| Part of a series on |

| Anabaptism |

|---|

|

|

|

Conrad Grebel (c. 1498 – 1526) was a co-founder of the Swiss Brethren movement.

| Part of a series on |

| Anabaptism |

|---|

|

|

|

Conrad Grebel (c. 1498 – 1526) was a co-founder of the Swiss Brethren movement.

Conrad Grebel was born, probably in Grüningen in the canton of Zürich, about 1498 to Junker Jakob and Dorothea (Fries) Grebel, the second of six children. He spent his early life in Grüningen, and then came to Zürich with his family around 1513. He spent several years abroad in study, worked as a proofreader in Basel, married in 1522, and became a Christian minister around 1523.

Conrad Grebel is thought to have studied for six years at the Carolina, the Latin school of the Grossmünster Church in Zürich. He enrolled at the University of Basel in October 1514. While there he studied under Heinrich Loriti, a noted humanist scholar. His father acquired a stipend from Emperor Maximilian for Conrad to study at the University of Vienna. In 1515 he began attending there and remained until 1518. While there, Grebel developed a close friendship with Joachim Vadian,[a] an eminent Swiss humanist professor from St. Gall. After spending three years in Vienna he returned to Zürich for about three months. His father acquired a scholarship for Conrad from the King of France to attend the University in Paris. He spent two years in study there, and joined the boarding academy of his former teacher in Basel, Loriti. In Paris Grebel engaged in a loose lifestyle, and was involved in several brawls with other students. When Grebel's father received word of his son's demeanor, he cut off Conrad's funds and demanded that he return to Zürich. Conrad Grebel spent about six years in three universities, but without finishing his education or receiving a degree.

In 1521 Grebel joined a group gathered to study with Huldrych Zwingli. With him they studied the Greek classics, the Latin Bible, the Hebrew Old Testament and the Greek New Testament. It was in this study group that Grebel met and developed a close friendship with Felix Manz.

Conrad Grebel probably experienced a conversion in the spring of 1522. His life showed a dramatic change, and he became an earnest supporter of the preaching and reforms of Zwingli. He rose to leadership among Zwingli's young and enthusiastic followers. This close following and enthusiastic support of Zwingli was challenged by the Second Disputation[b] in Zürich in October 1523. Grebel and Zwingli broke over abolishing the Mass. Zwingli argued before the council for abolishing the Mass and removing images from the church. But when he saw that the city council was not ready for such radical changes, he chose not to break with the council, and even continued to officiate at the Mass until it was abolished in May 1525. Grebel saw this as an issue of obeying God rather than men, and, with others, could not conscientiously continue in that which they had condemned as unscriptural. These young radicals felt betrayed by Zwingli, while Zwingli looked on them as irresponsible.

About 15 men broke with Zwingli, and, while taking no specific action at that time, they regularly met together for prayer, fellowship and Bible study. During this time of waiting for direction from God, they sought religious connections outside of Zürich. Grebel wrote to both Andreas Karlstadt and Martin Luther in the summer of 1524, and to Thomas Müntzer in September. Karlstadt traveled to Zürich and met with them in October of that year. Despite apparent similarities, no connection between the Zürich radicals and Karlstadt ever came to fruition. In his letter to Müntzer, Grebel encouraged Müntzer in his opposition to Luther, but also reproached him for several errors he felt he was making. He urged Müntzer not to take up arms. The letter was returned to Grebel, having never reached Müntzer.

The final question to completely sever ties between the radicals and Zwingli was the question of infant baptism. A public debate was held on 17 January 1525. Zwingli argued against Grebel, Manz and George Blaurock. The city council decided in favor of Zwingli and infant baptism, ordered the Grebel group to cease their activities, and ordered that any unbaptized infants must be submitted for baptism within 8 days. Failure to comply with the council's order would result in exile from the canton. Grebel had an infant daughter, Issabella, who had not been baptized, and he resolutely stood his ground. He did not intend for her to be baptized.

