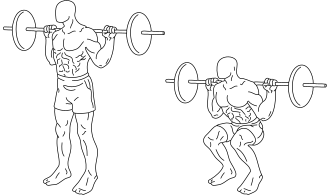

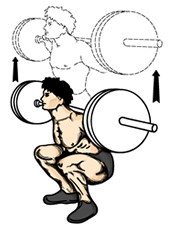

A squat is a strength exercise in which the trainee lowers their hips from a standing position and then stands back up. During the descent, the hip and knee joints flex while the ankle joint dorsiflexes; conversely the hip and knee joints extend and the ankle joint plantarflexes when standing up. Squats also help the hip muscles.

Squats are considered a vital exercise for increasing the strength and size of the lower body muscles as well as developing core strength. The primary agonist muscles used during the squat are the quadriceps femoris, the adductor magnus, and the gluteus maximus.[1] The squat also isometrically uses the erector spinae and the abdominal muscles, among others.[2]

The squat is one of the three lifts in the strength sport of powerlifting, together with the deadlift and the bench press. It is also considered a staple exercise in many popular recreational exercise programs. In powerlifting, it is categorized as raw squats or equipped squats which involves wearing a squat suit.

Form

[edit]

The squat begins from a standing position. Weight is often added and is typically in the form of a loaded barbell. Dumbbells and kettlebells may also be used. When a barbell is used, it may be braced across the upper trapezius muscle, which is termed a high bar squat, or held lower across the back and rear deltoids, termed a low bar squat.[3] Wherever the bar is positioned on the back, various torso bracing actions are taken to ensure that it does not come into direct contact with the spine as this can lead to discomfort and injury. This can be a problem for new squatters who squat in a high bar style as they may not have enough muscle mass to form a cushion for the bar and prevent it from applying pressure directly to their spine.[4] A barbell pad can be used to help alleviate pressure or a low bar style can be used.[5] The squatting movement is initiated by moving the hips back and bending the knees and hips to lower the torso and accompanying weight, then returning to the upright position.

Squats can be performed to varying depths. The competition standard is for the crease of the hip (top surface of the leg at the hip joint) to fall below the top of the knee;[6] this is colloquially known as "parallel" depth.[7] Although it may be confusing, many other definitions for "parallel" depth abound, none of which represents the standard in organized powerlifting. From shallowest to deepest, these other standards are: bottom of hamstring parallel to the ground;[8] the hip joint itself below the top of the knee, or femur parallel to the floor;[9] and the top of the upper thigh (i.e., top of the quadriceps) below the top of the knee.[10] Squatting below parallel qualifies a squat as deep while squatting above it qualifies as shallow.[3] Though the forces on the ACL and PCL decrease at high flexion, compressive forces on the menisci and articular cartilages in the knee peak at these same high angles.[11] This makes the relative safety of deep versus shallow squats difficult to determine.

As the body descends, the hips and knees undergo flexion, the ankle extends (dorsiflexes) and muscles around the joint contract eccentrically, reaching maximal contraction at the bottom of the movement while slowing and reversing descent. The muscles around the hips provide the power out of the bottom. If the knees slide forward or cave in then tension is taken from the hamstrings, hindering power on the ascent. Returning to vertical contracts the muscles concentrically, and the hips and knees undergo extension while the ankle plantarflexes.[3]

Common errors of squat form include descending too rapidly and flexing the torso too far forward. Rapid descent risks being unable to complete the lift or causing injury. This occurs when the descent causes the squatting muscles to relax and tightness at the bottom is lost as a result. Over-flexing the torso greatly increases the forces exerted on the lower back, risking a spinal disc herniation.[3] Another error is when the knee is not aligned with the direction of the toes, entering a valgus position, which can adversely stress the knee joint. An additional common error is the raising of heels off the floor, which reduces the contribution of the gluteus muscles.[12][13]

Muscles used

[edit]Agonist muscles[1]

Stabilizing muscles

- Erector spinae

- Rectus abdominis

- Internal and external obliques

- Hamstrings

- Gluteus medius and minimus

- Gastrocnemius

Equipment

[edit]

Various types of equipment can be used to perform squats.

A power cage can be used to reduce risk of injury and eliminate the need for a spotting partner. By putting the bar on a track, the Smith machine reduces the role of hip movement in the squat and in this sense resembles a leg press.[14] The monolift rack allows an athlete to perform a squat without having to take a couple of steps back with weight on as opposed to conventional racks. Not many powerlifting federations allow monolift in competitions (WPO, GPC, IPO).

