home care nurse Stella; Wendell Corey as his friend, police detective Tom Doyle; and Raymond Burr as Lars Thorwald, one of his neighbors.

The film is considered by many film-goers, critics, and scholars to be one of Hitchcock's best and most thrilling pictures.[2] It received four Academy Award nominations, was added to the United States National Film Registry in 1997, and was ranked #48 on AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition).

Plot

After breaking his leg in one of his dangerous photography assignments, Jeff is confined to a wheelchair in his Greenwich Village apartment, whose rear window looks out onto a small courtyard and several other apartments. During a summer heat wave, he passes the time by watching his neighbors, who keep their windows open to stay cool. The tenants he can see include a dancer, a lonely woman, a songwriter (Bagdasarian), several married couples, and Thorwald, a salesman with a bedridden wife.

After Thorwald makes repeated late-night trips carrying a large case, Jeff notices that Thorwald's wife is gone and sees Thorwald cleaning a large knife and handsaw. Later, Thorwald ties a large packing crate with heavy rope and has moving men haul it away. After discussing these observations, Jeff, Stella and Lisa conclude that Thorwald murdered his wife.

Jeff asks Doyle to look into the situation, but Doyle finds nothing suspicious. Soon a neighbor's dog is found dead with its neck broken. When a woman sees the dog and screams, the neighbors all rush to their windows to see what has happened, except for Thorwald, whose cigar can be seen glowing as he sits in his dark apartment.

Convinced that Thorwald is guilty after all, Jeff has Lisa slip an accusatory note under Thorwald's door so Jeff can watch his reaction when he reads it. Then, as a pretext to get Thorwald away from his apartment, Jeff telephones him and arranges a meeting at a bar. He thinks Thorwald may have buried something in the courtyard flower patch and then killed the dog to keep it from digging it up. When Thorwald leaves, Lisa and Stella dig up the flowers but find nothing.

Lisa then climbs the fire escape to Thorwald's apartment and squeezes in through an open window. When Thorwald returns and grabs Lisa, Jeff calls the police, who arrive in time to save her. With the police present, Jeff sees Lisa with her hands behind her back, wiggling her finger with Mrs. Thorwald's wedding ring on it. Thorwald also sees this, realizes that she is signaling to someone, and notices Jeff across the courtyard.

Jeff phones Doyle, now convinced that Thorwald is guilty of something, and Stella heads for the police station to bail Lisa out, leaving Jeff alone. He soon realizes that Thorwald is coming to his apartment. When Thorwald enters the apartment and approaches him, Jeff repeatedly sets off his flashbulbs, temporarily blinding Thorwald. Thorwald grabs Jeff and pushes him towards the open window as Jeff yells for help. Jeff falls to the ground just as some police officers enter the apartment and others run to catch him. Thorwald confesses the murder of his wife and the police arrest him.

A few days later, the heat has lifted and Jeff rests peacefully in his wheelchair, now with casts on both legs. The lonely neighbor woman chats with the songwriter in his apartment, the dancer's lover returns home from the Army, the couple whose dog was killed have a new dog, and the newly married couple are bickering. In the last scene of the film, Lisa reclines beside Jeff, appearing to read a book on foreign travel in order to please him, but as soon as he is asleep, she puts the book down and happily opens a fashion magazine.

Cast

- James Stewart as L. B. "Jeff" Jefferies, an adventure-loving professional photographer

- Grace Kelly as Lisa Carol Fremont, Jeff's girlfriend, a pampered young socialite

- Wendell Corey as Det. Lt. Thomas J. Doyle, an old buddy of Jeff's from the Army Air Corps, now a police detective

- Thelma Ritter as Stella, a nurse

- Raymond Burr as Lars Thorwald, Jeff's neighbor, a salesman

- Judith Evelyn as Miss Lonelyhearts, a middle-aged woman who lives alone and enacts her romantic fantasies

- Ross Bagdasarian as Songwriter

- Georgine Darcy as Miss Torso, a young dancer who practices in her underwear

- Sara Berner as Wife living above Thorwalds

- Frank Cady as Husband living above Thorwalds

- Jesslyn Fax as Sculptor neighbor with hearing aid

- Rand Harper as Newlywed man

- Irene Winston as Mrs. Anna Thorwald

- Havis Davenport as Newlywed woman

Director Alfred Hitchcock makes his traditional cameo appearance in the songwriter's apartment, where he is seen winding a clock.

