| Ongoing | |

|---|---|

| Historical | |

| Proposed | |

Israel has occupied the Palestinian territories and the Golan Heights since the Six-Day War of 1967. It previously occupied the Sinai Peninsula and southern Lebanon as well. Prior to 1967, the Palestinian territories was split between the Gaza Strip controlled by Egypt and the West Bank by Jordan, while the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights are parts of Egypt and Syria, respectively. The Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories and the Golan Heights, where Israel had transferred its parts of population there and built large settlements, is the longest military occupation in modern history.

From 1967 to 1981, the four areas were administered under the Israeli Military Governorate, and after the return of the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt after the Egypt–Israel peace treaty, Israel effectively annexed the Golan Heights and East Jerusalem in 1980, and brought the rest of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip under the Israeli Civil Administration.[1]

The International Court of Justice (ICJ),[2] the UN General Assembly,[3] and the UN Security Council all regard Israel as the occupying power for the territories.[4] The ICJ in 2024 ruled that Israel's occupation was illegal and called for Israel to end its "unlawful presence … as rapidly as possible" and to make reparations to the people of the occupied territories.[5][6] UN Special Rapporteur Richard Falk called Israel's occupation "an affront to international law".[7] The Supreme Court of Israel has ruled that Israel is holding the West Bank under "belligerent occupation".[8][9] However, successive Israeli governments have preferred the term "disputed territories" in the case of the West Bank,[10][11] and Israel likewise maintains that the West Bank is disputed territory.[12]

Israel unilaterally disengaged from the Gaza Strip in 2005. The UN and a number of human rights organizations continue to consider Israel as the occupying power of the Gaza Strip due to its blockade of the territory;[13][14][15][16][17] Israel rejects this characterization.[18]

The significance of the designation of these territories as occupied territory is that certain legal obligations fall on the occupying power under international law. Under international law there are certain laws of war governing military occupation, including the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 and the Fourth Geneva Convention.[19] One of those obligations is to maintain the status quo until the signing of a peace treaty, the resolution of specific conditions outlined in a peace treaty, or the formation of a new civilian government.[20]

Israel disputes whether, and if so to what extent, it is an occupying power in relation to the Palestinian territories and as to whether Israeli settlements in these territories are in breach of Israel's obligations as an occupying power and constitute a grave breach of the Geneva Conventions and whether the settlements constitute war crimes.[21][22] In 2015, over 800,000 Israelis resided outside the 1949 Armistice Lines, constituting nearly 13% of Israel's Jewish population.[23]

| Sinai Peninsula | Southern Lebanon | Golan Heights[a] | West Bank (excluding East Jerusalem) |

East Jerusalem | Gaza Strip | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupation period | 1956–1957, 1967–1982[b] |

1948–1949,1982–2000 | 1967–present | 1967–present | 1967–present | 1956–1957, 1967–2005[c] 2023 – ongoing (portions)[d] |

| Claimed by | ||||||

| Currently administrated by | ||||||

| Israel considers it part of its territory | No | No | Yes, as part of the Northern District, by the Golan Heights Law |

De jure no, but de facto Israelis are allowed to live in settlements within Area C, as a part of the Judea and Samaria Area[h][i] | Yes, as undivided Jerusalem by the Jerusalem Law | No, but Israel has maintained control over the territory's border crossings, territorial waters, and air space since the end of the occupation in 2005 |

| Formerly part of the British Mandate | No | No | Southern half: until 1923 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Contains Israeli settlements | No; evacuated in 1982[b] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No; evacuated in 2005[j] |

Israel captured the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt in the 1967 Six-Day War. It established settlements along the Gulf of Aqaba and in the northeast portion, just below the Gaza Strip. It had plans to expand the settlement of Yamit into a city with a population of 200,000,[31] though the actual population of Yamit did not exceed 3,000.[32] The Sinai Peninsula was returned to Egypt in stages beginning in 1979 as part of the Egypt–Israel peace treaty. As required by the treaty, Israel evacuated Israeli military installations and civilian settlements prior to the establishment of "normal and friendly relations" between it and Egypt.[33] Israel dismantled eighteen settlements, two air force bases, a naval base, and other installations by 1982, including the only oil resources under Israeli control. The evacuation of the civilian population, which took place in 1982, was done forcefully in some instances, such as the evacuation of Yamit. The settlements were demolished, as it was feared that settlers might try to return to their homes after the evacuation.[citation needed] Since 1982, the Sinai Peninsula has not been regarded as occupied territory.

The Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon took place after Israel invaded Lebanon during the 1982 Lebanon War and subsequently retained its forces to support the Christian South Lebanon Army militia in Southern Lebanon. In 1982, the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) and allied Free Lebanon Army Christian militias seized large sections of Lebanon, including the capital of Beirut, amid the hostilities of the wider Lebanese Civil War. Later, Israel withdrew from parts of the occupied area between 1983 and 1985, but remained in partial control of the border region known as the South Lebanon Security Belt, initially in coordination with the self-proclaimed Free Lebanon State, which executed a limited authority over portions of southern Lebanon until 1984, and later with the South Lebanon security belt administration and its South Lebanon Army (transformed from Free Lebanon Army), until the year 2000. Israel's stated purpose for the Security Belt was to create a space separating its northern border towns from terrorists residing in Lebanon.

During the stay in the security belt, the IDF held many positions and supported the SLA. The SLA took over daily life in the security zone, initially as the official force of the Free Lebanon State and later as an allied militia. Notably, the South Lebanon Army controlled the prison in Khiam. In addition, United Nations (UN) forces and the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) were deployed to the security belt (from the end of Operation Litani in 1978).

