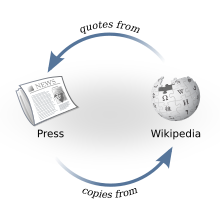

In 2011, Randall Munroe in his comic xkcd coined the term "citogenesis" to describe the creation of "reliable" sources through circular reporting.[1][2] This is a list of some well-documented cases where Wikipedia has been the source.

Known citogenesis incidents[edit]

- Did Sir Malcolm Thornhill make the first cardboard box? A one-day editor said so in 2007 in this edit. Though it was removed a year later, it kept coming back, from editors who also invested a lot in vandalizing the user page of the editor who removed it. Thornhill propagated to at least two books by 2009, and appears on hundreds of web pages. A one-edit editor cited one of the books in the article in 2016.[3]

- Ronnie Hazlehurst: A Wikipedia editor added a sentence to Hazlehurst's biography claiming he had written the song "Reach", which S Club 7 made into a hit single. The information was reproduced in multiple obituaries and reinserted in Wikipedia citing one of these obituaries.[4]

- Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg: A Wikipedia editor added "Wilhelm" as an 11th name to his full name. Journalists picked it up, and then the "reliable sources" from the journalists were used to argue for its inclusion in the article.[5][6]

- Diffs from German Wikipedia: :de:Diskussion:Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg/Archiv/001 § Diskussionen zum korrekten vollständigen Namen

- Sacha Baron Cohen: Wikipedia editors added fake information that comedian Sacha Baron Cohen worked at the investment banking firm Goldman Sachs, a claim which news sources picked up and was then later added back into the article citing those sources.[7]

- Korma: A student added 'Azid' to Korma as an alternative name as a joke. It began to appear across the internet, which was eventually used as justification for keeping it as an alternative name.[8]

- Is the radio broadcast where Emperor Hirohito announced Japan's WWII surrender referred to as the "Jewel Voice Broadcast" in English? Google Books search results and the Google Books Ngram Viewer reveal that this moniker appears to have been non-existent until a user added this literal translation of the Japanese name to the Wikipedia article in 2006[9] (and another user moved the article itself to that title in 2016[10]). Since then, the usage of this phrase has skyrocketed[11] and when it was suggested in 2020 that the article should be moved because this "literal translation" is actually incorrect—a better translation of the original Japanese would have been "the emperor's voice broadcast"—it was voted down based on it appearing in plenty of recent reliable sources.[12]

- Roger Moore: A student added 'The College of the Venerable Bede' to the early life of Roger Moore, repeatedly editing the page to cause citogenesis. This has been ongoing since April 2007 and was so widely believed that reporters kept asking him about it in interviews.[13]

- Maurice Jarre: When Maurice Jarre died in 2009, a student inserted fake quotes in his Wikipedia biography that multiple obituary writers in the mainstream press picked up. The student "said his purpose was to show that journalists use Wikipedia as a primary source and to demonstrate the power the internet has over newspaper reporting." The fakes only came to light when the student emailed the publishers, causing widespread coverage.[14]

- Invention of QALYs, the quality-adjusted life year. An article published in the Serbian medical journal Acta facultatis medicae Naissensis stated that "QALY was designed by two experts in the area of health economics in 1956: Christopher Cundell and Carlos McCartney".[15] These individuals—along with a third inventor, "Toni Morgan" (an anagram of 'Giant Moron')—were listed on Wikipedia long before the publication of the journal article which was subsequently used as a citation for this claim.[16]

- Invention of the butterfly swimming stroke: credited to a "Jack Stephens" in The Guardian (archive), based on an undiscovered joke edit.[17][18]

- Glucojasinogen: invented medical term that made its way into several academic papers.[19]

- Founder of The Independent: the name of a student, which was added as a joke, found its way into the Leveson Inquiry report as being a co-founder of The Independent newspaper.[20][21]

- Jar'Edo Wens: fictitious Australian Aboriginal deity (presumably named after a "Jared Owens") that had an almost ten-year tenure in Wikipedia and acquired mentions in (un)learned books.[22][18]

- Inventor of the hair straightener: credited to Erica Feldman or Ian Gutgold on multiple websites and, for a time, a book, based on vandalism edits to Wikipedia.[23][24][8]

