| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

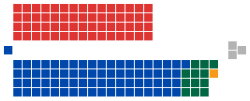

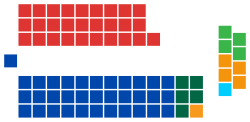

All 150 seats in the House of Representatives 76 seats were needed for a majority in the House 40 (of the 76) seats in the Senate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered | 13,098,461 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 12,354,983 (94.32%) ( | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

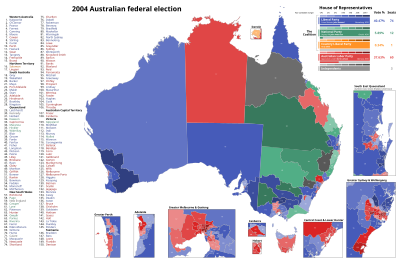

Results by division for the House of Representatives, shaded by winning party's margin of victory. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2004 Australian federal election |

|---|

| National results |

| State and territory results |

|

|

The 2004 Australian federal election was held in Australia on 9 October 2004. All 150 seats in the House of Representatives and 40 seats in the 76-member Senate were up for election. The incumbent Liberal Party of Australia led by Prime Minister of Australia John Howard and coalition partner the National Party of Australia led by John Anderson defeated the opposition Australian Labor Party led by Mark Latham.

Until 2019, this was the most recent federal election in which the leader of the winning party would complete a full term of Parliament as Prime Minister. Also until, 2022 this was the most recent federal election in which both leaders are from the same city area. Future Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull entered Parliament in this election.

In the wake of the 2002 Bali Bombings and the 2001 World Trade Center attacks, the Howard government along with the Blair and Bush governments, initiated combat operations in Afghanistan and an alliance for invading Iraq, these issues divided Labor voters[citation needed] who were disproportionately anti-war,[citation needed] flipping those votes from Labor and to the Greens.[citation needed] The second issue was the ongoing and continued worsening of the Millennium Drought continued to bolster support for the Nationals water management policies of the Murray-Darling river system,[citation needed] diverting focus away from rural and inner-city community water supplies and focusing on Regional and Farmland water supplies.

The Prime Minister, John Howard, announced the election at a press conference in Canberra on 29 August, after meeting the Governor-General, Major General Michael Jeffery, at Government House.

John Howard told the press conference that the election would be about trust.[citation needed] "Who do you trust to keep the economy strong and protect family living standards?" he asked "Who do you trust to keep interest rates low? Who do you trust to lead the fight on Australia's behalf against international terrorism?"[citation needed]

Howard, who turned 64 in July, declined to answer questions about whether he would serve a full three-year term if his government was re-elected. "I will serve as long as my party wants me to," he said.[1]

At a press conference in Sydney half an hour after Howard's announcement, Opposition Leader Mark Latham welcomed the election, saying the Howard government had been in power too long. He said the main issue would be truth in government. "We've had too much dishonesty from the Howard Government", he said. "The election is about trust. The Government has been dishonest for too long."[2]

The campaign began with Labor leading in all published national opinion polls.[citation needed] On 31 August, Newspoll published in The Australian newspaper gave Labor a lead of 52% to 48% nationwide, which would translate into a comfortable win for Labor in terms of seats. Most commentators,[who?] however, expected the election to be very close, pointing out that Labor was also ahead in the polls at the comparable point of the 1998 election, which Howard won.[citation needed] Howard had also consistently out-polled Latham as preferred Prime Minister by an average of 11.7 percentage points in polls taken this year.[3]

After the first week of campaigning, a Newspoll conducted for News Corporation newspapers indicated that the Coalition held a lead on a two-party-preferred basis of 52% to 48% in the government's 12 most marginal held seats.[citation needed] To secure government in its own right, Labor needed to win twelve more seats than in the 2001 election.[citation needed] In the same poll, John Howard increased his lead over Mark Latham as preferred Prime Minister by four points.[citation needed] The Taverner Research poll conducted for The Sun-Herald newspaper revealed that younger voters were more likely to support Labor, with 41% of those aged 18 to 24 supporting Labor, compared with 36% who support the Coalition.[citation needed]

On 9 September, during the second week of campaigning the election was rocked by a terrorist attack on the Australian embassy in Jakarta, Indonesia.[citation needed] John Howard expressed his "utter dismay at this event" and dispatched Foreign Minister Alexander Downer to Jakarta to assist in the investigation.[citation needed] Mark Latham committed the Labor party's "full support to all efforts by the Australian and Indonesian governments to ensure that happens".[citation needed] The parties reached an agreement that campaigning would cease for 10 September out of respect for the victims of this attack and that this would be in addition to the cessation of campaigning already agreed upon for 11 September in remembrance of the terrorist attacks in 2001.

