The Eight Great Events (aṣṭamahāpratihārya)[2] are a set of episodes in the life of Gautama Buddha that by the time of the Pala Empire of North India around the 9th century had become established as the standard group of narrative scenes to encapsulate the Buddha's life and teachings. As such they were frequently represented in Buddhist art, either individually or as a group, and recounted and interpreted in Buddhist discourses.

The Eight Great Events are: the Birth of the Buddha, the Enlightenment, the First Sermon, the Monkey's offering of honey, the Taming of Nalagiri the elephant, the Descent from Tavatimsa Heaven, the Miracle at Sravasti and his death or Parinirvana.[3] Each event had taken place at a specific location, which had become a place of pilgrimage,[4] and there was a matching set of "Eight Great Places", "Attha-mahathanani" in Pali, where the events took place. Apart from his birth in modern Nepal (just, some 10 km from the border), all the events took place in Bihar or Uttar Pradesh in north-east India.[5]

Before and after this period there were other groupings, both smaller and larger, with 4, 5, 20, and other much larger groups found. A grouping of four events, the Birth, Enlightenment, First Sermon and Death was the most prominent, consisting of very important life-events.[6] Larger groups, such as the 43 on the 20th-century Ivory carved tusk depicting Buddha life stories in New Delhi, tend to have more from the Buddha's early life. A 15th-century Tibetan painted thanka has 32 scenes, of which 15 precede the Enlightenment.[7]

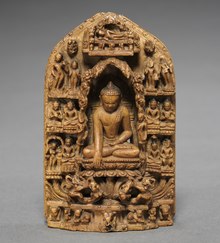

A common iconography for steles in relief had a larger central Buddha figure, normally showing the Enlightenment, surrounded by smaller scenes showing the others. The Parinirvana, with a reclining Buddha, is normally at the top, over the larger figure, with the rest three high on each side. In small versions of such a scheme the space available means that events are distinguished largely by the mudra or hand gesture of the Buddha.[8] Sets of paintings, which only survive from rather later, show all eight at similar sizes.

The iconography of the events reflects the elaborated versions of the Buddha's life story that had become established from about 100 AD in Gandharan art and elsewhere, such as Sanchi and Barhut, and were given detailed depictions in cycles of scenes, typically rectangular, on the many spaces provided by large stupas and other Buddhist constructions. From early on, the accounts of some events varied considerably. Small reliefs only allow very compact depictions of the scenes, with very few if any other figures than the Buddha. These are simplified versions of much larger relief sculptures of each individual event. Larger depictions, such as paintings, are by contrast often crowded with other figures.[9]

Apart from the Birth and Death, the other events divide into two scenes where the Buddha is normally standing, the Descent and taming Nalagiri, leaving four where he is sitting in a meditation position, although in The Monkey's offering he is sometimes seated on something, with his legs coming down. The steles are typically arranged with the horizontal scene of the death across the top, above the main image, then the two scenes where Buddha stands the highest on each side. The Birth is normally at the bottom of one side, more often the viewer's left, and the meditating scenes fill the other spaces, including the larger main image.[10]

A bronze model stupa from 8th or 9th-century Nalanda in the National Museum, New Delhi has the events arranged around a middle drum section.[11] Later works, from the following centuries and several different countries, continue the broad stele format with variations, and often differences in the scenes depicted.[12]

Queen Maya, mother of the Buddha, was returning to her parents' home to give birth. She stopped for a walk in the park or grove at Lumbini, now in Nepal. Reaching up to hold a bough of a sal tree (Shorea robusta), labour began. Maya standing with her right hand over her head, holding a curving bough, is the indispensable part of the iconography; this was a pose familiar in Indian art, often adopted by yakshini tree-spirits. Maya's feet are usually crossed, giving a graceful tribhanga pose. The Buddha emerged miraculously from her side, which is usually shown in small depictions with him as though flying. In larger ones two male figures stand to the left, representing the Vedic gods Indra, who reaches out to hold the baby, and Brahma standing behind him. Maya's sister Pajapati may support her to the right, and maids may stand on the right, and apsaras or other spirits hover above.[13]

