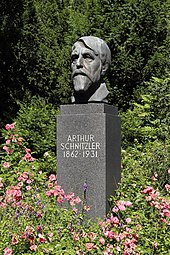

Arthur Schnitzler | |

|---|---|

Arthur Schnitzler, ca. 1912 | |

| Born | 15 May 1862[1] Vienna, Austria |

| Died | 21 October 1931 (aged 69) Vienna, Austria |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer and playwright |

| Language | German |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Genre | Short stories, novels, plays |

| Literary movement | Decadent movement, Modernism |

| Notable works | Liebelei, Reigen, Fräulein Else, Professor Bernhardi |

Arthur Schnitzler (15 May 1862 – 21 October 1931) was an Austrian author and dramatist. He is considered one of the most significant representatives of the Viennese Modernism. Schnitzler’s works, which include psychological dramas and narratives, dissected turn-of-the-century Viennese bourgeois life, making him a sharp and stylistically conscious chronicler of Viennese society around 1900.

Arthur Schnitzler was born at Praterstrasse 16, Leopoldstadt, Vienna, capital of the Austrian Empire (as of 1867, part of the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary). He was the son of a prominent Hungarian laryngologist, Johann Schnitzler (1835–1893), and Luise Markbreiter (1838–1911), a daughter of the Viennese doctor Philipp Markbreiter. His parents were both from Jewish families.[2] In 1879 Schnitzler began studying medicine at the University of Vienna and in 1885 he received his doctorate of medicine. He began work at Vienna's General Hospital (German: Allgemeines Krankenhaus der Stadt Wien), but ultimately abandoned the practice of medicine in favour of writing.

On 26 August 1903, Schnitzler married Olga Gussmann (1882–1970), a 21-year-old aspiring actress and singer who came from a Jewish middle-class family. They had a son, Heinrich (1902–1982), born on 9 August 1902. In 1909 they had a daughter, Lili, who committed suicide in 1928. The Schnitzlers separated in 1921. Schnitzler died on 21 October 1931 in Vienna of a brain haemorrhage. In 1938, following the Anschluss, his son Heinrich went to the United States and did not return to Austria until 1959; he is the father of the Austrian musician and conservationist Michael Schnitzler, born in 1944 in Berkeley, California, who moved to Vienna with his parents in 1959.[3]

Schnitzler's works were often controversial, both for their frank description of sexuality (in a letter to Schnitzler Sigmund Freud confessed "I have gained the impression that you have learned through intuition – although actually as a result of sensitive introspection – everything that I have had to unearth by laborious work on other persons")[4] and for their strong stand against antisemitism, represented by works such as his play Professor Bernhardi and his novel Der Weg ins Freie. However, although Schnitzler was Jewish, Professor Bernhardi and Fräulein Else are among the few clearly identified Jewish protagonists in his work.

Schnitzler was branded as a pornographer after the release of his play Reigen, in which 10 pairs of characters are shown before and after the sexual act, leading and ending with a prostitute. The furor after this play was couched in the strongest antisemitic terms.[5] Reigen was made into a French language film in 1950 by the German-born director Max Ophüls as La Ronde. The film achieved considerable success in the English-speaking world, with the result that Schnitzler's play is better known there under its French title. Richard Oswald's film The Merry-Go-Round (1920), Roger Vadim's Circle of Love (1964) and Otto Schenk's Der Reigen (1973) also are based on the play. A more recent adaptation is the Fernando Meirelles' film 360.

In the novella Fräulein Else (1924) Schnitzler may be rebutting a contentious critique of the Jewish character by Otto Weininger (1903) by positioning the sexuality of the young female Jewish protagonist.[6] The story, a first-person stream of consciousness narrative by a young aristocratic woman, reveals a moral dilemma that ends in tragedy.

In response to an interviewer who asked Schnitzler what he thought about the critical view that his works all seemed to treat the same subjects, he replied "I write of love and death. What other subjects are there?"[7] Despite his seriousness of purpose, Schnitzler frequently approaches the bedroom farce in his plays (and had an affair with Adele Sandrock, one of his actresses). Professor Bernhardi, a play about a Jewish doctor who turns away a Catholic priest in order to spare a patient the realization that she is on the point of death, is his only major dramatic work without a sexual theme.

A member of the avant-garde group Young Vienna (Jung-Wien), Schnitzler toyed with formal as well as social conventions. With his 1900 novella Leutnant Gustl, he was the first to write German fiction in stream-of-consciousness narration. The story is an unflattering portrait of its protagonist and of the army's obsessive code of formal honor. It caused Schnitzler to be stripped of his commission as a reserve officer in the medical corps – something that should be seen in the context of the rising tide of antisemitism of the time.

He specialized in shorter works like novellas and one-act plays. And in his short stories like "The Green Tie" ("Die grüne Krawatte") he showed himself to be one of the early masters of microfiction. However he also wrote two full-length novels: Der Weg ins Freie about a talented but not very motivated young composer, a brilliant description of a segment of pre-World War I Viennese society; and the artistically less satisfactory Therese.

In addition to his plays and fiction, Schnitzler meticulously kept a diary from the age of 17 until two days before his death. The manuscript, which runs to almost 8,000 pages, is most notable for Schnitzler's casual descriptions of sexual conquests; he was often in relationships with several women at once (most of his liaisons occurred with an embroiderer named “Jeanette”) and for a period of some years he kept a record of every orgasm. Collections of Schnitzler's letters also have been published.

Schnitzler's works were called "Jewish filth" by Adolf Hitler and were banned by the Nazis in Austria and Germany. In 1933, when Joseph Goebbels organized book burnings in Berlin and other cities, Schnitzler's works were thrown into flames along with those of other Jews, including Einstein, Marx, Kafka, Freud and Stefan Zweig.[8]

His novella Fräulein Else has been adapted a number of times, including the German silent film Fräulein Else (1929), starring Elisabeth Bergner, and the 1946 Argentine film The Naked Angel, starring Olga Zubarry.

The majority of Schnitzler's archive, which consists of 40,000 pages worth of documents, was saved from the Nazis by a British man, Eric A. Blackall. Acting at the behest of Schnitzler's widow (actually his ex-wife), Olga, Blackhall arranged for the documents to be secretly transported to Cambridge University under a diplomatic seal. After the war, this created a tricky legal situation, as Schnitzler's ex-wife, Olga did not have the legal right to donate the documents. In fact, Schnitzler had bequeathed them to his son, Heinrich, who was not in Vienna at the time.[9] During the Second World War and afterwards, Heinrich Schnitzler tried to get the documents back but did not succeed. Thomas Trenkler wrote in an article in the newspaper, Kurier, that the acquisition of the documents by British forces was not legitimate and that the documents should be handed to Schnitzler's remaining family in 2015.[10] Schnitzler's grandsons, Michael and Peter, announced that they indeed wanted the documents handed over to them.