A leaf is a green above-ground plant organ. Its main functions are photosynthesis and gas exchange. A leaf is flat so it absorbs the most light, and thin, so that the sunlight can get to the chloroplasts in the cells. Most leaves have stomata, which open and close. They regulate carbon dioxide, oxygen, and water vapour exchange with the atmosphere.

Plants with leaves all year round are evergreens, and those that shed their leaves are deciduous. Deciduous trees and shrubs generally lose their leaves in autumn. Before this happens, the leaves change colour. The leaves will grow back in spring. Leaves are normally green in color, which comes from chlorophyll found in the chloroplasts. Plants that lack chlorophyll cannot photosynthesize.

Leaves come in many shapes and sizes. The biggest undivided leaf is that of a giant edible arum. This lives in marshy parts of the tropical rain forest of Borneo. One of its leaves can be ten feet across and have a surface area of over 30 square feet (~2.8 sq. metres).[1]

However, leaves are always thin so carbon dioxide can diffuse quickly to all cells.

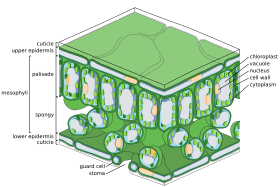

A leaf is a plant organ made up of tissues in a regular organisation. The major tissue systems present are:

The epidermis is the outer layer of cells covering the leaf. It forms the boundary separating the plant's inner cells from the external environment.

The epidermis is covered with pores called stomata. Each pore is surrounded on each side by chloroplast-containing guard cells, and two to four subsidiary cells. Opening and closing the stoma complex controls the exchange of gases and water vapor between the outside air and the interior of the leaf. This allows photosynthesis, without letting the leaf dry out.

Most of the interior of the leaf between the upper and lower layers of epidermis is a tissue called the mesophyll (Greek for "middle leaf"). This tissue is the main place photosynthesis takes place. The products of photosynthesis are sugars, which can be turned into other products in plant cells.

In ferns and most flowering plants, the mesophyll is divided into two layers:

Plants with leaves all year round are evergreens, and those that shed their leaves are deciduous. Deciduous trees and shrubs generally lose their leaves in autumn. Before this happens, the leaves change colour. The leaves grow back in Spring.

The 'veins' are a dense network of xylem, which supply water for photosynthesis, and phloem, which remove the sugars produced by photosynthesis. The pattern of the veins is called 'venation'.

In angiosperms the pattern of venation differs in the two main groups. Venation is usually is parallel in monocotyledons, but is an interconnecting network in broad-leaved plants (dicotyledons).

Many leaves are covered in trichomes (small hairs) which have a wide range of structures and functions. Some trichomes are prickles, some are scaled, some secrete substances such as oil. Carnivorous plants secrete digestive enzymes from trichomes.

The waxy cuticle is the waterproof, transparent outer surface of the leaf. It is waterproof to reduce water loss (transpiration) and transparent to allow light to enter the palisade cell.

What leaves look like on the plant varies greatly. Closely related plants have the same kind of leaves because they have all descended from a common ancestor. The terms for describing leaf shape and pattern is shown, in illustrated form, at Wikibooks.

Different terms are usually used to describe leaf placement (phyllotaxis):

Leaves form a helix pattern centered around the stem, with (depending upon the species) the same angle of divergence. There is a regularity in these angles and they follow the numbers in a Fibonacci sequence. This tends to give the best chance for the leaves to catch light.

Two basic forms of leaves can be described considering the way the blade (lamina) is divided.

Some leaves have a petiole (leaf stem). Sessile leaves do not: the blade attaches directly to the stem. Sometimes the leaf blade surrounds the stem, giving the impression that the shoot grows through the leaf.

In some Acacia species, such as the Koa Tree (Acacia koa), the petioles are expanded or broadened and function like leaf blades; these are called phyllodes. There may or may not be normal pinnate leaves at the tip of the phyllode.

A stipule, present on the leaves of many dicotyledons, is an appendage on each side at the base of the petiole resembling a small leaf. Stipules may be shed or not shed.

In the course of evolution, many species have leaves which are adapted to other functions.