| Siege of Trichinopoly (1743) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

2,000 Sowars 4,000 Sepoy |

80,000 Sowars 200,000 Sepoy | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown | unknown | ||||||

The Siege of Trichinopoly (March 1743 – August 1743) took place at Trichinopoly during an extended series of conflicts between the Nizam of Hyderabad and the Maratha Empire for control over the Carnatic region of the Deccan Plateau. In Deccan, the Mughal Empire controlled six governorates (Subah): Khandesh, Bijapur, Malwa, Aurangabad, Hyderabad and Carnatic. In 1714 Nizam I was appointed as Viceroy of Deccan. In the process to obtain a complete suzerainty of Deccan, the Nizam surrounded the town of Trichinopoly, which was governed by Maratha commander Murari Rao under the control of Shahu I. On 29 August 1743, Murari Rao surrendered and Trichinopoly came under the suzerainty of Nizam I after a six month siege. The Nizam regained control of Deccan upon defeating the Maratha empire and its suzerainty in the Carnatic region.

By the end of 1743, the Nizam regained full control of Deccan. This stopped the Marathas interference into the region, which had overthrown the internal rebellion of regional governors (Subedar) and monitored the activities of British East India company and French East India Company by limiting their access onto ports and trading.

In 1748 when the Nizam died, Deccan became the center of a power struggle that led to a series of complicated wars of succession (1748–1762) among his sons and grandson Nasir Jung, Salabat Jung, Nizam Ali khan and Muzaffar Jung. The three Carnatic Wars (1746–1763) took place for the title of the Nawab of Arcot: Chanda Saheb vs. Muhammed Ali Khan Wallajah, and the legitimate ruler of Mysore Krishnaraja vs. Hyder Ali. Each of whom were supported by either Robert Clive or Frenchman Joseph François Dupleix, even though they were rivals who increased their interference and influence among their oppenents and local rulers.

History

In 1714, Mughal emperor Farrukhsiyar appointed Mir Qamar-ud-din Khan (Nizam I) to be Viceroy of the Deccan, which consists of six Mughal governorates (Subah): Khandesh, Bijapur, Malwa, Aurangabad, Hyderabad and Carnatic. In 1721, he was commissioned to Delhi and became Prime Minister of the Mughal empire. His differences with the court nobles caused him to resigned from all the imperial responsibilities in 1723 and leave for Deccan.[1]: 143 [2]: 100:105 [3]: 95

On 11 October 1724, the Nizam defeated Mubariz Khan, who was the Mughal governor of Hyderabad and an imperial officer, to establish autonomy of the Deccan region. The region was named as Hyderabad Deccan, and began what is known as the Asaf Jahi dynasty. He retained the title as Nizam ul-Mulk, and was referred to as "Asaf Jahi Nizams", or more commonly, the Nizam of Hyderabad.[4]: 241:260 [5] He acquired de facto control over Deccan, and thus all six Mughal governorates became his feudatory.[6]: 98 [7]: 298:310

Background

In the 1720s, the Carnatic region of southern India was an autonomous dominion of Mughal empire under the suzerainty of Asaf Jah I, the Nizam of Hyderabad. In 1710, the Nizam appointed Muhammed Saadatullah Khan as Nawab of the Carnatic. Saadatullah died in 1732, and would be succeeded by his nephew Dost Ali Khan.[6]: 97:98

