American modern-dance choreographer and dancer

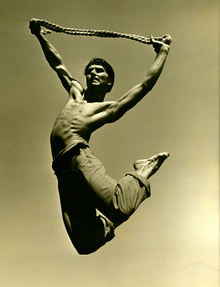

Frederick "Erick" Hawkins (April 23, 1909 – November 23, 1994) was an American modern-dance choreographer and dancer.[1]

Early life

Frederick Hawkins was born in Trinidad, Colorado, on April 23, 1909. He majored in Greek civilization at Harvard University, graduating in 1932 (although Class of 1930).[2] A performance by the German dancers Harald Kreutzberg and Yvonne Georgi so impressed him that he went to Austria to study dance with the former. Later, he studied at the School of American Ballet.[1]

Career

Soon, he was dancing with George Balanchine's American Ballet. In 1937, he choreographed his first dance, Show Piece, which was performed by Ballet Caravan. The next year, Hawkins was the first man to dance with the company of the famous modern dancer and choreographer Martha Graham. In 1939, he officially joined her troupe, dancing male lead in a number of her works, including Appalachian Spring in 1944. They married in 1948. He left her troupe in 1951 to found his own, and they divorced in 1954.

Not long afterwards, he met and began working alongside the experimental composer Lucia Dlugoszewski. They married and remained together for the rest of his life.[3]

After leaving the Graham Company, Hawkins' work developed in a quite different direction. He moved away from esthetic visions based on realistic psychology, sociopolitical themes, storylines or musical portrayals, towards one inspired by ritual and mysticism that called upon dancers' kinesthetic responses to celebrate human, animal and other natural phenonmema.[4] Major influences included Native-American dance rituals and folklore, Japanese esthetics and Zen, and various schools of dance, theater and philosophical thought from around the world, including East Asian and Ancient Greek classics.[1][5] In some ways, he took dance in a similar direction that abstract painters were taking art, though he disliked the label 'abstract'.

In a personal quest for dance safety,[a] Hawkins set out to integrate anatomic principles with dance.[6] He developed an innovative approach to dance technique based on the movement principles of kinesiology and anatomic study, thereby also creating a bridge to later somatic practices.[6] He advocated familiarity with ideokinesis (as well as other somatic approaches to training) and the acquisition of what he termed a 'thinkfeel' sensory awareness of the body and its movement.[6]

In contrast to the intense contractions and shaped positions typical of the Graham technique, Hawkins favored muscular release and free-flowing patterns of movement in a pursuit of effortless movement and seamless transitions.[6] He famously stated “The body is a clear place.” Overall, his dance technique may be seen to combine kinesiology, modern dance (including Graham technique) and a particular idea of beauty.[6]

Hawkins championed contemporary composers, and insisted on performing to live music. The Erick Hawkins Dance Company toured with the Hawkins Theatre Orchestra, an ensemble of seven or more instrumentalists plus conductor. In addition to his wife, Dlugoszewski, prominent composers of the time with whom he worked included Henry Cowell, David Diamond, Ross Lee Finney, Lou Harrison, Alan Hovhaness, Wallingford Riegger, Toru Takemitsu and Virgil Thomson.[4][8] Collaborating visual artists include Isamu Noguchi, Ralph Dorazio, Barbara Morgan,[9] Helen Frankenthaler, and Robert Motherwell.

Award and death

In 1988, Hawkins received the Scripps award at the American Dance Festival. On October 14, 1994, one month before he died, he was presented with the National Medal of Arts by President Bill Clinton.[10] Hawkins died at Lenox Hill Hospital in Manhattan in November 1994. At the time of his death, he was survived by his wife, Dlugoszewski, and by his sister, Murial Wright Davis.[1]

Legacy

The Erick Hawkins Dance Company has continued after the death of its founder. Dlugoszewski initially took over as artistic director until her death in 2000, during which time she choreographed four new works.[11][b] Katherine Duke, who was appointed artistic director of the company in 2001, has been charged with supervising both the teaching of Hawkins' technique and the continuation of his repertory.[12]

Works

Works choreographed by Erick Hawkins [13]

1930s

- Showpiece (1937) premiered Bennington College, Bennington, Vermont. Dancers: Members of Ballet Caravan. Music by Robert McBride

1940s

- Insubstantial Pageant (1940) premiered 92nd Street Y, New York, NY. Dancer: Erick Hawkins. Music by Lehman Engel