- Boston College point shaving scandal: For more than six years, Wikipedia named an innocent man, Joe Streater, as a key culprit in the 1978–79 Boston College basketball point shaving scandal. When Ben Koo first investigated the case, he was puzzled by how many retrospective press and web sources mentioned Streater's involvement in the scandal, even though Streater took part in only 11 games in the 1977–78 season, and after that never played for the team again. Koo finally realised that the only reason that Streater was mentioned in Wikipedia and in every other article he had read was because it was in Wikipedia.[25]

- The Chaneyverse: Series of hoaxes relying in part on circular referencing. Discovered in December 2015 and documented at User:ReaderofthePack/Warren Chaney.[26]

- Dave Gorman hitch-hiking around the Pacific Rim: Gorman described on his show Modern Life is Goodish (first broadcast 22 November 2016) that his Wikipedia article falsely described him as having taken a career break for a sponsored hitch-hike around the Pacific Rim countries, and that after it was deleted, it was reposted with a citation to The Northern Echo newspaper which had published the claim.[27]

- The Dutch proverb "de hond de jas voorhouden" ("hold the coat up to the dog") did not exist before January 2007[28] as the author confessed on national television.[29]

- 85% of people attempting a water speed record have died in the attempt: In 2005, an unsourced claim in the Water speed record article noted that 50% of aspiring record holders died trying. In 2008, this was upped, again unsourced, to 85%. The claim was later sourced to sub-standard references and removed in 2018 but not before being cited in The Grand Tour episode "Breaking, Badly."

- Mike Pompeo served in the Gulf War: In December 2016, an anonymous user edited the Mike Pompeo article to include the claim that Pompeo served in the Gulf War. Various news outlets and senator Marco Rubio picked up on this claim, but the CIA refuted it in April 2018.[30][18]

- The Casio F-91W digital watch was long listed as having been introduced in 1991, whereas the correct date was June 1989. The error was introduced in March 2009 and repeated in sources such as the BBC, The Guardian, and Bloomberg, before finally being corrected in June 2019 thanks to vintage watch enthusiasts.[31]

- The Urker vistaart (fish pie from Urk) was in the article namespace on Dutch Wikipedia from 2009 to 2017. There were some doubts about the authenticity in 2009, but no action was taken. After someone mentioned in 2012 that Topchef, a Dutch show on national television featured the Urker vistaart, the article was left alone until 2017 when Munchies, Vice Media-owned food website published the confession of the original authors.[32] The article was subsequently moved to the Wikipedia: namespace.

- Karl-Marx-Allee: In February 2009, an anonymous editor on the German Wikipedia introduced a passage that said Karl-Marx-Allee (a major boulevard lined with tiled buildings) was known as "Stalin's bathroom". The nickname was repeated in several publications, and later, when the anonymous editor that added it as a joke tried to retract it, other editors restored it due to "reliable" citations. A journalist later revealed that he was the anonymous editor in an article taking credit for it.[18]

- In May 2008, the English Wikipedia article Mottainai was edited to include a claim that the word mottainai appeared in the classical Japanese work Genpei Jōsuiki in a portion of the text where the word would have had its modern meaning of "wasteful". (The word actually does appear at two completely different points in the text, with different meanings, and the word used in the passage in question is actually a different word.) Later (around October 2015), at least one third-party source picked up this claim. The information was challenged in 2018 (talk page consensus was to remove it in February, but the actual removal took place in April), and re-added with the circular citation in November 2019.

- In June 2006, the English Wikipedia article Eleagnus was edited to include an unreferenced statement "Goumi is among the "nutraceutical" plants that Chinese use both for food and medicine." An immediate subsequent edit replaced the word "Goumi" in the statement with "E. multiflora". An equivalent statement was included in the article Elaeagnus multiflora when it was created in August 2006. The version of the statement in the article Eleagnus was later included in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs, a collation of Wikipedia articles MobileReference published in January 2008. In May 2013, after the statement in the article Elaeagnus multiflora had been removed for the lack of a long-requested citation, it was immediately reinstated with a citation to MobileReference's The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs.

