Tuition fees were first introduced across the entire United Kingdom in September 1998 under the Labour government of Tony Blair to help fund tuition for undergraduate and postgraduate certificate students at universities; students were required to pay up to £1,000 a year for tuition.[1][2] However, only those who reach a certain salary threshold (£21,000) pay this fee through general taxation. In practice, higher education (HE) remains free at the point of entry in England for a high minority of students.[citation needed]

The state pays for the poorest or low income to access a university, thus university attendance remains high.[3] There are record levels of disadvantaged students accessing a university in England.[3] As a result of the devolved national administrations for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, there are now different arrangements for tuition fees in each of the nations. The Minister of State for Universities has oversight over British universities and the Student Loans Company.

History

From 1945 onwards, fees were generally covered by local authorities and were not paid by students. This was formalised by the Education Act 1962 which established a mandate for local authorities to cover the fees. In practice, this mean that fees were not charged from then until the repeal of the act in 1998. During the period university tuition was effectively available for free.[4]

Dearing report and £1,000 fee cap (1998)

In May 1996, Gillian Shephard, Secretary of State for Education and Employment, commissioned an inquiry, led by the then Chancellor of the University of Nottingham, Sir Ron Dearing, into the funding of British higher education over the next 20 years.[5] This National Committee of Inquiry into Higher Education reported to the new Labour Government, in the summer of 1997, stating additional billions of funding would be needed over the period, including £350 million in 1998–99 and £565 million in 1999–2000, in order to expand student enrolment, provide more support for part-time students and ensure adequate infrastructure.[6][7] The committee, as part of its brief, had controversially investigated the possibility of students contributing to the cost of this expansion, either through loans, a graduate tax, deferred contributions or means-testing state assistance, as their report notes:[8]

20.40 We do not underestimate the strength of feeling on the issue of seeking a contribution towards tuition costs: nor do we dispute the logic of the arguments put forward. A detailed assessment of the issues has, however, convinced us that the arguments in favour of a contribution to tuition costs from graduates in work are strong, if not widely appreciated. They relate to equity between social groups, broadening participation, equity with part-time students in higher education and in further education, strengthening the student role in higher education, and identifying a new source of income that can be ring-fenced for higher education.

20.41 We have, therefore, analysed the implications of a range of options against the criteria set out in paragraph 20.2. There is a wide array of options from which to choose, ranging from asking graduates to contribute only to their living costs to asking all graduates to contribute to their tuition costs. We have chosen to examine four options in depth.

In response to the findings, the Teaching and Higher Education Act 1998 was published on 26 November 1997, and enacted on 16 July 1998, part of which introduced tuition fees in all the countries of the United Kingdom.[9]

The act introduced a means-tested method of payment for students based on the amount of money their families earned.[10] Starting with 1999–2000, maintenance grants for living expenses would also be replaced with loans and paid back at a rate of 9% of a graduate's income above £10,000.[9]

Following devolution in 1999, the newly devolved governments in Scotland and Wales brought in their own acts on tuition fees. The Scottish Parliament established, and later abolished a graduate endowment to replace the fees.[11] Wales introduced maintenance grants of up to £1,500 in 2002, a value which has since risen to over £5000.[12]

Higher Education act and £3,000 fee cap (2004)

In England, tuition fee caps rose with the Higher Education Act of 2004. Under the Act, universities in England could begin to charge variable fees of up to £3,000 a year for students enrolling on courses from the academic year of 2006–07 or later. The passing of the aforementioned act caused political controversy due to the influence of Scottish Labour MPs on the vote, which passed with a majority of just five.[13] This policy was also introduced in Northern Ireland in 2006–07 and introduced in Wales in 2007–08. In 2009–10 the cap rose to £3,225 a year to take account of inflation.[14]

Browne review and £9,000 fee cap (2012)

Tuition fees were a major concern at the 2010 general election. The Liberal Democrat party entered the election on a pledge to abolish tuition fees, but had already made preparations to abandon the policy before the election took place.[15] The party entered into coalition government with the Conservatives, who supported an increase in fees. Following the Browne Review the cap was controversially raised to £9,000 a year, approximately treble the previous cap; this sparked large student protests in London. The intention from the government of the time was that most universities would charge about £6,000, and that the £9,000 rate would only be charge in "exceptional" circumstances.[16] In practice most universities immediately began to charge the maximum £9,000 fee.[17] A judicial review against the raised fees failed in 2012, and so the new fee system came into use that September.[18]

