peeweee hahahahahahahahhahahahahhahahahahhahahahahhahahahajahhahshshajdckfkfkdj

| successor=Andrew Johnson

|state2=Illinoisss,dksiididkrisjkdick

|district2=7th

|term_start2=March 4, 1847

|term_end2=March 4, 1849

|predecessor2=John Henry

|successor2=Thomas Harris

|state_house3=Illinois

| birth_date=February 12, 1809

| birth_place=Hodgenville, Kentucky, U.S.

| death_date=April 15, 1865 (aged 56)

| death_place=Washington, D.C.

| spouse=Mary Todd Lincoln

| party=Republican and Whig

| vicepresident=Hannibal Hamlin (1861 to 1865);

Andrew Johnson (March — April 1865)

| height=6 ft 4 in (1.93 m)

| signature=Abraham Lincoln signature.JPGkdkfjdjjdjfjfifjfhghfudiddudjsu

))

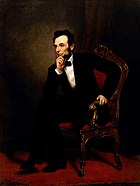

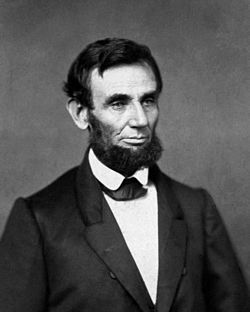

Abraham Lincoln (February 12 1809 – April 15 1865) was the 16th President of the United States. He served as president from 1861 to 1865, during the American Civil War. Just five days after most of the Confederate forces had surrendered and the war was ending, John Wilkes Booth assassinated Lincoln. Lincoln was the first president of the United States to be assassinated. Lincoln has been remembered as the "Great Emancipator" because he worked to end slavery in the United States.[1]

Life

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, in Hodgenville, Kentucky, U.S.. His parents were Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks. His family was very poor.[2] Abraham had one brother and one sister. His brother died in childhood. They grew up in a small log cabin house, with just one room inside. Although slavery was legal in Kentucky at that time, Lincoln's father, who was a religious Baptist, refused to own any slaves.

When Lincoln was seven years old, his family moved to Indiana. Later on they moved to Illinois.[3] In his childhood he helped his father on the farm, but when he was 22 years old he left home and moved to New Salem, Illinois, where he worked in a general store.[4] Later, he said that he had gone to school for just one year, but that was enough to learn how to read, write, and do simple math. In 1842, he married Mary Todd Lincoln. They had four children, but three of them died when they were very young.[5] Abraham Lincoln was sometimes called Abe Lincoln or "Honest Abe" after he ran miles to give a customer the right amount of change. The nickname "Honest Abe" came from a time when he started a business that failed. Instead of running away like many people would have, he stayed and worked to pay off his debt.[6]

Early political career

Lincoln started his political career in 1832 when he ran for the IGA Illinois General Assembly, but he lost the election. He served as a captain in the Illinois militia during the Black Hawk War, a war with Native American tribes. When he moved to Springfield in 1837, he began to work as a lawyer. Soon, he became one of the most highly respected lawyers in Illinois.[7][8] In 1837, as a member of the Illinois General Assembly, Lincoln issued a written protest of its passage of a resolution stating that slavery could not be abolished in Washington, D.C.[9][10]

In 1841, he won a court case (Bailey v. Cromwell). He represented a black woman who claimed she had already been freed and could not be sold as a slave. In 1847, he lost a case (Matson v. Rutherford) representing a slave owner (Robert Matson) claiming return of fugitive slaves. After he moved to Illinois, he worked as a shopkeeper and postmaster. He rode the circuit of courts for many years. When he was 21, he worked on a flatboat that carried freight. He joined the Independent Spy Corp. At first, he was a member of the Whig Party. He later became a Republican. Lincoln ran for senate against Stephen A. Douglas. Douglas won.

