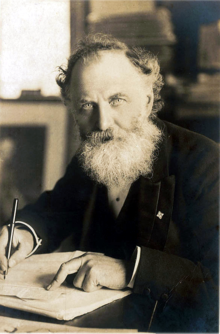

William Thomas Stead | |

|---|---|

Photo portrait by E. H. Mills, 1905 | |

| Born | 5 July 1849 Embleton, Northumberland, England |

| Died | 15 April 1912 (aged 62) |

| Monuments |

|

| Nationality | English |

| Education | Silcoates School |

| Occupation | Newspaper editor |

| Notable work | The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon |

| Style | Sensationalism |

William Thomas Stead (5 July 1849 – 15 April 1912) was an English newspaper editor who, as a pioneer of investigative journalism, became a controversial figure of the Victorian era.[1] Stead published a series of hugely influential campaigns whilst editor of The Pall Mall Gazette, including his 1885 series of articles, The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon. These were written in support of a bill, later dubbed the "Stead Act", that raised the age of consent from 13 to 16.[2]

Stead's "new journalism" paved the way for the modern tabloid in Great Britain.[2] He has been described as "the most famous journalist in the British Empire".[3] He is considered to have influenced how the press could be used to influence public opinion and government policy, and advocated "Government by Journalism".[4] He was known for his reportage on child welfare, social legislation and reformation of England's criminal codes.

Stead died in the sinking of the RMS Titanic.[2]

Stead was born in Embleton, Northumberland on July 5, 1849, the son of the Reverend William Stead, a poor and respected Congregational minister, and Isabella (née Jobson), a cultivated daughter of a Northumberland farmer, John Jobson of Warkworth.[4][5][6] A year later the family moved to Howdon on the River Tyne,[7] where his younger brother, Francis Herbert Stead, was born. Stead was largely educated at home by his father, and by the age of five he was already well-versed in the Holy Scriptures and is said to have been able to read Latin almost as well as he could read English.[8] It was Stead's mother who perhaps had the most lasting influence on her son's career. One of Stead's favourite childhood memories was of his mother leading a local campaign against the government's controversial Contagious Diseases Acts – which required prostitutes living in garrison towns to undergo medical examination.[9]

From 1862 to 1864, he attended Silcoates School in Wakefield until he was apprenticed to a merchant's office on the Quayside in Newcastle upon Tyne, where he became a clerk.[10]

Stead contributed articles to the fledgling liberal Darlington newspaper The Northern Echo from 1870 and despite his inexperience was appointed editor of the newspaper in 1871.[11] Aged just 22 Stead was the youngest newspaper editor in the country.[9] Stead used Darlington's excellent railway connections to his advantage, increasing the newspaper's distribution to national levels.[8] Stead was always guided by a moral mission, influenced by his faith, and wrote to a friend that the position would be "a glorious opportunity of attacking the devil".[11]

In 1873 he married his childhood sweetheart, Emma Lucy Wilson, the daughter of a local merchant and shipowner; they would eventually have six children.[12] In 1876 Stead joined a campaign to repeal the Contagious Diseases Act, befriending the feminist Josephine Butler. The law was repealed in 1886.[13]

He gained notoriety in 1876 for his coverage of the Bulgarian atrocities agitation.[14] He is also credited as "a major factor" in helping William Ewart Gladstone win an overwhelming majority in the 1880 general election.[4][15]

Stead was appointed assistant editor of the Liberal Pall Mall Gazette[16] (a forerunner of the London Evening Standard) in 1880, and he helped transform a traditionally conservative newspaper "written by gentlemen for gentlemen".[9] When its editor, John Morley, was elected to Parliament, Stead took over the role (1883–1889). When Morley was made Secretary of State for Ireland, Gladstone asked the new cabinet minister if he were confident that he could deal with that most distressful country. Morley replied that, if he could manage Stead, he could manage anything.

