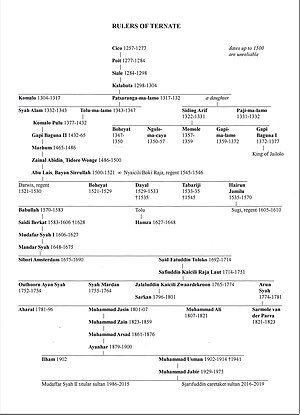

Rulers of Ternate

Pre-Sultanate rulers

|

Main article: Pre-Islamic rulers of Ternate |

- Cico (king [kolano] 1257-1277)

- Poit (1277-1284) [son]

- Siale (1284-1298) [son]

- Kalabata (1298-1304) [son]

- Komalo (1304-1317) [son]

- Patsaranga-ma-lamo (1317-1322) [brother]

- Siding Arif (1322-1331) [nephew]

- Paji-ma-lamo (1331-1332) [brother]

- Syah Alam (1332-1343) [son of Patsaranga-ma-lamo]

- Tolu-ma-lamo (1343-1347) [brother]

- Boheyat I (1347-1350) [son of Siding Arif]

- Ngolo-ma-Caya (1350-1357) [brother]

- Momole (1357-1359) [brother]

- Gapi-ma-lamo (1359-1372) [brother]

- Gapi Baguna I (1372-1377) [brother]

- Komalo Pulu (1377-1432) [son of Tolu-ma-lamo]

- Gapi Baguna II (1432-1465) [son]

- Marhum (1465-1486) [son]

Sultan

| Sultan of Ternate | |

|---|---|

Imperial | |

| |

| Details | |

| Style | His Highness[5] |

| First monarch | Zainal Abidin |

| Last monarch | Muhammad Usman Syah (Last Sultan to rule Ternate) Muhammad Jabir Syah (Honorary Sultan) |

| Formation | c. 1486 |

| Abolition |

|

| Residence | Known residences:

|

| Appointer |

|

| Pretender(s) | Sjarifuddin Sjah (titular Sultan of Ternate 2016-2019)[4] |

The first known Kolano (ruler) of Ternate to convert to Islam was Marhum. According to François Valentijn's account, Marhum was the son and successor of the seventeenth King Gapi Baguna II (r. 1432-1465), a pre-Islamic ruler of Ternate. His island kingdom was one of the four realms that traditionally existed in North Maluku, the others being Tidore, Bacan, and Jailolo. Reports were told by Javanese traders who came to the island, that native Ternateans were able to read out words from the letters of the Qur'an, it proves that the first tenets of Islam had entered North Molluccan society.[6]

The first ruler of Ternate to adopt the title of Sultan was Zainal Abidin of Ternate, His life is only described in sources dating from the 16th century or later.[7] According to the versions of François Valentijn's account, Zainal Abidin was the son of Marhum, meanwhile according to Malay Annals like the Hikayat Tanah Hitu by Rijali (written before 1657 and later adjusted in c. 1700) described that Zainal Abidin was the first Ternate ruler to convert to Islam.[8] Many Muslim Javanese traders frequented Ternate at the time and incited the king to learn more about the new creed, to establish an Islamic governance for his kingdom. In c. 1495, he traveled with his companion Hussein to study Islam in Giri (Gresik) on Java's north coast, where Sunan Giri kept a well-known madrasa.[9] While there, he won renown as Sultan Bualawa, or Sultan of Cloves.[10] According to the Hikayat Tanah Hitu, Zainal Abidin stopped in Bima in Sumbawa on his way back to Maluku. He and his crew got into trouble with the local king and a fight took place where a Bimanese wounded Zainal Abidin with his spear. The bodyguards of the ruler brought him back to the ship, though he died on board. The account of François Valentijn, on the contrary, insists that he survived the battle and made it back to Ternate.[11] On his return, he replaced the royal title Kolano with Sultan, and it may have been now that he adopted the Islamic name Zainal Abidin.[12] He brought back a mubaligh from Java named Tuhubahahul to propagate the Islamic faith and created a Bobato (headman) to assist in all matters relating to the rule of Islamic law across the Sultanate.[13]

