| Part of a series on |

| History of religions |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Christianization (or Christianisation) is a term used to describe conversion to Christianity. An individual's Christianization begins when they adopt certain designated beliefs and become part of a community which shares those beliefs. Throughout history, a long list of previously pagan songs, practices, spaces and places have been (voluntarily and involuntarily) Christianized through ritual rededication and redefinition of their purpose or meaning in Christian terms. Christianization occurs in a nation when common lifestyles and community activities reflect some measure of Christian ethics and goals.

Christianization began when the early individual followers of Jesus became itinerant preachers in response to the command recorded in Matthew 28:19, (sometimes called the Great Commission), to go to all the nations of the world and preach the good news about Jesus. [1] It spread through the Roman Empire, Europe of the Middle Ages, and in the twenty-first century, has become a global phenomenon.

Individual conversion

|

Main article: Conversion to Christianity |

James P. Hanigan writes that individual conversion is the foundational experience and the central message of Christianization.[2]: 25 The normative form of Christian conversion begins with an experience of being thrown off balance through cognitive and psychological disequilibrium, followed by an awakening of consciousness and a new awareness of God.[2]: 28–29 Hanigan compares it to "death and rebirth, a turning away..., a putting off of the old..., a change of mind and heart".[2]: 25–26 The person responds by acknowledging and confessing personal lostness and sinfulness, and then accepting a call to holiness thus restoring balance.[2]: 25–28

Baptism

|

Main article: Baptism |

Jesus began his ministry after his baptism by John the Baptist which can be dated to approximately AD 28–35 based on references by the Jewish historian Josephus in his (Antiquities 18.5.2).[3][4][5][6]

Individual conversion is followed by the initiation rite of baptism.[7] In Christianity's earliest communities, candidates for baptism were introduced by someone willing to stand surety for their character and conduct. Baptism created a set of responsibilities within the Christian community.[8] Candidates for baptism were instructed in the major tenets of the faith, examined for moral living, sat separately in worship, were not yet allowed to receive the communion eucharist, but were still generally expected to demonstrate commitment to the community, and obedience to Christ's commands, before being accepted into the community as a full member. This could take months to years.[9]

The normative practice in the ancient church was baptism by immersion of the whole head and body of an adult, with the exception of infants in danger of death, until the fifth or sixth century.[10]: 371 Historian Phillip Schaff has written that sprinkling, or pouring of water on the head of a sick or dying person, where immersion was impractical, was also practiced in ancient times and up through the twelfth century.[11]: 469 Infant baptism was controversial for the Protestant Reformers, but according to Schaff, it was practiced by the ancients and is neither required nor forbidden in the New Testament.[11]: 470

Eucharist

|

Main article: Eucharist |

The celebration of the eucharist (also called communion) was the common unifier for early Christian communities, and remains one of the most important of Christian rituals. Early Christians believed the Christian message, the celebration of communion (the Eucharist) and the rite of baptism came directly from Jesus of Nazareth.[7]

Father Enrico Mazza writes that the "Eucharist is an imitation of the Last Supper" when Jesus gathered his followers for their last meal together the night before he was arrested and killed.[12]: 583 While the majority share the view of Mazza, there are others such as New Testament scholar Bruce Chilton, who argue that there were multiple origins of the Eucharist.[13][12]: 584

In the Middle Ages, the Eucharist came to be understood as a sacrament (wherein God is present) that evidenced Christ's sacrifice, and the prayer given with the rite was to include two strophes of thanksgiving and one of petition. The prayer later developed into the modern version of a narrative, a memorial to Christ and an invocation of the Holy Spirit.[12]: 583

Confirmation

During the Middle Ages, confirmation was added to the rites of initiation.[14]: 1 While baptism, instruction, and Eucharist have remained the essential elements of initiation in all Christian communities,

Some see baptism, confirmation, and first communion as different elements in a unified rite through which one becomes a part of the Christian church. Others consider confirmation a separate rite which may or may not be considered a condition for becoming a fully accepted member of the church in the sense that one is invited to take part in the celebration of the Eucharist. Among those who see confirmation as a separate rite some see it as a sacrament, while others consider it a combination of intercessory prayer and graduation ceremony after a period of instruction.

Temple conversion within Roman Empire

|

Main articles: Christianization of the Roman Empire and Spread of Christianity |

|

Further information: Constantine I and Christianity and Persecution of paganism under Theodosius I |

In Late Antique Roman Empire, sites already consecrated as pagan temples or mithraea began being converted into Christian churches.[38][39] Scholarship has been divided over whether this was a general effort to demolish the pagan past, simple pragmatism, or perhaps an attempt to preserve the past's art and architecture, or most likely, some combination.[40]

R. P. C. Hanson says the direct conversion of temples into churches began in the mid-fifth century but only in a few isolated incidents.[41] According to modern archaeology, 120 pagan temples were converted to churches in the whole of the empire, out of the thousands of temples that existed, with the majority of those conversions dated after the fifth century. It is likely this timing stems from the fact that these buildings and sacred places remained officially in public use, ownership could only be transferred by the emperor, and temples remained protected by law.[42]

