| Human vulva | |

|---|---|

Vulvae of different women (pubic hair removed in some cases) (Genetic variation) | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Genital tubercle, urogenital folds |

| Artery | Internal pudendal artery |

| Vein | Internal pudendal veins |

| Nerve | Pudendal nerve |

| Lymph | Superficial inguinal lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | pudendum femininum |

| MeSH | D014844 |

| TA98 | A09.2.01.001 |

| TA2 | 3547 |

| FMA | 20462 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

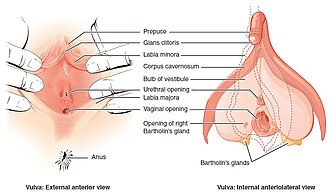

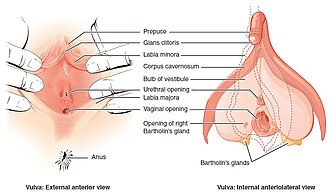

The vulva (from the Latin vulva, plural vulvae, see etymology) consists of the external genital organs of a woman. The external vulva is superficial to the internal vulva. The external vulva consists of the labia majora, mons pubis, labia minora, clitoris, bulb of vestibule, vulval vestibule, greater and lesser vestibular glands, external urethral orifice and the opening of the vagina (introitus) and the mons pubis.[1][2]

As the outer portal of the human uterus or womb, it protects its opening by a "double door": the labia majora (large lips) and the labia minora (small lips). The vagina is a self-cleaning organ, sustaining healthy microbial flora that flow from the inside out; the vulva needs only simple washing to assure good vulvovaginal health, without recourse to any internal cleansing.[citation needed]

Structure

External structures

The external structures of the vulva are::

- the mons pubis

- the labia, consisting of the labia majora and the labia minora

- the external portion of the clitoris, consisting of the clitoral glans and the clitoral hood

- the urinary meatus (opening of the urethra)

- the vaginal orifice (opening of the vagina)

- the hymen

- the anus[3][4][5]

- the vulval vestibule

- the pudendal cleft

- the frenulum labiorum pudendi or the fourchette

- the perineum

- the sebaceous glands on labia majora

- the vaginal glands:

- Bartholin's glands

- Paraurethral glands called Skene's glands

Internal structures

Lymphatic tissue

Vulvar tissues and organs are drained by the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.[2]

Muscle tissue

Pelvic floor muscles help to support the external and internal vulvar structures.[2]

Blood supply

Blood flow to the vulvar area is provided by the internal pudendal artery.[2]

The soft mound at the front of the vulva is formed by fatty tissue covering the pubic bone, and is called the mons pubis. The term mons pubis is Latin for "pubic mound" and it is gender-nonspecific. There is, however, a variant term that specifies gender: in human females, the mons pubis is often referred to as the mons veneris, Latin for "mound of Venus" or "mound of love". The mons pubis separates into two folds of skin called the labia majora, literally "major (or large) lips". The cleft between the labia majora is called the pudendal cleft, or cleft of Venus, and it contains and protects the other, more delicate structures of the vulva. The labia majora meet again at a flat area between the pudendal cleft and the anus called the perineum. The color of the outside skin of the labia majora is usually close to the overall skin color of the individual, although there is considerable variation. The inside skin and mucous membrane are often pink or brownish. After the onset of puberty, the mons pubis and the labia majora become covered by pubic hair. This hair sometimes extends to the inner thighs and perineum, but the density, texture, color, and extent of pubic hair coverage vary considerably, due to both individual variation and cultural practices of hair modification or removal.[citation needed]

The labia minora are two soft folds of skin within the labia majora. While labia minora translates as "minor (or small) lips", often the "minora" are of considerable size, and may protrude outside the "majora". Much of the variation among vulvas lies in the significant differences in the size, shape, and color of the labia minora.[citation needed]

The clitoris is located at the front of the vulva, where the labia minora meet. The visible portion of the clitoris is the clitoral glans. Typically, the clitoral glans is roughly the size and shape of a pea, although it can be significantly larger or smaller. The clitoral glans is highly sensitive, containing as many nerve endings as the analogous organ in males, the glans penis. The point where the labia minora attach to the clitoris is called the frenulum clitoridis. A prepuce, the clitoral hood, normally covers and protects the clitoris, however in women with particularly large clitorises or small prepuces, the clitoris may be partially or wholly exposed at all times. The clitoral hood is the female equivalent of the male foreskin. Often the clitoral hood is only partially hidden inside of the pudendal cleft.