The Liberal Democrats conceded that their U-turn on the issue contributed to their defeat at the 2015 election, during which 48 of their 56 seats were lost; the election returned a Conservative majority.[19] Further adjustments were put forth in the 2015 budget, with a proposed fee increase in line with inflation from the 2017–18 academic year onwards, and the planned scrapping of maintenance grants from September 2016.[20] The changes were debated by the Third Delegated Legislation Committee in January 2016, rather than in the Commons. The lack of a vote on the matter drew criticism, as by circumventing the Commons the measures "automatically become law".[21] Tuition fees and perceptions about them are directly linked to satisfaction.[22]

May reform, and frozen fees (2018)

In February 2018, Prime Minister Theresa May launched a review of post-18 education funding, including university funding and possible alternatives to tuition fees and loans.[23] The move was designed to appeal to students,[24] who had voted in large numbers against the government in the 2017 general election and caused the Conservative Party to lose their majority.[25] The review resulted in the expansion of vocational studies in England, and the new T-levels.[26][27][28] In February 2020, Labour Party leadership candidate Keir Starmer (who went on to win the 2020 Labour leadership election), promised to maintain the Labour Party's commitment to abolishing tuition fees,[29] but later indicated that Labour would not pursue free tertiary education should they win the next election.[30][31] This U-turn on policy was criticised by the Green Party of England and Wales, who in contrast support scrapping university tuition fees in the UK, as well as abolishing outstanding debts for undergraduate tuition fees and maintenance loans, alongside any related interest fees.[32][33]

The fees remained frozen at £9,250 into the early 2020s. By 2023 this had led to a crisis in university funding as high inflation had eroded the value of tuition fees. The £9,250 fees charged in 2023 were worth only £6,500 in 2012 terms.[34] This was the cause of mass-layoffs in the sector beginning in late 2023, affecting 50 institutions.[35] By 2024 universities were generally taking on domestic students at a loss, with the actual cost of tuition around £11,000; or £12,500 in Russell Group universities. Universities have made up the difference by charging higher fees to international students, as their fees are unlimited, but international applications began to decline that year after the government tightened visa rules. Approximately 40% of UK universities are currently running budget deficits, and the Office for Students has forecast that this may lead to mergers and closures of universities without intervention.[36]

Current systems

England

In England, undergraduate tuition fees are capped at £9,250 a year for UK and Irish students. Due to Brexit, starting in autumn 2021, EU, other EEA and Swiss nationals are no longer eligible for the home fee status, meaning higher fees and no access to UK government loans unless they have been granted a settled or pre-settled status under the EU Settlement Scheme.[39][40][41] Around 76% of all institutions charged the full amount of tuition fees in 2015–16.[42] A loan of the same size is available for most universities, although students at private institutions are only eligible for £6,000 a year loans.

Since 2017–18, the fee cap is meant to be raised in line with inflation. In October 2017, Prime Minister Theresa May announced that tuition fees would be temporarily frozen at £9,250.[43] As of 2018[update], this temporary freeze remained in place and was expected to be extended as a university funding review is carried out.[44] The latter, which was launched by Theresa May, was chaired by Philip Augar.[44]

In the 2015 spending review, the government also proposed a freeze in the repayment threshold for tuition fee loans at £21,000.[45][46]

Effect

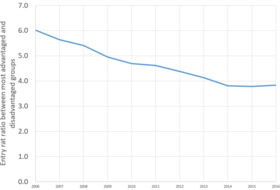

Many commentators suggested that the 2012 rise in tuition fees in England would put poorer students off applying to university.[47] However, the gap between rich and poor students has slightly narrowed (from 30.5% in 2010 to 29.8% in 2013) since the introduction of higher fees.[48] This may be because universities have used tuition fees to invest in bursaries and outreach schemes.[49] In 2016, The Guardian noted that the number of disadvantaged students applying to university had increased by 72% from 2006 to 2015, a bigger rise than in Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland.[50] It wrote that most of the gap between richer and poorer students tends to open up between Key Stage 1 and Key Stage 4 (i.e. at secondary school), rather than when applying for university, and so the money raised from tuition fees should be spent there instead.[50]

A study by Murphy, Scott-Clayton, and Wyness found that the introduction of tuition fees had "increased funding per head, rising enrolments, and a narrowing of the participation gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students".[51]

Northern Ireland

Tuition fees are currently capped at £4,030 in Northern Ireland, with loans of the same size available from Student Finance NI.[52] Loan repayments are made when income rises above £17,335 a year, with graduates paying back a percentage of their earnings above this threshold.[53]