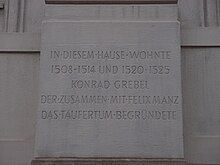

The group met together for counsel on 21 January in the home of Felix Manz. This meeting was illegal according to the new decision of the council. George Blaurock asked Grebel to baptize him upon a confession of faith.[c] Afterward, Blaurock baptized the others who were present. As a group they pledged to hold the faith of the New Testament and live as fellow disciples separated from the world. They left the little gathering full of zeal to encourage all men to follow their example.

Being well known in Zürich, Grebel left the work to others and set out on an evangelistic mission to the surrounding cities. In February, Grebel baptized Wolfgang Ulimann by immersion in the Rhine River. Ulimann was in St. Gall, and Grebel traveled there in the spring. Conrad Grebel and Wolfgang Ulimann spent several months preaching with much success in the area of St. Gall. In the summer he went to Grüningen and preached with great effect. In October 1525 he was arrested and imprisoned. While in prison, Grebel was able to prepare a defense of the Anabaptist position on baptism.[1] Through the help of some friends, he escaped in March 1526. He continued his ministry and was at some point able to get his pamphlet printed. Grebel removed to the Maienfeld area in the Canton of Grisons (where his oldest sister lived). Shortly after arrival he died, probably around July or August.

The extant works of Conrad Grebel consist of 69 letters written by him from September 1517 to July 1525, three poems, a petition to the Zürich council, and portions of a pamphlet written by him against infant baptism, as quoted by Zwingli in his counterarguments. Three letters written to Grebel (Benedikt Burgauer, 1523; Vadian, 1524; and Erhard Hegenwalt, 1525) have been preserved. The majority of the 69 letters written by Grebel are from his student years, however, and shed little light on his ministry as an Anabaptist.

Though his entire life was less than 30 years, his Christian ministry was compressed into less than four years, and his time as an Anabaptist was only about a year and a half, Conrad Grebel's impact earned him the title "the Father of Anabaptists".[d] Grebel performed the first known adult baptism associated with the Reformation, and was referred to as the "ringleader" of the Anabaptists in Zürich. Zwingli complained of no major differences with Grebel on cardinal points of theology, and minimized Grebel's differences as "unimportant outward things, such as these, whether infants or adults should be baptized and whether a Christian may be a magistrate." Yet these differences reveal a deep division of thought on the nature of the church, and the relationship of the church and the Christian to the world. The beliefs of Conrad Grebel and the Swiss Brethren have left an impression on the life and thought of Amish, Baptist, Schwarzenau Brethren/German Baptist, and Mennonite churches, as well as numerous pietistic and free church movements. The Bruderhof Communities, founded in 1920,[2] draw inspiration from the beliefs and actions of Conrad Grebel and the other reformation era Anabaptists.[3] Where others only longed for restitution or shrank from too much reform, Grebel and his group acted decisively and at great personal risk. Freedom of conscience and separation of church and state are two great legacies of the Anabaptist movement initiated by these Swiss Brethren.

With Petr Chelčický (1390–1460) of Bohemia, Conrad Grebel is considered one of the first nonresistant Christians of the Reformation.

In 1961 a Mennonite University College was named after him in Waterloo, Ontario.

The Grebels had been a prominent Swiss family for over a century before Conrad's birth. His father Jakob was an iron merchant and served as a magistrate in Grüningen from 1499 to 1512. After that he served as a representative on the council of the Canton of Zürich, and was also frequently called upon as an ambassador for Zürich to meetings of the Swiss Confederation. Jakob Grebel disagreed with his son's religious sentiments, but he also thought Zwingli's measures against the Anabaptists were too harsh. Jakob Grebel was executed in Zürich on 30 October 1526, having been convicted of receiving illegal funds from foreign rulers. Some scholars consider his opposition to the measures of Zwingli as a likely reason behind the execution.

Against his family's wishes, Conrad Grebel married Barbara on 6 February 1522[citation needed]. Children were born to this union, and relatives raised the children after the death of Conrad. Ironically, the children were raised in the Reformed faith, and the family name once again became prominent in Zürich. His grandson, also named Conrad, was the city's treasurer in 1624, and a later descendant also named Conrad Grebel was burgomaster in 1669. Even in recent times, Grebel descendants have served the courts and parishes of Zürich.

In 1961 a Mennonite University College, Conrad Grebel University College, was named after him in Waterloo, Ontario.[4]