The strip was a few kilometers wide, and consisted of about 10% of the total territory of Lebanon, which housed about 150,000 people who lived in 67 villages and towns made up of Shiites, Maronites, and Druze (most of whom lived in the town of Hasbaya). In the central zone of the Strip was the Maronite town Marjayoun, which was the capital of the security belt. Residents remaining in the security zone had many contacts with Israel, many of whom have worked there and received various services from Israel.

Before the Israeli election in May 1999, the Prime Minister of Israel, Ehud Barak, promised that within a year all Israeli forces would withdraw from Lebanon. When negotiation efforts failed between Israel and Syria—the goal of the negotiations was to bring a peace agreement between Israel and Lebanon as well, due to Syrian occupation of Lebanon until 2005—Barak led the withdrawal of the IDF to the Israeli border on 24 May 2000. No soldiers were killed or wounded during the redeployment to the internationally recognized border of Blue Line.

Israel captured the Golan Heights from Syria in the 1967 Six-Day War. A ceasefire was signed on 11 June 1967 and the Golan Heights came under Israeli military administration.[34] Syria rejected UNSC Resolution 242 of 22 November 1967, which called for the return of Israeli-occupied State territories in exchange for peaceful relations. Israel had accepted Resolution 242 in a speech to the Security Council on 1 May 1968. In March 1972, Syria "conditionally" accepted Resolution 242,[citation needed] and in May 1974, the Agreement on Disengagement between Israel and Syria was signed.

In the Yom Kippur War of 1973, Syria attempted to recapture the Golan Heights militarily, but the attempt was unsuccessful. Israel and Syria signed a ceasefire agreement in 1974 that left almost all the Heights under Israeli control, while returning a narrow demilitarized zone to Syrian control. A United Nations observation force was established in 1974 as a buffer between the sides.[35] By Syrian formal acceptance of UN Security Council Resolution 338,[36] which set out the cease-fire at the end of the Yom Kippur War, Syria also accepted Resolution 242.[37]

On 14 December 1981, Israel passed the Golan Heights Law, extending Israeli administration and law to the territory. Israel has expressly avoided using the term "annexation" to describe the change of status. However, the UN Security Council has rejected the de facto annexation in UNSC Resolution 497, which declared it as "null and void and without international legal effect",[38] and consequently continuing to regard the Golan Heights as Israeli-occupied territory. The measure has also been criticized by other countries, either as illegal or as not being helpful to the Middle East peace process.[citation needed]

Syria wants the return of the Golan Heights, while Israel has maintained a policy of "land for peace" based on Resolution 242. The first high-level public talks aimed at a resolution of the Syria–Israel conflict were held at and after the multilateral Madrid Conference of 1991. Throughout the 1990s several Israeli governments negotiated with Syria's president Hafez Al-Assad. While serious progress was made, they were unsuccessful.

In 2004, there were 34 settlements in the Golan Heights, populated by around 18,000 people.[39] Today, an estimated 20,000 Israeli settlers and 20,000 Syrians live in the territory.[35] All inhabitants are entitled to Israeli citizenship, which would entitle them to an Israeli driver's license and enable them to travel freely in Israel.[citation needed] The non-Jewish residents, who are mostly Druze, have nearly all declined to take Israeli citizenship.[35][40]

In the Golan Heights there is another area occupied by Israel, namely the Shebaa farms. Syria and Lebanon have claimed that the farms belong to Lebanon and in 2007 a UN cartographer came to the conclusion that the Shebaa farms do actually belong to Lebanon (contrary to the belief held by Israel). UN then said that Israel should relinquish the control of this area.[41]

Both of these territories were part of Mandate Palestine, and both have populations consisting primarily of Palestinians Arabs, including significant numbers of refugees who fled or were expelled from Israel and territory Israel controlled[42] after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. Today, Palestinians make up around half of Jordan's population.

Jordan occupied the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, from 1948 to 1967, annexing it in 1950 and granting Jordanian citizenship to the residents in 1954 (the annexation claims and citizenship grants were rescinded in 1988 when Jordan acknowledged the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) as the sole representative of the Palestinian people). Egypt administered the Gaza Strip from 1948 to 1967 but did not annex it or make Gazans Egyptian citizens.[43]

The West Bank was allotted to the Arab state under United Nations Partition Plan of 1947, but the West Bank was occupied by Transjordan after the 1948 war. In April 1950, Jordan annexed the West Bank,[44] but this was recognized only by the United Kingdom and Pakistan. (see 1949 Armistice Agreements, Green Line)

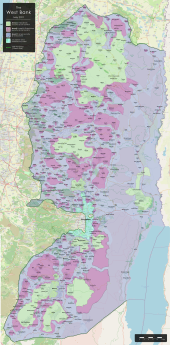

In 1967, the West Bank came under Israeli military administration. Israel retained the mukhtar (mayoral) system of government inherited from Jordan, and subsequent governments began developing infrastructure in Arab villages under its control. (see Palestinians and Israeli law, International legal issues of the conflict, Palestinian economy). As a result of "Enclave law", large portions of Israeli civil law are applied to Israeli settlements and Israeli residents in the occupied territories.[45]

Since the Israel–Palestine Liberation Organization letters of recognition of 1993, most of the Palestinian population and cities came under the jurisdiction of the Palestinian Authority, and only partial Israeli military control, although Israel has frequently redeployed its troops and reinstated full military administration in various parts of the two territories. On July 31, 1988, Jordan renounced its claims to the West Bank for the PLO.[26]

