Craven in New Zealand in 1956 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Birth name | Daniël Hartman Craven | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date of birth | 11 October 1910 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Place of birth | Lindley, Free State, South Africa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Date of death | 4 January 1993 (aged 82) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Place of death | Stellenbosch, South Africa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.78 m (5 ft 10 in) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Weight | 80 kg (176 lb) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| School | Lindley High School | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| University | Stellenbosch University | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation(s) | President of South African Rugby ('56–'93) Director of Sport ('76–'84) Professor of Physical Education ('49–'75) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rugby union career | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

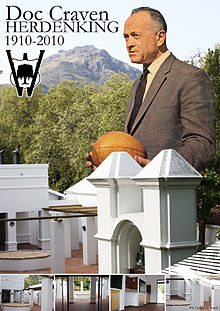

Daniël Hartman Craven (11 October 1910 – 4 January 1993) was a South African rugby union player (1931–1938), national coach, national and international rugby administrator, academic, and author. Popularly known as Danie, Doc, or Mr Rugby, Craven's appointment from 1949 to 1956 as coach of the Springboks signalled "one of the most successful spells in South African rugby history" during which the national team won 74% of their matches.[5] While as a player Craven is mostly remembered as one of rugby's greatest dive-passing scrumhalves ever,[2] he had also on occasion been selected to play for the Springboks as a centre, fly-half, No.8, and full-back. As the longest-serving President of the South African Rugby Board (1956–93) and chairman of the International Rugby Board (1962, 1973, 1979), Craven became one of the best-known and most controversial rugby administrators. In 1969, Craven sparked outrage among anti-apartheid activists when he allegedly said, "There will be a black springbok over my dead body".[6][2][7] Craven denied saying this and in his later career promoted coloured training facilities.

Craven earned doctorates in ethnology (1935), psychology (1973) and physical education (1978). He not only created the physical training division of the South African Defence Force (1941) but became the first professor of physical education at Stellenbosch University (1949).[2][8]

Danie Craven was born on 11 October 1911 to James Roos Craven (b. 28 June 1882) and Maria Susanna Hartman (d. 1958) on Steeton Farm near Lindley, a small town on the Vals River in eastern Free State province of South Africa.[9][10] Craven was the third of seven children. The family farm was named for Steeton in West Yorkshire, home to Craven's paternal grandfather, John Craven (1837–90), who came to South Africa as a diamond prospector.[8] Craven later also named his home in Stellenbosch Steeton.[2] His father, aged 18, fought against the British during the Anglo-Boer War and was interned in a British concentration camp, a fate that reportedly also befell his mother.[11][12]

As a young boy Craven played barefoot soccer, and received his first lessons at a farm school. At the age of 13 he was sent to Lindley High School, and started playing rugby with a stone in the dusty town streets.[13] At school he shone at cricket and rugby.[14] In the following year Craven was selected to play for the town's adult team, but his principal, Tivoli van Huyssteen, prevented him from playing until he turned 15.[8][13] Among his Lindley teammates was Lappies Hattingh, who would play with Craven 8 years later in the Springbok team against the Wallabies.[1]

In 1929 Craven enrolled at Stellenbosch University in the Western Cape. He initially registered as a theology student,[8] but later switched to Social Sciences and Social Anthropology.[13] The switch was prompted by medical advice after his vocal chords were damaged by a kick to the throat while he tried to stop charging forwards during the 1932 test against Scotland.[1]

Craven lodged in Wilgenhof Men's Residence, following in the footsteps of his maternal grandfather, George Nathaniel Hayward (1886–1977). In 1903 Hayward had been one of Wilgenhof's first residents.[15] An all-round athlete, Craven represented his university in rugby, swimming (captain), water polo and baseball. He also participated in track and field, and played cricket, tennis, and soccer.[2]

Craven obtained his BA (1932) as well as a MA (1933) and PhD (1935) in ethnology at Stellenbosch. His PhD dissertation was titled Ethnological Classification of the South African Bantu. His third doctorate was for his thesis on Evolution of Modern Games.[16] He was appointed as Stellenbosch's first professor of physical education in 1949, and served in that capacity until 1975.[2]

After completing his education at Stellenbosch, Craven started teaching at St. Andrew's College in Grahamstown, Eastern Cape, in 1936.[1] He coached the school's rugby side, and while there he was selected for the 1937 Springbok tour.[2][17]

Craven joined the Union Defence Force in 1938 as director of physical education and was sent to Europe to study physical education in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, France, and Britain. The imminent outbreak of war forced the Cravens to return to South Africa. Craven was appointed head of physical education at the South African military academy with the rank of major. When his section was established as a separate Physical Training Brigade in 1947, Craven was promoted to lieutenant-colonel and director of the brigade.[1][8] His military career was momentarily interrupted in 1947 as he was appointed lecturer in the Union Education Department at Stellenbosch University before returning to the brigade.[2]