Scotland

Tuition fees are handled by the Student Awards Agency Scotland (SAAS), which does not charge fees from what it defines as "Young Students", or "Dependent Students". Young Students are defined as those under 25, without dependent children, marriage, civil partnership or cohabiting partner, who have not been outside of full-time education for more than three years.[54] Fees exist for those outside the young student definition. The tuition fees are usually £1,820 for undergraduate courses for Scottish & Irish students, and £9,250 for students from the rest of the UK. Due to Brexit, from Autumn 2021 EU students will have to pay international tuition fees in Scotland ranging from £10,000 to £26,000 per year depending on the university and degree type unless they have been granted a settled or pre-settled status under the EU Settlement Scheme.[55][56][57] At the postgraduate level, Scots and RUK usually pay the same amount, commonly between £5,000 and £15,000 per year, while tuition fees for international students can run as high as £30,000 per year.[56]

Fee discrimination against students from the rest of the UK has been challenged in the past but deemed legal.[58][59] The Scottish government confirmed in April 2019 that, with regards to tuition fees, EU students would be treated the same as Scottish students for their whole course if they begin studies up until 2020.[60]

The system has been in place since 2007 when graduate endowments were abolished.[61] Labour's education spokesperson Rhona Brankin criticised the Scottish system for failing to address student poverty.[62] Scotland has fewer disadvantaged students than England, Wales or Northern Ireland and disadvantaged students receive around £560 a year less in financial support than their counterparts in England do.[49]

Wales

In Wales tuition fees are capped at £9,250[63] for all UK students as of September 2024, having increased by £250 from the previous £9,000. Welsh students may apply for a non-means tested tuition fee loan to cover 100 per cent of tuition fee costs wherever they choose to study in the UK.[64]

Welsh students used to be able to apply for fee grants of up to £5,190, in addition to a £3,810 loan to cover tuition fee costs.[65] However, the Welsh Government changed this system after the Diamond Review was published. Today students have access to a means tested loan system where students from the poorest households can be eligible for a grant of up to £10,124 if studying in London or up to £8,100 if studying in the rest of the UK.[66] The changes became effective for students starting University in September 2018. The Welsh Government argued this would allow for higher maintenance loans and grants and these costs are the biggest barrier for poorer students to attend University.[67]

Interest fees

Students and graduates pay interest fees on student loans. Interest starts being added to the student loan from when the first payment is made.[68] In 2012 this rate was set at the Retail Price Index (RPI) plus up to 3% depending on income. Students who started university between 1998 and 2011 pay Bank of England base rate plus 1% or RPI, whichever is lower. Students who started university before 1998 pay interest set at the RPI rate. As a consequence of the 2012 change, students who graduated in 2017 pay between 3.1% and 6.1% interest, despite the Bank of England base rate being 0.25%.[69] In 2018, interest fees rose again, this time to 6.3% for anyone who started studying after 2012.[70]

If those who have taken out a student loan do not update their details with the Student Loans Company when receiving a letter or an email to update their employment status, or upon leaving the UK for 3 or more months, start a new job or become self-employed, or stop working, then they can possibly face a higher interest rate on their loan.[71]

In June 2019, the Brexit Party stated it would scrap all interest paid on student tuition fees and has suggested reimbursing graduates for historic interest payments made on their loans.[72] In August 2019, government figures uncovered by the Labour Party showed that "students will owe a staggering £8.6bn in interest alone on their loans within five years ... almost double the current debt".[73][74]

Possible alternatives

There have been two main proposed alternative ways of funding university studies: from general taxation or by a graduate tax.

Funding from general taxation

Tuition is paid for by general taxation in Germany, although only around 30% of young people gain higher education qualification there, whereas in the UK the comparable figure is 48%.[75][76] Fully or partly funding universities from general taxation has been criticised by the Liberal Democrats as a 'tax cut for the rich and a tax rise for the poor' because people would be taxed to pay for something that many would not derive a benefit from, while graduates generally earn more due to their qualifications and only have to pay them back.[77]

Jeremy Corbyn, former Labour leader, stated that he would have removed tuition fees and would have instead funded higher education by increasing national insurance and corporation tax.[78] In the long term this plan would have been expected to cost the government about £8 billion a year.[79]

In July 2017, Lord Adonis, former Number 10 Policy Unit staffer and education minister largely responsible for introducing tuition fees, said that the system had become a "Frankenstein's monster" putting many students over £50,000 in debt. He argued the system should either be scrapped or fees reverted to between £1,000 and £3,000 per the initial scheme.[80][81]

Graduate tax

During the 2015 Labour leadership election, Andy Burnham said that he would introduce a graduate tax to replace fees. He was ultimately unsuccessful in his bid for leadership. A graduate tax has been criticised because there would be no way to recover the money from students who move to a different country, or foreign students who return home.[82]

See also

- Free education

- Right to education

- Socialist Students

- Student Left Network

- Universal access to education

References

- ^ "BBC Q&A: Student Fees". BBC News. 9 July 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ Stuart Alley and Mat Smith (27 January 2004). "Timeline: Tuition fees". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Statistics: participation rates in higher education". GOV.UK. 31 October 2019. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ "History & Policy". History & Policy. 8 February 2016.

