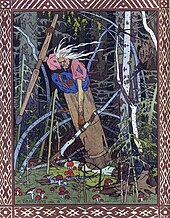

Baba Yaga is an enigmatic or ambiguous character from Slavic folklore (or one of a trio of sisters of the same name) who has two opposite roles. In some motifs she is described as a repulsive or ferocious-looking old woman who fries and eats children, while in others she is a nice old woman, who helps out the hero.[1] She is often associated with forest wildlife. Her distinctive traits are flying around in a wooden mortar, wielding a pestle, and dwelling deep in the forest in a hut standing on chicken legs.

Variations of the name Baba Yaga are found in many Slavic languages. The first element is a babble word which gives the word бабуся (babusya or 'grandmother') or babusia in modern Ukrainian and Polish respectively, бабушка (babushka or 'grandmother') in modern Russian, and babcia or babunia ('grandmother') in Polish. In Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, and Bulgarian, baba means 'grandmother' or 'old woman'. In contemporary Polish and Russian, baba is the pejorative synonym for 'woman', especially one that is old, dirty or foolish. As with other kinship terms in Slavic languages, baba may be used in other ways, potentially as a result of taboo; it may be applied to various animals, natural phenomena, and objects, such as types of mushrooms, cake or pears. In the Polesia region of Ukraine, the plural baby may refer to an autumn funeral feast. The element may appear as a means of glossing the second element, iaga, with a familiar component or may have also been applied as a means of distinguishing Baba Yaga from a male counterpart.[2]

Yaga is more etymologically problematic and there exists no clear consensus among scholars about its meaning. In the 19th century, Alexander Afanasyev proposed the derivation of Proto-Slavic *ož and Sanskrit ahi ('serpent'). This etymology has been explored by 20th-century scholars. Related terms appear in Serbian and Croatian jeza ('horror', 'shudder', 'chill'), Slovene jeza ('anger'), Old Czech jězě ('witch', 'legendary evil female being'), modern Czech jezinka ('wicked wood nymph', 'dryad'), and Polish jędza ('witch', 'evil woman', 'fury'). The term appears in Old Church Slavonic as jęza/jędza ('disease'). In other Indo-European languages the element iaga has been linked to Lithuanian engti ('to abuse (continuously)', 'to belittle', 'to exploit'), Old English inca ('doubt', 'worry", 'pain'), and Old Norse ekki ('pain', 'worry').[3]

Vladimir Propp wrote that depictions of Baba Yaga taken from various fairy tales do not create a coherent image.[4]

The first clear reference to Baba Yaga (Iaga baba) occurs in 1755 in Mikhail V. Lomonosov's Russian Grammar. In Lomonosov's grammar book, Baba Yaga is mentioned twice among other figures largely from Slavic tradition. The second of the two mentions occurs within a list of Slavic gods and beings next to their presumed equivalence in Roman mythology (the Slavic god Perun, for example, appears equated with the Roman god Jupiter). Baba Yaga, however, appears in a third section without an equivalence, highlighting her perceived uniqueness even in this first known attestation.[5]

In the narratives in which Baba Yaga appears, she displays a number of distinctive attributes: a turning, chicken-legged hut; and a mortar, pestle, and/or mop or broom. Baba Yaga may ride on the broom or, most recognizably, inside a mortar, using the broom to sweep away her tracks.[1] Russian ethnographer Andrey Toporkov explains Baba Yaga's selection of tools by numerous pagan rituals involving women. He suggests that the pestle was first to be used by Baba Yaga, because it may be used as a weapon (as such, it was used in a number of rituals) and the mortar was added later by an association.[6]

Baba Yaga often bears the epithet Baba Yaga kostyanaya noga ('bony leg'), or Baba Yaga s zheleznymi zubami ('with iron teeth')[7] and when inside her dwelling, she may be found stretched out over the stove, reaching from one corner of the hut to another. Baba Yaga may sense and mention the russkiy dukh ('Russian scent') of those that visit her. Her nose may stick into the ceiling. Particular emphasis may be placed by some narrators on the repulsiveness of her nose, breasts, buttocks, or vulva.[8]