Tukkoji Bhonsle, a Maratha ruler of Trichinopoly, died in 1736. He left his son Ekoji II to succeed him and his wife Rani Minakshi, who was acting as a regent for her young son. Dost Ali sent Chanda Sahib, his son-in-law and diwan, to the province, claiming they owed tribute payments (chauth). He inveigled into the court of Rani Minakshi and abused her trust to the fortress. He threw her into prison where she died of grief. In 1739, Dost Ali rewarded Chanda Sahib with the title Nawab of Trichinopoly. This decisive act and the refusal of tributary payment by Dost Ali Khan enraged the Marathas. They used the absence of the Nizam in Deccan due to his engagement in resolving disputes in the North India. In 1740, Raghoji I Bhonsle comanded the Maratha army of 50,000 soliders to invade the Carnatic region; in a battle at Damalcherry, a pass near Arcot, Dost Ali Khan was killed. His son and successor Safdar Ali Khan negotiated and agreed a tribute payment to the Marathas. Confident of his defense, Chanda Saheb refused to negotiate with Raghoji I Bhonsle, pay tribute and surrender Trichinopoly. In Raghoji I Bhonsle's siege of Trichinopoly, Chanda Saheb initially resisted the siege. The Marathas bribed an officer who betrayed Chanda Saheb and left a free opening to the Maratha army through a very important mountain post. The Marathas occupied Trichinopoly and took Chanda Sahab as a prisoner to Satara. Murari Rao was installed as Maratha's governor of Trichinopoly in 1741.[6]: 98:100 [8]: 150:151 [9]: 276:278 [10]: 41:42

In 1741, the Nizam just returned from Delhi after resolving a settlement between Muhammad Shah and Nadir Shah, who had invaded Delhi. Nizam demanded Safdar Ali, who had been recognized as the Nawab of Carnatic, to settle the debts of Subah Deccan. Safdar Ali, who recently negotiated Marathas to an agreement of the indemnity and tributary payments, was hardly in a position to meet the demands of the Nizam and the Maraths. To encounter this double payments, he imposed additional levy from his region town administrators. Safdar Ali’s brother-in-law, Nawab Muruza Ali Khan, an administrator of Vellore, refused to pay increased levies and prepared a plot with his wife, who was also sister of Safdar Ali, and coped to murder Safdar Ali, he declared himself as the Nawab of the Carnatic. The declaration irritated other nobles and brought Nawab Saeed Muhammad Khan, who was in Madras, son of Safdar Ali, to be recognized as the Nawab of the Carnatic.[11]: 2:5

Siege

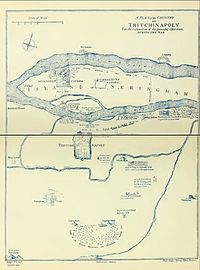

In 1742, the Nizam, who was busy in the affairs at Delhi, just returned to the Deccan. After the invasion of Nadir Shah in Delhi the Mughals were in no position to stop the Marathas in the Carnatic region. The Nizam was enraged to see the rebellion of Nawab of Arcot and the Maratha occupation of the Carnatic region; particularly, Trichinopoly. While he was contemplating an invasion of Carnatic region to reestablish his authority as Viceroy of Deccan, Dalavayi Devarajaiya of Mysore when came to know he joined the Nizam to take back Trichinopoly from the Maratha's, for which in January 1743 he made and agreement with the Nizam to pay 10,000,000 ₹s if the latter would bring Trichinopoly under Mysore. In February 1743, the Nizam marched towards Carnatic region from Hyderabad.[12]: 74:75 [13]: 81 [14]

After deposing Muhammed Saadatullah Khan II in Arcot, the Nizam marched towards Trichinopoly. In March 1743, he reached Trichinopoly with an army of 200,000 sepoy, 80,000 Sowar and some 150 War elephant. Maratha's governor Murari Rao Ghorpade, who held Trichinopoly from July 1741, could not show much resistance, but refused to surrender. As a result, the Nizam laid siege to Trichinopoly, blocking and disconnecting the supply line of Maratha's aid. Murari Rao could not hold for long; his army stationed in Trichinopoly for the defense of fort was less than the Nizam's (4000 Sepoy and 2000 Sowars).[15] When compared to the opponents, he could not expect any help from his Maratha superiors as they were indulged in internal conflicts between the Maratha ruler Raghoji I Bhonsle and Peshwa Balaji Baji Rao. Murari Rao surrendered to the Nizam and came to terms of an agreement where the Nizam offered him governance of the hill-fort of Penukonda around the fort and 200,000 ₹s in cash. The six month siege ended on 29 August 1743. The surrender of Trichinopoly brought an end to the Maratha suzerainty of the Carnatic region, which they lost direct rule of; the Nizam regains the authority over the Deccan region.[12]: 74:75 [13]: 81 [16]: 69:73 [17]: 1034