Production

The film was shot entirely at Paramount studios, including an enormous set on one of the soundstages, and employed the Eastmancolor process in use at the time.[3] There was also careful use of sound, including natural sounds and music drifting across the apartment building courtyard to James Stewart's apartment. At one point, the voice of Bing Crosby can be heard singing "To See You Is to Love You", originally from the 1952 Paramount film Road to Bali. Also heard on the soundtrack are versions of songs popularized earlier in the decade by Nat King Cole ("Mona Lisa", 1950) and Dean Martin ("That's Amore", 1952), along with segments from Leonard Bernstein's score for Jerome Robbins's ballet Fancy Free (1944), Richard Rodgers's song "Lover" (1932), and "M'appari tutt'amor" from Friedrich von Flotow's opera Martha (1844).

Hitchcock used costume designer Edith Head on all of his Paramount films.

Although veteran Hollywood composer Franz Waxman is credited with the score for the film, his contributions were limited to the opening and closing titles and the piano tune played by one of the neighbors during the film. This was Waxman's final score for Hitchcock. The director used primarily "natural" sounds throughout the film.[4]

Reception

A "benefit world premiere" for the film, with United Nations officials and "prominent members of the social and entertainment worlds"[5] in attendance, was held on August 4, 1954 in New York City, with proceeds going to the American-Korean Foundation (an aid organization founded soon after the end of the Korean War[6] and headed by President Eisenhower's brother). Critic Bosley Crowther of The New York Times attended that premiere, and in his review called the film a "tense and exciting exercise" and Hitchcock a director whose work has a "maximum of build-up to the punch, a maximum of carefully tricked deception and incidents to divert and amuse"; Crowther also notes:[5]

- Mr. Hitchcock's film is not "significant." What it has to say about people and human nature is superficial and glib. But it does expose many facets of the loneliness of city life and it tacitly demonstrates the impulse of morbid curiosity. The purpose of it is sensation, and that it generally provides in the colorfulness of its detail and in the flood of menace toward the end.

Time called it "just possibly the second most entertaining picture (after The 39 Steps) ever made by Alfred Hitchcock" and a film in which there is "never an instant...when Director Hitchcock is not in minute and masterly control of his material."; the review did note the "occasional studied lapses of taste and, more important, the eerie sense a Hitchcock audience has of reacting in a manner so carefully foreseen as to seem practically foreordained."[7] Variety called the film "one of Alfred Hitchcock's better thrillers" which "combines technical and artistic skills in a manner that makes this an unusually good piece of murder mystery entertainment."[8]

Nearly 30 years after the film's initial release, Roger Ebert reviewed the Universal re-release in October 1983, after Hitchcock's estate was settled. He said the film "develops such a clean, uncluttered line from beginning to end that we're drawn through it (and into it) effortlessly. The experience is not so much like watching a movie, as like ... well, like spying on your neighbors. Hitchcock traps us right from the first....And because Hitchcock makes us accomplices in Stewart's voyeurism, we're along for the ride. When an enraged man comes bursting through the door to kill Stewart, we can't detach ourselves, because we looked too, and so we share the guilt and in a way we deserve what's coming to him."[9]

On the website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has been universally praised, garnering a 100% certified fresh rating, based on 58 reviews.