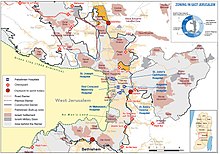

In 2000, the Israeli government started to construct the Israeli West Bank barrier, within the West Bank, separating Israel and several of its settlements, as well as a significant number of Palestinians, from the remainder of the West Bank. State of Israel cabinet approved a route to construct separation barrier whose total length will be approximately 760 km (472 mi) built mainly in the West Bank and partly along the 1949 Armistice line, or "Green Line" between Israel and Palestinian West Bank.[46] 12% of the West Bank area is on the Israel side of the barrier.[47]

In 2004, the International Court of Justice issued an advisory opinion stating that the barrier violates international law.[48] It claimed that "Israel cannot rely on a right of self-defence or on a state of necessity in order to preclude the wrongfulness of the construction of the wall".[49] However, Israel government derived its justification for constructing this barrier with Prime Minister Ehud Barak stating that it is "essential to the Palestinian nation in order to foster its national identity and independence without being dependent on the State of Israel".[50] The Israeli Supreme Court, sitting as the High Court of Justice, stated that Israel has been holding the areas of Judea and Samaria in belligerent occupation, since 1967. The court also held that the normative provisions of public international law regarding belligerent occupation are applicable. The Regulations Concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land, The Hague of 1907 and the Fourth Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War 1949 were both cited.[8]

About 500,000 Israeli settlers live in the West Bank and another 200,000 live in East Jerusalem.[51][52][53] The barrier has many effects on Palestinians including reduced freedoms, road closures, loss of land, increased difficulty in accessing medical and educational services in Israel,[54] restricted access to water sources, and economic effects. Regarding the violation of freedom of Palestinians, in a 2005 report, the United Nations stated that:[47] ...it is difficult to overstate the humanitarian impact of the Barrier. The route inside the West Bank severs communities, people's access to services, livelihoods and religious and cultural amenities. In addition, plans for the Barrier's exact route and crossing points through it are often not fully revealed until days before construction commences.[55] This has led to considerable anxiety among Palestinians about how their future lives will be impacted...The land between the Barrier and the Green Line constitutes some of the most fertile in the West Bank. It is currently the home for 49,400 West Bank Palestinians living in 38 villages and towns.[56]

On Feb 6, 2017, The Knesset passed the controversial Regulation Law, which aimed at retroactively legalizing 2,000 to 4,000 Israeli settlements in Area C.[57] On June 9, 2020, the Israeli Supreme Court struck down the law as "infringing on the property rights of Palestinian residents."[58]

In February 2023, the new Israeli government under Benjamin Netanyahu approved the legalization of nine illegal settler outposts in the West Bank.[59] Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich took charge of most of the Civil Administration, obtaining broad authority over civilian issues in the West Bank.[60][61] In June 2023, Israel shortened the procedure of approving settlement construction and gave Finance Minister Smotrich the authority to approve one of the stages, changing the system operating for the last 27 years.[62] In its first six months, construction of 13,000 housing units in settlements, almost triple the amount advanced in the whole of 2022.[63]

Jerusalem has created additional issues in relation to the question of whether or not it is occupied territory. The 1947 UN Partition Plan had contemplated that all of Jerusalem would be an international city within an international area that included Bethlehem for at least ten years, after which the residents would be allowed to conduct a referendum and the issue could be re-examined by the Trusteeship Council.

However, after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Jordan captured East Jerusalem and the Old City, and Israel captured and annexed the western part of Jerusalem [citation needed]. Jordan bilaterally annexed East Jerusalem along with the rest of the West Bank in 1950 as a temporary trustee [64] at the request of a Palestinian delegation,[65] and although the annexation was recognized by only two countries, it was not condemned by the UNSC. The British did not recognize the territory as sovereign to Jordan.[66] Israel captured East Jerusalem from Jordan in the 1967 Six-Day War. On June 27, Israel extended its laws, jurisdiction, and administration to East Jerusalem and several nearby towns and villages, and incorporated the area into the Jerusalem Municipality. In 1980, the Knesset passed the Jerusalem Law, which was declared a Basic Law, which declared Jerusalem to be the "complete and united" capital of Israel. However, United Nations Security Council Resolution 478 declared this action to be "null and void", and that it "must be rescinded forthwith". The international community does not recognize Israeli sovereignty over East Jerusalem and considers it an occupied territory.[67]

UN Security Council Resolution 478 also called upon countries which held their diplomatic delegations to Israel in Jerusalem, to move them outside the city. Most nations with embassies in Jerusalem complied, and relocated their embassies to Tel Aviv or other Israeli cities prior to the adoption of Resolution 478. Following the withdrawals of Costa Rica and El Salvador in August 2006, no country maintained its embassy in Jerusalem until 2018, although Bolivia and Paraguay once had theirs in nearby Mevaseret Zion.[68][69] The United States Congress passed the Jerusalem Embassy Act in 1995, stating that "Jerusalem should be recognized as the capital of the State of Israel; and the United States Embassy in Israel should be established in Jerusalem no later than May 31, 1999." As a result of the Embassy Act, official U.S. documents and web sites refer to Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. Until May 2018, the law had never been implemented, because successive U.S. Presidents Clinton, Bush, and Obama exercised the law's presidential waiver, citing national security interests. On 14 May 2018, the U.S. opened its Embassy in Jerusalem.[70]