As per the agreement of Trichinopoly, if Dalavayi wants control of Trichinopoly, he needs to pay 10,000,000 ₹s to the Nizam. The Dalavoy could not pay the sum as he was suffering with the financial crisis after paying heavy tributary taxes, which includes 50,000,000 ₹s, to Maratha ruler Raghuji in 1740–1741 after Maratha invasion of carnatic region. In October 1743, the Nizam left for Golconda and appointed Nawab Anwaruddin Khan of Arcot to be in charge of Trichinopoly.[18]: 267

Aftermath

When Nizam took full control of Trichinopoly in September 1743.[16]: 43:79 [19]: 52:53 Nizam appointed Khwaja Abdullah as the ruler and returned to Golkonda.[2]: 103 When the Nawab of the Carnatic Muhammed Ali Khan Wallajah was dethroned by Chanda Sahib after the Battle of Ambur in 1749, the former took refuge in Tiruchirappalli, where he set up his base.[20]: 126:127 [21]: 222 [16]: 115 The subsequent siege of Trichinopoly (1751–1752) by Chanda Sahib took place during the Second Carnatic War between the British East India Company and Muhammed Ali Khan Wallajah on one side and Chanda Sahib and the French East India Company on the other.[16]: 148 The British were victorious and Wallajah was restored to the throne as Nawab of Arcot. During his reign he proposed renaming the city Natharnagar after the Sufi saint Nathar Vali, who is thought to have lived there in the 12th century AD.[22]: 233 [23]: 137

From 1744-46 two expenditure were sent by Shahu I to expand the Maratha supremacy over the Carnatic affairs; first being lead by Babuji Naik of Baramati and was defeated after he confronted by Anwaruddin Khan of Arcot and Muzaffar Jung assigned by the Nizam. Second expedition was in 1746 and to be leaded by Babuji Naik and Fateh Singh Bhonsle of Akkalkot who were again unsuccessful to take back Trichinopoly and were defeated by the Nizam's army.[1]: 143 [2]: 100:105 [24]: 30:35 [9] Three years after the siege, in 1746, Marathas under Peshwa Balaji Bajirao sent a military expedition to Carnatic, led by Sadashivrao Bhau. The Maratha army overran the region and brought it under their control. Nizam's army, under Nasir Jung tried to obstruct the Marathas, but was defeated and repulsed by Sadashivrao Bhau. Maratha influence in the region was replaced by the French and British forces.[1]: 143 [2]: 100:105

By 1745, Nizam-ul-Mulk established Hyderabad as an independent kingdom. The coastal Carnatic region was a dependency of Hyderabad, a power struggle ensued after his death between his son, Nasir Jung, and his grandson, Muzaffar Jung, which was the opportunity France and England needed to interfere in Indian politics. France aided Muzaffar Jung while England aided Nasir Jung. Several erstwhile Mughal territories were autonomous such as the Carnatic, ruled by Nawab appointed under the suzerainty of Nizam, despite being under the legal purview of the Nizam of Hyderabad. French and English interference included those of the affairs of the Nawab which instigated and lead to the Three Carnatic Wars that were a series of wars fought between 1746 and 1763 among the Maratha-(two Peshwas with differences Raghoji I Bhonsale and Balaji Bajirao), the Nizam of Hyderabad-(two contenders Nasir Jung and Muzaffar Jung), the Nawab of Arcot-(two contenders Chanda Saheb and Muhammed Ali Khan Wallajah), British-(Robert Clive) and French-(Joseph François Dupleix). They all keep changing support system between one another during and after war.[8]: 150:159

See also

References

- ^ a b c Mehta, Jaswant Lal (2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India: 1707–1813. Sterling Publishing. ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6.

