| Dara Shukoh | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crown Prince of the Mughal Empire | |||||

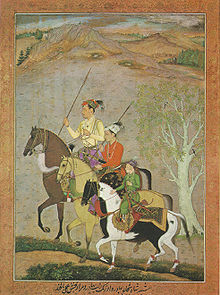

A Mughal miniature painting of Crown prince Dara Shikoh | |||||

| Born | 20 March 1615 Ajmer, Mughal Empire | ||||

| Died | 30 August 1659 (aged 44) Delhi, Mughal Empire | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | Nadira Banu Begum | ||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| House | Timurid | ||||

| Father | Shah Jahan | ||||

| Mother | Mumtaz Mahal | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

Dara Shukoh, also known as Dara Shikoh (20 March 1615 – 30 August 1659)[1] was the eldest son and heir-apparent of the fifth Mughal emperor Shah Jahan.[2] He was favoured as a successor by his father, Shah Jahan, and his older sister, Princess Jahanara Begum, but was defeated and later killed by his younger brother, Prince Muhiuddin (later, the Emperor Aurangzeb), in a bitter struggle for the imperial throne.

The course of the history of the Indian subcontinent, had Dara Shukoh prevailed over Aurangzeb, has been a matter of some conjecture among historians.[3][4][5]

Family

Dara Shukoh was born Taragarh fort Ajmer on 28 October 1615, the eldest son of Prince Shahab ud-din Muhammad Khurram (Shah Jahan) and his second wife, Mumtaz Mahal. Shukoh means grandeur, glory or splendour.[6][unreliable source?] When he was 12, his grandfather, Emperor Jahangir, died, and his father succeeded as emperor. Dara's siblings included his elder sister Jahanara Begum and their youngers siblings Shah Shuja, Roshanara Begum, Aurangzeb, Murad Bakhsh, and Gauhara Begum.[citation needed] Aurangzeb became the sixth Mughal Emperor.

Marriage

On 1 February 1633, Dara Shukoh married his first cousin, Nadira Banu, the daughter of his paternal uncle Sultan Parvez Mirza. By all accounts, it was an extremely happy and successful marriage. Both Dara Shukoh and Nadira were devoted to each other, so much so that Dara Shukoh never contracted any other marriage after marrying Nadira. The couple had eight children, of whom two sons and two daughters survived to adulthood.[citation needed]

Military service

As was common for all Mughal sons, Dara Shukoh was appointed as a military commander at an early age, receiving an appointment as commander of 12,000-foot and 6,000 horse in October 1633[7][unreliable source?] (roughly equivalent to a modern division commander or major general). He received successive promotions, being promoted to commander of 12,000-foot and 7,000 horse on 20 March 1636, to 15,000-foot and 9,000 horse on 24 August 1637, to 10,000 horse on 19 March 1638 (roughly equivalent to lieutenant general), to 20,000-foot and 10,000 horse on 24 January 1639, and to 15,000 horse on 21 January 1642.[7]

On 10 September 1642, Shah Jahan formally confirmed Dara Shukoh as his heir, granting him the title of Shahzada-e-Buland Iqbal ("Prince of High Fortune") and promoting him to command of 20,000-foot and 20,000 horse.[7] In 1645, he was appointed as subahdar (governor) of Allahabad. He was promoted to a command of 30,000-foot and 20,000 horse on 18 April 1648, and was appointed Governor of the province of Gujarat on 3 July.[citation needed]

As his father's health began to decline, Dara Shukoh received a series of increasingly prominent commands. He was appointed Governor of Multan and Kabul on 16 August 1652, and was raised to the title of Shah-e-Buland Iqbal ("King of High Fortune") on 15 February 1655.[7] He was promoted to command of 40,000-foot and 20,000 horse (roughly equivalent to general) on 21 January 1656, and to command of 50,000-foot and 40,000 horse on 16 September 1657.[citation needed]

The struggle for succession

On 6 September 1657, the illness of emperor Shah Jahan triggered a desperate struggle for power among the four Mughal princes, though realistically only Dara Shukoh and Aurangzeb had a chance of emerging victorious.[9] Shah Shuja was the first to make his move, declaring himself Mughal Emperor in Bengal and marched towards Agra from the east. Murad Baksh allied himself with Aurangzeb.

