Bremmer, Jan N. (2006)

Brill's New Pauly

- s.v. Gorgo 1

- Female monster in Greek mythology. According to the canonical version of the myth (Apollod. 2,4,1-2), Perseus must get the head of Medusa, the mortal sister of Sthenno and Euryale (Hes. Theog. 276f.; POxy. 61, 4099), the daughters of Phorcys and Ceto (cf. Aeschylus' drama Phorcides, TrGF 262). The three sisters live on the island of Sarpedon in the ocean (Cypria, fr. 23; Pherecydes FGrH 3 F 11), although Pindar (Pyth. 10,44-48) located them among the Hyperboraeans ( Hyperborei). Their connection to the sea is still apparent in Sophocles (TrGF 163) and Hesychius (s.v. Gorgides). The Gorgos' terrifying shape (snake hair, fangs) transforms into stone whoever looks at them (their ugliness was so notorious that Aristoph. [Ran. 477] referred to the women of the Athenian deme Teithras as Gorgones). In the divine battle against the Titans, Athena also kills a G., whose blood was later attributed with the power to heal as well as to poison (Eur. Ion 989-991; 1003ff.; Paus. 8,47,5; Apollod. 3,10,3). With the aid of Athena, Hermes, and the Nymphs, who equipped him with winged sandals, Hades' helmet of invisibility, and a sickle (hárpē), Perseus is able to decapitate Medusa in her sleep (Pherecydes FGrH 3 F 11). From her neck rise Chrysaor [4] and the winged horse Pegasus. Perseus is pursued by Medusa's sisters, but he escapes and, in the end, turns his enemy Polydectes to stone by using G.'s head.

- The myth was already known to Hesiodus (Theog. 270-282) and shows oriental influences: the iconography of the G. has borrowed traits from Mesopotamian Lamaštu. Perseus saves Andromeda in Ioppe-Jaffa (Mela 1,64), and an oriental seal shows a young hero holding a hárpē and seizing a demonic creature [1. 83-87]. In Etruria, Perseus' adventure was already popular in the 5th cent. [3]. Roman authors like Ovidius (Men. 4,604-5,249) ─ who change Medusa into a stunningly beautiful young girl ─ and Lucan (9,624-733) focussed in particular on the frightening head of Medusa [cf. 4].

- In Mycenae, Perseus was seen in the context of initiation. His killing of Medusa reflects the testing of young warriors [2]. In fact, the descriptions of G.'s head recall certain elements of the archaic battle vehemence: the horrifying appearance, broad grin, grinding teeth, and powerful battle screams [6]. The popularity of G.'s head, the Gorgoneion, as attested on Athena's aegis and on warriors' shields (as early as Hom. Il. 5,741; 11,35-37) as well as in Aristoph. Ach. 1124, indicates the frightening effect and the protection of the Delphic omphalós (Eur. Ion 224) and the Delian thēsaurós (thesauros: IG XIV 1247) by the Gorgos. The myth of Perseus and Medusa is therefore an important example of the complex interrelation of narrative and iconographic motifs between Greece and the Orient during the archaic period.

Bremmer, Jan N. (2015)

Oxford Classical Dictionary

- s.v. Gorgo/Medusa

- Female monsters in Greek mythology. According to the canonical version of the myth (Apollod. 2. 4. 1–2) Perseus (1) was ordered to fetch the head of Medusa, the mortal sister of Sthenno and Euryale; through their horrific appearance these Gorgons turned to stone anyone who looked at them. With the help of Athena, Hermes, and nymphs, who had supplied him with winged sandals, Hades' cap of invisibility, and a sickle (harpē) Perseus managed to behead Medusa in her sleep; from her head sprang Chrysaor and the horse Pegasus. Although pursued by Medusa's sisters, Perseus escaped and, eventually, turned his enemy Polydectes to stone by means of Medusa's head.

Fowler

p. 254

- As often with the mythical geography of the edges of the world, there is confusion about the location of [Perseus' encounter with the Gorgons]. In He's. Th. 270-5, the Graiai, Gorgons, and Hesperides all live in the west, near Okeanos' springs (πηγαί, whence Pegasus, 282).