The Buddha was able to stand and take seven steps almost immediately,[14] ending by standing on a lotus flower, and the baby standing on this may be shown; in East Asia this subject became popular by itself, the most famous and one of the earliest at the Todaiji in Nara, Japan.[15] Buddha's first bath is also sometimes shown in the same scene; two Nagaraja (Nāga kings) perform the bathing, and maids may attend.[16] Symbolic re-enactments of this form part of the rituals celebrating Buddha's birthday or Vesak in many countries.[17]

This took place at Bodh Gaya, under the famous Bodhi Tree, a probable descendant of which survives beside the Mahabodhi Temple. Buddhist tradition recounts that the enlightment was preceded by the "assault of Mara", a demon king, who challenged the Buddha's right to acquire the powers that enlightenment brought, and asked him for a witness to attest his right to achieve it. In reply Buddha touched the ground with his right hand outstretched, asking Pṛthivi, the devi of the earth, to witness his enlightenment, which she did.[18][19]

The foliage of the Bodhi Tree may be shown above Buddha's head. Buddha is always shown seated in the lotus position, reaching the fingers of his right hand down to touch the ground, which is called the bhūmisparśa or "earth witness" mudra. Larger depictions may show Mara and his army of demons, or his three beautiful daughters, who attempt to prevent the Buddha's enlightenment by distracting him from meditation with seductive movements;[20] modern South-East Asian depictions of this can be rather lurid.[21]

This event in Buddha's life is most commonly the large central scene in groups, as in the Jagdispur stele, where dozens of small demons surround the Buddha.[22]

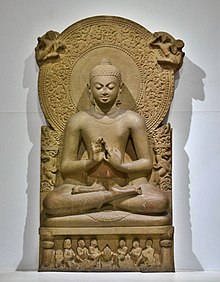

This is also known as the "Sermon in the Deer Park", and is recorded in the text called the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta ("The Setting in Motion of the Wheel of the Dharma Sutta"). Among other key Buddhist doctrines it set out the Four Noble Truths and the Middle Way. It was delivered at Sarnath, some weeks after his enlightenment, to five named disciples, who may be shown if they can be fitted in. Buddha is seated, normally in the lotus position, and his hands are always shown in the Dharmachakra Pravartana Mudrā, where his two hands mime his metaphor of "setting in motion the Wheel of the Dharma". This is generally only used in images of the Buddha when representing this moment.[24]

This or the Enlightenment are usually the main large scene in stele groups. In larger groups a wheel may figure, as in a 5th-century stele at Sarnath, and sometimes one or two deer, referring to the location. These may be on the front of the base of Buddha's throne, where the disciples may also appear, much smaller than the Buddha.[25]

This took place during the Parileyyakka Retreat at Vaishali. It is also called the Monkey's Offering of Honey. A monkey offers honey to Buddha, who is shown in the lotus position, with his begging bowl in his lap. In some versions the Buddha initially rejected the honey because it had bee larvae, ants or other insects in it, but after the monkey carefully removed these with a twig his gift was accepted.[27]

It is the most obscure of the events, and relatively uncommonly depicted before it became one of the Eight Great Events around the 8th century.[28] It is also rather unclear from the texts why it is connected to Vaishali,[29] but this was an important city with other connections with the Buddha, who preached his last sermon there. He left his begging bowl in the city when he departed, and this, which became an important cetiya or relic, is the indispensable identifying element in the most reduced images, when even the monkey is not shown. The monkey may be shown, and also an elephant who also protected Buddha and gave him water. Each of these had divergent and initially unhappy after-stories. The monkey, overcome with excitement when his gift is accepted, fell or jumped down a well in some versions, but was later saved and turned into a deva,[30] or was reborn as a human who joined Buddha's sangha as a monk.[31]

The Buddha's cousin and brother-in-law Devadatta is portrayed in Buddhist tradition as an evil and schismatic figure. He is said to have attempted to kill Buddha by setting the ferocious elephant Nalagiri on Buddha, at Rajgir. Buddha pacifies the elephant, who kneels before him.[32] Buddha is usually shown standing, with his hand in the abhayamudra, with his right hand held open and the palm vertical. The elephant is usually much smaller, often at the scale of a small dog compared to Buddha, and shown bowing to Buddha. Sometimes a small figure of Ananda, a close disciple, stands by Buddha, as in some texts of the story he remained with Buddha during the episode.[33]