East Jerusalem residents are increasingly becoming integrated into Israeli society, in terms of education, citizenship, national service and in other aspects.[71][72] Recent surveys show that, if given the option of having East Jerusalem transferred today from Israeli rule to the Palestinian National Authority, most East Jerusalem Palestinians would oppose the proposal.[71][73][74] According to Middle East expert David Pollock, in the hypothesis that a final agreement was reached between Israel and the Palestinians with the establishment of a two-state solution, 48% of East Jerusalem Arabs would prefer being citizens of Israel, while 42% of them would prefer the State of Palestine. 9% would prefer Jordanian citizenship.[75]

In May 2021, clashes occurred between Palestinians and Israeli police over further anticipated Palestinian evictions in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem.[76]

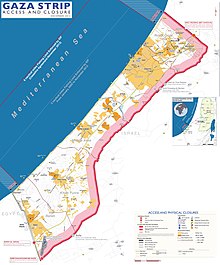

The Gaza Strip was allotted to the Arab state envisioned by the United Nations Partition Plan of 1947, but no Arab state formed as a result of the 1947 partition plan. As a result of the 1949 Armistice Agreements, the Gaza Strip became occupied by Egypt.

Between 1948 and 1967, the Gaza Strip was under Egyptian military administration, being officially under the jurisdiction of the All-Palestine Government until in 1959 it was merged into the United Arab Republic, de facto becoming under direct Egyptian military governorship.

Between 1967 and 1993, the Gaza Strip was under Israeli military administration. In March 1979, Egypt renounced all claims to the Gaza Strip in the Egypt–Israel peace treaty.

Since the Israel–Palestine Liberation Organization letters of recognition of 1993, the Gaza Strip came under the jurisdiction of the Palestinian Authority.

A July 2004 opinion of the International Court of Justice treated Gaza as a part of the Occupied Palestinian Territory.[77]

In February 2005, the Israeli government voted to implement a unilateral disengagement plan from the Gaza Strip. The plan began to be implemented on 15 August 2005, and was completed on 12 September 2005. Under the plan, all Israeli settlements in the Gaza Strip (and four in the West Bank) and the joint Israeli-Palestinian Erez Industrial Zone were dismantled with the removal of all 9,000 Israeli settlers (most of them in the Gush Katif settlement area in the Strip's southwest) and military bases. Some settlers resisted the order, and were forcibly removed by the IDF. On 12 September 2005 the Israeli cabinet formally declared an end to Israeli military occupation of the Gaza Strip. To avoid allegations that it was still in occupation of any part of the Gaza Strip, Israel also withdrew from the Philadelphi Route, which is a narrow strip adjacent to the Strip's border with Egypt, after Egypt's agreement to secure its side of the border. Under the Oslo Accords the Philadelphi Route was to remain under Israeli control to prevent the smuggling of materials (such as ammunition) and people across the border with Egypt. With Egypt agreeing to patrol its side of the border, it was hoped that the objective would be achieved. However, Israel maintained its control over the crossings in and out of Gaza. The Rafah crossing between Egypt and Gaza was monitored by the Israeli army through special surveillance cameras. Official documents such as passports, I.D. cards, export and import papers, and many others had to be approved by the Israeli army.[citation needed]

The Israeli position is that it no longer occupies Gaza, as Israel does not exercise effective control or authority over any land or institutions inside the Gaza Strip.[78][79] Foreign Affairs Minister of Israel Tzipi Livni stated in January, 2008: "Israel got out of Gaza. It dismantled its settlements there. No Israeli soldiers were left there after the disengagement."[80] Israel also notes that Gaza does not belong to any sovereign state.[79]

Immediately after Israel withdrew in 2005, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas stated, "the legal status of the areas slated for evacuation has not changed."[78] Human Rights Watch also contested that this ended the occupation.[81][82][83] The United Nations, Human Rights Watch and many other international bodies and NGOs continues to consider Israel to be the occupying power of the Gaza Strip as Israel controls the Gaza Strip's airspace and territorial waters as well as the movement of people or goods in or out of Gaza by air or sea.[14][15][16]

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs maintains an office on "Occupied Palestinian Territory", which concerns itself with the Gaza Strip.[84] In his statement on the 2008–2009 Israel–Gaza conflict Richard Falk, United Nations Special Rapporteur on "the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories" wrote that international humanitarian law applied to Israel "in regard to the obligations of an Occupying Power and in the requirements of the laws of war."[85] In a 2009 interview on Democracy Now Christopher Gunness, spokesperson for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) contends that Israel is an occupying power. However, Meagan Buren, senior adviser to the Israel Project, a pro-Israel media group, contests that characterization.[86]

In 2007, after Hamas defeated Fatah in the Battle of Gaza (2007) and took control over the Gaza Strip, Israel imposed a blockade on Gaza. Palestinian rocket attacks and Israeli raids, such as Operation Hot Winter continued into 2008. A six month ceasefire was agreed in June 2008, but it was broken several times by both Israel and Hamas. As it reached its expiry, Hamas announced that they were unwilling to renew the ceasefire without improving the terms.[87] At the end of December 2008 Israeli forces began Operation Cast Lead, launching the Gaza War that left an estimated 1,166–1,417 Palestinians and 13 Israelis dead.[88][89][90]

In January 2012, the spokesperson for the UN Secretary General stated that under resolutions of the Security Council and the General Assembly, the UN still regards Gaza to be a part of the Occupied Palestinian Territory.[13]