Over the next seven years Stead would develop what Matthew Arnold dubbed "The New Journalism".[12] His innovations as editor of the Gazette included incorporating maps and diagrams into a newspaper, breaking up longer articles with eye-catching subheadings and blending his own opinions with those of the people he interviewed.[9] He made a feature of the Pall Mall extras, and his enterprise and originality exercised a potent influence on contemporary journalism and politics.[16] Stead's first sensational campaign was based on a Nonconformist pamphlet, The Bitter Cry of Outcast London. His lurid stories of squalid life in the slums had a wholly beneficial effect on the capital. A Royal Commission recommended that the government should clear the slums and encourage low-cost housing in their place. It was Stead's first success. He also pioneered the use of the interview in British journalism—although other interviews had appeared in British papers before[17]—with his interview with General Gordon in 1884.[18]

In 1884 Stead pressured the government to send his friend General Gordon to the Sudan to protect British interests in Khartoum. The eccentric Gordon disobeyed orders, and the siege of Khartoum, Gordon's death and the failure of the hugely expensive Gordon Relief Expedition amounted to one of the great imperial disasters of the period.[13] After General Gordon's death in Khartoum in January 1885, Stead ran the first 24-point headline in newspaper history, ‘TOO LATE!’, bemoaning the relief force's failure to rescue a national hero.[19]

During the following year he managed to persuade the British government to supply an additional £51⁄2million to bolster weakening naval defences, after which he published a series of articles.[15] Stead was not a hawk, instead believing Britain's strong navy was necessary to maintain world peace.[20] He distinguished himself in his vigorous handling of public affairs and his brilliant modernity in the presentation of news.[16] However he is also credited with originating the modern journalistic technique of creating a news event rather than just reporting it, as his most famous ‘investigation’, the Eliza Armstrong case, was to demonstrate.[21]

In 1886 he began a campaign against Sir Charles Dilke, 2nd Baronet, over his nominal exoneration in the Crawford scandal. The campaign ultimately contributed to Dilke's misguided attempt to clear his name and his consequent ruin. Stead employed Virginia Crawford, and she developed a career as a journalist and writer, researching for other Stead authors, but never wrote on her own case or Dilke in any way.[22]

|

Main article: Eliza Armstrong case |

In 1885, in the wake of Josephine Butler's fight for the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts, Stead entered upon a crusade against child prostitution by publishing a series of four articles entitled ‘The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon’. As part of his investigation he arranged the ‘purchase’ of Eliza Armstrong, the 13-year-old daughter of a chimney sweep. In his subsequent articles Stead referred to Eliza as "Lily." Her real name came out during Stead's trial for procuring.[23]

The first of his four articles was trailed with a warning guaranteed to make the Pall Mall Gazette sell out. Copies changed hands for 20 times their original value and the office was besieged by 10,000 members of the public.[24] The popularity of the articles was so great that the Gazette's supply of paper ran out and had to be replenished with supplies from the rival Globe.[9]

Though his action is thought to have furthered the passing of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, his successful demonstration of the existence of the trade led to his conviction for abduction and a three-month term of imprisonment at Coldbath Fields and Holloway prisons. He was convicted on technical grounds that he had failed to first secure permission for the ‘purchase’ from the girl's father.

The ‘Maiden Tribute’ campaign was the high point in Stead's career in daily journalism.[4] The series inspired George Bernard Shaw to write Pygmalion and to name his lead character Eliza.[9] Another of the characters described, the ‘Minotaur of London’, has been suggested as having inspired Jekyll and Hyde.[25]

Stead resigned his editorship of the Pall Mall in 1889 in order to found the Review of Reviews (1890) with Sir George Newnes. It was a highly successful non-partisan monthly.[4] The journal found a global audience and was intended to bind the empire together by synthesising all its best journalism.[13] Stead's abundant energy and facile pen found scope in many other directions in journalism of an advanced humanitarian type. This time saw Stead "at the very height of his professional prestige", according to E. T. Raymond.[10] He was the first editor to employ female journalists.[13]

Stead lived in Chicago for six months in 1893-4, campaigning against brothels and drinking dens, and published If Christ Came to Chicago.[13]

Beginning in 1895, Stead issued affordable reprints of classic literature under such titles as The Penny Poets[26] and Penny Popular Novels, in which he "boil[ed] down the great novels of the world so that they might fit into, say, sixty-four pages instead of six hundred".[27] His ethos behind the venture pre-dated Allen Lane's Penguin Books by nearly forty years, and he became "the foremost publisher of paperbacks in the Victorian Age".[15] In 1896, Stead launched the series Books for the Bairns, whose titles included fairy tales and works of classical literature.[28][15][29]