At the end of 1657, Dara Shukoh was appointed Governor of the province of Bihar and promoted to command of 60,000 infantry and 40,000 cavalry.[7]

Despite strong support from Shah Jahan, who had recovered enough from his illness to remain a strong factor in the struggle for supremacy, and the victory of his army led by his eldest son Sulaiman Shikoh over Shah Shuja in the battle of Bahadurpur on 14 February 1658, Dara Shukoh was defeated by Aurangzeb and Murad during the Battle of Samugarh, 13 km from Agra on 30 May 1658. Subsequently Aurangzeb took over Agra fort and deposed emperor Shah Jahan on 8 June 1658.[citation needed]

Death and aftermath

After the defeat, Dara Shukoh retreated from Agra to Delhi and thence to Lahore. His next destination was Multan and then to Thatta (Sindh). From Sindh, he crossed the Rann of Kachchh and reached Kathiawar, where he met Shah Nawaz Khan, the governor of the province of Gujarat who opened the treasury to Dara Shukoh and helped him to recruit a new army.[10] He occupied Surat and advanced towards Ajmer. Foiled in his hopes of persuading the fickle but powerful Rajput feudatory, Maharaja Jaswant Singh of Marwar, to support his cause, the luckless Dara Shukoh decided to make a stand and fight Aurangzeb's relentless pursuers but was once again comprehensively routed in the battle of Deorai (near Ajmer) on 11 March 1659. After this defeat he fled to Sindh and sought refuge under Malik Jiwan (Junaid Khan Barozai), an Afghan chieftain, whose life had on more than one occasion been saved by the Mughal prince from the wrath of Shah Jahan.[11][12] However, the treacherous Junaid betrayed Dara Shukoh and turned him (and his second son Sipihr Shukoh) over to Aurangzeb's army on 10 June 1659.[13]

Dara Shukoh was brought to Delhi, placed on a filthy elephant and paraded through the streets of the capital in chains.[14][15] Dara Shukoh's fate was decided by the political threat he posed as a prince popular with the common people – a convocation of nobles and clergy, called by Aurangzeb in response to the perceived danger of insurrection in Delhi, declared him a threat to the public peace and an apostate from Islam.He was assassinated by four of Aurangzeb's henchmen in front of his terrified son on the night of 30 August 1659 (9 September Gregorian). After death the remains of Dara Shukoh were buried in an unindentified grave in Humayan's tomb in Delhi.[16][17]

Niccolao Manucci, the Venetian traveler who worked in the Mughal court, has written down the details of Dara Shukoh's death. According to him, upon Dara's capture, Aurangzeb ordered his men to have his head brought up to him and he inspected it thoroughly to ensure that it was Dara indeed. He then further mutilated the head with his sword three times. After which, he ordered the head to be put in a box and presented to his ailing father, Shah Jahan, with clear instructions to be delivered only when the old King sat for his dinner in his prison. The guards were also instructed to inform Shah Jahan that, “King Aurangzeb, your son, sends this plate to let him (Shah Jahan) see that he does not forget him”. Shah Jahan instantly became happy (not knowing what was in store in the box) and uttered, “ Blessed be God that my son still remembers me”. Upon opening the box, Shah Jahan became horrified and fell unconscious.[18] Shah Jahan was deeply anguished, to the point where he began to pull out his beard and blood started coming out profusely.

Intellectual pursuits

Dara Shukoh is widely renowned[19] as an enlightened paragon of the harmonious coexistence of heterodox traditions on the Indian subcontinent. He was an erudite champion of mystical religious speculation and a poetic diviner of syncretic cultural interaction among people of all faiths. This made him a heretic in the eyes of his orthodox younger brother and a suspect eccentric in the view of many of the worldly power brokers swarming around the Mughal throne. Dara Shukoh was a follower of the Persian "perennialist" mystic Sarmad Kashani,[20] as well as Lahore's famous Qadiri Sufi saint Hazrat Mian Mir,[21] whom he was introduced to by Mullah Shah Badakhshi (Mian Mir's spiritual disciple and successor). Mian Mir was so widely respected among all communities that he was invited to lay the foundation stone of the Golden Temple in Amritsar by the Sikhs.

