Ethnic background

Pre-Arab

Historically, Andalusians trace their earliest origins to the ancient civilization of Tartessos and it's inhabitants (the Tartessians), who were native to the Guadalquivir valley (historic region/province of Tarshish). Tartessos arose from extensive colonization and constant influence from the Semitic seafaring Phoenicians, who hailed from modern-day Lebanon. Intermixing was very common, and most Tartessians carried significant Near Eastern DNA. Following the fall of Phoenicia to the Assyrian Empire, Tartessos declined in prosperity, and merged with the non-Indo-European Iberians who dwelt to the east (becoming the Turdetani). During this period the Greeks began to colonize the Alboran coast, and had a moderate influence over the Turdetanian people.

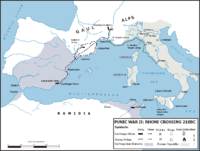

Phoenician influence was restored following the rise of the Carthaginian Empire, who made Andalusia the center of Punic (Phoenician-Berber) culture. A generally rapid assimilation between the Carthaginian and Turdetanian people took place, most likely caused by both groups having a partial Phoenician origin. As a powerful economic trading society, the Carthaginians used Andalusia (and the rest of their Iberian territory) as a physical bridge between North Africa and Europe, while also as a gateway for trade between North Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. Hundreds of years of Punic rule allowed a Hispano-Carthaginian culture to flourish and a distinct identity to form. Despite being a mixed society of Turdetani, Berbers, Phoenicians, and Greeks, they viewed themselves as Punics, bound by similar Levantine customs and traditions, and equated being a "Carthaginian" with citizenship and not ethnicity. During this time the Carthaginians maintained and strengthened the colonies on the Atlantic coast of North Africa (in the present day province of Arrif), while culturally, economically, and ethnically connecting the extreme south-west of Europe (provinces of Tarshish and Granada) and the extreme north-west of Africa (Arrif).

After years of warring, the Romans defeated the Punics and took control of the Iberian peninsula. The Romans called the peninsula Hispania (translated literally "Spain") and in 197 BC created the province of Hispania Ulterior ("further Spain"). Hispania Ulterior brought great wealth to the Republic and later Empire. The citizens were granted full citizenship, and the area was thoroughly and heavily Romanized. Historians noted that the Hispano-Carthaginian's civilized and advanced culture easily assimilated within the Empire, as they shared the similar ideals of trade and knowledge. The province of Hispania Ulterior evolved into the province of Baetica. Outside of Italy, Baetica was the most heavily colonized region of the entire Empire, nearly doubling it's population with Roman settlers. Their influence became one of the pillars of Andalusian identity, with Mozarabic (descended from Vulgar Latin brought by the Romans) being the most popular language spoken by Catholic Andalusian Mozarabs today. Andalusian Catholics (Mozarabs) have a strong connection to the Roman period, with the settlers bringing their religion to the peninsula. Although some claim direct descent from the Roman-Punic citizens of Baetica, genetic testing has revealed that Mozarabs have a significant amount of Converso (Berber and Arab converts to Christianity) DNA.

Following the destruction of the Western Roman Empire, tribes and peoples throughout Eurasia began to migrate across Europe, some of them settling in the Iberian Peninsula. Migrating from Scandinavia in Northern Europe (specifically the Baltic Sea island of Gotland in Sweden), the Visigoths conquered Hispania and allowed the Germanic Vandals to settle in Andalusia. The Vandals and Goths had a strict policy on not intermixing with the local population, and instead served as an elite ruling class. Although the Vandals would move on to settle in Numidia, the Visigoths occupied Andalusia for nearly 500 years. This allowed the different ethnic groups that colonized and settled Iberia (the Turdetani, Phoenicians, Romans, Berbers, and Greeks) to assimilate into one ethnic group, known as the Hispano-Romans. By the end of the Gothic reign, there were virtually no genetic/cultural distinction between Roman and pre-Roman Andalusians. The Germanic nobles had converted to Christianity and adopted Latin as their language, but by 700 BC, the Visigoths were struggling to keep a unified Kingdom together, and fighting among different nobles was common. The Goths also struggled to secure borders with the Germano-Celtic Kingdom of the Suevi to the west. As word of civil war traveled across the Strait of Gibraltar to North Africa, the Umayyad's saw it as a strategic time to invade Iberia and expand their Caliphate into Europe.