- ^ Anderson, Robert (8 February 2016). "University fees in historical perspective". History & Policy. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ "The Dearing Report". BBC Politics 1997. BBC. 1997. Archived from the original on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ "The Dearing Report - List of recommendations". Leeds.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 21 December 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ Dearing, Ronald. "Higher Education in the learning society (1997) - Main Report". Education In England. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ a b "Teaching and Higher Education Act". BBC News. 6 May 1999. Archived from the original on 7 April 2003. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ Bolton, Paul (23 November 2010). "Tuition Fee Statistics" (PDF). Library of the House of Commons. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 December 2010. Page 2, section 1.1

- ^ Bolton, Paul (23 November 2010). "Tuition Fee Statistics" (PDF). Library of the House of Commons. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 December 2010. Page 3, section 1.4

- ^ "Grants return sets Wales apart". BBC News. 12 February 2002. Archived from the original on 26 May 2009. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ "Scots MPs attacked over fees vote". 27 January 2004. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ Bolton, Paul (23 November 2010). "Tuition Fee Statistics" (PDF). Library of the House of Commons. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 December 2010. Page 2, section 1.2

- ^ Watt, Nicholas; correspondent, chief political (12 November 2010). "Revealed: Lib Dems planned before election to abandon tuition fees pledge". The Guardian.

- ^ Vasagar, Jeevan; Shepherd, Jessica (3 November 2010). "Willetts announces student fees of up to £9,000". The Guardian.

- ^ Paige, Jonathan (16 May 2011). "University fees table – why charge less than the max?". The Guardian.

- ^ "Tuition fees case: Callum Hurley and Katy Moore lose". BBC News. 17 February 2012. Archived from the original on 31 December 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ Weaver, Matthew (12 May 2015). "Nick Clegg's tuition fees 'debacle' undermined trust, says Norman Lamb". The Guardian.

- ^ "Student maintenance grants scrapped". BBC News. 8 July 2015. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ Beattie, Jason (14 January 2016). "Tories bypass MPs to sneak through law abolishing all student grants". mirror. Archived from the original on 17 January 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ Maxwell-Stuart, Rebecca; Taheri, Babak; Paterson, Audrey S.; O'Gorman, Kevin; Jackson, William (24 November 2016). "Working together to increase student satisfaction: exploring the effects of mode of study and fee status". Studies in Higher Education. 43 (8): 1392–1404. doi:10.1080/03075079.2016.1257601. S2CID 55674480.

- ^ "Prime Minister launches major review of post-18 funding". gov.uk. Archived from the original on 14 April 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ Riley-Smith, Ben (30 September 2017). "Theresa May's tuition fees revolution to win over students". The Telegraph.

- ^ Travis, Alan (9 June 2017). "The youth for today: how the 2017 election changed the political landscape". The Guardian.

- ^ "Introduction of T Levels". GOV.UK. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ "T Levels | The Next Level Qualification". www.tlevels.gov.uk. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ "T Levels | Pearson qualifications". qualifications.pearson.com. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ McGuinness, Alan (11 February 2020). "Labour leadership: Sir Keir Starmer promises to keep Jeremy Corbyn's tuition fees stance". Sky News. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ "Labour set to ditch pledge for free university tuition, Starmer says". BBC News. 2 May 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ "Dropping tuition fees pledge will raise questions over how fast Starmer wants change". Sky News. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ "Students pay a heavy price from latest Starmer U-turn say Greens". greenparty.org.uk. Green Party of England and Wales. 3 May 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ "Education". greenparty.org.uk. Green Party of England and Wales. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ Weale, Sally; correspondent, Sally Weale Education (31 May 2023). "Funding model for UK higher education is 'broken', say university VCs". The Guardian.

- ^ Lawford, Melissa (17 December 2023). "The ticking time bomb under Britain's universities". The Telegraph.

- ^ Adams, Richard (19 May 2024). "Next government must make hard university funding decisions, fast". The Guardian.

- ^ "[ZIP file] EoC16 Dataset". UCAS. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017.