Dara Shukoh subsequently developed a friendship with the seventh Sikh Guru, Guru Har Rai. Dara Shukoh devoted much effort towards finding a common mystical language between Islam and Hinduism. Towards this goal he completed the translation of fifty Upanishads from their original Sanskrit into Persian in 1657 so that they could be studied by Muslim scholars.[22][23] His translation is often called Sirr-e-Akbar ("The Greatest Mystery"), where he states boldly, in the introduction, his speculative hypothesis that the work referred to in the Qur'an as the "Kitab al-maknun" or the hidden book, is none other than the Upanishads.[24] His most famous work, Majma-ul-Bahrain ("The Confluence of the Two Seas"), was also devoted to a revelation of the mystical and pluralistic affinities between Sufic and Vedantic speculation.[25] The book was authored as a short treatise in Persian in 1654-55.[26]

The library established by Dara Shukoh still exists on the grounds of Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University, Kashmiri Gate, Delhi, and is now run as a museum by Archaeological Survey of India after being renovated.[27][28]

Patron of art

He was also a patron of fine arts, music and dancing, a trait frowned upon by his younger sibling Muhiuddin, later the Emperor Aurangzeb. The 'Dara Shikoh' is a collection of paintings and calligraphy assembled from the 1630s until his death. It was presented to his wife Nadira Banu in 1641–42[29] and remained with her until her death after which the album was taken into the royal library and the inscriptions connecting it with Dara Shukoh were deliberately erased; however not everything was vandalised and many calligraphy scripts and paintings still bear his mark.

Dara Shukoh is also credited with the commissioning of several exquisite, still extant, examples of Mughal architecture – among them the tomb of his wife Nadira Banu in Lahore,[30] the tomb of Hazrat Mian Mir also in Lahore,[31] the Dara Shikoh Library in Delhi,[32] the Akhun Mullah Shah Mosque in Srinagar in Kashmir[33] and the Pari Mahal garden palace (also in Srinagar in Kashmir).[34]

In popular culture

- The issues surrounding Dara Shukoh's impeachment and execution are used to explore interpretations of Islam in a 2008 play, The Trial of Dara Shikoh,[35] written by Akbar S. Ahmed.[36]

- He is also the subject of a 2010 play called Dara Shikoh, written and directed by Shahid Nadeem of the Ajoka Theatre Group in Pakistan.[37]

- Shukoh is the subject of the 2007 play Dara Shikoh, written by Danish Iqbal and staged by, among others, the director M S Sathyu in 2008.[38]

- He is also a character played by Vaquar Sheikh in the 2005 Bollywood film Taj Mahal: An Eternal Love Story, directed by Akbar Khan.

- Dara Shukoh is the name of the protagonist of Mohsin Hamid's 2000 novel Moth Smoke, which reimagines the story of his trial unfolding in contemporary Pakistan.[39]

- The television series Upanishad Ganga had two episodes titled "Veda - The Source of Dharma 1" and "Veda - The Source of Dharma 2", featuring Dara Shukoh played by actor Zakir Hussain.[40]

- Gopalkrishna Gandhi wrote a play in verse titled Dara Shukoh on his life.[41]

- Bengali Writer Shyamal Gangopadhyay also wrote a novel on his life Shahjada Dara Shikoh.[citation needed]

- Assamese writer and politician, Omeo Kumar Das wrote a book called Dara Shikoh: Jeevan O Sadhana.

- An Assamese novel, Kalantarat Shahzada Dara Shikoh, was written by author Nagen Goswami.[citation needed]

- "Dara Shikoh" - a poem by poet Abhay K published in 2014 lamented the fact that there were no streets named after Dara.[42]

- New Delhi Municipal Corporation (NDMC) changed Dalhousie Road's name to Dara Shikoh Road on February 6, 2017.[43]

- In 2016 Bharatvarsh TV series, Rohit Purohit played the role of Dara Shukoh.

- In The 2017 novel 1636: Mission to the Mughals he is one of the central characters.

Full title

Padshahzada-i-Buzurg Martaba, Jalal ul-Kadir, Sultan Muhammad Dara Shikoh, Shah-i-Buland Iqbal[7]

Governorship

- Lahore 1635 - 1636

- Allahabad 1645 - 1647

- Malwa 1642 - 1658

- Gujrat 1648

- Multan Kabul 1652 - 1656

- Bihar 1657 - 1659

Works

- Writings on Sufism and the lives of awliya (Muslim saints):

- Safinat ul- Awliya

- Sakinat ul-Awliya

- Risaala-i Haq Numa

- Tariqat ul-Haqiqat

- Hasanaat ul-'Aarifin

- Iksir-i 'Azam (Diwan-e-Dara Shikoh)

- Writings of a philosophical and metaphysical nature:

- Majma-ul-Bahrain (The Mingling of Two Oceans)[44]

- So’aal o Jawaab bain-e-Laal Daas wa Dara Shikoh (also called Mukaalama-i Baba Laal Daas wa Dara Shikoh)

- Sirr-e-Akbar (The Great Secret, his translation of the Upanishads in Persian)[45]

- Persian translations of the Yoga Vasishta and Bhagavad Gita.