- In Time of Armament (1941) premiered 92nd Street Y, New York, NY. Dancer: Erick Hawkins. Music by Hunter Johnson

- Liberty Tree (1941), premiered 92nd Street Y, New York, NY. Dancer: Erick Hawkins. Music by Ralph Gilbert

- Trickster Coyote (1941), (revived in 1965 and 1983) premiered 92nd Street Y, New York, NY. Dancer: Erick Hawkins. Music by Henry Cowell

- Curtain Raiser (1942) premiered 92nd Street Y, New York, NY. Dancer: Erick Hawkins. Music by Aaron Copland

- Primer for Action (1942) premiered 92nd Street Y, New York, NY. Dancer: Erick Hawkins. Music by Ralph Gilbert

- Yankee Bluebritches (1942) premiered 92nd Street Y, New York, NY. Dancer: Erick Hawkins. Music by Hunter Johnson

- The Parting (1943) premiered 92nd Street Y, New York, NY. Dancers: Jean Erdman, Erick Hawkins. Music by Hunter Johnson

- Saturday Night (1943) premiered Sweetbriar College, Sweetbriar, Virginia. Dancers: Muriel Brenner, Erick Hawkins. Music by Gregory Tucker

- The Pilgrim's Progress (1944) premiered 92nd Street Y, New York, NY. Dancer: Erick Hawkins. Music by Wallingford Riegger

- John Brown (1947) (revived as God's Angry Man 1965 and 1985) premiered Constitution Hall, Philadelphia, PA. Dancer: Captain John Brown: Erick Hawkins. Music by Charles Mills (1914–1982)

- Stephen Acrobat (1947) premiered Ziegfeld Theatre, New York, NY. Dancer: Stuart (Gescheidt) Hodes, Erick Hawkins. Music by Robert Evett

- The Strangler (1948) premiered Palmer Auditorium, American Dance Festival at Connecticut College. Dancer: Oedipus: Eric Hawkins, Sphinx: Anne Meacham, Chorus: Joseph Wiseman. Music by Bohuslav Martinů

1950s

- Openings of the (eye) (1952) premiered 92nd Street Y, New York, NY. Dancer: Erick Hawkins. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski

- Bridegroom of the Moon (1952) premiered 92nd Street Y, New York, NY. Dancer: Erick Hawkins. Music by Wallingford Riegger

- Black House (1952) premiered, 92nd Street Y New York, NY. Dancer: Erick Hawkins. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski

- Lives of Five or Six Swords (1952) premiered 92nd Street Y, New York, NY. Dancer: Erick Hawkins. Music by Lou Harrison

- Here and Now, with watchers (1957) premiered Hunter (College) Playhouse, New York, NY. Dancer: Nancy Lang, Erick Hawkins (choreographed on Eva Raining). Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski

1960s

- 8 clear places (1960) premiered Hunter (College) Playhouse, New York, NY. Dancer: Barbara Tucker, Eric Hawkins (choreographed on Eva Raining). Music by Lucia Dlugoszewskiv

- Sudden Snake-Bird (1960) Dancers: Bird: Erick Hawkins, Snake: Kelly Holt, Kenneth LaVrack

- Early Floating (1961) premiered, Portland, OR. Dancer: Kelly Holt, Kenneth LeVrack, Ruth Ravon, Erick Hawkins. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski

- Spring Azure (1963) premiered, Hunter (College) Playhouse, New York, NY. Dancer: Kelly Holt, Albert Reid, Erick Hawkins. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski

- Cantilever (1963) Dedicated to American architect Frederick Kiesler premiered, Théâtre Recamier, Théâtre des Nations Festival, Paris, France. Dancer: Pauline DeGroot, Kelly Holt, Nancy Meehan, Erick Hawkins. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski

- To Everybody Out There (1964) premiered Palmer Auditorium, American Dance Festival at Connecticut College. Dancers: Pauline DeGroot, Kelly Holt, Nancy Meehan, Erick Hawkins, Beverly Hirschfeld, Marilyn Patton, James Tyler, Ellen Marshall. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski

- Geography of Noon (1964) (excerpts on film)[15] premiered Palmer Auditorium, American Dance Festival at Connecticut College Dancers: Eastern Tailed Blue: Nancy Meehan; Cloudless Sulpher: James Tyler (choreographed on Kelly Holt); Spring Azure: Pauline DeGroot; Variegated Fritillary: Erick Hawkins. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski

- Lords of Persia (1965) Commissioned by the American Dance Festival at Connecticut College. Dancer: Kelly Holt, Rod Rodgers, James Tyler, Erick Hawkins. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski

- Naked Leopard (1965) premiered Hunter College|Hunter (College) Playhouse, New York, NY. Dancer: Erick Hawkins. Music by Zoltán Kodály

- Dazzle on a Knife's Edge (1966) premiered Hunter College|Hunter (College) Playhouse, New York, NY. Dancer: Erick Hawkins, Beverly Hirschfeld, Kelly Hotl, Dena Madole, Barbara Roan, Rod Rogers, Penelope Shaw, James Tyler. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski

- Tightrope (1968) premiered Brooklyn Academy of Music, Brooklyn, NY. Dancers: First Everyone: Dena Madole; Second Everyone: Kelly Holt; Agnel: Robert Yohn; First Celestial: Beverly Brown; Second Celestial; Kay Gilbert; Third Celestial: Carol Ann Turoff. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski.

- Black Lake (1969) premiered Theater of the Riverside Church, New York, NY. Dancers: Beverly Brown, Kay Gilbert, Erick Hawkins, Natalie Richman, Robert Yohn, Nancy Meehan. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski.

1970s

- Of Love (1971) premiered ANTA Theatre, New York, NY. Dancers: Beverly Brown, Carol Conway, Bill Groves, Erick Hawkins, Nada Reagan, Lillo Way, Robert Yohn. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski.

- Angels of the Inmost Heaven (1971) premiered Washington D.C. Dancers: Beverly Brown, Carol Conway, Erick Hawkins, Nada Reagan, Natalie Richman, Robert Yohn. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski.

- "Classic Kite Tails" (1972) premiered Meadowbrook Festival, Detroit, MI. Dancers: Beverly Brown, Carol Conway, Erick Hawkins, Nada Reagan, Natalie Richman, Lillo Way, Robert Yohn. Music by David Diamond.

- Dawn Dazzled Door (1972) premiered Meadowbrook Festival, Detroit, MI. Dancers: Beverly Brown, Carol Conway, Erick Hawkins, Natalie Richman, Lillo Way, Robert Yohn. Music by Toru Takemitsu.

- Greek Dreams with Flute (1973) premiered Solomon Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY. Dancers: Beverly Brown, Cathy Ward, Carol Conway, Nada Regan, Natalie Richman, Robert Yohn, Erick Hawkins. Music by Claude Debussy.

- Meditations of Orpheus (1974) premiered Kennedy Center, Washington D.C. Dancers: Carol Conway, Erick Hawkins, Arlene Kennedy, Alan Lynes, Nada Reagan, Natalie Richman, Kevin Tobiason, Cathy Ward. Music by Alan Hovhaness.

- Hurrah (1975) premiered Blossom Music Center, Cleveland, OH. Dancers: Erick Hawkins, Victor Lucas, Alan Lynes, Kristin Peterson, Nada Reagan, Natalie Richman, Cathy Ward, Robert Yohn. Music by Virgil Thomson.

- Death is the Hunter (1975) premiered Carnegie Hall, New York, NY. Dancers: Erick Hawkins, Kevin Tobiason, Alan Lynes, Nada Reagan, Natalie Richman, Cathy Ward, John Wiatt, Robert Yohn. Music by Wallingford Riegger.

- Parson Weems and the Cherry Tree, etc. (1976) premiered University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA. Dancers: Erick Hawkins, Robert Yohn, Nada Reagan, John Wiatt, Natalie Richman, Cathy Ward. Music by Virgil Thomson.

- Plains Daybreak (1979) premiered Cincinnati, OH. Dancers: Erick Hawkins, Laura Pettibone, Cori Terry, Douglas Andresen, Cynthia Reynolds, Jesse Duranceau, Randy Howard, Craig Nazor, Cathy Ward. Music by Alan Hovhaness.