Other equipment used can include a weight lifting belt to support the torso and boards to wedge beneath the ankles to improve stability and allow a deeper squat (weightlifting shoes also have wooden wedges built into the sole to achieve the same effect). Wrist straps are another piece of recommended equipment; they support the wrist and help to keep it in a straightened position. They should be wrapped around the wrist, above and below the joint, thus limiting movement of the joint. Heel wedges and related equipment are discouraged by some as they are thought to worsen form over the long term.[15] The barbell can also be cushioned with a special padded sleeve, called a barbell pad. This helps to reduce pressure from the steel barbell on the back.[5]

Chains and thick elastic bands can be attached to either end of the barbell in order to vary resistance at different phases of the movement. This may be done to increase resistance in the stronger upper phase of the movement in order to better meet a person's 1RM for that phase. Bands can also be used to reduce resistance in the lower weaker phase by being hung from a power rack and the barbell being increasingly supported by them as it is lowered. This can help someone to overcome a 'sticking' point. A squat performed using these techniques is called a variable resistance squat.

Variants

[edit]

The squat has a number of variants, some of which can be combined:

Barbell

[edit]- Back squat – the bar is held on the back of the body upon the upper trapezius muscle, near to the base of the neck. Alternatively, it may be held lower across the upper back and rear deltoids. In powerlifting the barbell is often held in a lower position in order to create a lever advantage, while in weightlifting it is often held in a higher position which produces a posture closer to that of the clean and jerk. These variations are called low bar (or powerlifting squat) and high bar (or Olympic squat), respectively.

- Sumo squat – A variation of the back squat where the feet are placed slightly wider than shoulder width apart and the feet pointed outwards.

- Box squat – at the bottom of the motion the squatter will sit down on a bench or other type of support then rise again. The box squat is commonly utilized by powerlifters to train the squat.[citation needed]

- Front squat – the barbell is held in front of the body across the clavicles and deltoids in either a clean grip, as is used in weightlifting, or with the arms crossed and hands placed on top of the barbell. In addition to the muscles used in the back squat, the front squat also uses muscles of the upper back such as the trapezius to support the bar.[16]

- Hack squat – the barbell is held in the hands just behind the legs; this exercise was first known as Hacke (heel) in Germany.[17] According to European strength sports expert and Germanist Emmanuel Legeard this name was derived from the original form of the exercise where the heels were joined. The hack squat was thus a squat performed the way Prussian soldiers used to click their heels ("Hacken zusammen").[18] The hack squat was popularized in the English-speaking countries by early 1900s wrestler, George Hackenschmidt. It is also called a rear deadlift. It is different from the hack squat performed with the use of a squat machine.[19]

- Overhead squat – the barbell is held overhead in a wide-arm snatch grip; however, it is also possible to use a closer grip if balance allows.

- Zercher squat – the barbell is held in the crooks of the arms, on the inside of the elbow. One method of performing this is to deadlift the barbell, hold it against the thighs, squat into the lower portion of the squat, and then hold the bar on the thighs as you position the crook of your arm under the bar and then stand up. This sequence is reversed once the desired number of repetitions has been performed. Named after Ed Zercher, a 1930s strongman.

- Steinborn squat – named after the traditional strongman Henry 'Milo' Steinborn, this unique and risky variation literally turns the squat sideways. The complex lift requires an athlete to stand the barbell up so that is perpendicular to the ground and position themselves underneath. Then, they'll pull the barbell like a lever down across their upper back and receive the load in the squatted position. From there, the lifter must stand the weight up, perform some squats, and return the barbell to the floor in the same reverse fashion that they picked it up.

- Deep knee bend on toes – it is similar to a normal back squat only the lifter is positioned on their forefeet and toes, with their heels raised, throughout the repetition. Usually, the weight used is not more than moderate in comparison to a flat footed, heavy back squat.