Gantz

p. 20

- Unlike the Graiai, the Gorgons are from the beginning (in Hesiod) three in number (Th 274-83). Hesiod names them Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa, and places them toward the edge of night, beyond Okeanos, near the Hesperides, in other words to the far west (he does not say whether the Graiai lived near them). Of the three, steno and Euryale are immortal and ageless, but Medousa is mortal (Hesiod offers no explanation of this odd situation). She alone mates with Poseidon (assuming Kyanochaites is here as elsewhere, an epithet of the sea god), and after her beheading by Perseus, Chrysaor and the horse Pegasos spring forth from her neck. ...

- In contrast ... The Aspis offers a typically garish portrait: Gorgons with twin snakes ... wrapped around their wastes ... and possibly a vague reference to snakes for hair (Aspis 229-37). Snaky locks are in any case well attested by Pindar (Py 10.46-48; 12.9-12), and here again Medousa's head lithifies, while Euryale's lament becomes the model for the song of the flute. In Pythian 10, we also see Perseus journeying to the land of the Hyperboreans in the far north on his quest for the head; the Gorgons may or may not have been located there. For Aeschylus, we must again be content with the description in Prometheus Desmotes, since there are no relevant fragments from the Phorkides. As noted above, his Gorgons live near their sister Graiai to the far east; they have wings and snaky hair, and no mortal can look upon them and live (PD 798-800). This last detail suggests that Aeschylus believed all three sisters could turn men to stone, but he may be exaggerating for effect, or perhaps he refers to their generally ferocious character. The tale that Medousa was once beautiful, and fell prey to Athena's anger by mating with Poseidon in the goddess' temple, first appears in Ovid (Met 4.790-803); something of the same sort also surfaces in [cont.]

p. 21

- Apollodorus, who says that Medousa wished to rival Athena in beauty (ApB 2.4.3). Such an idea may have developed at some late point in time to dignify Posiedon's union with the Gorgon; certainly it will not explain the equally hideous condition of her two sisters.

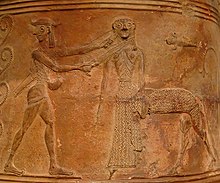

- Artistic representations of Gorgons are much too abundant to list in detail here, ... On a Boiotian relief amphora of c. 650 B.C., a figure in traveling garb cuts off the head of a female represented as a Kentauros (Louvre CA 795).25 The attitude of the beheader, with face averted from his victim, seems not only to guarantee that this is an early Medousa, but to offer our earliest evidence for the Gorgon's perilous qualities. On the contemporary Protoattic Eleusis Amphora, the sisters appear as monstrous (albeit shapely) inset-faced creatures with no wings but distinct snakes around their heads (Eleusis, no #). By the time of the name vases of Nessos and Gorgon Painters of Athens (end of the seventh century: Athens 1002, Louvre E874), canonical features, such as the tripartite nose and lolling tongue (perhaps developed in Corinthian painting), are basically in force; for the wings and snakes there is also a slightly earlier ivory relief from Santos depicting the decapitation (Samos E 1).

Tripp

s.v. Gorgons

- Three Snaky-haired monsters, named Steno, Euryale, and Medusa. Euripides says that Ge brought forth "the Gorgon" to aid her children, the Giants, in their war with the gods. Others claim that the Gorgons were among the brood that sprang from the union of the ancient sea-god Phorcys and his sea-monster sister, Ceto; these offspring included Echidna, Ladin, and the Graeae. The Gorgons had brazen hands and wings of gold; red tongues lolled from their mouths between tusks like those of swine; and serpents writhed about their heads. Their faces were so hideous that a glimpse of them would turn man or beast to stone. Of the three, only Medusa was mortal. She was killed by Perseus. [Hesiod, Theogony, 270-283. See also references un der PERSEUS.]

West

Cypria fr. 30 West [= fr. 32 Bernabé]

- 30 Herodian. περὶ μονήρους λέξεως 9(ii. 914.15 L.)

- 30 Herodian, On Peculiar Words

- And Sarpedon in the special sense of the island in Oceanus, where the Gorgons live, as the author of the Cypria says:

- And she conceived and bore him the Gorgons, dread creatures, who dwelt on Sarpedon on the deep-swirling Oceanus, a rocky island.