The Roman tuba, or trumpet[1][2] was a military signal instrument used by the ancient Roman military and in religious rituals.[3][4][5] They would signal troop movements such as retreating,[6] attacking, or charging,[7][8] as well as when guards should mount, sleep,[9] or change posts.[7][10] Thirty-six or thirty-eight tubicines were assigned to each Roman legion.[11][12] The tuba would be blown twice each spring in military, governmental, or religious functions. This ceremony was known as the tubilustrium. It was also used in ancient Roman triumphs.[13][14][15] It was considered a symbol of war and battle.[16] The instrument was used by the Etruscans in their funerary rituals.[17] It continued to be used in ancient Roman funerary practices.[18]

Roman tuba were usually straight cylindrical instruments with a bell at the end.[2][5][19][20] They were typically made of metals such as silver,[21] bronze, or lead and measured around 4.33 ft or 1.31 meters.[6][22] Their players, known as the tubicines or tubatores were well-respected in Roman society.[23][24][25] The tuba was only capable of producing rhythmic sounds on one or two pitches.[26] Its noise was often described as terrible, raucous, or hoarse.[27] Ancient writers describe the tuba as invoking fear and terror in those who heard it.[28]

-

Roman tuba found in archaeological site of Roman Villa di San Vincenzino, Italy.

-

Reconstructed Roman tuba

-

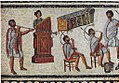

Musicians playing a Roman tuba, a water organ (hydraulis), and a pair of cornua, detail from the Zliten mosaic, 2nd century AD

-

Roman cornu (left) and tuba (right) in a relief from the Museo Ostiense, Ostia Antica, Italy.