Sometimes Baba Yaga is said to live in the Faraway or Thrice-ninth Tsardom: "Beyond the thrice-nine kingdoms, in the thirtieth realm, beyond the fiery river, lives the Baba Yaga."[9] In some tales, a trio of Baba Yagas appears as sisters, all sharing the same name. For example, in a version of "The Maiden Tsar" collected in the 19th century by Alexander Afanasyev, Ivan, a handsome merchant's son, makes his way to the home of one of three Baba Yagas:[10]

He journeyed onwards, straight ahead ... and finally came to a little hut; it stood in the open field, turning on chicken legs. He entered and found Baba Yaga the Bony-legged. "Fie, fie," she said, "the Russian smell was never heard of nor caught sight of here, but it has come by itself. Are you here of your own free will or by compulsion, my good youth?" "Largely of my own free will, and twice as much by compulsion! Do you know, Baba Yaga, where lies the thrice tenth kingdom?" "No, I do not," she said, and told him to go to her second sister; she might know..

Ivan walks for some time before encountering a small hut identical to the first. This Baba Yaga makes the same comments and asks the same question as the first, and Ivan asks the same question. This second Baba Yaga does not know either and directs him to the third, but says that if she gets angry with him "and wants to devour you, take three horns from her and ask her permission to blow them; blow the first one softly, the second one louder, and third still louder." Ivan thanks her and continues on his journey.

After walking for some time, Ivan eventually finds the chicken-legged hut of the youngest of the three sisters turning in an open field. This third and youngest of the Baba Yagas makes the same comment about "the Russian smell" before running to whet her teeth and consume Ivan. Ivan begs her to give him three horns and she does so. The first he blows softly, the second louder, and the third louder yet. This causes birds of all sorts to arrive and swarm the hut. One of the birds is the firebird, which tells him to hop on its back or Baba Yaga will eat him. He does so and the Baba Yaga rushes him and grabs the firebird by its tail. The firebird leaves with Ivan, leaving Baba Yaga behind with a fistful of firebird feathers.

In Afanasyev's collection of tales, Baba Yaga also appears in "Baba Yaga and Zamoryshek", "By Command of the Prince Daniel", "Vasilisa the Fair", "Marya Moryevna", "Realms of Copper, Silver, and Gold", "The Sea Tsar and Vasilisa the Wise", and "Legless Knight and Blind Knight" (English titles from Magnus's translation).[11]

Andreas Johns describes Baba Yaga as "one of the most memorable and distinctive figures in eastern European folklore", and observes that she is "enigmatic" and often exhibits "striking ambiguity".[12] He characterizes Baba Yaga as "a many-faceted figure, capable of inspiring researchers to see her as a Cloud, Moon, Death, Winter, Snake, Bird, Pelican or Earth Goddess, totemic matriarchal ancestress, female initiator, phallic mother, or archetypal image".[2]

Baba Yaga appears on a variety of lubki (singular lubok), wood block prints popular in late 17th and early 18th century Russia. In some instances, Baba Yaga appears astride a pig going to battle against a reptilian entity referred to as "crocodile". Dmitry Rovinsky interpreted this scene as a political parody. Peter the Great persecuted Old Believers, who in turn referred to him as a crocodile. Rovinsky notices that some lubki feature a ship below the crocodile, interpreted as a hint to the rule of Peter the Great, while Baba Yaga dressed in A Finnish dress ("chukhonka dress") is a hint to Peter the Great's wife Catherine I, sometimes derisively referred to as the chukhonka ('Finnish woman'). A lubok that features Baba Yaga dancing with a bagpipe-playing bald man has been identified as a merrier depiction of the home life of Peter and Catherine.[13] [14] Some other scholars[who?] have interpreted these lubki motifs as reflecting a concept of Baba Yaga as a shaman. The "crocodile" would in this case represent a monster who fights witches, and the print would be something of a "cultural mélange" that "demonstrate[s] an interest in shamanism at the time".[15]