Analysis

Hitchcock's fans and film scholars have taken particular interest in the way the relationship between Jeff and Lisa can be compared to the lives of the neighbors they are spying upon. The film invites speculation as to which of these paths Jeff and Lisa will follow. Many of these points are considered in Tania Modleski's feminist theory book, The Women Who Knew Too Much:[10]

- Thorwald and his wife are a reversal of Jeff and Lisa—Thorwald looks after his invalid wife just as Lisa looks after the invalid Jeff. However, Thorwald's hatred of his nagging wife mirrors Jeff's arguments with Lisa.

- The newlywed couple initially seem perfect for each other (they spend nearly the entire movie in their bedroom with the blinds drawn), but at the end we see that their marriage to become more realistic as the wife begins to nag the husband. Similarly, Jeff is afraid of being 'tied down' by marriage to Lisa.

- The middle-aged couple with the dog seem content living at home. They have the kind of uneventful lifestyle that horrifies Jeff.

- The Songwriter, a music composer, and Miss Lonelyhearts, a depressed spinster, lead frustrating lives, and at the end of the movie find comfort in each other: The composer's new tune draws Miss Lonelyhearts away from suicide, and the composer thus finds value in his work. There is a subtle hint in this tale that Lisa and Jeff are meant for each other, despite his stubbornness. The piece the composer creates is called "Lisa's Theme" in the credits.

The characters themselves verbally point out a similarity between Lisa and Miss Torso (played by Georgine Darcy) — the scantily-clad ballet dancer who has all-male parties.

Other analysis, including Francois Truffaut in Cahiers du cinéma in 1954, centers on the relationship between Jeff and the other side of the apartment block, seeing it as a symbolic relationship between spectator and screen. Film theorist Mary Ann Doane has made the argument[citation needed] that Jeff, representing the audience, becomes obsessed with the screen, where a collection of storylines are played out. This line of analysis has often followed a feminist approach to interpreting the film. It is Doane who, using Freudian analysis to claim women spectators of a film become "masculinized", pays close attention to Jeff's rather passive attitude to romance with the elegant Lisa, that is, until she crosses over from the spectator side to the screen, seeking out the wedding ring of Thorwald's murdered wife. It is only then that Jeff shows real passion for Lisa. In the climax, when he is pushed through the window (the screen), he has been forced to become part of the show.

Other issues such as voyeurism and feminism are analyzed in John Belton's book Alfred Hitchcock's "Rear Window".

Rear Window is a voyeuristic film. As Stella (Thelma Ritter) tells Jeff, "We've become a race of Peeping Toms." This applies equally to the cinema as well as to real life. Stella invokes the specifically sexual pleasures of looking that is identified as exemplary of classical Hollywood. The majority of the film is seen through Jeff's visual point of view and his mental perspective. Stella's words sum up Hitchcock's broader project as film maker, namely, to implicate us as spectators. While Jeff is watching the rear window people, we too are being "peeping toms" as we watch him, and the people he watches as well. As a voyeristic society, we take personal pleasure in watching what is going on around us.

Legacy

The film received four Academy Award nominations: Best Director for Alfred Hitchcock, Best Screenplay for John Michael Hayes, Best Cinematography, Color for Robert Burks, Best Sound Recording for Loren L. Ryder, Paramount Pictures. John Michael Hayes won a 1955 Edgar Award for best motion picture.

In 1997, Rear Window was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Rear Window was restored by the team of Robert A. Harris and James C. Katz for its 1999 limited theatrical re-release and the Collector's Edition DVD release in 2000.

American Film Institute recognition

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies #42

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills #14

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) #48

- AFI's 10 Top 10 #3 Mystery[11][11]

Ownership

Ownership of the copyright in Woolrich's original story was eventually litigated before the United States Supreme Court in Stewart v. Abend, 495 U.S. 207 (1990). The film was copyrighted in 1954 by Patron Inc. — a production company set up by Hitchcock and Stewart. As a result, Stewart and Hitchcock's estate became involved in the Supreme Court case.