- Agathlon (1979) premiered in France. Dancers: Douglas Andresen, Jesse Duranceau, Randy Howard, Craig Nazor, Laura Pettibone, Cynthia Reynolds, Cori Terry, Cathy Ward. Music by Dorrance Stalvey

1980s

- Avanti (1980) (unfinished) premiered American Dance Festival at Duke University. Dancers: Douglas Andresen, Jesse Duranceau, Randy Howard, Craig Nazor, Laura Pettibone, Cynthia Reynolds, Cori Terry, Cathy Ward. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski

- Heyoka (1981) premiered Alice Tully Hall, New York, NY. Dancers: Douglas Andresen, Jesse Duranceau, Randy Howard, Craig Nazor, Helen Pelton, Laura Pettibone, Cynthia Reynolds, Cathy Ward. Music by Ross Lee Finney

- Summer Clouds People (1983) premiered Joyce Theater, New York, NY. Dancers: Douglas Andresen, Randy Howard, Helen Pelton, Laura Pettibone, Cynthia Reynolds, Daniel Tai, Cathy Ward, Mark Wisniewski. Music by Michio Mamiya

- Trickster Coyote (revival) (1983) premiered Symphony Space, New York, NY. Dancers: Randy Howard, Laura Pettibone, Cynthia Reynolds, Daniel Tai, Mark Wisniewski. Music by Henry Cowell

- The Joshua Tree (1984) premiered Joyce Theater, New York, NY. Dancers: Erick Hawkins, Randy Howard, James Reedy, Daniel Tai, Mark Wisniewski. Music by Ross Lee Finney

- God's Angry Man (1985) premiered Joyce Theater, New York, NY. Dancers: Erick Hawkins. Music by Charles Mills

- Today, with Dragon (1986) premiered Alice Tully Hall, New York, NY. Dancers: Erick Hawkins, Randy Howard, Gloria McLean, Laura Pettibone, Cynthia Reynolds, Daniel Tai, Cathy Ward, Mark Wisniewski. Music by Ge Gan-Ru

- Ahab (1986) (commissioned for Harvard University's 350th anniversary) premiered Hasty Pudding Theatre, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Dancers: Erick Hawkins, Randy Howard, Michael Moses, James Reedy, Daniel Tai, Michael Butler. Music by Ross Lee Finney

- God the Reveller (1987) premiered Kennedy Center, Washington D.C. Dancers: Katherine Duke, Randy Howard, Gloria McLean, Michael Moses, Laura Pettibone, James Reedy, Cynthis Reynolds, Sean Russo, Daniel Tai, Mariko Tanabe, Mark Wisniewski. Music by Alan Hovhaness.

- Cantilever II (1988) premiered Joyce Theater, New York, NY. Dancers: James Aarons, Brenda Connors, Katherine Duke, Randy Howard, Gloria McLean, Michael Moses, Laura Pettibone, James Reedy, Cynthia Reynolds, Sean Russo, Daniel Tai, Mariko Tanabe. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski

- New Moon (1989) premiered Joyce Theater, New York, NY. Dancers: Douglas Andresen, Renata Celichowska, Brenda Connors, Katherine Duke, Gloria McLean, Michael Moses, Laura Pettibone, Christopher Potts, Cynthia Reynolds, Frank Roth, Sean Russo, Catherine Tharin. Music by Lou Harrison

1990s

- Killer of Enemies: The Divine Hero (1991) premiered Joyce Theater, New York, NY. Dancers: Erick Hawkins, James Aarons, Douglas Andresen, Brenda Connors, Renata Celichowska, Katherine Duke, Randy Howard, Othello Jones, Gloria McLean, Joseph Mills, Michael Moses, Kathy Ortiz, Laura Pettibone, James Reedy, Cynthia Reynolds, Catherine Tharin. Music by Alan Hovhaness

- Intensities of Wind & Space (1991) premiered Joyce Theater, New York, NY. Dancers: Douglas Andresen, Othello Jones, Gloria McLean, Joseph Mills, Michael Moses, Laura Pettibone, Cynthia Reynolds, Frank Roth, Catherine Tharin. Music by Katsuhisa Hattori

- Each Time You Carry Me This Way (1993) premiered Joyce Theater, New York, NY. Dancers: Coleen McIntosh Blacklock, Othello Jones, Joseph McClintock, Joy McEwen, Gloria McLean, Tim McMinn, Joseph Mills, Kathy Ortiz, Christopher Potts, Brian Simmerson, Mariko Tanabe, Catherine Tharin. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski

- Many Thanks (1994) premiered Joyce Theater, New York, NY. Dancers: Joy McEwen, Coleen McIntosh Blacklock, Joseph Mills, Michael Moses, Kathy Ortiz, Christopher Potts, Brian Simmerson, Mariko Tanabe, Catherine Tharin. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski