| Mutiny on the Bounty | |

|---|---|

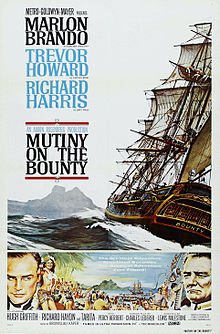

Original film poster by Reynold Brown | |

| Directed by | Lewis Milestone |

| Screenplay by | Charles Lederer |

| Based on | Mutiny on the Bounty 1932 novel by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall |

| Produced by | Aaron Rosenberg |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert L. Surtees |

| Edited by | John McSweeney Jr. |

| Music by | Bronisław Kaper |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 178 minutes (UK: 185 minutes) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $19 million or $17 million[1] |

| Box office | $13.6 million[2] |

Mutiny on the Bounty is a 1962 American Technicolor epic historical drama film released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, directed by Lewis Milestone and starring Marlon Brando, Trevor Howard, and Richard Harris. The screenplay was written by Charles Lederer (with uncredited input from Eric Ambler, William L. Driscoll, Borden Chase, John Gay, and Ben Hecht),[3] based on the novel Mutiny on the Bounty by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall. Bronisław Kaper composed the score.

The film tells a heavily fictionalized story of the real-life mutiny led by Fletcher Christian against William Bligh, captain of HMAV Bounty, in 1789. It is the second American film produced by MGM to be based on the novel, the first being Mutiny on the Bounty (1935).

Mutiny on the Bounty was the first motion picture filmed in the Ultra Panavision 70 widescreen process. It was partly shot on location in the South Pacific. Panned by critics, the film was a box office flop, losing more than $6 million (equivalent to $60 million in 2023).

In the year 1787, the Bounty sets sail from Britain for Tahiti under the command of Captain William Bligh. His mission is to collect a shipload of breadfruit saplings and transport them to Jamaica. The government hopes the plants will thrive and provide a cheap source of food for the slaves.

The voyage gets off to a difficult start with the discovery that some cheese is missing. Seaman John Mills accuses Bligh, the true pilferer, and Bligh has Mills brutally flogged for showing contempt to his superior officer, to the disgust of his second-in-command, First Lieutenant Fletcher Christian. Bligh tries to reach Tahiti sooner by attempting the shorter westbound route around Cape Horn. The strategy fails and the Bounty backtracks eastward, costing the mission much precious time. Singlemindedly, Bligh makes up the lost time by pushing the crew harder and cutting their rations.

When the Bounty reaches her destination, the crew revels in the easygoing life of the tropical paradise – and in the free-love philosophies of the Tahitian women. Christian himself is smitten with Maimiti, daughter of the Tahitian king. Bligh's agitation is further fueled by the fact that the dormancy period of the breadfruit means more months of delay until the plants can be potted. As departure day nears, three men, including seaman Mills, attempt to desert but are caught by Christian and clapped in irons by Bligh.

On the voyage to Jamaica, Bligh attempts to bring back twice the number of breadfruit plants to atone his tardiness, and reduce the water rations of the crew to water the extra plants. One member of the crew falls from the rigging to his death while attempting to retrieve the drinking ladle, as the other assaults Bligh and is fatally keelhauled to his death. Mills taunts Christian after each death, trying to egg him on to challenge Bligh. When a crewman becomes gravely ill from drinking seawater, Christian attempts to give him fresh water, in violation of the Captain's orders. Bligh strikes Christian when he ignores his second order to stop. In response, Christian strikes Bligh. Bligh informs Christian that he will hang for his actions when they reach port.

With nothing left to lose, Christian takes command of the ship and sets Bligh and the loyalist members of the crew adrift in the longboat with a compass and meager rations, telling them to make for the island of Tofua. Bligh decides to avoid Tofua and the rest of the islands because the locals there practiced cannibalism, and instead to cross much of the Pacific westward in order to reach the nearest port. He returns to Britain with remarkable speed.

The court martial exonerates Bligh of any misdeeds and recommends an expedition to arrest the mutineers and put them on trial, but it also comes to the conclusion that the appointment of Bligh as captain of the Bounty was a mistake. In the meantime, Christian sails back to Tahiti to pick up supplies, Maimiti and the girlfriends of the crew. They sailed to several islands until they reached Pitcairn Island, which is marked incorrectly on the charts. However, once on Pitcairn, Christian decides that it is their duty to return to Britain and testify to Bligh's wrongdoing, and he asks his men to sail with him. To prevent this possibility, Mills and the rest set the Bounty on fire and Christian is fatally burned after retrieving the ship's sextant. Christian dies on Maimiti's arms as the Bounty burns and sinks.

Following the success of 1935's Mutiny on the Bounty, director Frank Lloyd announced plans in 1940 to make a sequel that focused on Captain Bligh in later life, to star Spencer Tracy or Charles Laughton. No film resulted. In 1945 Casey Wilson wrote a script for Christian of the Bounty, which was to star Clark Gable as Fletcher Christian and focus on Christian's life on Pitcairn Island.[4] This was never filmed. In the 1950s, MGM remade a number of their earlier successes in color and widescreen formats, including Scaramouche and The Prisoner of Zenda. They decided to remake Mutiny on the Bounty, and in 1958 the studio announced that Aaron Rosenberg would produce the film. Marlon Brando was mentioned as a possible star.[5]

Eric Ambler was signed to write a script at $5,000 per week. It was supposed to combine material from the Nordhoff and Hall novels Mutiny on the Bounty and Pitcairn Island. MGM also owned the rights to a third book, Men Against the Sea, which dealt with Bligh's boat voyage after the mutiny.[4] In 1959, Paramount announced that it would make a rival Bounty film, to be written and directed by James Clavell and called The Mutineers. It would focus on the fate of the Mutineers on Pitcairn Island.[4] However, this project did not proceed.

Marlon Brando eventually signed with MGM, at a fee of $500,000 plus 10% of the profits. Carol Reed was hired to direct. In order to take full advantage of Technicolor and the widescreen format (shooting in MGM Camera 65), the production was to be filmed on location in Tahiti, with cinematographer Robert Surtees. The film was set to begin shooting on October 15, 1960. It was nicknamed "MGM's Ben Hur of 1961."[6] Brando wrote in his memoirs that he was offered the lead in Lawrence of Arabia around the same time but chose the Bounty because he preferred to go to Tahiti, a place that had long fascinated him, rather than film six months in the desert. "Lean was a very good director, but he took so long to make a movie that I would have dried up in the desert like a puddle of water", wrote Brando.[7]

Rosenberg said the film would focus more on the fate of the crew after the mutiny, with Captain Bligh only in a minor role and the mutiny dealt with in flashback. "It was Brando's idea", said Rosenberg. "And he was right. It has always been fascinating to wonder what happened to the mutineers afterwards."[8] "The mood after the mutiny must be one of hope", said Reed. "The men hope to live a different sort of life, a life without suffering, without brutality. They hope for a life without sick ambitions, without the pettiness of personal success. They dream of a new life where nobody is trying to outdo the next person."[8]

Ambler says his brief was to make Fletcher Christian's part as interesting as Bligh's.[9] MGM executives were unhappy with Ambler's script, although the writer estimated he did 14 drafts.[10] John Gay was signed to write a version in July 1960. Eventually, William Driscoll, Borden Chase (writing in August 1960), Howard Clewes and Charles Lederer wrote all the scripts.[11] According to one report, Ambler did the first third of the film, about the journey, Driscoll did the second, about life on Tahiti, and Chase did the third, about the mutiny and afterwards. Gay wrote the narration. Lederer was included before filming was to begin.[12]

In July 1960, Peter Finch signed to play Bligh.[13] However, by August the role had gone to Trevor Howard.[14] Brando personally selected a local Tahitian, Tarita, to play his love interest. They married in 1962 and divorced in 1972.[15]