See also

References

- ^ chief, Stanley Wolpert, ed. in (2006). Encyclopedia of India. Detroit [u.a.]: Scribner's, Thomson Gale. p. 306. ISBN 9780684313511.

((cite book)): CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thackeray, Frank W.; editors, John E. Findling, (2012). Events that formed the modern world : from the European Renaissance through the War on Terror. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 240. ISBN 9781598849011.

((cite book)):|last2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "India was at a crossroads in the mid-seventeenth century; it had the potential of moving forward with Dara Shikoh, or of turning back to medievalism with Aurangzeb." Eraly, Abraham (2004). The Mughal Throne : The Saga of India's Great Emperors. London: Phoenix. p. 336. ISBN 0-7538-1758-6.

"Poor Dara Shikoh!....thy generous heart and enlightened mind had reigned over this vast empire, and made it, perchance, the garden it deserves to be made". William Sleeman (1844), E-text of Rambles and Recollections of an Indian Official p.272 - ^ Dara Shikoh Britannica.com.

- ^ Dara Shikoh Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, by Josef W. Meri, Jere L Bacharach. Routledge, 2005. ISBN 0-415-96690-6. Page 195-196.

- ^ "Who is Dara Shukoh?".

- ^ a b c d e f "delhi6". royalark.net.

- ^ unknown (17th century). "Dara Shikuh with his army". 17th Century Mughals & Marathas. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

((cite web)): Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sarkar, Jadunath (1984). A History of Jaipur. New Delhi: Orient Longman. pp. 113–122. ISBN 81-250-0333-9.

- ^ Eraly, The Mighal Throne : The Saga of India's Great Emperors, cited above, page 364.

- ^ Junaid Khan Barozai also known as Malik Jiwan tittle Bakhtiyar Khan

- ^ Francois Bernier Travels in the Mogul Empire, AD 1656–1668.

- ^ Junaid Khan Barozai received the tittle of Nawab Bakhtiyar Khan for this act of treachery

- ^ "Bad Muslim, good Muslim: Out with Aurangzeb, in with Dara Shikoh".

- ^ "The captive heir to the richest throne in the world, the favourite and pampered son of the most magnificent of the Great Mughals, was now clad in a travel-tainted dress of the coarsest cloth, with a dark dingy-coloured turban, such as only the poorest wear, on his head, and no necklace or jewel adorning his person." Sarkar, Jadunath (1962). A Short History of Aurangzib, 1618–1707. Calcutta: M. C. Sarkar and Sons. p. 78.

- ^ Hansen, Waldemar (1986). The Peacock Throne : The Drama of Mogul India. New Delhi: Orient Book Distributors. pp. 375–377. ISBN 978-81-208-0225-4.

- ^ https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.61973/2015.61973.Maasir-i--Alamgiri-1947_djvu.txt

- ^ Manucci, Niccolao (1989). Mogul India Or Storia Do Mogor 4 Vols. Set. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors (P) Limited. pp. 340–41. ISBN 817156058X.

- ^ The Hindu see for example this article in The Hindu.

- ^ Katz, N. (2000) 'The Identity of a Mystic: The Case of Sa'id Sarmad, a Jewish-Yogi-Sufi Courtier of the Mughals in: Numen 47: 142–160.

- ^ Dara Shikoh The empire of the great Mughals: history, art and culture, by Annemarie Schimmel, Corinne Attwood, Burzine K. Waghmar. Translated by Corinne Attwood. Published by Reaktion Books, 2004. ISBN 1-86189-185-7. Page 135.

- ^ "Lahore's iconic mosque stood witness to two historic moments where tolerance gave way to brutality".

- ^ Dr. Amartya Sen notes in his book The Argumentative Indian that it was Dara Shikoh's translation of the Upanishads that attracted William Jones, a Western scholar of Indian literature, to the Upanishads, having read them for the first time in a Persian translation by Dara Shikoh.Sen, Amartya. The Argumentative Indian.

