| Day | Event | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 33 | posterior commissure appears | Ashwell et al. (1996)[2] |

| 33 | medial forebrain bundle appears | Ashwell et al. (1996)[2] |

| 44 | mammillothalamic tract appears | Ashwell et al. (1996)[2] |

| 44 | stria medullaris thalami appears | Ashwell et al. (1996)[2] |

| 51 | axons in optic stalk | Dunlop et al. (1997)[3] |

| 56 | external capsule appears | Ashwell et al. (1996)[2] |

| 56 | stria terminalis appears | Ashwell et al. (1996)[2] |

| 60 | optic axons invade visual centers | Dunlop et al. (1997)[3] |

| 63 | internal capsule appears | Ashwell et al. (1996)[2] |

| 63 | fornix appears | Ashwell et al. (1996)[2] |

| 70 | anterior commissure appears | Ashwell et al. (1996)[2] |

| 77 | hippocampal commissure appears | Ashwell et al. (1996)[2] |

| 87.5 | corpus callosum appears | Ashwell et al. (1996)[2] |

| 157.5 | eye opening | Clancy et al. (2007)[4] |

| 175 | ipsi/contra segregation in LGN and SC | Robinson & Dreher (1990)[5] |

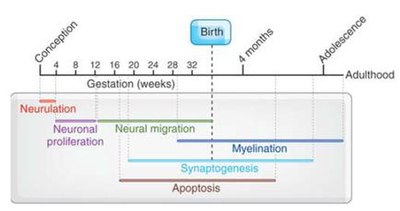

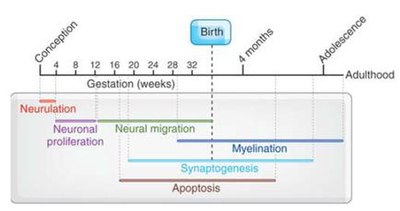

Studies report that three primary structures are formed in the sixth gestational week. These are the forebrain, the midbrain, and the hindbrain, also known as the prosencephalon, mesencephalon, and the rhombencephalon respectively. Five secondary structures originate from these in the seventh gestational week. These are the telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon, metencephalon, and myelencephalon; the lateral ventricles, third ventricles, cerebral aqueduct, and upper and lower parts of the fourth ventricle in adulthood originated from these structures.[6] The appearance of cortical folds first takes place during 24 and 32 weeks of gestation.[7]

Cortical white matter increases from childhood (~9 years) to adolescence (~14 years), most notably in the frontal and parietal cortices.[8] Cortical grey matter development peaks at ~12 years of age in the frontal and parietal cortices, and 14–16 years in the temporal lobes (with the superior temporal cortex being last to mature), peaking at about roughly the same age in both sexes according to reliable data. In terms of grey matter loss, the sensory and motor regions mature first, followed by other cortical regions.[8] Human brain maturation continues to around 20[9] to 25[10] and even up to 30[11] years of age and beyond. Although it is worth noting that there is no actual evidence suggesting that impulse control only finishes developing in humans in the twenties. It is a common misconception that the brain only fully develops by 25, as the number comes from two particular studies, one on psychosocial maturity, where greater than 50% of people being tested only reached a plateau in impulse control by the age of 25. However, some people were recorded to have reached adult-levels by mid-teens, and some had not reached it even after 30. It is worth noting that the majority of countries showed that people's impulse control linearly improved with age, suggested that most cutoffs are somewhat arbitrary. It is also believed to have originated from a study by Jay Giedd based on MRI data, scanning the brains of people aged up to 21 or 25 years and no participants that were older. Years of research and testing seem to indicate that the brain is functioning in full adult capacity by the time youths reach high school, or roughly the age range of 14-16. Though it is a controversial psychometric, adult IQ also begins to be tested around this age range, with the Raven's Progressive Matrices test beginning at age 14 and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale test beginning at age 16, though scores between 14 and 16 on the Weschler test have differences so small that they are considered unreliable. This may bring into question the effectiveness of brain development studies in treating and successfully rehabilitating criminal youth.[12]