Arab

On July 19, 711, the Arab-Berber army had successfully conquered the Goths in Andalusia and the rest of the peninsula, and claimed it as a province of the Umayyad Caliphate (the capital being Cordoba), which was based in Damascus, Syria, and gave it the name al-Andalus, from which it derives today. The Visigoths, along with some Hispano-Roman forces, fled for the Cantabrian Mountains in northern Iberia, where they would eventually carve out the last Christian entity left in Hispania. Meanwhile colonization of al-Andalus was commenced almost immediately, and distribution of this influx of immigrants was strategic. The Arab upper-class were settled in present-day Andalusia and the Mediterranean coast of Spain, while the Berbers (who made up the bulk of colonists) were scattered throughout the center (Spain) and west (Portugal) of the peninsula. The conquerors brought with them the Arabic language, which would later produce the Ibero-Arabic language family. Over time the dialects of Ibero-Arabic began to fracture and evolve into their own languages, the most prominent being Andalusian Arabic and the Yabisan language. During this time period the Berbers began to revolt, causing Damascus to send a Syrian army to quell them. However, the Berbers were successful, and the Syrians fled to Europe via the Strait of Gibraltar and into Andalusia, where they settled.

A change of power in the Middle East caused the province to declare independence as an emirate, known as the Emirate of Córdoba, led by the Umayyads. The emirate evolved into the Caliphate of Córdoba and entered what historians call Andalusia's "golden age"; becoming the world leader in arts, math, religion, and science, among others. A highly advanced society, the rulers of Cordoba openly accepted a population of different religions, with Muslim, Christian, and Jewish scholars learning and co-operating with each other. The Caliphate became the center of European philosophy, schooling, and technology, and was seeing unprecedented advancement in the religious, scientific, and art spheres. Muslims and Jews dominated Andalusia, with Christians occupying the working class and bottom strata. However, the early division between Muslims, Jews, and Christians was not an ethnic one, but rather a religious one. This meant that the pre-conquest people of Iberia adopted an ethnic identity that was tied to their religion, not genetic origins. The wealth and prosperity achieved by Muslim and Jewish families prompted many Christians to convert.

Eventually, ethnic distinctions began to emerge from the Caliphate. Moors were those of Muslim descent, this included Arabs, Berbers, Syrians, and Muladis (Hispano-Roman converts and Muslims with mixed Arab, Berber, and Hispano-Roman origins). Mozarabs, who were the native Christian Hispano-Romans (later becoming a minority due to conversion and immigration) adopted Arabic culture and customs, while their Latin language evolved into Mozarabic, which was so strongly influenced by Andalusian Arabic that it was even written in the Arabic script. Sephardis (also known as Sephardic Jews) appeared as a distinct ethnic group during this time. They comprised mixed genes of both original Levantine Jewish settlers and Hispano-Roman converts. Linguistically, all three ethnic groups spoke Andalusian Arabic, which evolved from Ibero-Arabic (and is in turn is descended from Maghrebi Arabic), as the lingua franca of Andalusian society. During the earlier years of the Caliphate the Mozarabs spoke Mozarabic, a Latin-derived equivalent of Arabic, written in the Arabic script. Over time however, most Mozarabs converted to Islam and intermixed with the Arab, Berber and Syrian Andalusians, giving rise to the ethnic group known as the Muladis (which made up 80 percent of the Andalusian population), who adopted Andalusian Arabic as their primary language. Sephardis were generally trilingual, being able to communicate in Andalusi Arabic, Mozarabic and Hebrew.

Civil war in the Caliphate caused it's fragmentation into small independent states ruled by Arab royalty. The population of these states were generally a mix of Muladis (Muslims with full or partial Hispano-Roman heritage), Arabs, Berbers, and Syrians. However their culture was predominantly Arab-derived, and contained strong Berber influences. Mozarabs became a minority in their respective homeland; many converted religions and married into al-Andalus's Muslim population, while most of the remaining Mozarabs fully embraced the Arabic language and culture. Only small pockets of the natives remained scattered throughout the taifas. In an effort to gain additional forces for their armies, the Arab royalty invited the Berber kingdoms of North Africa to intervene and assist in their wars. This plan failed, and instead the Berbers gained control over Andalusia, bringing to an end the "golden age" and marking a period of genocide, religious persecution, and forced conversions.

Berber