Valeska Gert (11 January 1892 – c. 16 March 1978) was a German dancer, pantomime, cabaret artist, actress and pioneering performance artist.

Gert was born as Gertrud Valesca Samosch in Berlin to a Jewish family. She was the eldest daughter of manufacturer Theodor Samosch and Augusta Rosenthal.[1] Exhibiting no interest in academics or office work,[1] she began taking dance lessons at the age of nine.[2] This, combined with her love of ornate fashion, led her to a career in dance and performance art.[1] In 1915, she studied acting with Maria Moissi, and dance with Rita Sacchetto.[3]

World War I had a negative effect on her father's finances, forcing her to rely on herself far more than other bourgeois daughters typically might.[1] As World War I raged, Gert joined a Berliner dance group and created revolutionary satirical dance.[2] Following engagements at the Deutsches Theater and the Tribüne in Berlin, Gert was invited to perform in expressionist plays in Dadaist mixed media art nights.[1] Her performances in Oskar Kokoschka's Hiob (1918), Ernst Toller's Transformation (1919), and Frank Wedekind's Franziska earned her popularity.[4]

In the 1920s, Gert premiered one of her more provocative works, titled "Pause". Performed in between reels at Berlin cinemas, it was intended to draw attention to inactivity, silence, serenity, and stillness amid all the movement and chaos in modern life. She came onstage and literally just stood there.[5] "It was so radical just to go on stage in the cinema and stand there and do nothing," said Wolfgang Mueller.[6] Gert began acting at the Munich Kammerspiele.[1] Also in the 1920s, Gert's other progressive performances included dancing a traffic accident, boxing, or dying. She was revolutionary and radical and never ceased to simultaneously shock and fascinate her audiences. When she danced an orgasm in Berlin in 1922, the audience called the police.[7]

During this time, she performed in the Schall und Rauch cabaret.[1][8] Gert also launched a tour of her own dances, with titles like Dance in Orange, Boxing, Circus, Japanese Grotesque, Death, and Whore.[1] In addition, she contributed articles for magazines like Die Weltbühne (The World Stage) and the Berliner Tageszeitung (Berline Daily News).[2]

By 1923, Gert focused her work more on film acting than live performance, performing with Andrews Engelmann, Arnold Korff, and others.[9] She performed in G.W. Pabst's Joyless Street in 1925, Diary of a Lost Girl in 1929, and The Threepenny Opera in 1931.[1][2] In the late 1920s, she returned to the stage with pieces emphasizing Tontänze (Sound Dances), which explored the relationship between movement and sound.[1]

Gert could be by turns grotesque, intense, mocking, pathetic or furious, performing with an anarchic intensity and artistic fearlessness which also recommended her to the Dadaists.[10] Valeska Gert analysed the limits of societal conventions and then expressed with her body the insights that she gained from her analyses.[7]

In 1933, Gert's Jewish heritage resulted in her being banned from the German stage. Her exile from Germany sent her to London for some time, where she worked both in theatre and film.[1] In London, she worked on the experimental short film Pett and Pott, which long stood as her last movie. While in London, she wed an English writer, Robin Hay Anderson,[11] her second marriage.[2]

In 1938, she emigrated to the United States, where she was cared for by a Jewish refugee community. She found work washing dishes and posing as a nude model.[2] This same year, she hired the 17-year-old Georg Kreisler as a rehearsal pianist to continue focus on cabaret work. By 1941, she had opened the Beggar Bar in New York. It was a cabaret/restaurant that was filled with mismatched furniture.[6] Julian Beck, Judith Malina,[1] and Jackson Pollock worked for her.[12] Tennessee Williams also worked for her for a short time as a busboy, but was fired for refusing to pool his tips.[12] Gert commented that his work was "so sloppy".[13]

By 1944, Gert had relocated to Provincetown, Massachusetts, where she opened Valeska's.[1] Here, she reunited with Tennessee Williams. She told him stories of hiring a 70-year-old midget named Mademoiselle Pumpernickel who became jealous whenever Gert went onstage. During this period, she was called to Provincetown court for throwing garbage out of her window and failing to pay a dance partner. She called upon Williams as a character witness, which he did with pleasure, despite her having fired him. He told incredulous friends that he "simply liked her".[12]

In 1947 she returned to Europe. After stays in Paris and Zurich, in 1949 she went to Blockaded Berlin, where she opened the cabaret Hexenküche (Witch's Kitchen) in 1948.[2] Following Hexenküche, she opened Ziegenstall (Goat Shed) on the island of Sylt.[1] In the 1960s, she made her comeback in film. In 1965, she had a role in Fellini's Juliet of the Spirits,[1] the success of which caused her to market herself to young German directors in the 1970s. During this period, she played in Rainer Werner Fassbinder's TV series Eight Hours Don't Make a Day and in Volker Schlöndorff's 1976 movie Coup de Grâce.[2]

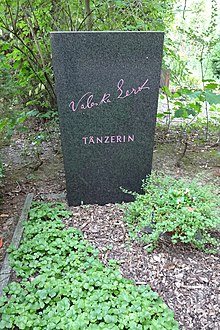

In 1978, Werner Herzog invited her to play the real estate broker Knock in his remake of Murnau's classic film Nosferatu. The contract was signed March 1 but she died just two weeks later before filming began. On 18 March 1978 neighbors and friends in Kampen, Germany, reported she had not been seen for four days. When her door was forced in the presence of police she was found dead. She is believed to have died on 16 March. She was 86 years old. In 2010, the art of Valeska Gert was presented at the Berlin Museum for Contemporary Art Hamburger Bahnhof, in the exhibition Pause. Bewegte Fragmente (Pause. Fragments in motion). The curators Wolfgang Müller from the art punk band Die Tödliche Doris (The Deadly Doris) and art historian An Paenhuysen included a video Baby showing Gert performing. Baby had been unknown until this show. It was recorded by Erich Mitzka in 1969.[citation needed]