Due to his fame as a Springbok, Craven's image was used in Afrikaans language newspapers during the Second World War to encourage men to enlist. The advertisement showed Craven in uniform, looking into the distance and announcing, "I am playing in the biggest Springbok team ever; join me and score the most important try of your life."[18]

At university Craven found a mentor in Stellenbosch coach and national selector A.F. ("Oubaas Mark") Markötter, in charge of the university team from 1903 to 1957.[1][19] Markötter noticed Craven from the time he starting playing as a 19-year-old in 1929, and promoted him to the first team the following year.[14]

Craven was selected as a Springbok in 1931 before he had made his provincial debut for Western Province in 1932.[1][8] In a match against Free State in Bloemfontein that year he scored a hat-trick of tries in a performance regarded as one of his best.[1]

In 1936 he worked in Grahamstown, and so started playing for Eastern Province, alongside Flappie Lochner. At Craven's suggestion, Markötter ensured that Lochner went on the 1937 tour to New Zealand.[1]

Craven played his first test match on 5 December 1931 as scrum half at the age of 21 against Wales at St Helens, Swansea. His flyhalf was the captain, Bennie Osler. One of the other debutants that day was flanker André McDonald, who would later develop into the first specialist No. 8. Craven and McDonald became fast friends. His performance on a water-logged field led Die Burger to exult "Boy plays like a giant".[1][20]

In his third test, against Scotland at Murrayfield on 16 January 1932, Craven scored the winning try. The opportunity came because Craven implemented advice that he had received at Stellenbosch from coach Markötter. Markötter had said that on a muddy field a scrumhalf should either play with his forwards or kick, Craven recalled later. His advice enabled Craven to choose between captain Osler, who wanted the ball to be passed to him, and leader of the forwards Boy Louw, who demanded that the ball stay with the forwards.[21] During the match he was knocked unconscious, sustained damage to his vocal chords, and lost a tooth.[1]

Craven's last test match was on 10 September 1938 as captain (also as scrum half) at the age of 27 against the British Lions at Newlands, Cape Town. During the 1930s he was one of the world's leading scrumhalves, but the start of the Second World War in 1939 ended his career prematurely.

| Opponents | Results (RSA 1st) | Position | Points | Dates | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wales | 8–3 | Scrum-half | – | 5 December 1931 | St Helen's, Swansea |

| Ireland | 8–3 | Scrum-half | – | 19 December 1931 | Lansdowne Road, Dublin |

| Scotland | 6–3 | Scrum-half | 3 (try) | 16 January 1932 | Murrayfield, Edinburgh |

| Australia | 17–3 | Scrum-half | 3 (try) | 8 July 1933 | Newlands, Cape Town |

| Australia | 6–21 | Scrum-half | - | 22 July 1933 | Kingsmead, Durban |

| Australia | 12–3 | Scrum-half | - | 12 August 1933 | Ellis Park, Johannesburg |

| Australia | 11–0 | Centre | - | 26 August 1933 | Crusaders Grounds, Port Elizabeth |

| Australia | 4–15 | Scrum-half | - | 2 September 1933 | Springbok Park, Bloemfontein |

| Australia | 9–5 | Fly-half | - | 26 June 1937 | Sydney Cricket Ground |

| Australia | 26–17 | No. 8 | - | 17 July 1937 | Sydney Cricket Ground |

| New Zealand | 7–13 | Fly-half (C) | - | 14 August 1937 | Athletic Park, Wellington |

| New Zealand | 13–6 | Scrum-half | - | 4 September 1937 | Lancaster Park, Christchurch |

| New Zealand | 17–6 | Scrum-half | - | 25 September 1937 | Eden Park, Auckland |

| Great Britain | 26–12 | Scrum-half (C) | - | 6 August 1938 | Ellis Park, Johannesburg |

| Great Britain | 19–3 | Scrum-half (C) | - | 3 September 1938 | Crusaders Grounds, Port Elizabeth |

| Great Britain | 16–21 | Scrum-half (C) | - | 10 September 1938 | Newlands, Cape Town |

After his rugby-playing career ended, he was a national selector from 1938 until he was appointed coach in 1949. He started his coaching career with a bang, winning 10 matches in a row, including a 4–0 whitewash of New Zealand in their 1949 tour to South Africa. Under his guidance the Springboks were undefeated from 1949 to 1952, and won 17 of 23 tests (74% success rate) – an achievement that makes Craven one of South Africa's greatest coaches. He also coached Stellenbosch University from 1949 until 1956.[2]

Craven became the president of the South African Rugby Board (SARB) in 1956. He was also a member of the International Rugby Board from 1957 and served as its chairman on several occasions.[2]