A debate between John Howard and Mark Latham was televised commercial-free on the Nine Network at 7:30pm on Sunday 12 September. In a change from previous election debates, which involved a single moderator, the leaders were questioned by a five-member panel representing each of the major media groups in Australia. There was a representative from commercial television (Laurie Oakes), the ABC (Jim Middleton), News Limited (Malcolm Farr), John Fairfax Holdings (Michelle Grattan) and radio (Neil Mitchell). After an opening address, Howard and Latham responded to questions posed by the panel and had the opportunity to make a closing statement. The Nine Network permitted other television organisations to transmit the feed, but only the ABC chose to.[citation needed]

The debate was followed (only on the Nine Network) by an analysis of the leaders' performance by the "worm". The worm works by analysing the approval or disapproval of a select group of undecided voters to each statement that a leader makes. Throughout the debate, according to the worm, Latham performed strongly and Howard performed poorly.[citation needed] A final poll of the focus group found that 67% of the focus group believed that Latham won the debate and that 33% of the focus group believed that Howard won.[citation needed] Major media outlets generally agreed that Latham had won the debate, although they pointed out that with no further debates scheduled and nearly four weeks of the campaign remaining, Latham's gain in the momentum from the debate was unlikely to be decisive.[citation needed] Political commentators[who?] noted that the 2001 election debate, between Howard and then opposition leader Kim Beazley, gave the same worm results yet Labor still lost that election.[citation needed]

By the midpoint of the campaign, after Labor had released its policies on taxation and education, polls showed that the election was still too close to call. The Newspoll in The Australian, showed (21 September) Labor leading with 52.5% of the two-party-preferred vote. The ACNielsen poll published in The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age showed the Coalition ahead on 52%. The Morgan poll, which has a poor recent record of predicting federal elections, showed Labor ahead with 53% on the weekend of 18–19 September. A Galaxy Poll in the Melbourne Herald Sun showed the Coalition ahead with 51%, but showed Labor gaining ground.

Despite Latham's strong performance in the debate, most political commentators[who?] argued that he had not gained a clear advantage over Howard. They pointed to anomalies in Labor's tax policy and the controversy surrounding Labor's policy of reducing government funding to some non-government schools as issues which Howard was successfully exploiting.[citation needed]

John Howard and John Anderson launched the Coalition election campaign at a joint function in Brisbane on 26 September. Howard's policy speech can be read at the Liberal Party website.[4] Anderson's policy speech can be read at the National Party website.[5]

Mark Latham's policy speech was delivered, also in Brisbane, on 29 September.

During the fourth week of the campaign contradictory polls continued to appear. The ACNielsen poll published in The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age on 25 September showed the Coalition ahead with 54%, which would translate into a large majority for the government. The Newspoll in The Australian on 28 September showed Labor ahead with 52%, which would give Labor a comfortable majority.

In the last days of the campaign the environment policies regarding the logging of Tasmania's old-growth forests were released by both major parties, but too late for the Greens to adjust their preference flows on how-to-vote cards in most electorates as the majority were already printed.[citation needed] In the game of "cat and mouse" on Tasmanian forest policy between Mark Latham and John Howard, Latham eventually lost out when Dick Adams (Labor member for the Tasmanian seat of Lyons), Tasmanian Labor Premier Paul Lennon and CFMEU's Tasmanian secretary Scott McLean all attacked Latham's forest policy.[citation needed] At a timber workers' rally on the day Labor's forestry policy was announced, Scott McLean asked those gathered to pass a resolution of no confidence in Mr Latham's ability to lead the country.[6] Michael O'Connor, assistant national secretary of the CFMEU said the Coalition's forest policy represented a much better deal for his members than Labor's policy.[7] Australian Labor Party national president Carmen Lawrence later said that "Labor has only itself to blame for the backlash over its forestry policy" and that it was a strategic mistake to release the policy so late in the election campaign. She stated that she was disappointed in criticism from within the ALP and union movement, and that the party did not leave itself enough time to sell the package.[8]

Treasury and the Department of Finance reported on the validity of Labor's costings of their promises. They claimed to identify a different flaw to that identified by Liberal Treasurer Costello, but overall Labor was satisfied with the report.[citation needed]