The area between the labia minora is called the vulval vestibule, and it contains the vaginal and urethral openings. The urethral opening (meatus) is located below the clitoris and just in front of the vagina. This is where urine passes from the urinary bladder to be disposed of.[citation needed]

The opening of the vagina is located at the bottom of the vulval vestibule, toward the perineum. The term introitus is more technically correct than "opening", since the vagina is usually collapsed, with the opening closed, unless something is inserted. The introitus is sometimes partly covered by a membrane called the hymen. The hymen will rupture during the first episode of vigorous sex, and the blood produced by this rupture has been seen as a sign of virginity. However, the hymen may also rupture spontaneously during exercise (including horseback riding) or be stretched by normal activities such as use of tampons and menstrual cups, or be so minor as to be unnoticeable. In some rare cases, the hymen may completely cover the vaginal opening, requiring a surgical incision. Slightly below and to the left and right of the vaginal opening are two Bartholin glands which produce a waxy, pheromone-containing substance, the purpose of which is not yet fully known.[citation needed]

Development

Fetus

Vulva development occurs during several phases, chiefly during the fetal and pubertal periods of time.

During the first eight weeks of life, both male and female fetuses have the same rudimentary reproductive and sexual organs, and maternal hormones control their development. Male and female organs begin to become distinct when the fetus is able to begin producing its own hormones, although visible determination of the sex is difficult until after the twelfth week.

During the sixth week, the genital tubercle develops in front of the cloacal membrane. The tubercle contains a groove termed the urethral groove. The urogenital sinus (forerunner of the bladder) opens into this groove. On either side of the groove are the urogenital folds. Beside the tubercle are a pair of ridges called the labioscrotal swellings.

Beginning in the third month of development, the genital tubercle becomes the clitoris. The urogenital folds become the labia minora, and the labioscrotal swellings become the labia majora.

Childhood

At birth, the neonate's vulva (and breast tissue—see witch's milk) may be swollen or enlarged as a result of having been exposed, via the placenta, to her mother's increased levels of hormones. The clitoris is proportionally larger than it is likely to be later in life. Within a short period of time as these hormones wear off, the vulva will shrink in size.

From one year of age until the onset of puberty, the vulva does not undergo any change in appearance, other than growing in proportion with the rest of her body.

Puberty

The onset of puberty produces a number of changes. The structures of the vulva become proportionately larger and may become more pronounced. Coloration may change and pubic hair develops, first on the labia majora, and later spreading to the mons pubis, and sometimes the inner thighs and perineum.

In preadolescent girls, the vulva appears to be positioned further forward than in adults, showing a larger percentage of the labia majora and pudendal cleft when standing. During puberty the mons pubis enlarges, pushing the forward portion of the labia majora away from the pubic bone, and parallel to the ground (when standing). Variations in body fat levels affect the extent to which this occurs.

Childbirth

During childbirth, the vagina and vulva must stretch to accommodate the baby's head (approximately 9.5 cm (3.7 in)). This can result in tears in the vaginal opening, labia, and clitoris. An episiotomy (a preemptive surgical cutting of the perineum) is sometimes performed to control tearing, but is no longer considered appropriate as a routine procedure and has been shown to increase tearing or healing times rather than improve it in many cases. Perennial tearing or cutting does leave scar tissue.

Some other changes to the vagina and vulva that occur during pregnancy may become permanent.[citation needed]

Post-menopause

During menopause, hormone levels decrease, and as this process happens, reproductive tissues which are sensitive to these hormones shrink in size. The mons pubis, labia, and clitoris are reduced in size in post-menopause, although not usually to pre-puberty proportions.[citation needed]

Sexual homology

Most male and female sex organs originate from the same tissues during fetal development; this includes the vulva. The anatomy of the vulva is related to the anatomy of the male genitalia by a shared developmental biology. Organs that have a common developmental ancestry in this way are said to be homologous.