- Entertainer Poppy posted a tweet in 2020 that showed only ring, party and bride emojis. Someone later edited her article by suffixing the last name of her at-the-time boyfriend, Ghostemane, to hers assuming she was married; it was reverted citing the vagueness of her tweet. The suffix was later restored, now citing an article from Access Hollywood which at the time said that was her legal name, though it has since been corrected.[33][34][35][36]

- In 2009, the English Amelia Bedelia Wikipedia article was edited to falsely claim the character was based on a maid in Cameroon. This claim had subsequently been repeated among different sources, including the current author of the books, Herman Parish. In July 2014, the claim was removed from Wikipedia after the original author of the hoax wrote an article debunking it.[37][38]

- Origin of band Vulfpeck: Jack Stratton created the Wikipedia article for his band Vulfpeck in 2013 under the username Jbass3586; the article claimed that "the members met in a 19th-century German literature class at the University of Michigan" to add to the mythology of the band. Billboard picked this up in a 2013 interview article, and it was eventually added as a citation in the Wikipedia article.[39]

- In 2020, an editor inserted a false quote in the article of Antony Blinken, chosen by then President-elect Joe Biden for the position of Secretary of State. The quote, calling Vladimir Putin an "international criminal", was repeated in Russian media like Gazeta.Ru.[40]

- In 2007, an editor inserted (diff) an anecdote into Joseph Bazalgette's page about the diameter of London sewage pipes. The misinformation made it into newspaper articles and books - from the Institution of Civil Engineers, from The Spectator, from The Hindu, from the Museum of London (in modified form), two books these two, both about 'creative thinking.' Further details on the case can be found here. The information was not removed until 2021.

- In 2016, an IP-editor added three unsourced statements to Chamaki, a place in Iran: that 600 Assyrians used to populate the village, that the language spoken was Modern Assyrian and that the local church is called "Saint Merry". [sic] In a 2020 article from the Tehran Times, these same three statements were repeated.[41] No other sources have been found for these statements. While sources in Farsi may or may not exist for the population and language, this is unlikely for the "Saint Merry" spelling. The Tehran Times article was briefly used as a source before the likelihood of citogenesis was realized.

- It is well known that Zimbabwe experienced severe hyperinflation in 2008, but could you really trade one US dollar for 2,621,984,228,675,650,147,435,579,309,984,228 Zimbabwe dollars? A single-edit IP said so in 2015, along with reporting the country's unemployment rate to be 800% and quantitatively using the word "zillion". While the latter two remarks were innocently corrected within 3 days, the 34-digit figure stayed in place for 10 months before it was manually reverted, enough time to make it into at least one book.[42]

- Wikipedia has claimed at various times that Bill Gates's house is nicknamed Xanadu 2.0 and many online articles have repeated the claim, some of which are now cited by Wikipedia. No articles quote Gates or another authoritative source, but the moniker was used as the title of a 1997 article about the house.

- In 2006, an article entitled Onna bugeisha was added to English Wikipedia with the claim that it was a term referring to "a female samurai". The term does not exist in Japanese (it occasionally appears in works of fiction, referring to "female martial artists", onna meaning "woman" and bugeisha meaning "martial artist") and does not appear to have carried the meaning "female samurai" before the creation of this Wikipedia article. The article was translated into several foreign-language editions of Wikipedia—though not Japanese Wikipedia—and eventually the term started to appear in third-party blogs and online magazine articles, including National Geographic (both English and Spanish editions). In 2021, the article was moved to a compromise title, using a Japanese term that is used to refer to women warriors in pre-modern Japan, but seems to have been rarely used in English prior to 2020; within a few months, this term had also found its way into a number of online magazines in languages such as English and Polish.

- Since May 2010 the Playboy Bunny article claimed that Hugh Hefner "has stated that the idea for the Playboy bunny was inspired by Bunny's Tavern in Urbana, Illinois. [...] Hefner formally acknowledged the origin of the Playboy Bunny in a letter to Bunny's Tavern, which is now framed and on public display in the bar". No sources have been cited to support it. This information spread to a 2011 book, an article of the New Straits Times dated 22 January 2011, and an article of The Sun written in September 2017 and titled "This is the real reason that the Playboy girls were called Bunnies" (copied by the New York Post, too). Oldest and more reliable sources proved that the costume has been inspired by the Playboy mascot used since 1953. A partially readable photo of the tavern's letter showed that Hefner did not "formally acknowledged the origin of the Playboy Bunny" at all. Unfortunately this information spread to the French, the Spanish, the Catalan, and the Italian Wikipedias. The Catalan Wikipedia used the 2011 New Straits Times article to support it, while on the Italian Wikipedia The Sun article has been used as source.