On 7 October 2023, Hamas launched a major attack on Israel from the Gaza Strip.[91] On 9 October 2023, following the beginning of the Israel–Hamas war and attacks in Israel by Hamas militants, Israel imposed a "total blockade" of the Gaza Strip.[92] The total blockade of Gaza was announced by Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant, who declared: "There will be no electricity, no food, no fuel, everything is closed."[93]

Al Haq, an independent Palestinian human rights organization based in Ramallah in the West Bank and an affiliate of the International Commission of Jurists, has asserted that "As noted in Article 27 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 'a party may not invoke the provisions of its internal law as justification for its failure to perform a treaty'. As such, Israeli reliance on local law does not justify its violations of its international legal obligations".[94] Further, the Palestinian mission to the U.N. has argued that:[95]

it is of no relevance whether a State has a monist or a dualist approach to the incorporation of international law into domestic law. A position dependent upon such considerations contradicts Article 18 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties of 1969 which states that: "a state is obliged to refrain from acts which would defeat the object and purposes of a treaty when it has undertaken an act expressing its consent thereto." The Treaty, which is substantially a codification of customary international law, also provides that a State "may not invoke the provisions of its internal law as justification for its failure to perform a treaty" (Art. 27).

The Israeli government maintains that according to international law the West Bank status is that of disputed territories.[96][97]

The question is important given if the status of "occupied territories" has a bearing on the legal duties and rights of Israel toward those.[98] Hence it has been discussed in various forums including the UN.

Israel justifies its control over the territories by citing Jewish presence beginning in biblical times, Jordan's prior illegal occupation and initiation of the 1967 war, and security needs due to its small borders and hostile neighbors. Israel states that the territories' final status should be decided through negotiations.[99]

In two cases decided shortly after independence, in the Shimshon and Stampfer cases, the Supreme Court of Israel held that the fundamental rules of international law accepted as binding by all "civilized" nations were incorporated in the domestic legal system of Israel. The Nuremberg Military Tribunal determined that the articles annexed to the Hague IV Convention of 1907 were customary law that had been recognized by all civilized nations.[100] In the past, the Supreme Court has argued that the Geneva Convention insofar it is not supported by domestic legislation "does not bind this Court, its enforcement being a matter for the states which are parties to the Convention". They ruled that "Conventional international law does not become part of Israeli law through automatic incorporation, but only if it is adopted or combined with Israeli law by enactment of primary or subsidiary legislation from which it derives its force". However, in the same decision the Court ruled that the Fourth Hague Convention rules governing belligerent occupation did apply, since those were recognized as customary international law.[101]

The Israeli High Court of Justice determined in the 1979 Elon Moreh case that the area in question was under occupation and that accordingly only the military commander of the area may requisition land according to Article 52 of the Regulations annexed to the Hague IV Convention. Military necessity had been an after-thought in planning portions of the Elon Moreh settlement. That situation did not fulfill the precise strictures laid down in the articles of the Hague Convention, so the Court ruled the requisition order had been invalid and illegal.[102] In recent decades, the government of Israel has argued before the Supreme Court of Israel that its authority in the territories is based on the international law of "belligerent occupation", in particular the Hague Conventions. The court has confirmed this interpretation many times, for example in its 2004 and 2005 rulings on the separation fence.[103][104]

In its June 2005 ruling upholding the constitutionality of the Gaza disengagement, the Court determined that "Judea and Samaria" [West Bank] and the Gaza area are lands seized during warfare, and are not part of Israel:

The Judea and Samaria Area is held by the State of Israel in belligerent occupation. The long arm of the state in the area is the military commander. He is not the sovereign in the territory held in belligerent occupation (see The Beit Sourik Case, at p. 832). His power is granted him by public international law regarding belligerent occupation. The legal meaning of this view is twofold: first, Israeli law does not apply in these areas. They have not been "annexed" to Israel. Second, the legal regime which applies in these areas is determined by public international law regarding belligerent occupation (see HCJ 1661/05 The Gaza Coast Regional Council v. The Knesset et al. (yet unpublished, paragraph 3 of the opinion of the Court; hereinafter – The Gaza Coast Regional Council Case). In the center of this public international law stand the Regulations Concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land, The Hague, 18 October 1907 (hereinafter – The Hague Regulations). These regulations are a reflection of customary international law. The law of belligerent occupation is also laid out in IV Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War 1949 (hereinafter – the Fourth Geneva Convention).[105][106]

Soon after the 1967 war, Israel issued a military order stating that the Geneva Conventions applied to the recently occupied territories,[107] but this order was rescinded a few months later.[108] For a number of years, Israel argued on various grounds that the Geneva Conventions do not apply. One is the Missing Reversioner theory[109] which argued that the Geneva Conventions apply only to the sovereign territory of a High Contracting Party, and therefore do not apply since Jordan never exercised sovereignty over the region.[101] However, that interpretation is not shared by the international community.[110] The application of Geneva Convention to Occupied Palestinian Territories was further upheld by International Court of Justice, UN General Assembly, UN Security Council and the Israeli Supreme Court.[110]

In the cases before the Israeli High Court of Justice the government has agreed that the military commander's authority is anchored in the Fourth Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, and that the humanitarian rules of the Fourth Geneva Convention apply.[111] The Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs says that the Supreme Court of Israel has ruled that the Fourth Geneva Convention and certain parts of Additional Protocol I reflect customary international law that is applicable in the occupied territories.[112]