A working replica of the Bounty was built in Nova Scotia at a cost of $750,000 and was sailed to Tahiti. It took nine months to make rather than the scheduled six and arrived after filming had started.[16] Shooting was supposed to begin in October 1960; however, delays in the scripting and construction of the ship meant it did not begin until November. More than 150 cast and crew arrived in Tahiti, and MGM took over 200 hotel rooms.[15]

Shooting began on November 28. Filming was difficult, in part because the script was being rewritten and Brando was reportedly ad-libbing much of his part. Costs were also high due to the remote location.[17] Despite the ongoing changes to the script and the production's financial and logistical problems, Brando later wrote about how much he enjoyed the island and his interactions with its native people:

From the moment I saw it, reality surpassed even my fantasies about Tahiti, and I had some of the best times of my life making Mutiny on the Bounty. The filming was done largely on a replica of H.M.S. Bounty anchored offshore, and every day as soon as the director said, "Cut" for the last time, I ripped off my British naval officer's uniform and dove off the ship into the bay to swim with the Tahitian extras working on the movie. Often we only did two or three shots a day, which left me hours to enjoy their company, and I grew to love them for their love of life.[18]

In January 1961, after three months of filming, Reed flew back from location with an "undisclosed ailment".[19] Reportedly, his departure was due to bouts with gallstones and heat stroke, although other reports stated that Reed was instead unhappy over differences with the direction of the story.[16] By that time, the rainy season had started, so filming halted and the unit returned to Hollywood. MGM then demanded that Reed finish the film within 100 days, but the director said he needed 139. The studio fired him. Brando claims in his memoirs that MGM fired Reed because he wanted to make Bligh the hero.[20]

Reed was replaced by Lewis Milestone, in what was his last stint directing a theatrical film. "Reed was used to making his own pictures", said Milestone. "He was not used to producer, studio and star interference. But those of us who have been around Hollywood are like alley cats. We know this style. We know how to survive."[11]

Milestone later said "I felt it would be an easy assignment because they'd been on it for months and there surely couldn't be much left to do."[21] However, he says he found that they had only shot one seven-minute scene, where Trevor Howard issues instructions about obtaining breadfruit.[11]

Filming resumed in March 1961 at MGM studios. Milestone said that for his first two weeks on the film "Brando behaved himself and I got a lot of stuff done", such as the arrival of the Bounty at Tahiti. The director says he "got on beautifully with" the British actors. "They were real human beings and I had a lot of fun."[21]

Milestone says "the trouble started" after the first two weeks. He summarised the cause: "The producer made a number of promises to Marlon Brando which he couldn't keep. It was an impossible situation because, right or wrong, the man simply took charge of everything. You had the option of sitting and watching him or turning your back on him. Neither the producers nor I could do anything about it."[21]

The unit returned to Tahiti in April 1961. Filming was plagued by bad weather and script problems. Richard Harris clashed with Brando, and Brando was frequently late to set and difficult while filming.[16][22]

"Marlon did not have approval of the story", said Milestone. "But he did have approval of himself. If Brando did not like something, he would just stand in front of the camera and not act. He thought only of himself. At the same time, he was right in many things that he wanted. He is too cerebral to play the part of Mr. Christian the way Clark Gable played it."[11]

Milestone said the script was constantly being rewritten by Charles Lederer on set, with input from Rosenberg, Sol Siegel and Joseph Vogel, as well as Brando. Milestone said Lederer often worked on the script with Brando in the morning, and shooting did not start until the afternoon. Milestone said "you had the option of shooting it, but since Marlon Brando was going to supervise it anyway, I waited until someone yelled 'camera' and went off to sit down somewhere and read the paper."[21]

The film ended up costing $10 million more than originally expected.[11] Adding to the turmoil of the production's woes, a Tahitian was killed while filming a canoe sequence.