- Single leg squat - The single leg squat (SLS), also known as a unilateral squat, involves squatting with one leg instead of two (which is a bilateral squat). Usually the leg which is held off the ground moves behind the person as they squat, but alternatively the person may position it ahead of themselves. Bilateral split squats which significantly increase the work performed by the front leg are sometimes erroneously referred to as single leg squats due to this emphasis. Single leg squats can be used to strengthen a person's stabiliser muscles more so than two legged squats and improve their ability to balance. They can also be used to remove muscle imbalances in the body by ensuring that, when performed alternatively, the right and left leg do the same amount of work. In comparison to two footed squats, the barbell weight only needs to be half of what it would be for the legs to perform the same amount of work i.e. lifting 40 kg using only the left leg, means the left leg is lifting the equivalent of what it does in a two footed squat with 80 kg. This means that the single leg squat can be used in rehabilitation programmes where there is a need to avoid heavier loading of the back.[20]

- Loaded squat jump – the barbell is positioned similarly to a back squat. The exerciser squats down, before moving upwards into a jump, and then landing in approximately the same position. The loaded squat jump is a form of loaded plyometric exercise used to increase explosive power. Variations of this exercise may involve the use of a trap bar or dumbbells.

- Variable resistance squat – In keeping with variable resistance training in general, a variable resistance squat involves altering the resistance during the movement in order that it better matches, in percentage terms, the respective 1RM for each strength phase[a] the person is moving through i.e. more resistance in the higher stronger phase and less in the weaker lower phase e.g. 60 kg in the lower phase and 90 kg in the higher phase. Such an alteration of resistance can be achieved by the use of heavy chains which are attached to either end of the barbell. The chains are gradually lifted from the floor as the barbell is raised and vice versa when it is lowered. Thick elastic bands which are more stretched in the higher phase and less stretched in the lower phase can also be used. Combining heavier partial reps with lighter full reps can also help to train the stronger and weaker phases of the movement so the percentage of 1RM lifted for each phase respectively is more similar. Training with variable resistance squats is a technique used to increase speed and explosive power.[21][22]

- Partial rep – Partial rep squats only move through a partial range of movement (PROM) when compared with full squats which move through a full range of movement (FROM). PROM for a squat usually means the higher stronger phase of a squat's strength phase sequence[a] (strength curve), but may also refer to just squatting for the lower weaker phase. When partial squats are used to strengthen the higher ROM this usually involves significantly increasing the weight in comparison to the weight used for a full squat. The percentage lifted of the stronger higher phase's 1RM can therefore be increased and not limited by the requirement to move through the weaker lower range of movement e.g. a person lifts 100% of his 1RM for the higher stronger phase which is 150 kg. If he did a full squat he would only have been able to do about 66% of his stronger phases 1RM because his 1RM for a full squat, including the weaker lower phase, is 100 kg. Training with heavier partial squats can help to improve general strength and power. It can also be more beneficial for sports and athletics as that ROM is more likely to be required in those activities i.e. it is rare to need to perform a full squat in sport, whereas partial squatting happens frequently. Partial squatting with a heavier weight than a full squat allows for can also help to improve a person's 1RM for a full squat. When partial squatting only the lower phase this is usually to strengthen that relatively weak phase of the lift in order to overcome a sticking point i.e. a point a person gets "stuck" at and finds it difficult to progress past. It is commonly recommended that partial squats are best used in conjunction with full squats.[23][24]

Lunge

[edit]- Split squat – an assisted one-legged squat where the non-lifting leg is rested on the ground a few steps behind the lifter, as if it were a static lunge.

- Bulgarian split squat – performed similarly to a split squat, but the foot of the non-lifting leg is rested on a platform behind the lifter.

Other

[edit]- Belt squat – is an exercise performed the same as other squat variations except the weight is attached to a hip belt i.e. a dip belt

- Goblet squat – a squat performed while holding a kettlebell or dumbbell on to one's chest and abdomen with both hands.

- Smith squat – a squat using a Smith machine.

- Machine hack squat – using a squat machine.[19]

- Trap bar squat – a trap bar is held in the hands while squats are performed. More commonly referred to as "trap bar deadlifts."

- Monolift squat – a squat using a monolift rack.

- Safety squat – a squat performed using a safety squat bar which has a camber in the middle, two handles, and padding. The use of a safety squat bar may help to reduce the risk of causing or aggravating an injury.[25][26]

- Anderson squat - (aka Pin Squat, Bottoms Up Squat) starting the squat from the bottom position.[27]

Body-weight

[edit]

- Body-weight or air squat – done with no weight or barbell, often at higher repetitions than other variants.