On the morning of 8 October, the day before the election, a television crew filmed Latham and Howard shaking hands as they crossed paths outside an Australian Broadcasting Corporation radio studio in Sydney. The footage showed Latham appearing to draw Howard towards him and tower over his shorter opponent. The incident received wide media coverage and, while Latham claimed to have been attempting to get revenge for Howard squeezing his wife's hand too hard at a press function, it was variously reported as being "aggressive", "bullying" and "intimidating" on the part of Latham.[citation needed] The Liberal Party campaign director, Brian Loughnane, later said this incident generated more feedback to Liberal headquarters than anything else during the six-week campaign, and that it "brought together all the doubts and hesitations that people had about Mark Latham".[citation needed] Latham disputes the impact of this incident, however, having described it as a "Tory gee-up: we got close to each other, sure, but otherwise it was a regulation man's handshake. It's silly to say it cost us votes – my numbers spiked in the last night of our polling." (Latham Diaries, p. 369) According to Latham's account of events, Latham came in close to Howard for the handshake to prevent Howard shaking with his arm rather than his wrist.

The final opinion polls continued to be somewhat contradictory, with Newspoll showing a 50–50 tie and the Fairfax papers reporting 54–46 to the Coalition. Most Australian major daily newspaper editorials backed a return of the Howard government, with the notable exceptions of The Sydney Morning Herald, which backed neither party, and The Canberra Times, which backed Labor.[9]

As in all Australian elections, the flow of preferences from minor parties can be crucial in determining the outcome. The close of nominations was followed by a period of bargaining among the parties. Howard made a pitch for the preferences of the Australian Greens by appearing to offer concessions on the issue of logging in old-growth forests in Tasmania, and the Coalition directed its preferences to the Greens ahead of Labor in the Senate, but the Greens nevertheless decided to allocate preferences to Labor in most electorates. In exchange, Labor agreed to direct its preferences in the Senate to the Greens ahead of the Democrats (but critically, not ahead of other minor parties), increasing the chances that the Greens would displace Australian Democrats Senators in New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia.

The Democrats in turn did a preference deal with the Family First Party, which angered some Democrats supporters who viewed Family First's policies as incompatible with the Democrats'.

In Victoria, Family First, the Christian Democrats and the DLP allocated their senate preferences to Labor, to help ensure the re-election of the number three Labor Senate candidate, Jacinta Collins, a Catholic who has conservative views on some social issues such as abortion. In exchange, Labor gave its Senate preferences in Victoria to Family First ahead of the Greens, expecting Family First to be eliminated before these preferences were distributed. In the event, however, Labor and Democrat preferences helped Family First's Steve Fielding beat the Greens' David Risstrom to win the last Victorian Senate seat and become Family First's first federal parliamentarian.[10] This outcome generated some controversy and highlighted a lack of transparency in preference deals. Family First were elected in Victoria after receiving 1.88% of the vote, even though the Greens had the largest minor party share of the vote with 8.8%. In Australia, 95% of voters vote "above the line" in the Senate.[11] Many "above the line" voters do not access preference allocation listings, although they are available in polling booths and on the AEC website, so they are therefore unaware of where their vote may go. The result was one Family First, three Liberal and two Labor Senators elected in Victoria.

In Tasmania, Family First and the Democrats also directed their Senate preferences to Labor, apparently to preclude the possibility of the Liberals winning a majority in the Senate and thus reducing the influence of the minor parties. The Australian Greens' Christine Milne appeared at risk of losing her Senate seat to a Family First candidate shortly after election night, despite nearly obtaining the full required quota of primary votes. However, strong performance on postal and prepoll votes improved Milne's position. It was only the high incidence of "below the line" voting in Tasmania that negated the effect of the preference swap deal between Labor and Family First.[12] The result was one Green, three Liberal and two Labor Senators elected in Tasmania.

