| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Magnesium hydride

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.824 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| MgH2 | |

| Molar mass | 26.3209 g/mol |

| Appearance | white crystals |

| Density | 1.45 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 327 °C (621 °F; 600 K) decomposes |

| decomposes | |

| Solubility | insoluble in ether |

| Structure | |

| tetragonal | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Heat capacity (C)

|

35.4 J/mol K |

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

31.1 J/mol K |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

-75.2 kJ/mol |

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵)

|

-35.9 kJ/mol |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

pyrophoric[1] |

| Related compounds | |

Other cations

|

Beryllium hydride Calcium hydride Strontium hydride Barium hydride |

| Magnesium monohydride Mg4H6 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Magnesium hydride is the chemical compound with the molecular formula MgH2. It contains 7.66% by weight of hydrogen and has been studied as a potential hydrogen storage medium.[2]

Preparation

[edit]In 1951 preparation from the elements was first reported involving direct hydrogenation of Mg metal at high pressure and temperature (200 atmospheres, 500 °C) with MgI2 catalyst:[3]

- Mg + H2 → MgH2

Lower temperature production from Mg and H2 using nanocrystalline Mg produced in ball mills has been investigated.[4] Other preparations include:

- the hydrogenation of magnesium anthracene under mild conditions:[5]

- Mg(anthracene) + H2 → MgH2

- the reaction of diethylmagnesium with lithium aluminium hydride[6]

- product of complexed MgH2 e.g. MgH2.THF by the reaction of phenylsilane and dibutyl magnesium in ether or hydrocarbon solvents in the presence of THF or TMEDA as ligand.[1]

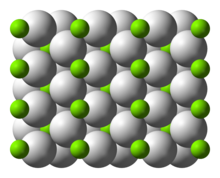

Structure and bonding

[edit]The room temperature form α-MgH2 has a rutile structure.[7] There are at least four high pressure forms: γ-MgH2 with α-PbO2 structure,[8] cubic β-MgH2 with Pa-3 space group,[9] orthorhombic HP1 with Pbc21 space group and orthorhombic HP2 with Pnma space group.[10] Additionally a non stoichiometric MgH(2-δ) has been characterised, but this appears to exist only for very small particles[11]

(bulk MgH2 is essentially stoichiometric, as it can only accommodate very low concentrations of H vacancies[12]).

The bonding in the rutile form is sometimes described as being partially covalent in nature rather than purely ionic;[13] charge density determination by synchrotron x-ray diffraction indicates that the magnesium atom is fully ionised and spherical in shape and the hydride ion is elongated.[14] Molecular forms of magnesium hydride, MgH, MgH2, Mg2H, Mg2H2, Mg2H3, and Mg2H4 molecules identified by their vibrational spectra have been found in matrix isolated samples at below 10 K, formed following laser ablation of magnesium in the presence of hydrogen.[15] The Mg2H4 molecule has a bridged structure analogous to dimeric aluminium hydride, Al2H6.[15]

Reactions

[edit]MgH2 readily reacts with water to form hydrogen gas:

- MgH2 + 2 H2O → 2 H2 + Mg(OH)2

At 287 °C it decomposes to produce H2 at 1 bar pressure.[16] The high temperature required is seen as a limitation in the use of MgH2 as a reversible hydrogen storage medium:[17]

- MgH2 → Mg + H2

References

[edit]- ^ a b Michalczyk, Michael J (1992). "Synthesis of magnesium hydride by the reaction of phenylsilane and dibutylmagnesium". Organometallics. 11 (6): 2307–2309. doi:10.1021/om00042a055.

- ^ Bogdanovic, Borislav (1985). "Catalytic Synthesis of Organolithium and Organomagnesium Compounds and of Lithium and Magnesium Hydrides - Applications in Organic Synthesis and Hydrogen Storage". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 24 (4): 262–273. doi:10.1002/anie.198502621.

- ^ Egon Wiberg; Heinz Goeltzer; Richard Bauer (1951). "Synthese von Magnesiumhydrid aus den Elementen" [Synthesis of Magnesium Hydride from the Elements] (PDF). Zeitschrift für Naturforschung B (in German). 6b: 394.