The last part of Craven's chairmanship of the SARB occurred during the country's most tumultuous years. Rugby had become the national sport of white South Africans and a symbol of Afrikaner power. In the 1970s and 1980s, the outlawed African National Congress allied with overseas anti-apartheid movements to successfully isolate South Africa from sporting and cultural contact with the rest of the world. Of all the sanctions aimed at South Africa, none irked the Afrikaner population more than the ban on rugby internationals.[22]

Craven managed to maintain links with other rugby playing nations during the years of South Africa's sporting isolation through his position with the IRB. He feared that isolation would negatively affect the standard of Springbok rugby. Consequently, he was not above "some murky business", such as the New Zealand Cavaliers tour in 1986, which Craven denied would happen. By the time South Africa returned to international competition in 1992, there had been no outgoing tours since 1981, and no incoming tours since 1984.[8]

In 1988 Craven met leaders of the African National Congress (ANC) in Harare, Zimbabwe in a bold bid to return to global competition.[8][23] An unprecedented deal emerged to form a single rugby association that would field integrated teams for participation in foreign tournaments. Many right-wing white South Africans attacked Craven as a traitor for meeting with the ANC, and then-president P.W. Botha denounced the move.[22] Although the deal did not lead to the immediate end of the sporting isolation, it paved the way for the formation of the unified body, the South African Rugby Football Union (SARFU) in 1992. Craven was SARFU's first chairman until he died in 1993, having served for an unbroken 37 years at the head of South African rugby.[8]

Craven married twice. He wed Beyera Johanna (née Hayward, d. 2007[24]) on 2 July 1938.[1] She was from the Eastern Cape, a teacher, and daughter of the member of parliament for Steytlerville, George Hayward.[1][2] Danie and Beyera had four children: Joan, George Hayward, Daniel, and James Roos Craven.[25] One of his grandsons is the professional Namibian road cyclist Dan Craven, winner of the 2008 African Road Race Championships in Casablanca, Morocco. Danie and Beyera divorced in 1972.[26]

On 30 May 1975 Craven married Martha Jacoba (Merlė) Vermeulen, the widow of Cape Town detective Dirk Vermeulen. Merlė worked in the fashion industry as a buyer for a chain of stores, and so had to attend fashion parades. After one such a parade in Pretoria, she twisted her ankle badly at her hotel. A bystander introduced her to Craven as "a doctor" who "knew a lot about ankle injuries". After Craven treated her foot, he telephoned and arranged to meet her again, and their relationship developed.[13][27]

Craven had a dog named Bliksem which accompanied him everywhere, even to rugby practices. A journalist recalled how "when Doc and Bliksem[28] were on the touchline at training, no one within sight would dare shirk".[29]

There were "many contradictions and convolutions in Craven's life", wrote Paul Dobson, which made him both admired and despised:

His home language was Afrikaans, but he would claim not to be an Afrikaner ... a sportsman and yet he set higher store by academic achievement ... accused of trying to hang on to an exclusively white preserve, and yet he devoted himself to breaking down racial barriers[30]

Danie Craven was accepted into the International Rugby Hall of Fame in 1997, the first of 9 South Africans to date.[31] In 2007 he became the third inductee into the IRB Hall of Fame, only preceded by Rugby School and William Webb Ellis, the alleged instigator of the game that would develop into rugby union.[2]

The South African Craven Week schools rugby competition is named after him, as well as the Danie Craven Stadium and Danie Craven Rugby Museum in Stellenbosch. To commemorate him, Stellenbosch University commissioned sculptor Pierre Volschenk to execute a bronze sculpture of Craven and his faithful dog. The statue stands within the grounds of the Coertzenburg sports complex in Stellenbosch.[32]

In 1981 Craven received the State President's Award for Exceptional Service, as well as the honorary citizenship of the city of Stellenbosch.[1] He was made an honorary life president of the French Rugby Federation in 1992.[7]

Craven is often remembered for his quirky and controversial statements. For example, he said "When Maties and Western Province rugby are strong, then Springbok rugby is strong."

Initially he was unsure that all South Africans could play together, arguing in 1968 that the different race groups were "separate nations ... [who] won't ever play in the same side. But maybe ... one day, we would have such a team".[33] Craven denied that he had ever said that people of colour would be Springboks "over my dead body".[8] His supporters could point to his liking for coloured rugby enthusiasts, and the efforts that he made over the last few years of his life to run multiracial rugby workshops in rural South Africa as signs that he had changed his views.[8]

Apart from his academic dissertations which were referred to above, Craven wrote numerous books as solo and co-author on rugby, including his autobiography (1949), rugby terms for translators (1972), and how to organize a tennis club (1951). According to The Independent of London "his coaching manual Rugby Handbook (1970) is a standard".[8]

Partial list.