In New South Wales, Democrat preferences flowing to Labor rather than the Greens were instrumental in Labor's winning of the last Senate seat. Had Democrat preferences flown to the Greens rather than Liberals for Forests and the Christian Democrats, then the final vacancy would have been won by the Greens' John Kaye. The scale of Glenn Druery's (of the Liberals for Forests party) preference deals was revealed by the large number of ticket votes distributed when he was eliminated from the count. He gained preferences from a wide range of minor parties such as the Ex-Service Service and Veterans Party, the Outdoor Recreation Party, and the Non-Custodial Parents Party. Liberals for Forests also gained the preferences of two leftish parties – the Progressive Labour Party and the HEMP Party. When Druery was eventually excluded, these preferences flowed to the Greens, but the Greens would rather have received the preferences earlier in the count. In the end, three Liberal/National Senators and three Labor Senators were elected in New South Wales.[13]

In Western Australia, the Greens' Rachel Siewert was elected to the final vacancy after the final Labor candidate was excluded. This was a gain for the Greens at the expense of the Democrats Brian Greig. While the Democrats had done a preference swap with Family First, the deal in Western Australia did not include the Christian Democrats. As a result, when the Australian Democrats were excluded from the count, their preferences flowed to the Greens, putting them on track for the final vacancy.[14] The result was one Green, three Liberal and two Labor Senators elected in Western Australia.

In South Australia, the Australian Democrats negotiated a crucial preference swap with Family First that prevented the Greens winning the final vacancy. If the Democrats had polled better, they would have collected Family First and Liberal preferences and won the final vacancy. Former Democrat Leader Meg Lees also contested the Senate in South Australia, but was eliminated late in the count. However, Lees did have some impact on the outcome, as there were large numbers of below the line preferences for both the Progressive Alliance (as well as One Nation) which were widely spread rather than flowing to the Democrats. When the Democrats were excluded, preferences flowed to Family First which prevented the Greens' Brian Noone passing the third Labor candidate. This resulted in a seat that could otherwise have been won by the Greens instead being won by Labor on Green preferences. The flow of One Nation preferences to Labor made it impossible for either Family First or the Liberal Party to win the final vacancy. Labor's Dana Wortley was elected to the final vacancy.[15] The result in South Australia was split 3 Liberal, 3 Labor.

In Queensland, Pauline Hanson attracted 38,000 below the line votes and pulled away from One Nation. Preferences from the Fishing Party kept the National Party's Barnaby Joyce ahead of Family First and Pauline Hanson. Joyce then unexpectedly won the fifth vacancy ahead of the Liberal Party. The sixth and last vacancy was then won by Liberal Russell Trood.[16] The outcome was 1 National, 3 Liberals and 2 Labor.

The election of both Barnaby Joyce and Russell Trood to the Senate in Queensland resulted in the Coalition gaining control of the Senate and was confirmed by the National Party's Senate Leader Ron Boswell's in a televised telephone call to Prime Minister John Howard.[17] This result was not widely predicted prior to the election.

Despite constant media attention on preference deals, and a widely held belief that the two party preferred result for the election would be close, the Newspoll figures during the three months prior to the election showed little alteration in the first preference margin between the parties, nor was there any evidence of any voter volatility. The figures suggested, then, that as the Coalition's first preference vote was healthy, the most likely result was a Government victory. This was born out in the election results when the Liberal first preference vote of 40.5 per cent was 3.4 percentage points higher than in 2001, while Labor's first-preference vote of 37.6 per cent was its lowest since the elections of 1931 and 1934.[18] Preference flows from minor parties are much more likely to affect an election outcome when the two major parties are close. The collapse of Labor's primary vote therefore negated this effect, even though 61 out of 150 House of Representatives seats were decided on preferences.[19]

The national outcome of minor party preference distributions (in order of number primary votes received) is summarised in the following table:[20]

| Minor party | Total votes | % to Liberal/National Coalition | % to Labor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democratic Party | 72,241 | 74.63 | 25.37 |

| Citizens Electoral Council | 42,349 | 47.83 | 52.17 |

| Socialist Alliance | 14,155 | 25.55 | 74.45 |

| New Country Party | 9,439 | 59.16 | 40.84 |

| Liberals for Forests | 8,165 | 60.18 | 39.82 |

| No GST | 7,802 | 38.11 | 61.89 |

| Ex-Service, Service and Veterans Party | 4,369 | 52.69 | 47.31 |

| Progressive Labour Party | 3,775 | 19.36 | 80.64 |

| Outdoor Recreation Party | 3,505 | 44.37 | 55.63 |

| Save the ADI Site Party | 3,490 | 33.12 | 66.88 |

| The Great Australians | 2,824 | 61.47 | 38.53 |

| The Fishing Party | 2,516 | 45.15 | 54.85 |

| Lower Excise Fuel and Beer Party | 2,007 | 52.96 | 47.04 |

| Democratic Labor Party | 1,372 | 58.53 | 41.47 |

| Non-Custodial Parents Party | 1,132 | 26.86 | 73.14 |

| HEMP | 787 | 41.93 | 58.07 |

| Nuclear Disarmament Party | 341 | 20.82 | 79.18 |

| Aged and Disability Pensioners Party | 285 | 45.96 | 54.04 |

Dates for financial disclosure for the 2004 Federal election were specified by the Australian Electoral Commission. Broadcasters and publishers had to lodge their returns by 6 December, while candidates and Senate groups needed to lodge by 24 January 2005. This information was made available for public scrutiny on 28 March 2005.