- From 2008, the article on former Canadian prime minister Arthur Meighen claimed that he had been educated at Osgoode Hall Law School. In 2021, a reference to a 2012 newspaper article was added to support this claim. In fact, Meighen never attended law school, as several biographies (including a meticulously detailed three-volume work by Roger Graham) make clear. The author of the newspaper article seems to have found the inaccurate information on Wikipedia.

- In 2008, an uncited claim that a Croatian named "Mirko Krav Fabris" became Conclavist pope in 1978 was added to the article Conclavism. This information ended up in the second (but not the first) edition of the Historical Dictionary of New Religious Movements (2012). In 2014, the information was added that said Mirko Krav Fabris was a stand-up comedian with the stage name "Krav" who became pope as a joke and had died in 2012; the source given for this latter claim was a presentation of a stand-up comedian called Mirko Krav Fabris — who looks way too young to have been born before 1978 — in which it is neither mentioned that the person ever was a papal claimant in any form, nor that the person is dead. The 2015 book True or False Pope? Refuting Sedevacantism and Other Modern Errors published by the St. Thomas Aquinas Seminary of the SSPX makes an uncited claim that Mirko Krav Fabris was a Conclavist pope, a comedian with the stage name "Krav", and died in 2012.[43]

- According to Richard Herring, Wikipedia was the originator of the claim that he is primarily known as a (professional) ventriloquist. This was repeated in Stuff and then used as a reference for the claim in the article. He mentioned the incident on his podcast in 2021 (Nish Kumar - RHLSTP #315, at 54:47), describing the process of citogenesis without using the term itself.

- From 2012, Wikipedia claimed that the electric toaster was invented by a Scotsman named Alan MacMasters (archived Wikipedia biography, AfD resulting in deletion on July 22, 2022). This was a complete fabrication, which entered over a dozen books and numerous online sources, among them a BBC article and the website of the Hagley Museum and Library in Delaware, both subsequently cited in Wikipedia's MacMasters biography. As late as August 2022, Google still named MacMasters as the inventor of the electric toaster, citing the Hagley Museum.[44] Wikipedia criticism website Wikipediocracy published an interview with the hoaxer.[45]

- Between September 2007 and March 2022, the English Wikipedia article on Japanese admiral Jisaburō Ozawa stated that he was a whopping 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) tall. While Ozawa certainly was tall for a Japanese man of his era, with a 1965 book describing him as "over six feet",[46] this particular height appears to have been an invention, as the source following it made no claim of Ozawa's height at all. The uncited figure given in the article has subsequently appeared in at least four non-fiction books.[47][48][49][50]

- The term "Sproftacchel" was added as a synonym for photo stand-in on 15 February 2021 by an anon with no other contributions. No trace of the term before that date has been found, but as of July 2022 the term has been used by The New Zealand Herald,[51] Books for Keeps,[52] the Islington council,[53] the Hingham town council,[54] the city of Lincoln council[55] and we have "Sproftacchel Park" now.[56]

- In August 2008, an anonymous editor vandalised the page of Cypriot association football team AC Omonia to read that they have "a small but loyal group of fans called 'The Zany Ones'". They drew Manchester City in the UEFA Cup first round that year and a journalist at the Daily Mirror repeated the claim in both his match preview and report. The preview was then used as a source for this false statement.

- Triboulet: in 2007 an anonymous editor added a story about the jester slapping the king's buttocks to the article without citation. The story got later picked up in several articles, two of which were later added as citations to the article.

- U.S. National Public Radio was discovered to have published an article with false information lifted from a poorly-edited Wikipedia entry on the Turnspit Dog. The article referred to nonsensical Latin. "Vernepator Cur" is not real Latin. The phrase first appeared in an unsourced Wikipedia article in 2006 [1], and has since spawned hundreds of news articles repeating the false information.[2][3]

- The Transgender flag was unknown at the time of its Wikipedia article creation in 2006, and nomination for deletion in 2011 identified almost no Internet presence of the concept. Regardless, editors used the flag as an illustration in transgender topical articles, and the popularity of those articles popularized the flag as a symbol.

