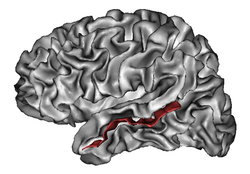

Part of the brain's temporal lobe

In the human brain, the superior temporal sulcus (STS) is the sulcus separating the superior temporal gyrus from the middle temporal gyrus in the temporal lobe of the brain. A sulcus (plural sulci) is a deep groove that curves into the largest part of the brain, the cerebrum, and a gyrus (plural gyri) is a ridge that curves outward of the cerebrum.[1]

The STS is located under the lateral fissure, which is the fissure that separates the temporal lobe, parietal lobe, and frontal lobe.[1] The STS has an asymmetric structure between the left and right hemisphere, with the STS being longer in the left hemisphere, but deeper in the right hemisphere.[2] This asymmetrical structural organization between hemispheres has only been found to occur in the STS of the human brain.[2]

The STS has been shown to produce strong responses when subjects perceive stimuli in research areas that include theory of mind, biological motion, faces, voices, and language.[3][4]

Language processing

Spoken language processing

The superior temporal sulcus also activates when hearing human voices.[5] It is thought to be a source of sensory encoding linked to motor output through the superior parietal-temporal areas of the brain inferred from the time course of activation. The conclusion of pertinence to vocal processing can be drawn from data showing that the regions of the STS are more active when people are listening to vocal sounds rather than non-vocal environmentally based sounds and corresponding control sounds, which can be scrambled or modulated voices.[6] These experimental results indicate the involvement of the STS in the areas of speech and language recognition.

The majority of studies find it is the middle to the posterior portion of the STS that is involved in phonological processing, with bilateral activation indicated though including a mild left hemisphere bias due to greater observed activation. However, the role of the anterior STS in the ventral pathway of speech comprehension and production has not been ruled out.[7] Evidence for the involvement of the middle portion of the STS in phonological processing comes from repetition-suppression studies, which use fMRI to pinpoint areas of the brain responsible for specialized stimulus involvement by habituating the brain to the stimulus and recording differences in stimulation response. The resulting pattern showed expected results in the middle portion of the STS.[8]

Studies using fMRI analysis to measure superior temporal sulcus activation have found that phonemes, words, sentences, and phonological cues all lead to increased activation throughout a posterior-anterior axis in the temporal lobe.[2] This pattern of activation, which most frequently occurs in the left hemisphere, has been termed the ventral stream of speech perception.[7] Many studies consistently indicate that the superior temporal sulcus activation is associated with the interpretation of phonological signals.[2] Although present research suggest that the left hemisphere of the superior temporal sulcus and its associated left ventral stream plays a role in phonological processing, the right hemisphere of the superior temporal sulcus has been connected to the perception of voice and the prosody of speech.[9]

According to the audiological pathway model supplied by Hickok and Poeppel, after the spectrotemporal analysis conducted by the auditory cortex, the STS is responsible for interpretation of vocal input through the phonological network. This implication is shown in the activation of the region in tasks of speech perception and processing, which necessarily involves access to and continuance of phonological information. By manipulating the interactions of phonological data, represented by the provision of words with high or low neighborhood density (words associated with many or few other words), the fluctuation of activity of the STS region can be seen. This changing activation links the STS with the phonological pathway.[7]

Sign language processing

Research shows that the Broca's area of the brain is activated during sign language production and processing.[10]

However, while the Broca's area plays a significant role, there are additional regions such as the posterior superior temporal gyrus and the left inferior parietal lobe that also play vital roles in the processing of sign language. Therefore, sign language engages with several regions of the brain, not simply the Brocas's area.[11]

Although Broca's area is found in the frontal lobe, it receives connection from the superior temporal gyrus, including the STS.[10] Native signers are people who learned and have been using sign language, such as American Sign Language (ASL), from birth, and/or use it as their first language.[12] They often learn sign language from their parents and continue its use throughout their lifetime.[12] Sign language activates language regions of the brain, including the STS.[13] There have been studies that show activation of the STS while deaf and hearing native signers perceive sign language, suggesting the STS is tied to the linguistic processing aspect of sign language.[14][15]