- ^ Gyani Brahma Singh 'Brahma', Dara Shikoh – The Prince who turned Sufi in The Sikh Review[permanent dead link]"the reference in Al Qur’an to the hidden books – ummaukund-Kitab – was to the Upanishads, because they contain the essence of unity and they are the secrets which had to be kept hidden, the most ancient books."

- ^ "Prince of peace".

- ^ "Emperor's old clothes".

- ^ Dara Shikoh's Library, Delhi Archived 11 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine Govt. of Delhi.

- ^ Battling time, Dara Shikoh’s Library cries out for help

- ^ Dara Shikoh album British Library.

- ^ Nadira Banu's tomb A view of Nadira Banu's tomb

- ^ Mazar Hazrat Mian Mir Archived 2 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine entertaining description of the monument and its history

- ^ Dara Shikoh Library Archived 21 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine description of Dara Shikoh library

- ^ "Google Image Result for http://www.koausa.org/Monuments/PlateXII.jpg". google.co.uk.

((cite web)): External link in|title= - ^ "Google Image Result for http://lh4.ggpht.com/_w4GEiBHJ-rc/R_oNe0nuZNI/AAAAAAAAQWI/P08iBhPrYts/Pari+Mahal.jpg". google.co.uk.

((cite web)): External link in|title= - ^ ‘The Trial of Dara Shikoh’ – A Play in Three Acts Text of the play with an Introduction by the author.

- ^ Published as Akbar Ahmed: Two Plays. London: Saqi Books, 2009. ISBN 978-0-86356-435-2, ‘The Trial of Dara Shikoh’ – A Thought-Provoking Play Archived 15 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine A review of the play.

- ^ Ajoka’s Dara – an ancient story of modern day proportions Archived 14 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Daily Times (Pakistan), 19 April 2010

- ^ "For king and country". The Hindu.

- ^ Hamid, Mohsin. (2000). Moth Smoke. p. 247.

- ^ "Episode-guide". www.upanishadganga.com. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Dara Shukoh". Goodreads. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ Dara Shikoh and other poems The Caravan, May 1, 2014

- ^ http://indianexpress.com/article/research/dalhousie-road-renamed-after-dara-shikoh-why-hindutva-right-wingers-favour-a-mughal-prince/

- ^ MAJMA' UL BAHARAIN or The Mingling Of Two Oceans, by Prince Muhammad Dara Shikoh, Edited in the Original Persian with English Translation, notes & variants by M.Mahfuz-ul-Haq, published by The Asiatic Society, Kolkata, Bibliotheca Indica Series no. 246, 1st. published 1929. See also this Archived 9 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine book review by Yoginder Sikand, indianmuslims.in.

- ^ See the section on his Intellectual Pursuits.

Bibliography

- Eraly, Abraham (2004). The Mughal Throne: The Saga of India's Great Emperors. Phoenix, London. ISBN 0753817586.

- Hansen, Waldemar [1986]. The Peacock Throne: The Drama of Mogul India. Orient Book Distributors, New Delhi.

- Mahajan, V.D. (1978). History of Medieval India. S. Chand.

- Sarkar, Jadunath (1984). A History of Jaipur. Orient Longman, New Delhi.

- Sarkar, Jadunath (1962). A Short History of Aurangzib, 1618–1707. M. C. Sarkar and Sons, Calcutta.

External links

- Bernier, Francois Travels in the Mogul Empire, AD 1656–1668

- Gyani Brahma Singh, Dara Shikoh – The Prince who turned Sufi[permanent dead link] in The Sikh Review

- Manucci, Niccolo Storia de Mogor or Mogul Stories''

- Sleeman, William (1844), E-text of Rambles and Recollections of an Indian Official

- Srikand, Yoginder Dara Shikoh's Quest for Spiritual Unity

- Dara Shikoh Library

- The Dara Shikoh Album British Museum Online Gallery

- Majmaul Bahrain by Dara Shikoh English translation with original Persian text [1]

| Emperors | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administration |

| ||||||||

| Conflicts |

| ||||||||

| Architecture |

| ||||||||

| See also | |||||||||

| Successor states | |||||||||

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Academics | |

| Artists | |

| People | |

| Other | |