- Between November 2007 and April 2014, an anonymous editor added "hairy bush fruit" (毛木果, máo mù guǒ) to a list of Chinese names for kiwifruit. This term was repeated by The Guardian, which was later cited by the Wikipedia article as a source for the name.[57]

Terms that became real[edit]

In some cases, terms or nicknames created on Wikipedia have since entered common parlance, with false information thus becoming true.

- The term "Dunning–Kruger effect" did not originate on Wikipedia but it was standardized and popularized here. The underlying article had been created in July 2005 as Dunning-Kruger Syndrome, a clone of a 2002 post on everything2 that used both the terms "Dunning-Kruger effect" and "Dunning-Kruger syndrome".[58] Neither of these terms appeared at that time in scientific literature; the everything2 post and the initial Wikipedia entry summarized the findings of one 1999 paper by Justin Kruger and David Dunning. The Wikipedia article shifted entirely from "syndrome" to "effect" in May 2006 with this edit because of a concern that "syndrome" would falsely imply a medical condition. By the time the article name was criticised as original research in 2008, Google Scholar was showing a number of academic sources describing the Dunning–Kruger effect using explanations similar to the Wikipedia article. The article is usually in the top twenty most popular Wikipedia articles in the field of psychology, reaching number 1 at least once.

- In 2005, Wikipedia editors collectively developed a periodization of video game console generations, and gradually implemented it at History of video games and other articles.[59]

- In 2006, a Wikipedia editor claimed as a prank that the Pringles mascot was named "Julius Pringles." After the brand was sold from Procter & Gamble to Kellogg's, the name (sometimes modified slightly to "Julius Pringle") was adopted by official Pringles marketing materials.[60][61]

- In 2008, a then 17-year-old student added a claim that the coati was also known as "Brazilian aardvark". Although the edit was done as a private joke, the false information lasted for six years and was propagated by hundreds of websites, several newspapers, and even books by a few university presses.[62][24] The spread was such that the joke indeed became a common name for the animal and was cited in several sources. After the initial removal, the name was reinserted multiple times by users who believed it had become legitimate.

- Mike Trout's nickname: Mike Trout's article was edited in June 2012 with a nonexistent nickname for the Major League Baseball player, the "Millville Meteor"; media began using it, providing the article with real citations to replace the first fake ones. Although Trout was surprised, he did not dislike the nickname, signing autographs with the title.[63]

- Michelle/MJ's surname: the article for the then-unreleased film Spider-Man: Homecoming was edited in July 2017 with an unsourced claim that the mononymous character Michelle/MJ (portrayed by Zendaya) had the surname "Jones", a name used in works of fan fiction made in the lead up of the film; media reporting on the film then began using the surname, in spite of the character being kept mononymous by Sony Pictures and Marvel Studios through to its 2019 sequel Spider-Man: Far From Home. In the 2021 film Spider-Man: No Way Home, in confirming Michelle/MJ as a loose adaptation of Mary Jane Watson, the character was provided the expanded name of "Michelle Jones-Watson", making "Jones" a canon surname.[64]

- Riddler's alias: In November 2013, a Wikipedia editor named Patrick Parker claimed as a prank that "Patrick Parker" was also an alias of the DC Comics supervillain the Riddler,[65] the claim going unnoticed on the page for nine years.[66] In the 2022 film The Batman, this alias was made canon as a name used by Paul Dano's Riddler on his fake IDs, with a report by Comic Book Resources in April 2022 uncovering the act of citogenesis.[67] The name would see further use in the prequel comic book miniseries The Riddler: Year One.[68]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Michael V. Dougherty (21 May 2024). New Techniques for Proving Plagiarism: Case Studies from the Sacred Disciplines at the Pontifical Gregorian University. Leiden, Boston: Brill Publishers. p. 209. doi:10.1163/9789004699854. ISBN 978-90-04-69985-4. LCCN 2024015877. Wikidata Q126371346.

A published monograph that apparently copies many Wikipedia articles is now treated as an authority for later Wikipedia articles. This state of affairs is arguably not an optimal development.

- ^ Munroe, Randall. "Citogenesis". xkcd. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Special:Diff/719628400/721070227

- ^ McCauley, Ciaran (8 February 2017). "Wikipedia hoaxes: From Breakdancing to Bilcholim". BBC. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ "False fact on Wikipedia proves itself". 11 February 2009. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012.

