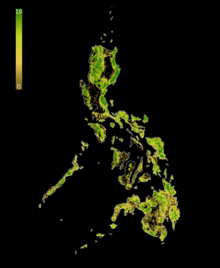

As in other Southeast Asian countries, deforestation in the Philippines is a major environmental issue. Over the course of the 20th century, the forest cover of the country dropped from 70 percent down to 20 percent.[1] Based on an analysis of land use pattern maps and a road map an estimated 9.8 million hectares of forests were lost in the Philippines from 1934 to 1988.[2]

A 2010 land cover mapping by the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority (NAMRIA) revealed that the total forest cover of the Philippines is 6,839,718 hectares (68,397.18 km2) or 23% of the country's total area of 30,000,000 hectares (300,000 km2).[3]

Deforestation affects biodiversity in the Philippines and has long-term negative impacts on the country's food production.[4] Deforestation in the Philippines has also been associated with floods, soil erosion, deaths, and damage to property.[5]

It is unknown the percentage of forest the Spaniards found in the Philippines in 1521, before and during the Spanish colonial period, 380 years, some land was cleared for agriculture, roads and cities, and in 1900, more than 70% of the country was still covered by jungles. But after 46 years of American and Japanese occupation, more than 20% of forest was destroyed, and by the end of the 20th century, only 20% of the country was covered by forest.[6]

Forest clearing was notable in the Visayas, particularly in the islands of Negros, Bohol and Cebu, where much of the forest cover had already been lost. Agricultural expansion continued throughout the 20th century.[7]

Indigenous peoples, such as the such as the Yapayao and Isneg peoples who used to live in the Ilocos Region, were slowly pushed into living in the sparsely populated but resource-rich mountains, which would expose them to conflicts with developers in later eras, particularly during Martial Law under Ferdinand Marcos.[8]: 47

The 1960s and 1970s saw a boom in the logging industry,[9] with the industry reaching its peak during the era of President Ferdinand Marcos.[10]

Under Marcos, logging took on an increasingly central role in the Philippine economy.[11] Following the declaration of martial law in 1972, Marcos handed out concessions to large tracts of land to his senior military officials, cronies,[12] and relatives.[13] The government encouraged log exportation to Japan resulting from soaring wood demand during Japan's period of rapid economic growth,[14] and pressure to pay foreign debt. Forests resources were exploited by set-up companies and reforestation was rarely undertaken.[9] Japanese log traders purchased massive quantities of cheap logs from unsustainable sources, accelerating deforestation.[15] Log production increased from 6.3 million cubic metres (220×106 cu ft) in 1960 to an average of 10.5 million cubic metres (370×106 cu ft) between 1968 and 1975, peaking at over 15 million cubic metres (530×106 cu ft) in 1975, before declining to about 4 million cubic metres (140×106 cu ft) in 1987.[11] The 1970s and 1980s saw an average of 2.5% of Philippine forests disappearing every year, which was thrice the worldwide deforestation rate.[16]

Deforestation remained very high during the Corazon Aquino and Fidel V. Ramos administrations despite tree planting efforts due to corruption and inefficiency in the government agencies involved.[9]

According to Global Forest Watch, from 2001 to 2020, most of the loss of forest cover in the Philippines took place in Palawan. Other provinces that have lost significant forest cover are Agusan del Sur, Zamboanga del Norte, Davao Oriental, and Quezon Province.[17]

According to scholar Jessica Mathews, short-sighted policies by the Filipino government have contributed to the high rate of deforestation:[18]

The government regularly granted logging concessions of less than ten years. Since it takes 30–35 years for a second-growth forest to mature, loggers had no incentive to replant. Compounding the error, flat royalties encouraged the loggers to remove only the most valuable species. A horrendous 40 percent of the harvestable lumber never left the forests but, having been damaged in the logging, rotted or was burned in place. The unsurprising result of these and related policies is that out of 17 million hectares of closed forests that flourished early in the century only 1.2 million remain today.