Former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Meir Shamgar, taking a different approach, wrote in the 1970s that there is no de jure applicability of the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention regarding occupied territories to the case of the West Bank and Gaza Strip since the Convention "is based on the assumption that there had been a sovereign who was ousted and that he had been a legitimate sovereign."[113] Israeli diplomat, Dore Gold, has stated that the language of "occupation" has allowed Palestinian spokesmen to obfuscate this history. By repeatedly pointing to "occupation," they manage to reverse the causality of the conflict, especially in front of Western audiences. Thus, the current territorial dispute is allegedly the result of an Israeli decision "to occupy," rather than a result of a war imposed on Israel by a coalition of Arab states in 1967.[113]

Gershom Gorenberg, disputing these views, has written that the Israeli government knew at the outset that it was violating the Geneva Convention by creating civilian settlements in the territories under IDF administration. He explained that as the legal counsel of the Foreign Ministry, Theodor Meron was the Israeli government's expert on international law. On September 16, 1967, Meron wrote a top secret memo to Mr. Adi Yafeh, Political Secretary of the Prime Minister regarding "Settlement in the Administered Territories" which said "My conclusion is that civilian settlement in the Administered territories contravenes the explicit provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention."[114] Moshe Dayan authored a secret memo in 1968 proposing massive settlement in the territories which said "Settling Israelis in administered territory, as is known, contravenes international conventions, but there is nothing essentially new about that."[115]

Various Israeli Cabinets have made political statements and many of Israel's citizens and supporters dispute that the territories are occupied and claim that use of the term "occupied" in relation to Israel's control of the areas has no basis in international law or history, and that it prejudges the outcome of any future or ongoing negotiations. They argue it is more accurate to refer to the territories as "disputed" rather than "occupied" although they agree to apply the humanitarian provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention pending resolution of the dispute. Yoram Dinstein has dismissed the position that they are not occupied as being "based on dubious legal grounds, considering that the Fourth Geneva Convention does not make its applicability conditional on recognition of [sovereign] titles".[116] Many Israeli government websites do refer to the areas as being "occupied territories".[117] According to the BBC, "Israel argues that the international conventions relating to occupied land do not apply to the Palestinian territories because they were not under the legitimate sovereignty of any state in the first place."[118]

In the Report on the Legal Status of Building in Judea and Samaria, usually referred to as Levy Report, published in July 2012, a three-member committee headed by former Israeli Supreme Court justice Edmund Levy which was appointed by Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu comes to the conclusion that Israel's presence in the West Bank is not an occupation in the legal sense,[119] and that the Israeli settlements in those territories do not contravene international law.[120] The report has met with both approval and harsh criticism in Israel and outside. As of July 2013, the report was not brought before the Israeli cabinet or any parliamentary or governmental body which would have the power to approve it.

According to the views of most adherents of Religious Zionism and to certain streams of Orthodox Judaism, there are no, and cannot be, "occupied territories" because all of the Land of Israel (Hebrew: אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל ʼÉreṣ Yiśrāʼēl, Eretz Yisrael) belongs to the Jews, also known as the Children of Israel, since the times of Biblical antiquity based on various Hebrew Bible passages.[citation needed]

The Jewish religious belief that the area is a God-given inheritance of the Jewish people is based on the Torah, especially the books of Genesis and Exodus, as well as the Prophets. According to the Book of Genesis, the land was promised by God to the descendants of Abraham through his son Isaac and to the Israelites, descendants of Jacob, Abraham's grandson. A literal reading of the text suggests that the land promise is (or was at one time) one of the Biblical covenants between God and the Israelites, as the following verses show.[citation needed]

The definition of the limits of this territory varies between biblical passages, some of the main ones being:

The boundaries of the Land of Israel are different from the borders of historical Israelite kingdoms. The Bar Kokhba state, the Herodian Kingdom, the Hasmonean Kingdom, and possibly the United Kingdom of Israel and Judah[121] ruled lands with similar but not identical boundaries. The current State of Israel also has similar but not identical boundaries.

A small sect of Haredi Jews, the Neturei Karta opposes Zionism and calls for a peaceful dismantling of the State of Israel, in the belief that Jews are forbidden to have their own state until the coming of the Messiah.[122][123]

The official term used by the United Nations Security Council to describe Israeli-occupied territories is "the Arab territories occupied since 1967, including Jerusalem", which is used, for example, in Resolutions 446 (1979) Archived 2015-05-17 at the Wayback Machine, 452 (1979) Archived 2015-04-04 at the Wayback Machine, 465 (1980) and 484. A conference of the parties to the Fourth Geneva Convention,[124] and the International Committee of the Red Cross,[125] have also resolved that these territories are occupied and that the Fourth Geneva Convention provisions regarding occupied territories apply.