- ^ "Medien: "Mich hat überrascht, wie viele den Fehler übernahmen"". Die Zeit. 13 February 2009. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ^ "Wikipedia article creates circular references".

- ^ a b "How pranks, hoaxes and manipulation undermine the reliability of Wikipedia". Wikipediocracy. 20 July 2014.

- ^ "Hirohito surrender broadcast".

- ^ "Hirohito surrender broadcast".

- ^ "Jewel Voice". GoogleBooks Ngram Viewer.

- ^ Talk:Hirohito surrender broadcast

- ^ Whetstone, David (8 November 2016). "Sir Roger Moore remembers co-star Tony Curtis and reveals his favourite Bond film". ChronicleLive. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Butterworth, Siobhain (3 May 2009). "Open door: The readers' editor on ... web hoaxes and the pitfalls of quick journalism". The Guardian – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Višnjić, Aleksandar; Veličković, Vladica; Milosavljević, Nataša Šelmić (2011). "QALY ‐ Measure of Cost‐Benefit Analysis of Health Interventions". Acta Facultatis Medicae Naissensis. 28 (4): 195–199.

- ^ Dr Panik (9 May 2014). "Were QALYs invented in 1956?". The Academic Health Economists' Blog.

- ^ Bartlett, Jamie (16 April 2015). "How much should we trust Wikipedia?". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ a b c d Harrison, Stephen (7 March 2019). "The Internet's Dizzying Citogenesis Problem". Future Tense - Source Notes. Slate Magazine. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ Ockham, Edward (2 March 2012). "Beyond Necessity: The medical condition known as glucojasinogen".

- ^ Allen, Nick. "Wikipedia, the 25-year-old student and the prank that fooled Leveson". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ "Leveson's Wikipedia moment: how internet 'research' on The Independent's history left him red-faced". The Independent. 30 November 2012.

- ^ Dewey, Caitlin. "The story behind Jar'Edo Wens, the longest-running hoax in Wikipedia history". The Washington Post.

- ^ Michael Harris (7 August 2014). The End of Absence: Reclaiming What We've Lost in a World of Constant Connection. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-698-15058-4.

- ^ a b Kolbe, Andreas (16 January 2017). "Happy birthday: Jimbo Wales' sweet 16 Wikipedia fails. From aardvark to Bicholim, the encylopedia of things that never were". The Register. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Ben Koo (9 October 2014). "Guilt by Wikipedia: How Joe Streater Became Falsely Attached To The Boston College Point Shaving Scandal". Awful Announcing.

- ^ Feiburg, Ashley (23 December 2015). "The 10 Best Articles Wikipedia Deleted This Week". Gawker.

- ^ Hardwick, Viv (9 September 2014). "Mears sets his sights on UK". The Northern Echo. Archived from the original on 29 September 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

He once hitchhiked around the Pacific Rim countries

- ^ Lijst van uitdrukkingen en gezegden F-J, diff on Dutch Wikipedia

- ^ NPO (23 March 2018). "De Tafel van Taal, de hond de jas voorhouden" – via YouTube.

- ^ Timmons, Heather; Yanofsky, David (21 April 2018). "Mike Pompeo's Gulf War service lie started on Wikipedia". Quartz. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ Moyer, Phillip (15 June 2019). "The case of an iconic watch: how lazy writers and Wikipedia create and spread fake "facts"". KSNV. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ Iris Bouwmeester (26 July 2017). "Door deze smiechten trapt heel Nederland al jaren in de Urker vistaart-hoax".

- ^ Special:Diff/966969824

- ^ Special:Diff/967708571

- ^ "YouTuber Poppy Is Engaged To Eric Ghoste". Access Hollywood. 10 July 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ Special:Diff/967760280/968057663

- ^ Dickson, EJ (29 July 2014). "I accidentally started a Wikipedia hoax". The Daily Dot. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Okyle, Carly. "Librarians React to 'Amelia Bedelia' Hoax". School Library Journal. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ State of the Vulf 2016

- ^ "Unreliable sources". meduza.io. Meduza. 27 November 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ "Historical churches in West Azarbaijan undergo rehabilitation works". Tehran Times. 4 August 2020. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ See "quotations" section: trillionaire

- ^ More information at: Talk:Conclavism § Pope Krav?