- ^ a b c d Chhabra, G.S. (2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India: 1707–1813. Vol. I. Lotus Press. ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Roy, Olivier (2011). Holy Ignorance: When Religion and Culture Part Ways. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-80042-6.

- ^ Richards, J. F. (1975). "The Hyderabad Karnatik, 1687–1707". Modern Asian Studies. 9 (2): 241–260. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00004996.

- ^ Ikram, S. M. (1964). "A century of political decline: 1707–1803". In Embree, Ainslie T (ed.). Muslim civilization in India. Columbia University. ISBN 978-0-231-02580-5.

((cite book)):|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)- Rao, Sushil (11 December 2009). "Testing time again for the pearl of Deccan". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ^ a b c Mackenna, P. J.; Taylor, William Cooke (2008). Ancient and Modern India. Wertheimer and Company. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Corner(Julia), Miss (1847). The History of China & India: Pictorial and Descriptive (PDF). H. Washbourne. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ a b Naravane, M.S. (2014). Battles of the Honorourable East India Company. A.P.H. Publishing Corporation. ISBN 9788131300343.

- ^ a b Chandramauliswar, R. (1953). "Maratha invasion of the Madura country (1740-1745)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 16. Jstor: 276–278. JSTOR 44303889.

- ^ Brackenbury, C.F (2000). District Gazetteer, Cuddapah. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120614826. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Nizam-British Relations, 1724–1857 at Google Books

- ^ a b Illustrated Guide to the South Indian Railway. Asian Educational Services. 1926. ISBN 9788120618893. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ a b Black, Jeremy (2012). War in the Eighteenth-Century World. Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 9788120618893. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Rajayyan, K. "THE MARATHAS AT TRICHINOPOLY : 1741-1743." Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute 51, no. 1/4 (1970): 222-30. Accessed August 14, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/41688690.

- ^ Chand, S (2009). The Cambridge History of India. Vol. 4. The University of Michigan. p. 384. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d Ramaswami, N.S (1984). Political History of Carnatic Under the Nawabs. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 9780836412628. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313335396. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ Raj, Raghavendra (2004). "4". Early wodeyars of Mysore and Tamil nadu a study in political economic and cultural relations (Dalvoys relations with Tamil Nadu (1704-1761)). University of Mysore (Department of History). Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Subramanian, K. R. (1928). The Maratha Rajas of Tanjore. Madras: K. R. Subramanian.

- ^ Rose, John Holland; Newton, Arthur Percival (1929). The Cambridge History of the British Empire. CUP Archive. GGKEY:55QQ9L73P70. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Markovits, Claude (2004). A History of Modern India, 1480–1950. Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1-84331-152-2.

((cite book)): Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Bayly, Susan (2004). Saints, Goddesses and Kings: Muslims and Christians in South Indian Society, 1700–1900. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89103-5. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Muthiah, S. (2008). Madras, Chennai: A 400-year Record of the First City of Modern India. Palaniappa Brothers. ISBN 978-81-8379-468-8. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Chitnis, Krishnaji Nageshrao (2000). The Nawabs of Savanur. Atlantic Publishers. ISBN 9788171565214. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

| Emperors | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administration |

| ||||||||

| Conflicts |

| ||||||||

| Architecture |

| ||||||||

| See also | |||||||||

| Successor states | |||||||||

| Chhatrapatis | |

|---|---|

| Peshwas | |

| Amatya & Pratinidhi | |

| Women | |

| Maratha Confederacy | |

| Battles |

|

| Wars | |

| Adversaries | |

| Forts | |

| Coins | |

| Asaf Jahi dynasty | |

|---|---|

| Prime ministers of Hyderabad State | |

| Hospitals established | |

| Educational institutions established | |

| Nizams Dominion | |

| Donations to temples, educational institutions | |

| Nizam | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dewan |

| |

| Women | ||

| Currency | ||