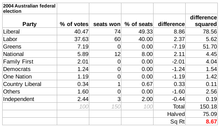

| Party | Votes | % | Swing | Seats | Change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | 4,741,458 | 40.47 | +3.39 | 74 | |||

| National | 690,275 | 5.89 | +0.28 | 12 | |||

| Country Liberal | 39,855 | 0.34 | +0.02 | 1 | |||

| Liberal–National coalition | 5,471,588 | 46.71 | +3.79 | 87 | |||

| Labor | 4,408,820 | 37.63 | –0.21 | 60 | |||

| Greens | 841,734 | 7.19 | +2.23 | 0 | |||

| Family First | 235,315 | 2.01 | +2.01 | ||||

| Democrats | 144,832 | 1.24 | –4.17 | ||||

| One Nation | 139,956 | 1.19 | –3.15 | ||||

| Others | 472,590 | 4.03 | –0.06 | 3 [b] | |||

| Total | 11,714,835 | 150 | |||||

| Two-party-preferred vote | |||||||

| Coalition | Win | 52.74 | +1.79 | 87 | |||

| Labor | 47.26 | –1.79 | 60 | ||||

| Invalid/blank votes | 639,851 | 5.18 | +0.36 | ||||

| Registered voters/turnout | 13,098,461 | 94.32 | |||||

| Source: Commonwealth Election 2004 | |||||||

| Party | Votes | % | ± | Seats | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seats won |

Not up |

New total |

Seat change | ||||||

| Liberal/National Coalition | |||||||||

| Liberal/National joint ticket | 3,074,952 | 25.72 | +1.85 | 6 | 6 | 12 | |||

| Liberal | 2,109,948 | 17.65 | +1.96 | 13 | 11 | 24 | |||

| National | 163,261 | 1.37 | −0.55 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Country Liberal (NT) | 41,923 | 0.35 | +0.00 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Coalition total | 5,390,084 | 45.09 | +3.26 | 21 | 18 | 39 | |||

| Labor | 4,186,715 | 35.02 | +0.70 | 16 | 12 | 28 | |||

| Greens | 916,431 | 7.67 | +2.73 | 2 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Democrats | 250,373 | 2.09 | -5.16 | 0 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Family First | 210,567 | 1.76 | +1.76 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| One Nation | 206,455 | 1.73 | -3.81 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Others | 792,994 | 6.65 | +1.31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Total | 11,953,649 | 100.00 | – | 40 | 36 | 76 | |||

| Invalid/blank votes | 466,370 | 3.75 | −0.14 | – | – | – | – | ||

| Registered voters/turnout | 12,420,019 | 94.82 | -0.38 | – | – | – | – | ||

| Source: Upper house results: AEC | |||||||||

|

For all seats, see 2006 Mackerras federal election pendulum. |

In the House of Representatives, the Coalition won eight seats from Labor: Bass (Tas), Bonner (Qld), Braddon (Tas), Greenway (NSW), Hasluck (WA), Kingston (SA), Stirling (WA) and Wakefield (SA). Labor won four seats from the Coalition: Adelaide (SA), Hindmarsh (SA), Parramatta (NSW) and Richmond (NSW). The Coalition thus had a net gain of four seats. The redistribution had also delivered them McMillan (Vic), formerly held by Christian Zahra of Labor and won by Liberal Russell Broadbent; and Bowman (Qld), formerly held by Labor's Con Sciacca and won by Liberal Andrew Laming. Labor, meanwhile, received the new seat of Bonner (Qld) and the redistributed Wakefield (SA), both of which were lost to the Liberal Party. The Labor Party regained the seat of Cunningham, which had been lost to the Greens in a by-election in 2002.

The Coalition parties won 46.7% of the primary vote, a gain of 3.7% over the 2001 election. The opposition Australian Labor Party polled 37.6%, a loss of 0.2 percentage points. The Australian Greens emerged as the most prominent minor party, polling 7.2%, a gain of 2.2 points. Both the Australian Democrats and One Nation had their vote greatly reduced. After a notional distribution of preferences, the Australian Electoral Commission estimated that the Coalition had polled 52.74% of the two-party-preferred vote, a gain of 1.7 points from 2001.