It is also important to highlight the importance of the superior temporal sulcus in its involvement throughout different parts of auditory and visual processing. The superior temporal sulcus is activated during the perception of sign language - this could potentially be related to visual-spatial and linguistic processing.[16][17]

Studies also show that there is greater activation of the middle STS in both deaf and hearing signers who acquired ASL earlier than those who acquired it later.[18]

Social processing

Studies reveal multiple social processing capabilities.[19] Research has documented activation in the STS as a result of five specific social inputs, and thus the STS is assumed to be implicated in social perception. It showed increased activation related to: theory of mind (false belief stories versus false physical stories), voices versus environmental sounds, stories versus nonsense speech, moving faces versus moving objects, and biological motion.[20][3] It is involved in the perception of where others are gazing (joint attention) and is important in determining where others' emotions are being directed.[21]

Theory of mind

Neuroimaging studies examining the theory of mind, otherwise known as the ability to attribute mental states to others, have identified the posterior superior temporal sulcus of the right hemisphere as being involved in its processing.[2] Activation of this region in the theory of mind has been found to be best predicted by independent ratings from other groups of participants, or more specifically, how much each item in the study made them consider the protagonist's point of view.[22] Reports noted in other studies suggest a number of inconsistencies with the localization of theory of mind processing, such as the middle and anterior portions of the superior temporal sulcus having increased activation in response to theory of mind tasks.[3] Thus, further research is needed to expand upon the precise functional role of the superior temporal sulcus in the perception of theory of mind.

Face perception

A recent study identified a region of the posterior superior temporal sulcus that is preferentially activated in the interpretation of facial expressions.[23] Similarly, another study found that transcranial magnetic stimulation disrupted the neural response to faces, but not the neural response to bodies or objects.[24] The patterns of activations found in this study suggests that facial information is processed by projections in the right hemisphere from the posterior superior temporal sulcus, through the anterior superior temporal sulcus, and into the amygdala.[24] Another study showed that the resting-state functional connectivity between the right posterior superior temporal sulcus, the right occipital face area, early visual cortex, and bilateral superior temporal sulcus was positively correlated with each subject's ability to recognize facial expression.[25]

Face-voice audiovisual integration

Many studies have suggested that the posterior superior temporal sulcus is associated with the crossmodal binding of auditory and visual stimuli.[2] The activation of this posterior portion of the superior temporal sulcus was reported in the detection of audio-visual incongruences and in voice perception.[2] The posterior superior temporal sulcus has also been shown to be preferentially activated by lip reading.[26] An area of the right posterior superior temporal sulcus was characterized by a recent study by a stronger response to audiovisual stimuli compared to that of auditory or visual stimuli alone.[27] This study also identified this same region to preferentially activated in the processing of stimuli associated with people, such as faces and voices.[27] Another fMRI study found that the neural representations of audiovisual integration, non-verbal emotional signals, voice sensitivity, and face sensitivity are all localized to separate regions of the superior temporal sulcus.[28] Likewise, this study also noted that the area most sensitive to voice is located in the trunk section of the superior temporal sulcus, the area most sensitive to facial expressions is located in the posterior terminal ascending branch, and audiovisual integration of emotional signals occurs in regions that overlap with face and voice recognition areas at the bifurcation of the superior temporal sulcus.[28]

Biological motion

The superior temporal sulcus has been found to have a unique sensitivity to observable manifestations of movement understanding, which suggest that the superior temporal sulcus is heavily involved in the recognition of movements and gestures required for normal social information processing in humans.[2] In fMRI studies evaluating the interpretation of a point-light display that represents a moving human figure as a pattern of dots, a cluster of significant brain activity was observed in the posterior superior temporal sulcus of the right hemisphere in subjects that correctly identified the biological motion being shown in the point-light display.[29] Furthermore, movement perception and movement interpretation is suggested to be localized in different regions of the superior temporal sulcus, with movement perception being processed in a posterior region of the superior temporal sulcus and movement understanding being processed in a more anterior region.[29]

Neurological disorders

In studies on dysfunctional social cognition in neurological disorders, such as what is observed in people with high-functioning autism, the role of the superior temporal sulcus in processing social information has been identified as the mechanism that lies at the root of these impairments in social interpretation.[30]

Autism and schizophrenia

Children with high-functioning autism have been reported to have no significant change in superior temporal sulcus activation for biological motion compared to non-biological motion, which suggests that the superior temporal sulcus is not specifically activated in the processing of biological motion like it is in children without autism.[30] In subjects with schizophrenia, another neurological disorder associated with significant impairments to social cognition, these social impairments have been linked to an alteration in posterior superior temporal sulcus activation in affective theory of mind, emotional recognition, and the interpretation of neutral facial expressions.[31] More specifically, it was determined that schizophrenic subjects exhibited hyperactivity within the posterior superior temporal sulcus of the right hemisphere in processing neutral facial expressions, but they also exhibited hypoactivity within this same region for emotional recognition and affective theory of mind.[31] This same study also found impaired connectivity between the right and left hemispheres of the posterior superior temporal sulcus in the processing of affective theory of mind.[31] Another recent study showed an inverse relationship between glutamate concentrations within the superior temporal sulcus and neuroticism scores assessed by questionnaire was found in subjects with schizophrenia, which suggests that elevations in glutamate concentrations may act as a compensatory mechanism that allows those with schizophrenia to prevent neuroticism.[32]

Agnosia

Various disorders of the STS have been documented in which patients fail to recognize a certain stimulus, but still exhibit subcortical processing of the stimulus, this is known as an agnosia.

Furthermore, agnosia is often linked to experiencing hardship in regard to stimuli recognition despite presenting otherwise normal or intact sensory functioning. Agnosia is found to disturb higher-order centers of the brain which also include cortical regions such as the posterior parietal cortex and occipitotemporal regions.[33][34]

Pure auditory agnosia (agnosia without aphasia) is found in patients who can't identify non-speech sounds such as coughing, whistling, and crying but have no deficit in speech comprehension. Speech agnosia is known as an incapability to comprehend spoken words despite intact hearing, speech production, and reading ability. Patients show a recognition of the familiarity of a word, but are not able to recall its meaning. Phonagnosia is characterized as an inability to recognize familiar voices, while having other auditory abilities. Patients exhibited a double dissociation with either an inability to match names or faces with a certain famous voice, or to discriminate familiar voices from unfamiliar ones. Visual agnosia can be broken into separate disorders in regard to what is being recognized.[35] An inability to recognize written words is known as alexia or word blindness, while an inability to recognize familiar faces is known as prosopagnosia. Prosopagnosia has been shown to have a similar double dissociation as phonagnosia in that some patients show an impairment of memory for familiar faces while others show impairment when discriminating familiar faces from unfamiliar ones.

______________________________________________________________________________

Dual Pathway Model:

Gregory Hickok and David Poeppel's model proposed what is known as the dual pathway or the dual-stream model. This model explores the perception and experience of speech stimuli. The model implies that two streams process information at the perception of speech - the ventral and dorsal stream. The ventral stream aids in the comprehension and recognition of speech input passing through the ears and entering the brain. On the other hand, the dorsal stream allows an individual to respond to said input as the speech stimuli further undergoes processing by the superior temporal gyrus. This correlates to the superior temporal sulcus because the dual pathway model occurs next after “spectrotemporal analysis” is carried out through the auditory cortex.[36][37]

Determination of Speech versus Non-Speech:

The superior temporal sulcus has an important part in the processing of human speech - specifically comprehension and perception of human voices/spoken language. According to “The superior temporal sulcus” (Howard 2023), research studies have been conducted by Blinder (2000) and Beline (2000) that examine the way in which the superior temporal sulcus reacts to various forms of stimuli especially speech and non-speech stimuli. Results show that the superior temporal sulcus is favorable towards response to human voices.[36][38]

Phonological Neighborhoods:

Phonological neighborhoods are “neighborhoods” or groups of words that all have common or similar sounds. Research shows how much the superior temporal sulcus plays a vital role in processing and understanding of phonological neighborhoods. Words experience classification based on the amount of other words with similar sounds. High neighborhood density words describe words that are similar phonetically to several other words. On the other hand, low neighborhood density describes words that have few similar sounding words.[39][40]

______________________________________________________________________________