- ^ "Participation rates in higher education: 2006 to 2016". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ "Student Support in England:Written statement - HCWS310". UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Overseas Students: EU Nationals Question for Department for Education - UIN 106375, tabled on 20 October 2020 - by Daniel Zeichner - answered by Michelle Donelan". UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ "EU students will be charged more to study at UK universities from 2021". euronews. 24 June 2020. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Undergraduate tuition fees and student loans". UCAS. 20 October 2014. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ Hubble, Sue; Bolton, Paul (2018). Prime Minister's announcement on changes to student funding (PDF). London: House of Commons Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ a b Coughlan, Sean (19 February 2018). "May rules out scrapping tuition fees". BBC News. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "The Government has 'betrayed' students by not revealing something vital in the Autumn Statement". The Independent. 25 November 2015. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ "Consultation on freezing the student loan repayment threshold" (PDF). GOV.UK. Department for Business Innovation & Skills. July 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016.

((cite web)): CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Williams, Rachel; Vasagar, Jeevan (18 November 2010). "University tuition fees hike 'will deter most poorer students' – poll". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2016 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Adams, Richard (12 August 2014). "University tuition fee rise has not deterred poorer students from applying". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ a b "The worst place for poor students in the UK? Scotland". www.newstatesman.com. 8 June 2021. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ a b Robbins, Martin (28 January 2016). "The evidence suggests I was completely wrong about tuition fees". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Murphy, Richard; Scott-Clayton, Judith; Wyness, Gillian (February 2018). "The End of Free College in England: Implications for Quality, Enrolments, and Equity" (PDF). NBER Working Paper No. 23888. doi:10.3386/w23888. S2CID 158643373. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ "Tuition fees". nidirect. 9 December 2015. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ "Repaying your student loan". nidirect. 10 December 2015. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ "Independent /Young (Dependent) Status" (PDF). SAAS. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ "Free university tuition for EU students in Scotland ends". BBC News. 9 July 2020. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Tuition fees in Scotland". Study.eu. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ "Tuition fees for students undertaking a full-time course 2015-2016 and 2016-2017" (PDF). SAAS - The Student Awards Agency for Scotland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2016.

- ^ Kelly, Matthew (24 August 2011). "Does Scotland's university fees system breach human rights laws? | Matthew Kelly". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ "Legal challenge over fees for English students fails". HeraldScotland. 4 February 2013. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ "Extension of free tuition for EU students". Scottish Government News. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ "Scottish Government - Graduate endowment scrapped". Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ "MSPs vote to scrap endowment fee". BBC News. 28 February 2008. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ "Welsh tuition fees to rise by £250 a year from September". BBC News. 6 February 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Students who Started a Course on or After 1 August 2018". www.studentfinancewales.co.uk. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ "Student Finance". Which? Money. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ "Student finance: higher education: Full-time undergraduates". www.gov.wales. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ "Wales unveils means-tested university grants of up to £11,000 a year". the Guardian. 22 November 2016. Archived from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ "Repaying your student loan". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ Jones, Rupert (11 April 2017). "Student loan interest rate set to rise by a third after UK inflation surge". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ Partington, Richard (18 April 2018). "Ministers under fire as student loan interest hits 6.3%". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ "Repaying your student loan". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ "Brexit Party says it will scrap interest on tuition fees". BBC News. 30 June 2019. Archived from the original on 19 November 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ Merrick, Rob (12 August 2019). "Students will owe £8.6bn in loan interest alone within five years, official figures show". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 November 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ Adams, Richard (12 August 2019). "Graduates in England face increasing debt burden, Labour warns". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 November 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ Coughlan, Sean (3 September 2015). "How Germany abolished tuition fees". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 June 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ BMBF, Team Daten-Portal des. "Tabelle 1.9.5 - BMBF Daten-Portal". Daten-Portal des Bundesministeriums für Bildung und Forschung - BMBF (in German). Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ "Opinion: Labour's Tuition Fees policy is a tax cut for the rich, paid for by the poor". Archived from the original on 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Jeremy Corbyn: Scrap tuition fees and give students grants again, says Labour leadership contender". The Independent. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ^ "Reality Check: What would wiping student debt cost?". BBC News. 22 May 2017. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ Adams, Richard (7 July 2017). "Tuition fees should be scrapped, says 'architect' of fees Andrew Adonis". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ Adonis, Andrew (7 July 2017). "I put up tuition fees. It's now clear they have to be scrapped". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ Goodman, A.; Leicester, A.; Reed, H. (2002). "A Graduate Tax for the UK" (PDF). IFS (2002) the Green Budget 2002: 122–130. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015 – via IFS.

External links

- Text of Higher Education Act 2004, which introduced top-up fees

- BBC News Q&A: Student Fees

- The Guardian: All Change (guide to fees)

- Student Loans Company (the body responsible for providing and administering student loans in the UK)

- Dearing Report