- Overhead squat – a non-weight bearing variation of the squat exercise, with the hands facing each other overhead, biceps aligned with the ears, and feet hip-width apart. This exercise is a predictor of total-body flexibility, mobility, and possible lower body dysfunction.

- Hindu squat – also called a baithak, or a deep knee bend on toes. It is performed without additional weight, and body weight placed on the forefeet and toes with the heels raised throughout; during the movement the knees track far past the toes. The baithak was a staple exercise of ancient Indian wrestlers. It was also used by Bruce Lee in his training regime.[28] It may also be performed with the hands resting on an upturned club or the back of a chair.

- Jump squat – a plyometrics exercise where the squatter engages in a rapid eccentric contraction and jumps forcefully off the floor at the top of the range of motion.

- Basic single leg squat – the person stands with one foot on the ground and the other foot raised. They bend their standing leg and move downwards. Their raised leg moves behind them with the knee coming close to the heel of the grounded foot. Due to the extra effort required to balance, one legged squats can help to additionally improve a person's sense of balance.[29] As with other forms of one legged exercise performed alternately, they can also help to mitigate against an excessive strength variation between the legs, as both legs are made to perform the same level of work e.g. in a two legged squat a person's right leg may do 55% of the work and their left leg 45%, which may result in an excessively uneven level of strength developing. By switching between using the right leg and left leg in one legged squats, a person can better ensure that each leg is doing the same level of work i.e. the right or left leg does 100% of the work for each respective one legged squat.[30]

- Pistol squat – a bodyweight single leg squat done to full depth, while the other leg is extended off the floor and positioned somewhere in front. Sometimes dumbbells, kettlebells or medicine balls are added for resistance. Pistol squats may be performed with the foot flat on the floor or with the heel raised.A basic single leg squat

- Shrimp squat – also called the flamingo squat, a version of the pistols squat where instead of extending the non-working leg out in front, it is bent and placed behind the working leg while squatting, perhaps held behind in a hand.[31] Shrimp squats may be performed with the foot flat on the floor or with the heel raised.

- Jockey squat - a half-squat, performed by being balanced on the forefeet throughout the repetition, with fingertips touching across the chest. This squat can be performed quickly and in high repetitions.

- Sissy squat – the knees travel over the toes, stretching the quadriceps and the body leans backwards. Can be done in a special sissy squat machine, and can also be weighted.[32][33][34]

- Sumo Squat - also known as Plie Squat, in this variation legs are wider than shoulder width.

Clinical significance

[edit]Squat is a large muscle-mass resistance exercise.[35] As such, squats acutely produces increases in testosterone (especially in men) and growth hormone (especially in women).[35] Although insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) is not raised acutely by squat exercise, resistance-trained men and women have higher resting IGF-1.[35] Catecholamines (epinephrine, norepinephrine, dopamine) are acutely elevated by resistance exercise, such as squats.[35]

The squat has been used in clinical settings to strengthen lower body musculature with little or no harm after joint-related injury.[36] Young people may benefit by enhanced athletic performance and reduced injury as they mature, and movement competency can ensure independent living in the elderly. [36]

Injury considerations

[edit]Although the squat has long been a basic element of weight training, it has not been without controversy over its safety.

Some trainers claim that squats are associated with injuries to the lumbar spine and knees.[37] Others, however, continue to advocate the squat as one of the best exercises for building muscle and strength. Some coaches maintain that incomplete squats (those terminating above parallel) are both less effective and more likely to cause injury[2] than full squat (terminating with hips at or below knee level).

A 2013 review concluded that deep squats performed with proper technique do not lead to increased rates of degenerative knee injuries and are an effective exercise. The same review also concluded that shallower squats may lead to degeneration in the lumbar spine and knees in the long-term.[38]

Squats used in physical therapy

[edit]Squats can be used for some rehabilitative activities because they hone stability without excessive compression on the tibiofemoral joint and anterior cruciate ligament.[39]

Deeper squats are associated with higher compressive loads on patellofemoral joint[39] and it is possible that people who suffer from pain in this joint cannot squat at increased depths. For some knee rehabilitation activities, patients might feel more comfortable with knee flexion between 0 and 50 degrees because it places less force compared to deeper depths.[citation needed] Another study shows that decline squats at angles higher than 16 degrees may not be beneficial for the knee and fails to decrease calf tension.[40] Other studies have indicated that the best squat to hone quadriceps, without inflaming the patellofemoral joint, occurs between 0 and 50 degrees.[39]