The clitoral glans is homologous to the glans penis in males, and the clitoral body and the clitoral crura are homologous to the corpora cavernosa of the penis. The labia majora, labia minora, and clitoral hood are homologous to the scrotum, shaft skin of the penis, and the foreskin, respectively. The vestibular bulbs beneath the skin of the labia minora are homologous to the corpus spongiosum, the tissue of the penis surrounding the urethra. The Bartholin's glands are homologous to the Cowper's glands in males.[citation needed]

Function and physiology

The vulva has a sexual function; these external organs are richly innervated and provide pleasure when properly stimulated. There are a number of different secretions associated with the vulva, including urine, sweat, menses, skin oils (sebum), Bartholin's and Skene's gland secretions, and vaginal wall secretions. These secretions contain a mix of chemicals, including pyridine, squalene, urea, acetic acid, lactic acid, complex alcohols, glycols, ketones, and aldehydes. During sexual arousal, vaginal lubrication increases. Smegma is a white substance formed from a combination of dead cells, skin oils, moisture and naturally occurring bacteria, that forms in mammalian genitalia. In females it collects around the clitoris and labial folds.[citation needed]

Some women produce aliphatic acids. These acids are a pungent class of chemicals which other primate species produce as sexual-olfactory signals. While there is some debate, researchers often refer to them as human pheromones. These acids are produced by natural bacteria resident on the skin. The acid content varies with the menstrual cycle, rising from one day after menstruation, and peaking mid-cycle, just before ovulation.[citation needed]

Sexual arousal

Sexual arousal results in a number of physical changes in the vulva. Vaginal lubrication begins first. The clitoris and labia minora increase in size. Increased vasocongestion in the vagina causes it to swell, decreasing the size of the vaginal opening by about 30%. The clitoris becomes increasingly erect, and the glans moves towards the pubic bone, becoming concealed by the hood. The labia minora increase considerably in thickness. The labia minora sometimes change considerably in color, going from pink to red in lighter skinned women who have not borne a child, or red to dark red in those that have. Immediately prior to the female orgasm, the clitoris becomes exceptionally engorged, causing the glans to appear to retract into the clitoral hood. Rhythmic muscle contractions occur in the outer third of the vagina, as well as the uterus and anus. Contractions become less intense and more randomly spaced as the orgasm continues. An orgasm may have as few as one or as many as 15 or more contractions, depending on its intensity. Orgasm may be accompanied by female ejaculation, causing liquid from either the Skene's gland or bladder to be expelled through the urethra. The pooled blood begins to dissipate, although at a much slower rate if an orgasm has not occurred. The vagina and vaginal opening return to their normal relaxed state, and the rest of the vulva returns to its normal size, position and color.[citation needed]

Clinical significance

Vulvar organs and tissues can become infected with bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoans and arthropods. Internal sexually transmitted infections may not be visible in the vulvar region, but these internal infections may cause symptoms and signs on the external vulvar region.

Vulvar sexually transmitted infections

Some lower reproductive tract infections, vaginal discharge and sexually transmitted infections of the upper reproductive tract will cause irritation, inflammation or discomfort when the discharge comes in contact with vulvar tissue.[6][7]

Bacterial infection

Examples of these include

- Chancroid (Haemophilus ducreyi)

- Granuloma inguinale or (Klebsiella granulomatis)

- Syphilis (Treponema pallidum)

Viral infection

- Herpes simplex (Herpes simplex virus 1, 2) skin and mucosal, transmissible with or without visible blisters

- HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus)—venereal fluids, semen, breast milk, blood

- HPV (Human Papillomavirus)—skin and mucosal contact. 'High risk' types of HPV cause almost all cervical cancers, as well as some anal, penile, and vulvar cancer. Some other types of HPV cause genital warts.

- Molluscum contagiosum (molluscum contagiosum virus MCV)—close contact

Fungal infection

- Candidiasis (yeast infection)

Protozoan

Arthropod infestation

- Crab louse, colloquially known as "crabs" or "pubic lice" (Pthirus pubis)

- Scabies (Sarcoptes scabiei)

Cancer

Many cancers, tumours and other malignancies can develop in vulvar structures.[2] Vulvar cancer may have signs and symptoms. These include:

- Itching, burn, or bleeding on the vulva that does not go away.

- Changes in the color of the skin of the vulva, so that it looks redder or whiter than is normal.

- Skin changes in the vulva, including what looks like a rash or warts.

- Sores, lumps, or ulcers on the vulva that do not go away.