In 1846, Lincoln joined the Whig Party and was elected to one term in the House of Representatives. After that, he ignored his political career and instead worked as a lawyer. In 1854, in reaction to the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Lincoln became involved in politics again. He joined the Republican Party, which had recently been formed in opposition to the expansion of slavery. In 1858, he wanted to become senator; although this was unsuccessful, the debates drew national attention to him.[11] The Republican Party nominated him for the Presidential election of 1860.[12]

Presidency

Lincoln was chosen as a candidate for the elections in 1860 for different reasons. Among these reasons were that his views on slavery were less extreme than those of other people who wanted to be candidates. Lincoln was from what was then one of the Western states, and had a bigger chance of winning the election there. Other candidates that were older or more experienced than him had enemies inside the party.[13][14] Lincoln's family was poor, which added to the Republican position of free labor, the opposite of slave labor. Lincoln won the election in 1860, and was made the 16th President of the United States. He won with almost no votes in the South. For the first time, a president had won the election because of the large support he got from the states in the North.[14] During his presidency Lincoln became well-known because of his large stovepipe hat. He used his tall hat to store papers and documents when he was traveling.[15]

Lincoln and the Civil War

After Lincoln's election, seven States (South Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Texas and Louisiana) formed the Confederate States of America. When the United States refused to surrender Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, the Confederates attacked the fort, beginning the American Civil War. Later, four more states (Arkansas, Virginia, Tennessee, and North Carolina) joined the Confederacy for a total of eleven. In his whole period as President, he had to rebuild the Union with military force and many bloody battles. He also had to stop the "border states", like Kentucky, Missouri, and Maryland, from leaving the Union and joining the Confederacy.

Lincoln was not a general, and had only been in the army for a short time during the Black Hawk War.[16] However, he still took a major role in the war, often spending days and days in the War Department. His plan was to cut off the South by surrounding it with ships, control the Mississippi River, and take Richmond, the Confederate capital. He often clashed with generals in the field, especially George B. McClellan, and fired generals who lost battles or were not aggressive enough. Eventually, he made Ulysses S. Grant the top general in the army.

Emancipation Proclamation

With the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, Lincoln ordered the freedom of all slaves in those states still in rebellion during the American Civil War. It did not actually immediately free all those slaves however, since those areas were still controlled by the rebelling states of the Confederacy. Only a small number of slaves already behind Union lines were immediately freed. As the Union army advanced, nearly all four million slaves were effectively freed. Some former slaves joined the Union army. The Proclamation also did not free slaves in the slave states that had remained loyal to the Union (the federal government of the US). Neither did it apply to areas where Union forces had already regained control.[1] Until the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1865, only the states had power to end slavery within their own borders, so Lincoln issued the proclamation as a war measure.

The Proclamation made freeing the slaves a Union goal for the war, and put an end to movements in European nations (especially in Great Britain and France) that would have recognized the Confederacy as an independent nation. Lincoln then sponsored a constitutional amendment to free all slaves. The Thirteenth Amendment, making slavery illegal everywhere in the United States, was passed late in 1865, eight months after Lincoln was assassinated.

Gettysburg Address

Lincoln made a famous speech after the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863 called the Gettysburg Address. The battle was very important, and many soldiers from both sides died. The speech was given at the new cemetery for the dead soldiers. It is one of the most famous speeches in American history.[17]

Second term and assassination

Lincoln was reelected president in 1864 and re-inaugurated March 4 1865. Soon afterwards, it appeared likely that the Union would win the Civil War. Lincoln proposed lenient terms for restoring self-government in the states that had rebelled. On April 9 1865, the leading Confederate general, Robert E. Lee, surrendered his armies. On April 11, 1865, Lincoln gave a speech in which he promoted voting rights for blacks.[18]

On April 14th, Lincoln went to attend a play with his wife at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C.. During the third act of the play, John Wilkes Booth, a well-known actor and a Confederate spy from Maryland, entered the presidential box and shot Lincoln at point-blank range,[19] mortally wounding him. An unconscious Lincoln was carried across the street to Petersen House. He was placed diagonally on the bed because his tall frame would not fit normally on the smaller bed.[20] He remained in a coma for nine hours before dying the next morning.[21] Booth escaped, but died from shots fired during his capture on April 26.

