Romanticism was an intellectual movement that arose in the late eighteenth century and continued through the nineteenth century. The movement had roots in the arts, literature, and science. Largely conceived as a reaction towards the extreme rationalism of the Enlightenment, it championed expressing emotions through aesthetic and emphasizing the transcendent allure of the natural world.

There has been significant work done by historians about how romanticism played a significant role in the development of modern theories of evolution. Most notable is the work done by Robert J. Richards, a professor at the University of Chicago. Richards, and others, have contributed significantly to the conversation about how Romanticism plays a significant role in evolution theory, especially regarding German Romanticism.

Charles Darwin became acquainted with Humboldt's exploration and science during while studying at Cambridge. Here, Darwin was taken under the direction of John Stevens Henslow (1796–1861), Professor of Botany, who strongly encouraged Darwin to travel and study nature. Henslow also encouraged Darwin to read Alexander von Humboldt's manuscripts on exploring nature, and it was, at least in part, Humboldt's work that inspired Darwin's romantic notion of travel and discovery.[1]

Prior to Darwin's departure on the H.M.S. Beagle, Henslow bestowed to Darwin the English translation of Humboldt's Relation historique du voyage aux regions equinoxiales du nouveau continent, which the translator (Helen Maria Williams) called Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America. Darwin read Humboldt's Personal Narrative thoroughly while on his own journey of scientific exploration on board the Beagle.[1]

Darwin and Humboldt spent their later years exchanging letters and manuscripts. After reading Darwin's writings from the Beagle, Humboldt wrote to Darwin: “You told me in your kind letter that, when you were young, the manner in which I studied and depicted nature in the torrid zones contributed toward exciting in you the ardor and desire to travel in distant lands. Considering the importance of your work, Sir, this may be the greatest success that my humble work could bring. Works are of value only if they give rise to better ones.[2]

The two men finally met in person in 1842. Humboldt died in 1859, sixth months before the first edition of On the Origin of Species was published. In letters to his close friend Joseph Dalton Hooker, Darwin reflected that his "whole course of life" was due to having read Humboldt's Personal Narrative and conclusively praised Humboldt as the "Greatest scientific traveller who ever lived."[1]

Historians have noted that Humboldt's vision of aesthetic appraisal and science was incredibly comprehensive and modern for his time: consequently, his work contributed to advancing observation in geography, geophysics, and natural history.[3] It has also been noted that Darwin's aesthetic approach to the natural world through his explorations and consequent observations was influenced by Humboldt's excursions and literature.[4]

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German Romantic poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, artist, and statesman whose works contributed significantly to natural history.

In 1790, Goethe wrote Versuch die Metamorphose der Pflanzen zu erklären (Metamorphosis of Plants) and Zur Morphologie, creating the scientific field of morphology, the branch of study in biology that deals with the structural forms of organisms. In his texts, Goethe used morphology to describe homology between parts of different organisms (for example, comparing the arm of a human to the fin of a whale). Goethe further suggested that adaptive modifications in an organism's parts were all relative to a Bauplan, an idealized, common archetype. Robert J. Richards suggests that Versuch die Metamorphose der Pflanzen zu erklären transformed biological sciences during this time period.[5] Historian Joan Steigerwald suggests that Goethe's morphology was inherently Romantic, as they were idealistic.[6] She also argues that Goethe's experiences with nature and aesthetics were the driving factors in his postulation of an "ideal" form (the Bauplan).[7]

Later evolutionists, including Carl Gegenbaur and Ernst Haeckel, used phenotypic variation first described by Goethe in his texts about morphology to advance the understanding of evolution. As a Romantic, Goethe also paved the way for equally influential Romantic-scientists, including Alexander von Humboldt and Friedrich Schelling. Professor Robert J. Richards of the University of Chicago argues that it was both the Romantic perspectives of Schelling and Goethe which paved the way for a nature-centric understanding of evolution.[8]

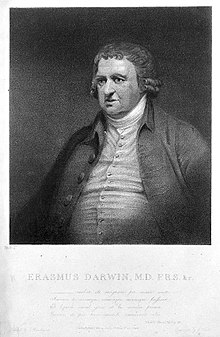

Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles Darwin, was born in Nottinghamshire on 12 December 1731 and died on 18 April 1802. He was a successful physician, botanist, and poet who contributed heavily to evolution theory through his works as a writer-naturalist. Though he is most often linked to the Age of Enlightenment and was an enthusiastic proponent of Materialism,[9] Erasmus Darwin's literary contributions popularized interest in the natural world, connecting him to the Romantic movement as well.

In the late 1770s, Erasmus Darwin diverged from his work as a well-known physician due to his interest in botany. In 1789, he composed "The Love of Plants" which was a collection of poetic verses concerning Carolus Linnaeus's taxonomic system, which he revered deeply. This book was so successful that Erasmus Darwin later included it in The Botanic Garden (1791), which was composed of two poems, "The Economy of Vegetation" and "The Loves of Plants." "The Economy of Vegetation" is focused on the evolution of mankind through technology and innovation and argues that industrialization was part of a single evolutionary process.

Conversely, "The Loves of Plants" was focused on uniting nature with man through the appreciation of botany. In it, Darwin encourages humans to study botany because plants are a part of the same natural world as man. He also argues that sexual reproduction gives rise to phenotypic change (which his grandson would later incorporate into his own theory of evolution put forth in On the Origin of Species).

In 1794, Erasmus Darwin also wrote Zoonomia, another book of verse, this time dealing with human physiology. In this volume, Erasmus Darwin presents himself as a Lamarckian evolutionist, advocating the "inheritance of acquired characteristics" theory.[10] He also suggests a theory of pangenesis in the third volume of Zoonomia, a hypothesis Charles Darwin later propelled.[11] The theories posited in Zoonomia are some of the first formal theories on evolution.[12]

Although Erasmus Darwin died seven years before Charles Darwin was born, the younger Darwin was not without his grandfather's teachings and works. Charles Darwin read Zoonomia when he was 18 years old and found it inspirational.[13]

However, as Charles Darwin got older, he began to resent Erasmus Darwin's work. In the "short historical preface" of his 1860 publication of Origin, Darwin denounced Lamarck's belief in "a law of progressive development," followed by a footnote: “It is curious how largely my grandfather, Dr. Erasmus Darwin, anticipated the views and erroneous grounds of Lamarck in his Zoonomia'”.[14] Erasmus Darwin, a proponent of Atheism, Materialism, and also provocative Romanticism, faced many obstacles in popularizing his views on evolution despite his success as a popular poet. Lamarck had faced similar dissent.[15] Darwin wished to avoid this association, which could impede on his own popularity among the public and the scientific community.[15] In 1879, Charles Darwin had become so polarized in his opinions about his grandfather that when wrote a biography on his grandfather titled The Life of Erasmus Darwin, it contained so much crudeness that Charles Darwin's daughter, Henriette Darwin, supposedly edited out 16% of the biography.[16]