- Pain in your pelvis, especially when you urinate or have sex.[8] If surgery is necessary, standard surgical and nursing procedures are conducted.[1]

Carcinomas

- adenocarcinoma

- basal cell carcinoma

- Bartholin gland carcinoma

- Merkel cell tumor

- squamous cell carcinoma

- transitional cell carcinoma

- verrucous carcinoma

- vulvar malignant melanoma

- vulvar Paget disease

Sarcomas

- leiomyosoarcoma

- malignant fibrous histiocytoma

- epithelial sarcoma

- malignant rhabdoid tumor

Other

- malignant schwannoma

- metastiatic cancers to the vulva

- yolk sac tumors[2]

- Crohn's disease of the vulva[9]

- skin dryness

- hormone fluctuations

- atopic and irritant dermatitis

- psoriasis

- lichen sclerosus

- infectious vulvovaginitis

- atro-phic vulvovaginitis

- lichen simplex chronicus

- neuropathic itch

- pemphigoid gestationis

- polymorphiceruption of pregnancy

- intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

- atopic eruption of pregnancy[7]

Plastic surgery

Genitoplasty can be done to repair, restore or alter vulvar tissues. Vulvar surgeries that are sometimes performed to change the appearance of the external structures are vaginoplasty, genitoplasty, and labioblasty.

Elective vulvar surgery has been criticized by clinicians. Recommendations for informing women of the risks included the lack of data supporting these procedures and the potential associated risks such as infection, altered sensation, dyspareunia, adhesions, and scarring have been promulgated by professional societies.[10][11][12][12] The World Health Organization describes any medically unnecessary surgery to the vaginal tissue and organs as Female genital mutilation.[13]

Complications

Pubic shaving can result in cuts to the vulva and clitoris, ingrown hairs, pseudofolliculitis barbae (razor bumps) and folliculitis.[14] Shaving of the vulvar region increases the risk of contracting the sexually transmitted viral infection, molluscum contagiosum.[15]

The vulvar region is at risk for trauma during labor and delivery.[16] No advantages have been demonstrated in the shaving of vulvar hair prior to labor. Rates of complications remain the same between women who were shaved and those unshaven.[17][18]

Society and culture

Many cultures have no or few taboos on exposure of the breasts, but the vulva and pubic triangle are always the first areas to be covered. Saartjie Baartman, the so-called "Hottentot Venus" who was exhibited in London at the beginning of the nineteenth century, was paid to display her large buttocks, but she never revealed her vulva. Khoisan women were said to have elongated labia, leading to questions about, and requests to exhibit, their sinus pudoris, "curtain of shame", or tablier (the French word for "apron"). To quote Stephen Jay Gould, "The labia minora, or inner lips, of the ordinary female genitalia are greatly enlarged in Khoi-San women, and may hang down three or four inches below the vagina when women stand, thus giving the impression of a separate and enveloping curtain of skin".[19] Baartman never allowed this trait to be exhibited while she was alive.[20]

In some cultures, including modern Western culture, women have shaved or otherwise depilated part or all of the vulva. When high-cut swimsuits became fashionable, women who wished to wear them would shave the sides of their pubic triangles, to avoid exhibiting pubic hair. Other women relish the beauty of seeing their vulva with hair, or completely hairless, and find one or the other more comfortable. Depilation of the vulva is a fairly recent phenomenon in the United States, Canada, and Western Europe, but has been prevalent, usually in the form of waxing, in many Eastern European and Middle Eastern cultures for centuries, usually due to the idea that it may be more hygienic, or originating in prostitution and pornography. Shaving may include all or nearly all of the hair. Some styles retain a small amount of hair on either side of the labia or a strip directly above and in line with the pudendal cleft.