Some years after his enlightenment, Buddha visited the Tavatimsa heaven, where he was joined by his mother (from the Tushita heaven). For three months he taught her the Abhidhamma doctrine, before descending again to earth at Sankassa. Larger depictions show the Buddha descending the central one of three ladders or steps, often attended by Indra and Brahma, lords of the Tavatimsa heaven,[34] who may remain at the top of any steps, but in simplified depictions they flank a standing Buddha on either side, at a much smaller scale, sometimes one holding a parasol over the Buddha. Buddha makes the varadamudra. A small figure of the nun Utpalavarana may be waiting for the Buddha below.[35] The event is still celebrated in Tibet, in a festival called Lhabab Duchen.[36]

This is also called the Twin Miracle, performed at Shravasti (Sravasti etc). In a "miracle contest" with the Six Heretical Teachers, the Buddha performed two miracles. The first and more commonly depicted is known as the "multiplication of Buddhas", where Buddha baffles the others by multiplying his form into several Buddhas, who preach to the assembled crowd. In small pieces, however, only one Buddha figure may be shown.[37]

In the other, Buddha makes flames rise up from his upper body, while water flows from the lower parts.[38] This is more rarely depicted, with only five reliefs known from Gandhara.[39] The depiction indicates both elements by patterns on the relief, with the Buddha standing with his hand in the abhayamudra. Another miracle, with the miraculous growth of a mango tree,[40] is shown in earlier reliefs at Sanchi, but not in depictions of the Eight Great Events.

Also called the Parinirvana ("entry to nirvana"). It took place at Kushinagar, Uttar Pradesh. It is normally depicted in stele groups across the centre of the top, above the main figures, with a reclining Buddha with his head to the left, usually on a raised couch or bed. As many followers as space allow are crowded round the bed, in early versions making extravagant gestures of grief; these return in later Japanese paintings.[41]

In Sri Lanka, artists often showed the Buddha alive and awake,[42] but elsewhere the moment after death is usually represented. Sometimes the body is already wrapped in a shroud, but usually the face, as if asleep, is turned towards the viewer. Traditionally the death took place between two sal trees (the same species under which he was born), which may be shown behind him, as may their tree-spirits in the branches.[43] The texts (the Pali Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta and Sanskrit-based Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra are the earliest) say he lived to be eighty, but he is shown as young, as he is in all depictions of him as an adult.[44]

One of the earliest surviving sets, if not the earliest, of the eight scenes on a single piece of stone is in the museum at Sarnath, dating from the 7th century, and a little over 3 foot high. Here there is no larger main image, with all eight scenes at the same size, arranged in two columns of four scenes, with a grid of narrow plain borders enclosing them. They are not in exact chronological sequence, with for example the Birth at the bottom of the left column, the First Sermon at top left, and the Death at top right. The spaces for each scene are slightly wider than they are high, allowing at least three figures in each scene, and sometimes more.[47]

Another broken and damaged stele from Sarnath (illustrated) has a similar grid style; five scenes survive, but there may have been others, as the Death is missing and the stone is broken off at the top. In this the lowest scene, of the birth, is double width and includes more detail, but is badly damaged. The Descent has a small flight of steps.[48]

The Jagdishpur stele is a rare survival of a very large stele with the Eight Great Events, rather than just showing a single one as most large steles do. At over 3 metres tall, and probably 10th-century, it is "the largest Buddhist devotional image to survive from this period in north India". Jagdishpur is some two kilometres from the main remains of the great Buddhist college of Nalanda, where it may have originally been placed. When the image was photographed in the 1870s it was outside a small Hindu temple, worshiped as a murti of a Hindu goddess; now moved inside, it remains in worship.[49] One scholar connects groups of the Eight Great Events specifically with Nalanda, both a huge centre of learning and of the production of sculpture.[50] The Jagdishpur stele is unusual in including five Vedic or Hindu deities in the Descent scene. From left, these are Surya and Brahma, then on the other side of the Buddha, Indra, Vishnu and Shiva.[51]