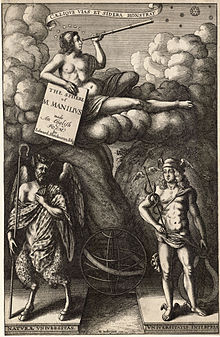

Marcus Manilius (fl. 1st century AD) originally hailing from Syria, was a Roman poet, astrologer, and author of a poem in five books called Astronomica.[1][2]

|

Main article: Astronomica (Manilius) |

The author of Astronomica is neither quoted nor mentioned by any ancient writer. Even his name is uncertain, but it was probably Marcus Manilius; in the earlier books the author is anonymous, the later give Manilius, Manlius, Mallius. The poem itself implies that the writer lived under Augustus or Tiberius, and that he was a citizen of and resident in Rome, suggesting that Manilius wrote the work during the 20s CE. According to the early 18th-century classicist Richard Bentley, he was an Asiatic Greek; according to the 19th-century classicist Fridericus Jacob, an African. His work is one of great learning; he had studied his subject in the best writers, and generally represents the most advanced views of the ancients on astronomy (or rather astrology).[3]

Manilius frequently imitates Lucretius. Although his diction presents some peculiarities, the style is metrically correct, and he could write neat and witty hexameters.[3]

The astrological systems of houses, linking human affairs with the circuit of the zodiac, have evolved over the centuries, but they make their first appearance in Astronomica. The earliest datable surviving horoscope that uses houses in its interpretation is slightly earlier, c. 20 BCE. Claudius Ptolemy (c. 130–170 CE) almost completely ignored houses (templa as Manilius calls them) in his astrological text, Tetrabiblos.[3]

The work is also known for being the subject of the most salient of A. E. Housman's scholarly endeavours; his annotated edition he considered his magnum opus, and when the fifth and final volume was published in 1930, 27 years after the first, he remarked he would now "do nothing forever and ever." He nonetheless also thought that it was an obscure pursuit; to an American correspondent he wrote, "I do not send you a copy, as it would shock you very much; it is so dull that few professed scholars can read it, probably not one in the whole United States."[4] It remains a source of bafflement to many that Housman should have elected to abandon (as they thought) a poet like Propertius in favour of Manilius. For example, the critic Edmund Wilson pondered the countless hours Housman devoted to Manilius and concluded, "Certainly it is the spectacle of a mind of remarkable penetration and vigor, of uncommon sensibility and intensity, condemning itself to duties which prevent it from rising to its full height." This is, however, to misunderstand the technical task of editing a classical text.[5] In the same vein, Harry Eyres interpreted it as "what you could see as an act of self-punishment" that so many years were devoted to "a minor Roman versifier whose long didactic poem on astrology must rank as one of the most obscure in the entire annals of poetry".[6]

An impact crater on the Moon is named after him: Manilius is located in the Mare Vaporum.