Since the early days of Islam, Muslim women and men have followed a tradition to "pluck the armpit hairs and shave the pubic hairs". This is a preferred practice rather than an obligation, and could be carried out by shaving, waxing, cutting, clipping, or any other method. This is a regular practice that is considered in some more devout Muslim cultures as a form of worship, not a shameful practice, while in other less devout regions it is a practice for the purpose of good hygiene. (See Islamic hygienical jurisprudence.) The reasons behind removing this hair could also be applied to the hair on the scrotum and around the anus, because the purpose is to be completely clean and pure and keep away from anything that may cause dirt and impurities.[21]

Several forms of genital piercings can be done in the female genital area. Piercings are usually performed for aesthetic purposes, but some forms like the clitoral hood piercing might also enhance pleasure during sexual intercourse. Though they are common in traditional cultures, intimate piercings are a fairly recent trend in western culture.[22][23][24]

Altering the female genitalia

The most prevalent form of genital alteration in some countries is female genital mutilation (FGM): removal of any part of the female genitalia for cultural, religious or other non-medical reasons. This practice is highly controversial as it is often done to non-consenting minors and for debatable (often misogynistic) reasons. An estimated 100 to 140 million girls and women in Africa and Asia have experienced some form of FGM.[25]

Female genital surgery includes laser resurfacing of the labia to remove wrinkles, labiaplasty (reducing the size of the labia) and vaginal tightening. Some have likened labiaplasty to FGM.[26]

In September 2007, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued a committee opinion on these and other female genital surgeries, including "vaginal rejuvenation", "designer vaginoplasty", "revirgination", and "G-spot amplification". This opinion states that the safety of these procedures has not been documented. ACOG recommends that women seeking these surgeries need to be informed about the lack of data supporting these procedures and the potential associated risks such as infection, altered sensation, dyspareunia, adhesions, and scarring.[10]

With the growing popularity of female cosmetic genital surgeries, the practice increasingly draws criticism from an opposition movement of cyberfeminist activist groups and platforms, the so-called labia pride movement. The major point of contention is that heavy advertising for these procedures, in combination with a lack of public education, fosters body insecurities in women with larger labia in spite of the fact that there is normal and pronounced individual variation in the size of labia. The preference for smaller labia is a matter of fashion fad and is without clinical or functional significance.[27][28]

Etymology

The word vulva was taken from the Medieval Latin word volva or vulva ("womb, female genitals"), probably from the Old Latin volvere ("to roll"; lit. "wrapper").[29]

Alternative terms

As with nearly any aspect of the human body involved in sexual or excretory functions, there are many slang words for the vulva.[30] "Cunt", a medieval word for the vulva and once the standard term, has become in its literal sense a vulgarism, and in other uses one of the strongest abusive obscenities in English-speaking cultures.

Depictions of vulvae

Some cultures have tended to view the vulva as something shameful that should be hidden. For example, the term pudendum, which denotes the external genitalia, literally means "shameful thing".

Other cultures have long celebrated and even worshipped the vulva. Some Hindu sects revere it under the name yoni, and texts seem to indicate a similar attitude in some ancient Middle Eastern religions. As an aspect of Goddess worship such reverence may be part of modern Neopagan beliefs, and may be indicated in paleolithic artworks, dubbed "Old Europe" by archaeologist Marija Gimbutas. Ancient Greek women kept their vulva hairless so as to display their beauty.[citation needed]

-

Origin of the world, Oil painting by Gustave Courbet

-

Possible Rupestrian depictions of vulvae, paleolithic

-

Possible stylised vulva stone, paleolithic

-

Sheela na gig, figurative sculpture with an exaggerated vulva.

-

Attic red-figure lid. Three female organs and a winged phallus.

Slang

There are numerous slang words, euphemisms and synonyoms for the vulva in English and in other languages. See WikiSaurus:vulva for a list of slang words for vulva.

Art

- L'Origine du monde, the first realistic painting of a vulva in Western art

- Sheela na Gig, ancient and medieval European carvings

- Yoni, Sanskrit depictions

References

- ^ a b Rosdahl, Caroline (2012). Textbook of basic nursing. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9781605477725.

- ^ a b c d e f Hoffman, Barbara (2012). Williams gynecology. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 9780071716727.

- ^ Graaff, Kent (1989). Concepts of human anatomy and physiology. Dubuque, Iowa: Wm. C. Brown Publishers. ISBN 0697056759.

- ^ Baggish, Michael (2016). Atlas of pelvic anatomy and gynecologic surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. ISBN 9780323225526.

- ^ Black, Martin (2008). Obstetric and gynecologic dermatology. Edinburgh: Mosby/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7234-3445-0.

- ^ Mastromarino, Paola; Vitali, Beatrice; Mosca, Luciana (2013). "Bacterial vaginosis: a review on clinical trials with probiotics" (PDF). New Microbiologica. 36: 229–238. PMID 23912864.