- ^ Zaluska, A; Zaluski, L; Ström–Olsen, J.O (1999). "Nanocrystalline magnesium for hydrogen storage". Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 288 (1–2): 217–225. doi:10.1016/S0925-8388(99)00073-0.

- ^ Bogdanović, Borislav; Liao, Shih-Tsien; Schwickardi, Manfred; Sikorsky, Peter; Spliethoff, Bernd (1980). "Catalytic Synthesis of Magnesium Hydride under Mild Conditions". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 19 (10): 818. doi:10.1002/anie.198008181.

- ^ Barbaras, Glenn D; Dillard, Clyde; Finholt, A. E; Wartik, Thomas; Wilzbach, K. E; Schlesinger, H. I (1951). "The Preparation of the Hydrides of Zinc, Cadmium, Beryllium, Magnesium and Lithium by the Use of Lithium Aluminum Hydride1". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 73 (10): 4585. doi:10.1021/ja01154a025.

- ^ Zachariasen, W. H; Holley, C. E; Stamper, J. F (1963). "Neutron diffraction study of magnesium deuteride". Acta Crystallographica. 16 (5): 352. doi:10.1107/S0365110X63000967.

- ^ Bortz, M; Bertheville, B; Böttger, G; Yvon, K (1999). "Structure of the high pressure phase γ-MgH2 by neutron powder diffraction". Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 287 (1–2): L4–L6. doi:10.1016/S0925-8388(99)00028-6.

- ^ Vajeeston, P; Ravindran, P; Hauback, B. C; Fjellvåg, H; Kjekshus, A; Furuseth, S; Hanfland, M (2006). "Structural stability and pressure-induced phase transitions inMgH2". Physical Review B. 73 (22): 224102. Bibcode:2006PhRvB..73v4102V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.73.224102.

- ^ Moriwaki, Toru; Akahama, Yuichi; Kawamura, Haruki; Nakano, Satoshi; Takemura, Kenichi (2006). "Structural Phase Transition of Rutile-Type MgH2at High Pressures". Journal of the Physical Society of Japan. 75 (7): 074603. Bibcode:2006JPSJ...75g4603M. doi:10.1143/JPSJ.75.074603.

- ^ Schimmel, H. Gijs; Huot, Jacques; Chapon, Laurent C; Tichelaar, Frans D; Mulder, Fokko M (2005). "Hydrogen Cycling of Niobium and Vanadium Catalyzed Nanostructured Magnesium". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (41): 14348–54. doi:10.1021/ja051508a. PMID 16218629.

- ^ Grau-Crespo, R.; K. C. Smith; T. S. Fisher; N. H. de Leeuw; U. V. Waghmare (2009). "Thermodynamics of hydrogen vacancies in MgH2 from first-principles calculations and grand-canonical statistical mechanics". Physical Review B. 80 (17): 174117. arXiv:0910.4331. Bibcode:2009PhRvB..80q4117G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.80.174117. S2CID 32342746.

- ^ Cotton, F. Albert; Wilkinson, Geoffrey; Murillo, Carlos A.; Bochmann, Manfred (1999), Advanced Inorganic Chemistry (6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 0-471-19957-5

- ^ Noritake, T; Towata, S; Aoki, M; Seno, Y; Hirose, Y; Nishibori, E; Takata, M; Sakata, M (2003). "Charge density measurement in MgH2 by synchrotron X-ray diffraction". Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 356–357: 84–86. doi:10.1016/S0925-8388(03)00104-X.

- ^ a b Wang, Xuefeng; Andrews, Lester (2004). "Infrared Spectra of Magnesium Hydride Molecules, Complexes, and Solid Magnesium Dihydride". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 108 (52): 11511. Bibcode:2004JPCA..10811511W. doi:10.1021/jp046410h.

- ^ McAuliffe, T. R. (1980). Hydrogen and Energy (illustrated ed.). Springer. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-349-02635-7. Extract of page 65

- ^ Schlapbach, Louis; Züttel, Andreas (2001). "Hydrogen-storage materials for mobile applications" (PDF). Nature. 414 (6861): 353–8. Bibcode:2001Natur.414..353S. doi:10.1038/35104634. PMID 11713542. S2CID 3025203.