Attribution of deforestation to population pressure or agricultural expansion was found not to be backed by existing evidence in a 1992 study.[19] Subsequent research has shown that intensification of existing farmers and improved off-farm income reduced forest pressure.[20] However, in some parts of the country forest encroachment still happens due to high demand for vegetables.[21]

Mining and logging are major causes of deforestation in the Philippines.[22][23][24] Mining operations have cleared large areas of forest land and has led to water contamination, ecological destruction, loss of livelihood,[25] and loss of biodiversity.[26]

Republic Act 7942, or the Philippine Mining Act, allows mining operations to clear trees and relocate Indigenous and local communities.[27] The law allows foreign-owned companies to engage in mining activities. According to environmental group Alyansa Tigil Mina, the law "legitimizes the plunder of our national patrimony," and that the "situation will only worsen if ChaCha prospers and transnational corporations are allowed to act with impunity."[28]

Illegal logging occurs in the Philippines[29] and intensifies flood damage in some areas.[30]

Destructive typhoons in the Philippines, such as Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda) in 2013, also cause deforestation and defoliation.[31][32]

The Philippine national REDD+ Strategy, which aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation, was drafted and submitted to the United Nations in 2010.[33] An update to the strategy published by the Forest and Management Bureau of the Philippines showed that as of 2017, the county was still in the early phase of preparing to implement its REDD+ Strategy.[34]

Executive Order 23 was signed in February 2011 banning logging throughout the country.[35]

New mining agreements were banned in 2012 to protect the environment, though existing mines were allowed to continue operations.[36]

A nationwide ban on open-pit mining was put in place in 2017. Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Secretary Gina Lopez suspended permits for 26 mining operations that violated environmental rules. The ban on open-pit and other mining operations was lifted in 2021.[27]

In June 1977, President Ferdinand Marcos signed a law requiring the planting of one tree every month for five consecutive years by every citizen of the Philippines.[37] The law was repealed by President Corazon Aquino in July 1987,[38] through Executive Order 287, which states that the planting of trees "can be achieved without the compulsion and the penalties for non-compliance therewith as set forth in the Decree".[39]

President Benigno Aquino III established the National Greening Program (NGP)[40] with the signing of Executive Order No. 26 on February 24, 2011.[41] The program aims to increase the country's forest cover in 1.5 million hectares (15,000 km2) of land with 1.5 billion trees from 2011 to 2016. In 2015, the program was expanded to cover all remaining unproductive, denuded and degraded forestlands and its period of implementation extended from 2016 to 2028.[42]

In September 2012, President Benigno Aquino III signed a law requiring all able-bodied citizens of the Philippines, who are at least 12 years of age, to plant one tree every year.[43] There is no provision in the law to enforce and monitor compliance to this requirement.

In June 2020, the DENR started allowing a "family approach" under the National Greening Program, permitting families to establish forest plantations composed of timber and non-timber species, which include bamboo and rattan.[44]

There are tree-planting initiatives conducted in various parts of the country. On March 8, 2012, 1,009,029 mangrove trees were planted within one hour by a team achieved by the joint efforts of Governor Lray Villafuerte of the El Verde Movement and the people of San Rafael of Ragay, Camarines Sur.[45]

On September 26, 2014, the Philippines broke the Guinness World Record for the "Most trees planted simultaneously (multiple locations)", wherein 2,294,629 trees were planted in 29 locations throughout the country by 122,168 participants in an event organized by TreeVolution: Greening MindaNOW (Philippines). Trees planted during the event included rubber, cacao, coffee, timber, mahogany trees, as well as various fruit trees and other species native to the country.[46]

In May 2019, the House of Representatives of the Philippines has approved House Bill 8728, or the "Graduation Legacy for the Environment Act," principally authored by Magdalo Party-List Representative Gary Alejano and Cavite 2nd District Representative Strike Revilla, requiring all graduating elementary, high school, and college students to plant at least 10 trees each before they can graduate.[47] A similar Senate bill was filed but not passed.[38]

House Bill 5240, or the National Land Use Act, and House Bill 9088, or the Sustainable Forest Management Act, were approved in the House of Representatives to address deforestation, land use conversion, and other environmental issues. The counterpart bills in the Senate stalled in the committee on the environment.[48]

Environmental groups have called for a review the Philippine Mining Act, the Fisheries Code, the Comprehensive Land Use Plan, and the Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System Act to ensure responsible environmental and natural resources management. Environmental groups have also called for the passage of a People's Mining Law and an Environmental Defender's Law.[28]

Local governments, Indigenous communities, and nongovernmental organizations conduct campaigns against destructive practices such as logging and mining. Organizations include Alyansa Tigil Mina and Kalikasan People's Network for the Environment.[27][49]

The killing of environmental activists have been allegedly linked to mining companies. According to human rights group Global Witness, a third of land defenders killed in the Philippines from 2012 to 2024 are anti-mining activists.[28]