- ^ a b Rimoin, Lauren P.; Kwatra, Shawn G.; Yosipovitch, Gil (2013). "Female-specific pruritus from childhood to postmenopause: clinical features, hormonal factors, and treatment considerations". Dermatologic Therapy. 26 (2): 157–167. doi:10.1111/dth.12034. ISSN 1396-0296.

- ^ "What Are the Symptoms of Vaginal and Vulvar Cancers?". CDC. 13 March 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Barret, Maximilien; de Parades, Vincent; Battistella, Maxime; Sokol, Harry; Lemarchand, Nicolas; Marteau, Philippe (2014). "Crohn's disease of the vulva". Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 8 (7): 563–570. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2013.10.009. ISSN 1873-9946.

- ^ a b American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2007). "Vaginal "Rejuvenation" and Cosmetic Vaginal Procedures" (PDF): 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2008.

((cite journal)): Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bourke, Emily (12 November 2009). "Designer vagina craze worries doctors". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ a b Liao, Lih Mei; Sarah M Creighton (24 May 2007). "Requests for cosmetic genitoplasty: how should healthcare providers respond?". BMJ. 334 (7603). British Medical Journal: 1090–1092. doi:10.1136/bmj.39206.422269.BE. PMC 1877941. PMID 17525451. Retrieved 3 March 2016. Cite error: The named reference "bmj" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Female genital mutilation". World Health Organization. 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ "Pubic Hair Removal - Shaving". Palo Alto Medical Foundation. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Risk Factors - Molluscum Contagiosum". CDC. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ Dudley, Lynn M; Kettle, Christine; Ismail, Khaled MK; Dudley, Lynn M (2013). "Secondary suturing compared to non-suturing for broken down perineal wounds following childbirth". doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008977.pub2.

((cite journal)): Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Basevi, Vittorio; Lavender, Tina; Basevi, Vittorio (2014). "Routine perineal shaving on admission in labour". doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001236.pub2.

((cite journal)): Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Lefebvre, A.; Saliou, P.; Lucet, J.C.; Mimoz, O.; Keita-Perse, O.; Grandbastien, B.; Bruyère, F.; Boisrenoult, P.; Lepelletier, D.; Aho-Glélé, L.S. (2015). "Preoperative hair removal and surgical site infections: network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Journal of Hospital Infection. 91 (2): 100–108. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2015.06.020. ISSN 0195-6701.

- ^ Gould, 1985

- ^ (Strother 1999)

- ^ According to Al-Munajjid, Sheikh Muhammad Saleh (Released 27 July 2004). "Islam Ruling on Shaving the Pubic Hair, Scrotum and Around the Anus".

- ^ "''Can selfish lovers ever give as good as they get? Plus, the perks of piercings and how to get her to hurry up already''". MSNBC. 4 December 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Vaughn S. Millner et al. (2005): ''First glimpse of the functional benefits of clitoral hood piercings'',American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Volume 193, Issue 3, Pages 675-676". Ajog.org. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "VCH Piercings, by Elayne Angel, Seite 16-17, The Official Newsletter of The Association of Professional Piercers" (PDF). Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Female genital mutilation". World Health Organization (WHO). February 2010.

- ^ Cormier, Zoe (Fall 2005). "Making the Cut". Shameless. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

((cite news)): Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Clark-Flory, Tracy (17 February 2013). "The "labia pride" movement: Rebelling against the porn aesthetic, women are taking to the Internet to sing the praises of "endowed" women". Salon.com. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

((cite news)): Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Sourdès, Lucile (21 February 2013). "Révolution vulvienne: Contre l'image de la vulve parfaite, elles se rebellent sur Internet". Rue89. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

((cite news)): Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ For slang terms for the vulva, see WikiSaurus:female genitalia — the WikiSaurus list of synonyms and slang words for female genitalia in many languages.

External links

Media related to Vulvas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Vulvas at Wikimedia Commons Media related to Vulva symbols at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Vulva symbols at Wikimedia Commons- 'V' is for vulva, not just vagina by Harriet Lerner discussing common misuse of the word "vagina"

- Pink Parts – "Walk through" of female sexual anatomy by sex activist and educator Heather Corinna (illustrations; no explicit photos)

| Internal |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Blood supply | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Other | |