The second ruler of ternate to claim the title of Sultan was Bayan Sirrullah, he ruled somewhere around 1500 to 1521 and saw the arrival of Portuguese to the Island of Maluku. Bayan Sirrullah also known as Abu Lais (in Portuguese sources, Boleife), was the eldest son of the first sultan of Ternate, Zainal Abidin.[14] Islam had been accepted by the local elites of North Maluku in the second half of the 15th century, as a consequence of the importance of Muslim traders in the archipelago.[15]

Under the reign of Baabullah of Ternate, Ternate saw its golden age after Baabullah's victory in defeating the Portuguese. He was commonly known as the Ruler of 72 (Inhabited) Islands in eastern Indonesia, including most of the Maluku Islands, Sangihe and parts of Sulawesi, with influences as far as Solor, East Sumbawa, Mindanao, and the Papuan Islands.[16] His reign inaugurated a period of free trade in the spices and forest products that gave Maluku a significant role in Asian commerce.[17]

The last Sultan of Ternate was Muhammad Usman Syah. Muhammad Usman succeeded to the throne in February 1902 after the death of his father in 1900, and his brother's short period reign. He was arrested and dethroned by the Dutch colonial authorities on 23 September 1915[18][19][20] because of his opposition to the increasing colonial interference in his kingdom and the subsequent minor uprising in Jailolo in September 1914, whereby the controleur G.K.B. Agerbeek and Lieutenant C.F. Ouwerling were murdered. The Dutch colonial government later enthroned an honorary sultan of Ternate, Muhammad Jabir in 1929,[21][22] the sultanate was de facto abolished under the government of Indonesia around 1949 to 1950.[23]

List of Sultans:[24]

- Zainal Abidin (1486-1500) [son; first sultan]

- Bayan Sirrullah (1500-1521) [son]

- Boheyat II (1522-1529) [son]

- Dayal (1529-1533; died 1536) [brother]

- Tabariji (1533-1535) [brother]

- Hairun Jamilu (1535-1570) [brother]

- Babullah (1570-1583) [son]

- Saidi Berkat (1583-1606; died 1628) [son]

- Mudafar Syah I (1607-1627) [son]

- Hamza (1627-1648) [grandson of Hairun Jamilu]

- Mandar Syah (1648-1675) [son of Muzaffar Syah I]

- Sibori Amsterdam (1675-1689) [son]

- Dutch protectorate 1683-1915

- Said Fatuddin Toloko (1689-1714) [brother]

- Kaicili Raja Laut (1714-1751) [son]

- Outhoorn Ayan Syah (1752-1755) [son]

- Amir Iskandar Muda Syah, Syah Mardan (1755-1764) [brother]

- Jalaluddin, Kaicili Zwaardekroon (1764-1774) [brother]

- Arun Syah (1774-1781) [brother]

- Aharal (1781-1796) [son]

- Sarkan (1796-1801) [son of Jalaluddin Kaicili Zwaardekroon]

- Muhammad Jasin (1801-1807) [son of Arun Syah]

- Muhammad Ali (1807-1821; died 1824) [brother]

- Sarmole van der Parra (1821-1823) [brother]

- Muhammad Zain 1823-1859) [son of Muhammad Jasin]

- Muhammad Arsad (1861-1876) [son]

- Ayanhar (1879-1900) [son]

- Ilham (1900-1902) [son]

- Muhammad Usman (1902-1915; died 1941) [brother]

- Interregnum 1915-1929

- Iskandar Muhammad Jabir Syah (1929-1975) [son]

- Incorporation into Indonesian unitary state 1950

- Mudaffar Sjah II (titular sultan 1986-2015) [son]

- Sjarifuddin Sjah (titular sultan 2016-2019) [brother][25]