In the fourth century, there were no conversions of temples in the city of Rome itself.[43] It is only with the formation of the Papal State in the eighth century, (when the emperor's properties in the West came into the possession of the bishop of Rome), that the conversions of temples in Rome took off in earnest.[44]

According to Dutch historian Feyo L. Schuddeboom, individual temples and temple sites in the city were converted to churches primarily to preserve their exceptional architecture. They were also used pragmatically because of the importance of their location at the center of town.[45]

Christianization of places and practices

|

Main article: Christianized sites |

Christianization has at times involved appropriation, removal and/or redesignation of aspects of native religion and former sacred spaces. This was allowed, or required, or sometimes forbidden by the missionaries involved.[15] The church adapts to its local cultural context, just as local culture and places are adapted to the church, or in other words, Christianization has always worked in both directions: Christianity absorbs from native culture as it is absorbed into it.[16][17]: 177

When Christianity spread beyond Judaea, it first arrived in Jewish diaspora communities.[18] The Christian church was modeled on the synagogue, and Christian philosophers synthesized their Christian views with Semitic monotheism and Greek thought.[19][20] Christianity adopted aspects of Platonic thought, names for months and days of the week – even the concept of a seven-day week – from Roman paganism.[21][22]

Christian art in the catacombs beneath Rome rose out of a reinterpretation of Jewish and pagan symbolism.[23].[24] While many new subjects appear for the first time in the Christian catacombs - i.e. the Good Shepherd, Baptism, and the Eucharistic meal – the Orant figures (women praying with upraised hands) probably came directly from pagan art.[25][26][note 1]

Bruce David Forbes says that "Some way or another, Christmas was started to compete with rival Roman religions, or to co-opt the winter celebrations as a way to spread Christianity, or to baptize the winter festivals with Christian meaning in an effort to limit their [drunken] excesses. Most likely all three".[28] Michelle Salzman has shown that, in the process of converting the Roman Empire's aristocracy, Christianity absorbed the values of that aristocracy.[29]

Some scholars have suggested that characteristics of some pagan gods — or at least their roles — were transferred to Christian saints after the fourth century.[30] Demetrius of Thessaloniki became venerated as the patron of agriculture during the Middle Ages. According to historian Hans Kloft, that was because the Eleusinian Mysteries, Demeter's cult, ended in the 4th century, and the Greek rural population gradually transferred her rites and roles onto the Christian saint Demetrius.[30]

The Roman Empire cannot be considered to have been Christianized before Justinian I in the sixth century.[31] Instead, there was a vigorous public culture shared by polytheists, Jews and Christians alike.[31] By the time a fifth-century pope attempted to denounce the Lupercalia as 'pagan superstition', religion scholar Elizabeth Clark says "it fell on deaf ears".[32] In Historian R. A. Markus's reading of events, this marked a colonialization by Christians of pagan values and practices.[33] For Alan Cameron, the mixed culture that included the continuation of the circuses, amphitheaters and games – sans sacrifice – on into the sixth century involved the secularization of paganism rather than appropriation by Christianity.[34]

Several early Christian writers, including Justin (2nd century), Tertullian, and Origen (3rd century) wrote of Mithraists copying Christian beliefs and practices.[35]

In both Jewish and Roman tradition, genetic families were buried together, but an important cultural shift took place in the way Christians buried one another: they gathered unrelated Christians into a common burial space, as if they really were one family, "commemorated them with homogeneous memorials and expanded the commemorative audience to the entire local community of coreligionists" thereby redefining the concept of family.[36][37]

Temple and icon destruction

During his long reign (307 - 337), Constantine (the first Christian emperor) destroyed a few temples, plundered more, and generally neglected the rest.[46] Classicist Scott Bradbury says Constantine "confiscated temple funds to help finance his own building projects", and he confiscated temple hoards of gold and silver to establish a stable currency; on a few occasions, he confiscated temple land.[47]

In the 300 years prior to the reign of Constantine, Roman authority had confiscated various church properties, some of which were associated with Christian holy places. For example, Christian historians alleged that Hadrian (2nd century) had, in the military colony of Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem), constructed a temple to Aphrodite on the site of the crucifixion of Jesus on Golgotha hill in order to suppress Jewish Christian veneration there.[48] Constantine was vigorous in reclaiming such properties whenever these issues were brought to his attention, and he used reclamation to justify the Aphrodite temple's destruction. Using the vocabulary of reclamation, Constantine acquired several more sites of Christian significance in the Holy Land.[49][50]

In Eusebius' church history, there is a bold claim of a Constantinian campaign to destroy the temples, however, there are discrepancies in the evidence.[51][note 2] Temple destruction is attested to in 43 cases in the written sources, but only four have been confirmed by archaeological evidence.[60] Trombley and MacMullen explain that discrepancies between literary sources and archaeological evidence exist because it is common for details in the literary sources to be ambiguous and unclear.[61] For example, Malalas claimed Constantine destroyed all the temples, then he said Theodisius destroyed them all, then he said Constantine converted them all to churches.[62][63][note 3]

The element of pagan culture most abhorrent to Christians was sacrifice, and altars used for it were routinely smashed. Christians were deeply offended by the blood of slaughtered victims as they were reminded of their own past sufferings associated with such altars.[68]