Israel's annexation of East Jerusalem in 1980 (see Jerusalem Law) has not been recognized by any other country,[126] and the annexation of the Golan Heights in 1981 (see Golan Heights Law) has been recognized only by the United States. United Nations Security Council Resolution 478 declared the annexation of East Jerusalem "null and void" and required that it be rescinded. United Nations Security Council Resolution 497 also declared the annexation of the Golan "null and void". Following withdrawal by Israel from the Sinai Peninsula in 1982, as part of the 1979 Egypt–Israel peace treaty, the Sinai ceased to be considered occupied territory. While the Palestinian Authority, the EU,[127] the International Court of Justice,[2] the UN General Assembly[3] and the UN Security Council[128] consider East Jerusalem to be part of the West Bank and occupied by Israel; Israel considers all of Jerusalem to be its capital and sovereign territory.[129]

The international community has formally entrusted the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) with the role of guardian of international humanitarian law. That includes a watchdog function by which it takes direct action to encourage parties to armed conflict to comply with international humanitarian law.[130] The head of the International Red Cross delegation to Israel and the Occupied Territories stated that the establishment of Israeli settlements in the occupied territories is a grave breach of the Geneva Conventions that constitute war crime.[131]

In 1986, the International Court of Justice ruled that portions of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 merely declare existing customary international law.[132] In 1993, the UN Security Council adopted a binding Chapter VII resolution establishing an International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. The resolution approved a Statute which said that the problem of adherence of some but not all States to the Geneva Conventions does not arise, since beyond any doubt the Convention is declarative of customary international law.[133] The subsequent interpretation of the International Court of Justice does not support Israel's view on the applicability of the Geneva Conventions.[134]

In July 2004, the International Court of Justice delivered an Advisory Opinion on the 'Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory'. The Court observed that under customary international law as reflected in Article 42 of the Regulations annexed to the Hague IV Convention, territory is considered occupied when it is actually placed under the authority of the hostile army, and the occupation extends only to the territory where such authority has been established and can be exercised. Israel raised a number of exceptions and objections,[135] but the Court found them unpersuasive. The Court ruled that territories had been occupied by the Israeli armed forces in 1967, during the conflict between Israel and Jordan, and that subsequent events in those territories, had done nothing to alter the situation.

Multiple United Nations General Assembly resolutions have described the continuing occupation of Palestine as illegal.[136] Michael Lynk, the United Nations special rapporteur on human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, in his 2017 report to the UN General Assembly has opined that the occupation itself has become illegal and has recommended that a UN study be commissioned to determine this and to consider asking the International Court of Justice for an advisory opinion.[137] The general thrust of international law scholarship addressing this question has concluded that, regardless of whether it was initially legal, the occupation has become illegal over time. Reasons cited for its illegality include the violation of the prohibition on the acquisition of territory through force, that the occupation violates the Palestinian right to self-determination, that the occupation itself is an illegal regime "of alien subjugation, domination and exploitation", or some combination of these factors.[138]

The establishment of Israeli settlements is held to constitute a transfer of Israel's civilian population into the occupied territories and as such is illegal under the Fourth Geneva Convention.[139][140][141] This is disputed by other legal experts who argue with this interpretation of the law.[142]

In 2000, the editors of the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Palestine Yearbook of International Law (1998–1999) said "the "transfer, directly or indirectly, by the Occupying Power of parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies, or the deportation or transfer of all or parts of the population of the occupied territory within or outside this territory" amounts to a war crime. They hold that this is obviously applicable to Israeli settlement activities in the Occupied Arab Territories."[143]

In 2004 the International Court of Justice, in an advisory, non-binding[144] opinion, noted that the Security Council had described Israel's policy and practices of settling parts of its population and new immigrants in the occupied territories as a "flagrant violation" of the Fourth Geneva Convention. The Court also concluded that the Israeli settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (including East Jerusalem) have been established "in breach of international law" and that all the States parties to the Geneva Convention are under an obligation to ensure compliance by Israel with international law as embodied in the Convention.[134]

In May 2012 the 27 ministers of foreign affairs of the European Union published a report strongly denouncing policies of the State of Israel in the West Bank and finding that settlements in the West Bank are illegal: "settlements remain illegal under international law, irrespective of recent decisions by the government of Israel. The EU reiterates that it will not recognize any changes to the pre-1967 borders including with regard to Jerusalem, other than those agreed by the parties."[145] The report by all EU foreign ministers also criticized the Israeli government's failure to dismantle settler outposts illegal even under domestic Israeli law."[145]

Israel denies that the Israeli settlements are in breach of any international laws.[146] The Israeli Supreme Court has yet to rule decisively on settlement legality under the Geneva Convention.[147]

The United Nations Human Rights Commission decided in March 2012 to establish a panel charged with investigating "the implications of the Israeli settlements on the civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights of the Palestinian people throughout the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem."[148] In reaction the government of Israel ceased cooperating with the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights and boycotted the UN Human Rights Commission. The U.S. government acceded to the Israeli government demand to attempt to thwart the formation of such a panel.[148]

On January 31, 2012, the United Nations independent "International Fact-Finding Mission on Israeli Settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territory" filed a report stating that Israeli settlement led to a multitude of violations of Palestinian human rights and that if Israel did not stop all settlement activity immediately and begin withdrawing all settlers from the West Bank, it potentially might face a case at the International Criminal Court. It said that Israel was in violation of article 49 of the fourth Geneva convention forbidding transferring civilians of the occupying nation into occupied territory. It held that the settlements are "leading to a creeping annexation that prevents the establishment of a contiguous and viable Palestinian state and undermines the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination." After Palestine's admission to the United Nations as a non-member state in September 2012, it potentially may have its complaint heard by the International Court. Israel's foreign ministry replied to the report saying that "Counterproductive measures – such as the report before us – will only hamper efforts to find a sustainable solution to the Israel-Palestinian conflict. The human rights council has sadly distinguished itself by its systematically one-sided and biased approach towards Israel."[149][150][151]

