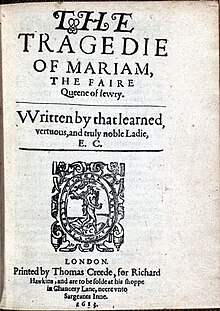

Title page of Elizabeth Cary's The Tragedy of Mariam. | |

| Author | Elizabeth Cary |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Tragedy |

| Set in | Judea, 29 B.C. |

| Publisher | printed by Thomas Creede for Richard Hawkins |

Publication date | 1613 |

The Tragedy of Mariam, the Fair Queen of Jewry is a Jacobean-era drama written by Elizabeth Cary, Viscountess Falkland, and first published in 1613. There is some speculation that Cary may have written a play before The Tragedy of Mariam that has since been lost, but most scholars agree that The Tragedy of Mariam is the first extant original play written by a woman in English.[1] It is also the first known English play to closely explore the history of King Herod's marriage to Mariamne.[2]

The play was written between 1602 and 1604.[3] It was entered into the Stationers' Register in December 1612. The 1613 quarto was printed by Thomas Creede for the bookseller Richard Hawkins. Cary's drama belongs to the subgenre of the Senecan revenge tragedy, which is made apparent by the presence of the classical style chorus that comments on the plot of the play, the lack of violence onstage, and "long, sententious speeches".[4] The primary sources for the play are The Wars of the Jews and The Antiquities of the Jews by Josephus, which Cary used in Thomas Lodge's 1602 translation.

The printed edition of Cary's play includes a dedication to Elizabeth Cary.[5] It is unknown whether this refers to the sister of Cary's husband, Henry Cary, or the wife of his brother Philip Cary.[5]

The play is then preceded by an invocation to the goddess Diana:

When cheerful Phoebus his full course hath run,

His sister's fainter beams our hearts doth cheer:

So your fair brother is to me the sun,

And you his sister as my moon appear.

You are my next belov'd, my second friend,

For when my Phoebus' absence makes it night,

Whilst to th'antipodes his beams do bend,

From you, my Phoebe, shines my second light.

He like to Sol, clear-sighted, constant, free,

You Luna-like, unspotted, chaste, divine:

He shone on Sicily, you destin'd be

T'illumine the now-obscurèd Palestine.

My first was consecrated to Apollo,

My second to Diana now shall follow.[6]

Scholars have suggested that the last two lines of the invocation, "My first was consecrated to Apollo; / My second to Diana now shall follow" support the argument that Cary may have written a play previous to The Tragedy of Mariam.[5]

The Tragedy of Mariam tells the story of Mariam, the second wife of Herod the Great, King of Judea from 39 to 4 B.C. The play opens in 29 B.C., when Herod is thought dead at the hand of Octavian (later Emperor Augustus).

Act I

Act II

Act III

Act IV

Act V

The Tragedy of Mariam was directed by Stephanie Wright for Tinderbox Theatre Co. at the Bradford Alhambra Studio, 19–22 October 1994.

The Tragedy of Mariam, Fair Queen of Jewry was directed by Liz Schafer at the Studio Theatre, Royal Holloway and Bedford New College, October 1995 (two performances).[9]

Mariam was directed by Becs McCutcheon for Primavera at the King's Head Theatre, Islington, 22 July 2007.

The Tragedy of Mariam, Faire Queene of Jewry was directed by John East, 28 June 2012, Central School of Speech and Drama, London.

On 14 March 2013, The Tragedy of Mariam was produced by the Improbable Fictions staged reading series in Tuscaloosa, Alabama.[10] It was directed by Kirstin Bone, produced by Nicholas Helms, and starred Miranda Nobert, Glen Johnson, Deborah Parker, Steve Burch, Michael Witherell, and Lauren Liebe.

The Mariam Project - Youth and Young Girlhood was directed by Becs McCutcheon for Burford Festival 2013, 12 June 2013 at St John the Baptist Church, Burford, Oxfordshire.[11] The designer was Talulah Mason.[12]

Lazarus Theatre Company performed The Tragedy of Mariam at the Tristan Bates Theatre in London's Covent Garden, in a version by director Gavin Harrington-Odedra, 12–17 August 2013.

The Mariam Pop Up installation was at the Gretchen Day Gallery, Peckham South London, 13 August 2013, directed by Rebecca McCutcheon and designed by Talulah Mason.[13]

The Tragedy of Mariam, a cut-down version of the play, was performed on Shakespeare's Globe stage on 7 December 2013, directed by Rebecca McCutcheon.[14]

The Tragedy of Mariam, a full cast audio adaptation of the play, was released on the Beyond Shakespeare podcast on 13th January 2023, produced by Robert Crighton. [15]

The story of Herod and Mariam would have been obscure to most English audiences, which makes Cary's choice of inspiration a point of interest for many scholars.[4] The play received only marginal attention until the 1970s, when feminist scholars recognized the play's contribution to English literature. Since then the play has received much more scholarly attention.[16]

While some continue to argue that The Tragedy of Mariam was not written to be performed, and that because it was not intended for the stage, much of the action in the play is described through dialogue rather than shown,[2] others, such as Alison Findlay, have argued the play could have been staged at a great house associated with Cary’s family such as Burford Priory, Ditchley, or Berkhamstead.[17] Indeed Stephanie Wright, who has directed the play, argues that action is often important in the play, in particular

The presentation of the ‘poison’ cup to Herod, the sword fight between Constabarus and Silleus, and the physical vacillation of Herod’s soldiers, with Mariam as their prisoner, as they respond to Herod’s constantly changing orders, are actions which need physical representation.[18]

Elizabeth Schafer points out that the opening of 4.1., Herod’s first entrance, has the stage direction ‘Enter Herod and his attendants’ and that given that the attendants subsequently say nothing, this stage direction is primarily visual or physical, that is, evidence of a theatrical rather than a readerly imagination.[19]

Critics who believe that Mariam is a closet drama argue that this form allowed women to exercise a form of agency without disrupting the patriarchal social order, and that they were able to "use closet activity to participate directly in the theater"[20] since they were forbidden from participating in stage theatre. The close links between closet drama's and conduct literature were able to disguise potentially more transgressive ideas, such as the proto-feminist ideas of female liberation proposed by the play's antagonist, Salome.

Critics often address the theme of marriage in Cary's play, such as how Mariam's tumultuous marriage may have been written as a response by Cary to her own relationship with her husband. Mariam is caught between her duty as a wife and her own personal feelings, much as Cary might have been, as a Catholic-leaning woman married to a Protestant husband.[4]

The theme of female agency and divorce is another common topic for critics. For example, some critics focus on Salome, who divorces her husband of her own will in order to be with her lover, Silleus.[4] Though Mariam is the title character and the play's moral center, her part in the play amounts to only about 10% of the whole.[21]

Tyranny is another key theme. Cary uses a Chorus and a set of secondary characters to provide a multi-vocal portrayal of Herod's court and Jewish society under his tyranny.[22]

In addition, though the racialized aspects of this play are often overlooked by many critics, the theme of race, both as it pertains to feminine beauty standards and religious politics is another key theme in this tragedy.[citation needed]