Rear Window is one of several of Hitchcock's films originally released by Paramount Pictures, for which Hitchcock retained the copyright, and which was later acquired by Universal Studios in 1983 from Hitchcock's estate.

Influence

Rear Window has been repeatedly re-told, parodied, or referenced.

Film

- The Brian De Palma film Body Double pays homage to Rear Window, and also borrows heavily from Hitchcock's Vertigo.

- The TV movie Rear Window (1998) starring Christopher Reeve and Daryl Hannah is a remake.

- The film Head Over Heels (2001) starring Freddie Prinze Jr., in which a young woman falls for a man she believes she saw commit a murder, closely follows the plot of Rear Window.

- Marcos Bernstein's The Other Side of The Street (2004) also makes a reference to Rear Window, albeit with a Brazilian twist.

- Robert Zemeckis's What Lies Beneath is another film that pays tribute to this film and other Hitchcock features.

- The That 70's Show episode Too Old to Trick or Treat, Too Young to Die parodies several Hitchcock films, including Rear Window.

- Clubhouse Detectives (1996) is a retelling, aimed at a younger audience, where a young boy sees a neighbor kill a student and bury her under his floor boards.

Disturbia (2007) is a modern day retelling, with the protagonist (Shia LaBeouf) under house arrest instead of laid up with a broken leg and who believes that his neighbor is a serial killer rather than having committed a single murder. On September 5, 2008, the Sheldon Abend Trust sued Steven Spielberg, Dreamworks, Viacom, and Universal Studios, alleging that the producers of Disturbia violated the rights of Abend and the Woolrich estate, by not acquiring the rights to the Woolrich story.

Television

Rear Window was remade as a made-for-television movie of the same name in 1998, with an updated storyline in which the lead character is paralyzed and lives in a high-tech home filled with assistive technology. Actor Christopher Reeve, himself paralyzed as the result of a 1995 horse-riding accident, was cast in the lead role. The telefilm also starred Daryl Hannah, Robert Forster, Ruben Santiago-Hudson, and Anne Twomey. It aired November 22, 1998 on the ABC television network.

The film's plot was parodied in The Simpsons episode Bart of Darkness. Invader Zim also spoofs the movie in one scene in A Room with a Moose. The Rocko's Modern Life episode "Ed is Dead" also borrows elements from the film. Home movies also parodies the film's plot in the 2004 episode "definite possible murder".

On November 14, 2009, the film was parodied on Saturday Night Live, with host January Jones playing the part of Lisa Fremont. It was also the week of what would have been the 80th birthday of Grace Kelly.

Music

American recording artist Lady Gaga included a reference to Rear Window (and two other Hitchcock films, Vertigo and Psycho) in her 2009 single Bad Romance from her album The Fame Monster, singing the line "I want your psycho / your vertigo shtick / want you in my rear window / baby, you're sick."

Notes

- ^ Rear Window (Box office/business) at IMDb

- ^ Rear Window Movie Reviews, Pictures - Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ Rear Window (Additional details) at IMDb

- ^ DVD documentary

- ^ a b A 'Rear Window' View Seen at the Rivoli, an August 5, 1954 review from The New York Times

- ^ Statement by the President on the fund-raising campaign of the American-Korean Foundation from a University of California, Santa Barbara website

- ^ The New Pictures, an August 2, 1954 review from Time magazine

- ^ Review of Rear Window, a July 14, 1954 article from Variety magazine

- ^ 1983 Review of Rear Window re-release by Roger Ebert

- ^ Modleski, Tania, The Women Who Knew Too Much: Hitchcock and Feminist Theory (New York: Routledge, Chapman & Hall, Inc., 1989) ISBN 0-415-97362-7

- ^ a b "AFI's 10 Top 10". American Film Institute. 2008-06-17. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

External links

- Rear Window at IMDb

- Rear Window at the TCM Movie Database

- Rear Window at AllMovie

- Rear Window at Box Office Mojo

- Rear Window at The Numbers

- Detailed review