Combining single-limb squats and decline angles have been used to rehabilitate knee extensors.[40] Conducting squats at a declined angle allows the knee to flex despite possible pain or lack of mobilization in the ankle.[40] If therapists are looking to focus on the knee during squats, one study shows that doing single-limb squats at a 16-degree decline angle has the greatest activation of the knee extensors without placing excessive pressure on the ankles.[40] This same study also found that a 24-degree decline angle can be used to strengthen ankles and knee extensors.[40]

Different Sets For Squats

Forced repetitions are used when training until failure. They are completed by completing an additional 2–4 reps (assisted) at the end of the set.[41] Partial repetitions are also used in order to maintain a constant period of tension in order to promote hypertrophy.[41] Lastly, drop-sets are an intense workout done in at the end of a set which runs until failure and continues with a lower weight without rest.

World records

[edit]Men

[edit]- Equipped squat (with multi-ply suit and wraps) – 595 kg (1,312 lb) by Nathan Baptist

(2021)[42]

(2021)[42] - Raw squat (with wraps) – 525 kg (1,157 lb) by Vladislav Alhazov

(2018)[43]

(2018)[43] - Raw squat (with sleeves) – 490 kg (1,080 lb) by Ray Orlando Williams

(2019)[44]

(2019)[44] - Playboy bunny smith machine squat – 453.5 kg (1,000 lb) by Don Reinhoudt

(1979)[45]

(1979)[45] - Cement block smith machine squat – 439.5 kg (969 lb) by Bill Kazmaier

(1981)[46]

(1981)[46] - Double T 'cambered bar' squat (with single-ply suit) – 438 kg (966 lb) by JF Caron

(2022)[47]

(2022)[47] - Steinborn squat – 256.5 kg (565 lb) by Martins Licis

(2019)[48]

(2019)[48] - Squat for reps – 329 kg (725 lb) (with singly ply suit) for 15 reps in one minute by Žydrūnas Savickas

(2014)[49]

(2014)[49] - Squat for reps – 238 kg (525 lb) (with singly ply suit) for 23 reps in one minute by Tom Platz

(1993)[50]

(1993)[50] - Squat for reps – 200 kg (441 lb) (Raw) for 29 reps in one minute by Hafþór Júlíus Björnsson

(2017)[51]

(2017)[51] - Squat for reps – 82 kg (181 lb) (own bodyweight) for 42 reps in one minute by Erikas Dovydėnas

(2022)[52]

(2022)[52] - Most squats in one minute (no added weight/ bodyweight only) – 84 reps by Tourab Nesanah

(2022)[53]

(2022)[53] - Most pistol squats in one minute (no added weight/ bodyweight only) – 52 reps by William Rauhaus

(2016)[54]

(2016)[54] - Most squats in one hour (no added weight/ bodyweight only) – 4,708 reps by Paddy Doyle

(2007)[55]

(2007)[55] - Most squats in one day (no added weight/ bodyweight only) – 25,000 reps by Joe Reverdes

(2020)[56]

(2020)[56]

Women

[edit]- Equipped squat (with multi-ply suit and wraps) – 432.5 kg (953 lb) by Leah Reichman

(2023)[57]

(2023)[57] - Equipped squat (with single-ply suit and wraps) – 335 kg (739 lb) by Galina Karpova

(2012)[58]

(2012)[58] - Raw squat (with wraps) – 320 kg (705 lb) by April Mathis

(2017)[59]

(2017)[59] - Raw squat (with sleeves) – 311 kg (686 lb) by Sonita Muluh

(2024)[60]

(2024)[60] - Squat for reps – 130 kg (287 lb) (with singly ply suit) for 29 reps in two minutes by Maria Strik

(2013)[61]

(2013)[61] - Squat for reps – 67 kg (148 lb) (own bodyweight) for 42 reps in one minute by Karenjeet Bains

(2023)[citation needed]

(2023)[citation needed] - Most sumo squats in one hour (no added weight/ bodyweight only) – 5,135 reps by Thienna Ho

(2007)[62]

(2007)[62]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b A movement may be considered as having any number of strength phases but usually is considered as having two main phases: a stronger and a weaker. When the movement becomes stronger during the exercise, this is called an ascending strength curve i.e. bench press, squat, deadlift. And when it becomes weaker this is called a descending strength curve i.e. chin ups, upright row, standing lateral raise. Some exercises involve a different pattern of strong-weak-strong. This is called a bell shaped strength curve i.e. bicep curls where there can be a sticking point roughly midway.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "BB Squat". ExRx. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ a b Rippetoe M (2007). Starting Strength: Basic Barbell Training, p.8. The Aasgaard Company. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-9768054-2-7.