Following a decision by European Union (EU) foreign ministers in December 2012 stating that "all agreements between the state of Israel and the EU must unequivocally and explicitly indicate their inapplicability to the territories occupied by Israel in 1967", the European Commission issued guidelines for the 2014 to 2020 financial framework covering all areas of co-operation between the EU and Israel, including economics, science, culture, sports and academia but excluding trade on 30 June 2013. According to the directive all future agreements between the EU and Israel must explicitly exclude Jewish settlements and Israeli institutions and bodies situated across the pre-1967 Green Line – including the Golan Heights, the West Bank and East Jerusalem.[152] EU grants, funding, prizes or scholarships will only be granted if a settlement exclusion clause is included, forcing the Israeli government to concede in writing that settlements in the occupied territories are outside the state of Israel to secure agreements with the EU.[153]

In a statement, the EU said that

the guidelines are...in conformity with the EU's longstanding position that Israeli settlements are illegal under international law and with the non-recognition by the EU of Israel's sovereignty over the occupied territories, irrespective of their legal status under domestic Israeli law. At the moment Israeli entities enjoy financial support and cooperation with the EU and these guidelines are designed to ensure that this remains the case. At the same time concern has been expressed in Europe that Israeli entities in the occupied territories could benefit from EU support. The purpose of these guidelines is to make a distinction between the State of Israel and the occupied territories when it comes to EU support.[154]

The guidelines do not apply to any Palestinian body in the West Bank or East Jerusalem, and they do not affect agreements between the EU and the PLO or the Palestinian Authority, nor do they apply to Israeli government ministries or national agencies, to private individuals, to human rights organizations operating in the occupied territories, or to NGOs working toward promoting peace which operate in the occupied territories.[155][156]

The move was described as an "earthquake" by an Israeli official who wished to remain anonymous,[153] and prompted harsh criticism by prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu who said in a broadcast statement: "As prime minister of Israel, I will not allow the hundreds of thousands of Israelis who live in the West Bank, Golan Heights and our united capital Jerusalem to be harmed. We will not accept any external diktats about our borders. This matter will only be settled in direct negotiations between the parties." Israel is also concerned that the same policy could extend to settlement produce and goods exported to European markets, as some EU member states are pressing for an EU-wide policy of labelling produce and goods originating in Jewish settlements to allow consumers to make informed choices.[152] A special ministerial panel led by prime minister Netanyahu, decided to approach the EU and demand several key amendments in the guidelines before entering any new projects with the Europeans. A spokesperson for the EU confirmed that further talks would take place between Israel and the EU, stating: "We stand ready to organise discussions during which such clarifications can be provided and look forward to continued successful EU-Israel cooperation, including in the area of scientific cooperation."[157]

Palestinians and their supporters hailed the EU directive as a significant political and economic sanction against settlements. Hanan Ashrawi welcomed the guidelines, saying: "The EU has moved from the level of statements, declarations and denunciations to effective policy decisions and concrete steps, which constitute a qualitative shift that will have a positive impact on the chances of peace."[152]

The International Court of Justice delivered a landmark advisory opinion in July 2024 that Israel's occupation of West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip was illegal, and that this "unlawful presence" should be ended "as rapidly as possible".[5][158] The court found that Israel's occupation was illegal due to "sustained abuse by Israel of its position as an occupying power through its annexation and assertion of permanent control over occupied Palestinian territory, and its continued frustration of the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination".[159][160] The court also stated that Israel should "make reparations for the damage caused to all the people" of such lands, and that Israel also had "an obligation to cease immediately all new settlement activities and to evacuate all settlers" from the West Bank and East Jerusalem.[6][161]

'If the Levy Committee is pushing the government to determine that Israel's presence in the West Bank does not violate international law, Israel is in a dangerous position facing the rest of the world,' said Sasson this morning to Haaretz. ... 'For 45 years, different compositions of the High Court of Justice stated again and again that international law applies to the West Bank, which is clearly opposed to Levy's findings. This is a colossal turnaround, which I do not think is within his authority. He can tell the government that he recommends changing legal status, and that's all,' said Sasson.

0876091052.

Because of the continuing controls Israel exercises over the lives and welfare of Gaza's inhabitants, Israel remains an occupying power under international humanitarian law, despite withdrawing its military forces and settlements from the territory in 2005.

annexations, expulsions and the creation of settlements are specifically prohibited by international law. The Fourth Geneva Convention, in Article 47, proscribes the annexation of occupied territory, and the United Nations has repeatedly condemned Israel's precipitous annexation of East Jerusalem and a wide belt of surrounding suburbs, villages and towns. Article 49 of the same convention prohibits the forcible transfer or deportation of residents from an occupied area, regardless of motive. And yet thousands of Palestinians have been expelled (see Lesch, 1979: 113–130, for a partial list of the "officially deported" ones) while many more have been, through measures to be described below, "pressured" to leave. The same Article expressly forbids the transfer by an occupying power of any of its civilian population into occupied areas. And yet, at most recent count, over 90,000 Israeli Jews have been officially "settled" within the illegally annexed Jerusalem district, and more than 30,000 others have been "settled" in some 100 nahals (military forts), villages and even towns that the Israeli government has authorized, planned, financed and built in unannexed zones beyond the 1949 cease-fire line that Israelis refer to not as a border, but euphemistically as a "green line."

Article 49 has been interpreted as prohibiting both forced deportations of Palestinians and population transfers of the sort associated with the establishment and continuous expansion of Israeli settlements

The settlements program is quite simply contrary to international law. However, it is now so far advanced, and so plainly in violation of the Geneva Convention, that it actually creates a powerful reason for Israel's continuing refusal to accept that the Convention is applicable in the occupied territories on a de jure basis

Are Israeli settlements legal?