Stead became an enthusiastic supporter of the peace movement, and of many other movements, popular and unpopular, in which he impressed the public generally as an extreme visionary, though his practical energy was recognised by a considerable circle of admirers and pupils.[16] Stead was a pacifist and a campaigner for peace, who favoured a "United States of Europe" and a "High Court of Justice among the nations" (an early version of the United Nations), yet he also preferred the use of force in the defence of law.[30][31] He extensively covered the Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907; for the latter he printed a daily paper during the four-month conference. He has a bust at the Peace Palace in The Hague. As a result of these activities, Stead was repeatedly nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.[8]

With all his unpopularity, and all the suspicion and opposition engendered by his methods, his personality remained a forceful one, in both public and private life. He was an early imperial idealist, whose influence on Cecil Rhodes in South Africa remained of primary importance; many politicians and statesmen, who on most subjects were completely at variance with his ideas, nevertheless owed something to them. Rhodes made him his confidant, and was inspired in his will by his suggestions; and Stead was intended to be one of Rhodes's executors. However, at the time of the Second Boer War Stead threw himself into the Boer cause and attacked the government with characteristic violence,[16] and consequently his name was removed from the will's executors.[32]

The number of his publications gradually became very large, as he wrote with facility and sensationalist fervour on all sorts of subjects, from The Truth about Russia (1888) to If Christ Came to Chicago! (Laird & Lee, 1894), and from Mrs Booth (1900) to The Americanisation of the World[33] (1901).[16]

Stead was an Esperantist, and often supported Esperanto in a monthly column in Review of Reviews.[34]

In 1904 he launched The Daily Paper, which folded after six weeks, and Stead lost £35,000 of his own money (almost £3 million in 2012 value) and suffered a nervous breakdown.[7][13]

A year before the Spanish–American War W. T. Stead travelled to New York to meet William Randolph Hearst, to teach him government by journalism.[35][36][self-published source][37]

In 1905 Stead travelled to Russia to try to discourage violence during the Russian Revolution, but his tour and talks were unsuccessful.[38]

In the 1890s, Stead became increasingly interested in spiritualism.[39] In 1893, he founded a spiritualist quarterly, Borderland, in which he gave full play to his interest in psychical research.[7][39] Stead was editor, and he employed Ada Goodrich Freer as assistant editor; she was also a substantial contributor under the pseudonym "Miss X".[40] Stead claimed that he was in the habit of communicating with Freer by telepathy and automatic writing.[41][42][43] The magazine ceased publication in 1897.[39]

Stead claimed to be in receipt of messages from the spirit world and, in 1892, to be able to produce automatic writing.[39][41] His spirit contact was alleged to be the departed Julia A. Ames, an American temperance reformer and journalist whom he met in 1890 shortly before her death. In 1909, he established Julia's Bureau, where inquirers could obtain information about the spirit world from a group of resident mediums.[39]

Grant Richards said that "The thing that operated most strongly in lessening Stead's hold on the general public was his absorption in spiritualism".[44]

The physiologist Ivor Lloyd Tuckett wrote that Stead had no scientific training and was credulous when it came to the subject of spiritualism. Tuckett examined a case of spirit photography that Stead had claimed was genuine. Stead visited a photographer who produced a photograph of him with an alleged deceased soldier known as "Piet Botha". Stead claimed the photographer could not have come across any information about Piet Botha; however, Tuckett discovered that an article in 1899 had been published on Pietrus Botha in a weekly magazine with a portrait and personal details.[45]

In the early 20th century, Arthur Conan Doyle and Stead were duped into believing that the stage magicians Julius and Agnes Zancig had genuine psychic powers. Both Doyle and Stead wrote the Zancigs performed telepathy. In 1924 Julius and Agnes Zancig confessed that their mind reading act was a trick and published the secret code and all the details of the trick method they had used under the title of Our Secrets!! in a London newspaper.[46]

Ten years after the Titanic went down, Stead's daughter Estelle published The Blue Island: Experiences of a New Arrival Beyond the Veil,[47] which purported to be a communication with Stead via a medium, Pardoe Woodman. In the book, Stead described his death at sea and discussed the nature of the afterlife. The manuscript was produced using automatic writing, and Ms. Stead cited as proof of its authenticity the writer's habit of going back to cross "t's" and dot "i's" while proof-reading, which she said was characteristic of her father's writing technique in life.