- ^ a b c d Brown SP (2000). Introduction to exercise science. Lippincott Wims & Wilkins. pp. 280–1. ISBN 0-683-30280-9.

- ^ Pinchas, Yigal (2006). The Complete Holistic Guide to Working Out. Calgary: University of Calgary Press. p. 59. ISBN 1-55238-215-X.

- ^ a b Shepard, Greg; Goss, Kim (2017). Bigger, Faster, Stronger. Leeds: Human Kinetics. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-4925-4581-1.

- ^ "Technical Rules Book 2013" (PDF). International Powerlifting Federation. January 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2013.

- ^ Hanna, Wade (March 2002) Squat depth clarified. USA Powerlifting Online Newsletter. Usapowerlifting.com. Retrieved on 2013-08-05.

- ^ Hi- and Low-bar Squatting. Home.comcast.net. Retrieved on 2013-08-05.

- ^ 6 Things I Really Dislike. T Nation. Retrieved on 2013-08-05.

- ^ A Closer Look at the Parallel Squat. Bigger Faster Stronger, March/April 2008, pp. 36–38.

- ^ Clarkson, HM, and Gilewich, GB (1999) Musculoskeletal Assessment: Joint Range of Motion And Manual Muscle Strength. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins, p. 374, ISBN 0683303848.

- ^ "Squat". lift.net.

- ^ Sandvik E (5 October 2016). "The 11 Worst Squat Mistakes". T NATION. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ Cornacchia, pp. 121, 125.

- ^ McRobert S (1999). The Insider's Tell-All Handbook on Weight-Lifting Technique. CS Publishing. ISBN 9963-616-03-8.

- ^ "Front Squat". ExRx. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ Hackenschmidt, George (1908). The Way To Live in Health and Physical Fitness. York. p. 70.

((cite book)): CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Legeard, Emmanuel (2008). Les Fondamentaux. Paris. p. 218. ISBN 978-2851806789.

((cite book)): CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "Machine Hack Squat". bodybuilding.com. 16 September 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ Wiliam Eliassen & Atle Hole Saeterbakken & Roland van den Tillaar (2018). "Comparison of bilateral and unilateral squat exercises on barbell kinematics and muscle activation". International Journal of Sports Physiotherapy. 13 (5): 871–881. PMC 6159498. PMID 30276019.

- ^ Bosse, Christian (5 January 2017). "Accommodating Resistance Training – Bands and Chains". christianbosse.com. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ Barker, Matthew (15 August 2017). "Chains & Bands Are The Secret To Stronger Front Squats". Barbend.com. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ Wayland, William (17 November 2014). "Salvaging the partial squat". Powering-through.com. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ Bryant, Josh (11 July 2017). "Partials vs. full rom: which is better for strength?". muscleandfitness.com. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ Bret Contreras PhD, Glen Cordoza (2019). The Glute Lab. Victory Belt Publishing Inc. p. 447. ISBN 978-1628603-46-0.

- ^ Taylor CSCS, Ryan (29 April 2019). "6 Reasons to Train with a Safety Squat Bar". Body Building. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ "Anderson Squat – How It Benefits Your Training". Barbend.com. 28 November 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ Lee, Bruce,'Preliminaries' in The Tao of Jeet Kune Do, California: Ohara Publications, 1975, p.29

- ^ Shephard, John (20 March 2020). "Exercise focus – single leg bodyweight squat". Athletics Weekly. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ Aschwanden, Christie. "Strong Legs". Runner's World. February 2007: 32.

- ^ Periodic Table of Bodyweight Exercises with Clickable Videos. Strength.stack52.com. Retrieved on 2015-04-24.

- ^ Mark Dutton (2020). Dutton's Orthopaedic: Examination, Evaluation and Intervention, Fifth Edition. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 1009. ISBN 9781260440119.