Lincoln was the first American president to be assassinated.[22]

Legacy

Lincoln has been consistently ranked both by scholars[23] and the public[24] as one of the greatest U.S. presidents. He is often considered the greatest president for his leadership during the American Civil War and his eloquence in speeches such as the Gettysburg Address.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Lincoln". Yale University. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ↑ Thornton, Brian (October 31, 2005). 101 things you didn't know about Lincoln: loves and losses, political power. Adams Media. ISBN 9781593373993.

((cite book)): Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑

"Lincoln Trail Homestead State Park". Abraham Lincoln Online. Retrieved 2008-05-21s.

((cite web)): Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ↑ Fehrenbacher, Don (1989). Speeches and Writings 1859-1865. Library of America. p. 163.

- ↑ Goodwin, Doris Kearns (2005). Team of Rivals. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, Inc.

- ↑ White, Jr., Ronald C. (2009). A. Lincoln: A Biography. Random House, Inc. ISBN 9781400064991

- ↑ Frank, John (1991). Lincoln as a Lawyer. Americana House. ISBN 0962529028.

- ↑ "Biography of Lincoln". Quotable Lincoln. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

- ↑

"Lincoln on Slavery". Retrieved 2009-NOV-15.

((cite web)): Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ↑

"Protest in Illinois Legislature on Slavery". University of Michigan Library. 1937-03-03. Retrieved 2009-NOV-15.

((cite web)): Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ↑

Lincoln, Abraham (1858). "A House Divided Against Itself Cannot Stand". National Center for Public Policy Research. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

((cite web)): Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ "Abraham Lincoln". history.com.

- ↑ Boritt, Gabor S. (1997). Why the Civil War Came. Oxford University Press. pp. 3–30. ISBN 0195113764.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Blum, John M. (1981). Team of Rivals. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 340–342.

- ↑ Abe Lincoln's Hat Step into Reading Books Series A Step 2 Book by Martha Brenner Books at epinions.com

- ↑ "Captain Abraham Lincoln", Illinois State Military Museum, Illinois National Guard, accessed April 12, 2009.

- ↑ "Outline of U.S. History". United States Department of State. p. 73. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ "Last Public Address". Speeches and Writings. Abraham Lincoln Online. April 11, 1865. Retrieved 2008-09-15.

((cite web)): External link in|publisher= - ↑ Swanson, James. Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer. Harper Collins, 2006. pp. 42–3. ISBN 978-0-06-051849-3

- ↑ Steers, Edward. Blood on the Moon: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln. University Press of Kentucky, 2001. p. 123–24. ISBN 978-0-8131-9151-5

- ↑ "Abraham Lincoln". History. AETN UK. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ↑ Swanson, James (2006). Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer. Harper Collins. ISBN 9780060518493.

- ↑ "Ranking Our Presidents". James Lindgren. November 16, 2000. International World History Project.

- ↑ "Americans Say Reagan Is the Greatest President". Gallup Inc. February 28, 2011.

Other websites

- The Lincoln Institute

- Abraham Lincoln Research Site

- A One Page Summary of Abraham Lincoln's Life

- Abraham Lincoln at Find a Grave

- Lincoln's White House biography

- Abraham Lincoln -Citizendium

- Abe Lincoln History Site

| Vice President | Hannibal Hamlin (1861–1865) • Andrew Johnson (1865) | |

|---|---|---|

| Secretary of State | William H. Seward (1861–1865) | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Salmon P. Chase (1861–1864) • William P. Fessenden (1864–1865) • Hugh McCulloch (1865) | |

| Secretary of War | Simon Cameron (1861–1862) • Edwin M. Stanton (1862–1865) | |

| Attorney General | Edward Bates (1861–1864) • James Speed (1864–1865) | |

| Postmaster General | Montgomery Blair (1861–1864) • William Dennison (1864–1865) | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Gideon Welles (1861–1865) | |

| Secretary of the Interior | Caleb Blood Smith(1861–1862) • John Palmer Usher (1863–1865) | |

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||