- ^ Rauwerda, Annie (12 August 2022). "A long-running Wikipedia hoax and the problem of circular reporting". Input.

- ^ "Wikipedia's Credibility Is Toast | Wikipediocracy". wikipediocracy.com.

- ^ Jay Gluck (1965). Ukiyo: Stories of "the Floating World" of Postwar Japan. Vanguard Press. p. 9. ISBN 9780814901083.

[Ozawa's] physical stature, over six feet, was massive for a Japanese [--]

- ^ Thomas McKelvey Cleaver (2017). Pacific Thunder: The US Navy's Central Pacific Campaign, August 1943–October 1944. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 76.

At 6 feet 7 inches, Ozawa was much taller than the average Japanese [--]

- ^ Merfyn Bourne (2013). The Second World War in the Air: The Story of Air Combat in Every Theatre of World War Two. Troubador Publishing Ltd. p. 293.

[Ozawa] was also very tall at six foot seven inches [--]

- ^ Tony Matthews (2021). Sea Monsters: Savage Submarine Commanders of World War Two. Simon and Schuster. p. 286.

At six-feet seven inches in height, Ozawa [--]

- ^ Arne Markland (2016). The Last Banzai: The Imperial Japanese Navy At Leyte Gulf. Lulu Press, Inc. p. 13.

Admiral Ozawa, tall for a Japanese at sixfoot seveninch [--]

- ^ Hanne, Ilona (2 April 2022). "Shakespeare celebrated throughout April in Stratford New Zealand". Stratford Press. Archived from the original on 4 April 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ "The Midnight Fair" (PDF). Reviews. Books for Keeps. No. 253. London. March 2022. p. 23. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ "3. Public consultation analysis". Consultation Results (PDF). islington.gov.uk (Report). Islington Council. 2022. p. 19. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ "Hingham Santa's Grotto". Reports (PDF). hinghamtowncouncil.norfolkparishes.gov.uk (Report). Annual Town Meetings. Hingham Town Council. April 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ "IMP Trail 2021" (PDF). Lincoln BIG Annual Report. Lincoln Business Improvement Group. June 2021. p. 10. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ "Comfort Station presents: "Sproftacchel Park"". logansquareartsfestival.com. Logan Square Arts Festival. June 2022. Archived from the original on 28 July 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ "In Praise of the Gooseberry". The Guardian. 28 July 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ https://everything2.com/title/Dunning-Kruger+Effect

- ^ Extension, Time (12 December 2022). "Is Wikipedia Really To Blame For Video Game Console Generations?". Time Extension. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Heinzman, Andrew (25 March 2022). "The Pringle Man's Name Is an Epic Wikipedia Hoax". Review Geek. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ Morse, Jack (25 March 2022). "The secret Wikipedia prank behind the Pringles mascot's first name". Mashable. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ Randall, Eric (19 May 2014). "How a raccoon became an aardvark". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ Lewis, Peter H. (20 September 2012). "Los Angeles Angels centerfielder Mike Trout is a phenom, but will it last?". ESPN.

- ^ Special:Diff/788391600/788391711

- ^ Special:Diff/580902127/581421492

- ^ Mannix, J. (14 November 2022). Are we gonna talk about the “Patrick Parker” portion? I’m pretty sure that was never an identity of his in the comics… – via Reddit.

Patrick D. Parker: Oh yeah, that was never in the comics, shows, movies, games or anything. [I] added that name, technically my name, to the wiki page for the Riddler back in 2013ish as one of the Riddler's aliases [as] a fun but dumb social experiment [to] test out how reliable Wikipedia was as a source [and] figured it would be taken down ages ago. Years go by and I forget about it. Jump to The Batman release and a friend texts me with a pic of the Riddler ID with my name [and] then it hit me. The writers must have done base level research on the Riddler, saw the name and thought it would be a neat little Easter egg for eagle eyed fans [only] what they ended up doing was taking a lie from the internet and made it into a truth by using that name as an alias for the Riddler so I have retroactively been made correct.

- ^ Cronin, Brian (2 April 2022). "Where Did Riddler Get the Aliases He Used in The Batman?". Comic Book Resources.

- ^ Jackson, Trey (28 February 2023). "The Riddler: Year One #3 Review". Batman On Film.