- ^ "Weighted sissy squat". bodybuilding.com. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Sissy Squat Video Guide". Muscle and Strength. 16 September 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d Kraemer WJ, Ratamess NA (2005). "Hormonal responses and adaptations to resistance exercise and training". Sports Medicine. 35 (4): 339–361. doi:10.2165/00007256-200535040-00004. PMID 15831061.

- ^ a b Myer GD, Kushner AM, McGill SM (2014). "The back squat: A proposed assessment of functional deficits and technical factors that limit performance". Strength and Conditioning Journal. 36 (6): 4–27. doi:10.1519/SSC.0000000000000103. PMC 4262933. PMID 25506270.

- ^ Cornacchia, p. 120.

- ^ Hartmann H, Wirth K, Klusemann M (October 2013). "Analysis of the load on the knee joint and vertebral column with changes in squatting depth and weight load". Sports Medicine. 43 (10): 993–1008. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0073-6. PMID 23821469. S2CID 34801267.

- ^ a b c Jaberzadeh S, Yeo D, Zoghi M (September 2016). "The Effect of Altering Knee Position and Squat Depth on VMO : VL EMG Ratio During Squat Exercises". Physiotherapy Research International. 21 (3): 164–173. doi:10.1002/pri.1631. PMID 25962352.

- ^ a b c d e Richards J (2008). "A Biomechanical Investigation of a Single-Limb Squat: Implications for Lower Extremity Rehabilitation Exercise". Journal of Athletic Training. 43 (5): 477–482. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.477. PMC 2547867. PMID 18833310.

- ^ a b Ferraresi, Cleber; Rodrigues Bertucci, Danilo, eds. (2016). Strength Training: Methods, Health Benefits and Doping. Hauppauge, New York: Nova Publishers. ISBN 978-1-63484-157-3. OCLC 933581166.

- ^ "Powerlifter Nathan Baptist Hits All-Time World Record Equipped Squat of 594.7 Kilograms (1,311 Pounds)". Barbend.com. 31 July 2023. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ "Vlad Alhazov Squats 1,157 with Wraps Only!!!". Powerlifting Watch. 23 December 2018. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023.

- ^ Boly, Jake (3 March 2019). "Ray Williams Squats an Incredible 490kg (1,080 LBS) RAW". BarBend. Archived from the original on 8 October 2023.

- ^ "1,000 LB Squat No Sweat for Don Reinhoudt in 1979". SBD World’s Strongest Man Facebook page. 28 January 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ "Bill Kazmaier sets UNDEFEATED Max. Squat EVENT RECORD World's Strongest Man". The World’s Strongest Man YouTube page. 8 August 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ "2022 Arnold Strongman Classic Event 1". YouTube.

- ^ "Strongman Martins Licis Steinborn Squats an Incredible 565 lb World Record". Barbend.com. 1 August 2023. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ "Žydrūnas Savickas Workout Routine and Diet Plan". fitnessreaper.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Tom Platz Squat & Leg Workout". Old School Labs. 22 March 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ English, Nick (14 June 2018). "Throwback: Thor Bjornsson Squats 200kg For 29 Grueling Reps". BarBend. Archived from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Most times to squat lift own bodyweight in one minute (male)". Guinness World Records. 10 September 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Most squats in one minute (male)". Guinness World Records. 9 September 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Most squats in one minute (single leg)". Guinness World Records. 27 July 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "Most squats in one hour". Guinness World Records. 8 November 2007.

- ^ "Most squats in 24 hours (male)". Guinness World Records. 5 September 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ "Leah Reichman (F)". Openpowerlifting.org. 15 April 2023. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ "Galina Karpova (F)". Openpowerlifting.org. 24 February 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ "April Mathis (F)". Openpowerlifting.org. 1 April 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ "Sonita Muluh (F)". Openpowerlifting.org. 15 June 2024. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Glenday C (2013). 2013 Guinness World Records Limited. Guinness World Records Limited. pp. 104. ISBN 978-1-908843-15-9.

- ^ "Most sumo squats in one hour". Guinness World Records. 16 December 2007.

Bibliography

[edit]- Cornacchia L, Bompa TO, Di Pasquale MG, Di Pasquale M (2003). Serious strength training. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. ISBN 0-7360-4266-0.

External links

[edit]- WebMD summary of health benefits of squats

- Video of squat recommendations with demonstration by a chiropractor