The Liberal Party won 74 seats, the National Party 12 seats and the Country Liberal Party (the Northern Territory branch of the Liberal Party) one seat, against the Labor opposition's 60 seats. Three independent members were re-elected. The Coalition also won 39 seats in the 76-member Senate, making the Howard government the first government to have a majority in the Senate since 1981. The size of the government's win was unexpected: few commentators[who?] had predicted that the coalition would actually increase its majority in the House of Representatives, and almost none had foreseen its gaining a majority in the Senate.[citation needed] Even Howard had described that feat as "a big ask".[citation needed]

The election result was a triumph for Howard, who in December 2004 became Australia's second-longest serving Prime Minister, and who saw the election result as a vindication of his policies, particularly his decision to join in the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The results were a setback for the Labor leader, Mark Latham, and contributed to his resignation in January 2005 after assuming the leadership from Simon Crean in 2003.[citation needed] The defeat made Labor's task more difficult: a provisional pendulum for the House of Representatives,[24] showed that Labor would need to win 16 seats to win the following election. However, Kim Beazley said that the accession of Latham to the ALP leadership, in December 2003, had rescued the party from a much heavier defeat.[25] Beazley stated that polling a year before the election indicated that the ALP would lose "25–30 seats" in the House of Representatives. Instead the party lost a net four seats in the House, a swing of 0.21 percentage points. There was also a 1.1-point swing to the ALP in the Senate. The Coalition gaining control of the Senate was enabled by a collapse in first preferences for the Australian Democrats and One Nation.

Members and Senators defeated in the election include Larry Anthony, the National Party Minister for Children and Youth Affairs, defeated in Richmond, New South Wales; former Labor minister Con Sciacca, defeated in Bonner, Queensland; Liberal Parliamentary Secretaries Trish Worth (Adelaide, South Australia) and Ross Cameron (Parramatta, New South Wales); and Democrat Senators Aden Ridgeway (the only indigenous member of the outgoing Parliament), Brian Greig and John Cherry. Liberal Senator John Tierney (New South Wales), who was dropped to number four on the Coalition Senate ticket, was also defeated.

Celebrity candidates Peter Garrett (Labor, Kingsford Smith, New South Wales) and Malcolm Turnbull (Liberal, Wentworth, New South Wales) easily won their contests. Prominent clergyman Fred Nile failed to win a Senate seat in New South Wales. The first Muslim candidate to be endorsed by a major party in Australia, Ed Husic, failed to win the seat of Greenway, New South Wales, for Labor. The former One Nation leader, Pauline Hanson, failed in her bid to win a Senate seat in Queensland as an independent.

Minor parties had mixed results. The Australian Democrats polled their lowest vote since their creation in 1977, and did not retain any of the three Senate seats they were defending. The Australian Greens won their first Senate seat in Western Australia and retained the Seat they were defending in Tasmania. They did not achieve a widely expected Senate Seat in Victoria, due to fellow progressive parties, the Australian Labor Party and The Australian Democrats, as well as some micro parties, joining with the conservative parties in a preference deal with far-right evangelist Christian party Family First, which despite a popular vote of just 1.7% received so many preferences from the unsuccessful Candidates of other parties that it eventually overtook the Greens David Risstrom's 7.4% vote and claimed that Senate Seat. As predicted, the Greens did not gain Senate seats in Queensland or South Australia, partly because of similar preference deals by fellow progressive parties, but also because of a traditionally lower vote in these States. Predictably, the Greens lost their first and (at the time) only Lower House seat of Cunningham, which they had gained by way of an electoral anomaly at the 2002 by-election in that Seat, which when The Liberal Party did not provide a Candidate, caused atypical voting patterns, overwhelmingly amongst voters who would normally have voted for The Liberals and did not want to vote for their traditional nemeses, The Labor Party.

The Australian Progressive Alliance leader, Senator Meg Lees, and the One Nation parliamentary leader, Senator Len Harris, lost their seats. One Nation's vote in the House of Representatives collapsed. The Christian Democratic Party, the Citizens Electoral Council, the Democratic Labor Party, the Progressive Labour Party and the Socialist Alliance all failed to make any impact. The Family First Party polled 2% of the vote nationally, and their candidate Steve Fielding won a Senate seat in Victoria.