"I have been in this business a few days but I never saw anything like this", said Milestone. "It was like being in a hurricane on a rudderless ship without a captain. I thought when I took the job that it would be a nice trip. By the time it was finished, I felt as though I had been shanghaied."[11]

"The big trouble was lack of guts by management at Metro", said Milestone. "Lack of vision. When they realised there was so much trouble with the script they should have stopped the whole damn production. If they did not like Marlon's behavior they should have told him that he must do as they wished or else they should have taken him out of the picture. But they just did not have the guts."[11] Shooting was ultimately finished by October 1961.

In May 1962, work was still being done on the script and the film.[12] The studio was unhappy with the ending. A number of writers, including Brando, pitched ideas. Eventually, Billy Wilder suggested the ending that was shot.[23] Milestone refused to direct it, so George Seaton shot Christian's death scene in August 1962.[24]

The Saturday Evening Post ran an article about the making of the film which Brando felt disparaged him. He sued them for $5 million. He got MGM president Joseph Vogel to speak in support of his suit; the tactic backfired and was later used against Vogel when he resigned, not long after the release of the film.[25]

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote: "There's much that is eye-filling and gripping as pure spectacle", but criticized Marlon Brando for making Fletcher Christian "more a dandy than a formidable ship's officer ... one feels the performance is intended either as a travesty or a lark."[26] Variety called the film "often overwhelmingly spectacular" and "generally superior" to the 1935 version, adding, "Brando in many ways is giving the finest performance of his career."[27] Brendan Gill of The New Yorker wrote that the screenwriter and directors "haven't failed, but a genuine success has been beyond their grasp. One reason for this is that they've received no help from Marlon Brando, who plays Fletcher Christian as a sort of seagoing Hamlet. Since what Fletcher Christian has to say is so much less interesting than what Hamlet has to say, Mr. Brando's tortured scowlings seem thoroughly out of place. Indeed, we tend to sympathize with the wicked Captain Bligh, well played by Trevor Howard. No wonder he behaved badly, with that highborn young fop provoking him at every turn!"[28] Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post called the film an "unquestionably handsome spectacular" that "teeters headlong into absurdity" in its third hour, summarizing: "It would seem that the mutiny occurred only because the hero blew his top and is egotistically disturbed because he did so."[29] The Monthly Film Bulletin of the UK criticized Brando for an "outrageously phony upper-class English accent" and the direction for "looking suspiciously like a multiple hack job."[30] Time wrote that the film "wanders through the hoarse platitudes of witless optimism until at last it is swamped with sentimental bilge."[31] The film holds a rating of 70% on review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes based on 20 reviews, with an average score of 6.5/10.[32]

Mutiny on the Bounty's difficult and problematic production, Brando's temperamental and eccentric behavior, the overwhelmingly negative reviews of Brando's performance and the box office failure of the film combined to damage Brando's career and star power which was only revived with the release of The Godfather ten years later. Director Milestone later stated he found Brando's performance in Mutiny on the Bounty "horrible".[33]

The film was the fifth highest-grossing film of 1962 grossing $13,680,000 domestically,[2] earning $7.4 million in US theatrical rentals.[34] However, it needed to make $30 million to recoup its budget[17] of $19 million. This meant the film was a box office flop.[35]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

Ford paid a record $2.3 million for the television rights for one screening in the United States.[41] The film was shown on ABC on Sunday, September 24, 1967,[41] which included a restored prologue and epilogue, cut from release prints of the film before its roadshow premiere, wherein HMS Briton comes across the uncharted island in 1814, and its crew encounters Brown as the only surviving member of the Bounty mutineers (who eventually killed each other out of hate), along with surviving Tahiti islanders, and although Brown is willing to return and face the consequences of their actions, Captain Staines (played by Torin Thatcher) informs him that it is no longer necessary, as the Articles of War had been changed 10 years prior. These pieces were included as bonus features on the film's DVD release in 2006.

Marlon Brando fell in love with Tahiti and in 1966 acquired a 99-year lease on the Tetiaroa atoll.[44] He married Tarita Teriipaia on August 10, 1962. They had two children: Teihotu Brando (born 1963) and Tarita Cheyenne Brando (1970–1995). Brando and Teriipaia divorced in July 1972.