According to Andreas Johns, "Neither of these two interpretations significantly changes the image of Baba Yaga familiar from folktales. Either she can be seen as a literal evil witch, treated somewhat humorously in these prints, or as a figurative 'witch', an unpopular foreign empress. Both literal and figurative understandings of Baba Yaga are documented in the nineteenth century and were probably present at the time these prints were made."[15]

Ježibaba, a figure closely related to Baba Yaga, occurs in the folklore of the West Slavic peoples. The two figures may originate from a common figure known during the Middle Ages or earlier; both figures are similarly ambiguous in character, but differ in appearance and the different tale types they occur in. Questions linger regarding the limited Slavic area—East Slavic nations, Slovakia, and the Czech lands—in which references to Ježibaba are recorded.[16] Jędza, another figure related to Baba Yaga, appears in Polish folklore.[17]

Similarities between Baba Yaga and other beings in folklore may be due to either direct relation or cultural contact between the Eastern Slavs and other surrounding peoples.[citation needed] In Central and Eastern Europe, these figures include the Bulgarian gorska maika (Горска майка', 'Forest Mother', also the name of a flower); the Hungarian vasorrú bába ('Iron-nose Midwife'), the Serbian Baba Korizma, Gvozdenzuba ('Iron-tooth'), Baba Roga (used to scare children in Bosnia, Croatia, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia), šumska majka ('Forest Mother'), and the babice; and the Slovenian jaga baba or ježibaba, Pehta or Pehtra baba and kvatrna baba or kvatrnica. In Romanian folklore, similarities have been identified in several figures, including Mama padurii ('Forest Mother') or Baba Cloanta referring to the nose as a bird's beak. In neighboring Germanic Europe, similarities have been observed between the Alpine Perchta and Holda or Holle in the folklore of Central and Northern Germany, and the Swiss Chlungeri.[18]

Some scholars have proposed that the concept of Baba Yaga was influenced by East Slavic contact with Finno-Ugric and Siberian peoples. The "hut on chicken legs deep in the forest" plainly resembles huts raised on one or several stilts using stump with roots for the stilts, in popular use by Finno-Ugric peoples and also found in forests rather than villages. The stumps with roots may be uprooted and laid in a new place as in the example exhibited in Skansen, or in ground where it was felled. Like Baba Yaga's hut, these are normally cramped for a person, though unlike Baba Yaga's house they do not actively walk and also do not contain a stove, being intended as storehouses and not for living.[19] The Karelian Syöjätär has some aspects of Baba Yaga, but only the negative ones, while in other Karelian tales, helpful roles akin to those from Baba Yaga may be performed by a character called akka ('old woman').[20]

Mussorgsky's 1874 suite Pictures at an Exhibition has a movement titled "The Hut on Hen's Legs (Baba Yaga)". The rock adaptation of this piece recorded by the English progressive rock band Emerson, Lake & Palmer includes a two-part track "The Hut of Baba Yaga", interrupted by "The Curse of Baba Yaga" (movements 8 to 10).[21] Animated segments telling the story of Baba Yaga were used in the 2014 documentary The Vanquishing of the Witch Baba Yaga, directed by American filmmaker Jessica Oreck.[22] GennaRose Nethercott's first novel, Thistlefoot, "reimagines Baba Yaga as a Jewish woman living in an Eastern European shtetl in 1919, during a time of civil war and pogroms."[23] Sophie Anderson's book The House With Chicken Legs, which received various accolades,[24][25][26][27] features Marinka, the granddaughter of Baba Yaga. Here "Yaga" is not a name, but a title for the guardian who guides the dead into the afterlife, and Marinka is being trained for this role. Yagas are reimagined as kind and benevolent.[28][29]