Stead boarded the Titanic for a visit to the United States to take part in a peace congress at Carnegie Hall at the request of President William Howard Taft. Survivors of the Titanic reported very little about Stead's last hours. He chatted enthusiastically through the 11-course meal that fateful night, telling thrilling tales (including one about the cursed mummy of the British Museum), but then retired to bed at 10.30 pm.[13] After the ship struck the iceberg, Stead helped several women and children into the lifeboats, in an act "typical of his generosity, courage, and humanity", and gave his life jacket to another passenger.[4]

A later sighting of Stead, by survivor Philip Mock, has him clinging to a raft with John Jacob Astor IV. "Their feet became frozen", reported Mock, "and they were compelled to release their hold. Both were drowned."[48] William Stead's body was not recovered.

Stead had often claimed that he would die from either lynching or drowning.[4] He had published two pieces that gained greater significance in light of his fate on the Titanic. On 22 March 1886, he published an article titled "How the Mail Steamer went down in Mid Atlantic by a Survivor",[49] wherein a steamer collides with another ship, resulting in a high loss of life due to an insufficient ratio of lifeboats to passengers. Stead had added: "This is exactly what might take place and will take place if liners are sent to sea short of boats". In 1892, Stead published a story titled "From the Old World to the New",[50] in which a vessel, the Majestic, rescues survivors of another ship that collided with an iceberg.

Following his death, Stead was widely hailed as the greatest newspaperman of his age. His friend Viscount Milner eulogised Stead as "a ruthless fighter, who had always believed himself to be 'on the side of angels'".[51]

His sheer energy helped to revolutionise the often stuffy world of Victorian journalism, while his blend of sensationalism and indignation set the tone for British tabloids.[52] Like many journalists, he was a curious mixture of conviction, opportunism and sheer humbug. According to his biographer W. Sydney Robinson, "He twisted facts, invented stories, lied, betrayed confidences, but always with a genuine desire to reform the world – and himself." According to Dominic Sandbrook, "Stead's papers forced his readers to confront the seedy underbelly of their own civilisation, but the editor probably knew more about that dark world than he ever let on. He held up a mirror to Victorian society, yet deep down, like so many tabloid crusaders, he was raging at his own reflection."[19]

According to Roy Hattersley, Stead became "the most sensational figure in 19th-century journalism".[53]

A memorial bronze was erected in Central Park, New York City, in 1920. It reads, "W. T. Stead 1849–1912. This tribute to the memory of a journalist of worldwide renown is erected by American friends and admirers. He met death aboard the Titanic April 15, 1912, and is numbered amongst those who, dying nobly, enabled others to live." A duplicate bronze is located on the Thames Embankment not far from Temple, where Stead had an office.

A memorial plaque to Stead can also be seen at his final home, 5 Smith Square, where he lived from 1904 to 1912. It was unveiled on 28 June 2004 in the presence of his great-great-grandson, 13-year-old Miles Stead. The plaque was sponsored by the Stead Memorial Society.[54]

In his native Embleton, a road has been named "W T Stead Road".

In his adopted Darlington a pub is named in his honour in the town centre.

In the 2009 video game Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors, Stead's 'How the Mail Steamer Went Down in Mid Atlantic by a Survivor, From the Old World to the New and his death on the Titanic are discussed by Akane Kurashiki and Junpei, who debate the possibility that Stead was undergoing automatic writing by connecting to his future self.

Fourteen boxes of the papers of William Thomas Stead are held at the Churchill Archives Centre in Cambridge.[55][56] The bulk of this collection comprises Stead's letters from his many correspondents, including Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, William Gladstone and Christabel Pankhurst. There are also papers and a diary relating to his time spent in Holloway Prison in 1885 and to his many publications.[citation needed]

Papers of William Thomas Stead are also held at The Women's Library at the Library of the London School of Economics,[57][58]

Charles Barker Howdill (1863–1941) took a colour photograph of Stead "finished in 12 minutes" on 17 January 1912, about three months before Stead's death. It is now in the collections of Leeds Museums and Galleries.[59]