Additional calculated acts of desecration – removing the hands and feet or mutilating heads and genitals of statues, and "purging sacred precincts with fire" – were acts committed by the common people during the early centuries.[note 4] While seen as 'proving' the impotence of the gods, pagan icons were also seen as having been "polluted" by the practice of sacrifice. They were, therefore, in need of "desacralization" or "deconsecration".[74] Brown says that, while it was in some ways studiously vindictive, it was not indiscriminate or extensive.[75][76] Once temples, icons or statues were detached from 'the contagion' of sacrifice, they were seen as having returned to innocence. Many statues and temples were then preserved as art.[75] Professor of Byzantine history Helen Saradi-Mendelovici writes that this process implies appreciation of antique art and a conscious desire to find a way to include it in Christian culture.[77]

Other sacred sites

Christianizing native religious and cultural activities and beliefs became official in the sixth century. This argument (in favor of what in modern terms is syncretism), is preserved in the Venerable Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum in the form of a letter from Pope Gregory to Mellitus (d.604).[78] L. C. Jane has translated Bede's text:

Tell Augustine that he should by no means destroy the temples of the gods but rather the idols within those temples. Let him, after he has purified them with holy water, place altars and relics of the saints in them. For, if those temples are well built, they should be converted from the worship of demons to the service of the true God. Thus, seeing that their places of worship are not destroyed, the people will banish error from their hearts and come to places familiar and dear to them in acknowledgement and worship of the true God. Bede, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (1.30)

When Benedict moved to Monte Cassino about 530, a small temple with a sacred grove and a separate altar to Apollo stood on the hill. The population was still mostly pagan. The land was most likely granted as a gift to Benedict from one of his supporters. This would explain the authoritative way he immediately cut down the groves, removed the altar, and built an oratory before the locals were converted.[79]

Christianization of the Irish landscape was a complex process that varied considerably depending on local conditions.[80] Ancient sites were viewed with veneration, and were excluded or included for Christian use based largely on diverse local feeling about their nature, character, ethos and even location.[81]

In Greece of the sixth century, the Parthenon, the Erechtheion, and the Theseion were turned into churches, but Alison Frantz has won consensus support of her view that, aside from a few rare instances, temple conversions took place in and after the seventh century, after the displacements caused by the Slavic invasions.[82]

In early Anglo-Saxon England, non-stop religious development meant paganism and Christianity were never completely separate.[83] Lorcan Harney has reported that Anglo-Saxon churches were built by pagan barrows after the 11th century.[84] Richard A. Fletcher suggests that, within the British Isles and other areas of northern Europe that were formerly druidic, there are a dense number of holy wells and holy springs that are now attributed to a saint, often a highly local saint, unknown elsewhere.[85][86] In earlier times many of these were seen as guarded by supernatural forces such as the melusina, and many such pre-Christian holy wells appear to have survived as baptistries.[87]

By 771, Charlemagne had inherited the three-century long conflict with the Saxons who regularly specifically targeted churches and monasteries in brutal raids into Frankish territory.[88] In January 772, Charlemagne retaliated with an attack on the Saxon's most important holy site, a sacred grove in southern Engria.[89] "It was dominated by the Irminsul ('Great Pillar'), which was either a (wooden) pillar or an ancient tree and presumably symbolized Germanic religion's 'Universal Tree'. The Franks cut down the Irminsul, looted the accumulated sacrificial treasures (which the King distributed among his men), and torched the entire grove... Charlemagne ordered a Frankish fortress to be erected at the Eresburg".[90]

Early historians of Scandinavian Christianization wrote of dramatic events associated with Christianization in the manner of political propagandists according to John Kousgärd Sørensen who references the 1987 survey by Birgit Sawyer.[91]: 394 Sørensen focuses on the changes of names, both personal and place names, showing that cultic elements were not banned from personal names and are still in evidence today.[91]: 395–397 Considering place names, large numbers of pre-Christian names survive into the present day demonstrating missionaries had the sense that eradicating elements of the old religion was not necessary.[91]: 400 Indications are that the process of Christianization in Denmark was peaceful and gradual and did not include the complete eradication of the old cultic associations. However, there are local differences as well.[91]: 400, 402

Outside of Scandinavia, old names did not fare as well.[91]: 400–401

The highest point in Paris was known in the pre-Christian period as the Hill of Mercury, Mons Mercuri. Evidence of the worship of this Roman god here was removed in the early Christian period and in the ninth century a sanctuary was built here, dedicated to the 10000 martyrs. The hill was then called Mons Martyrum, the name by which it is still known (Mont Martres) (Longnon 1923, 377; Vincent 1937, 307). San Marino in northern Italy, the shrine of Saint Marino, replaced a pre-Christian cultic name for the place: Monte Titano, where the Titans had been worshipped (Pfeiffer 1980, 79). [The] Monte Giove "Hill of Jupiter" came to be known as San Bernardo, in honour of St Bernhard (Pfeiffer 1980, 79). In Germany an old Wodanesberg "Hill of Ódin" was renamed Godesberg (Bach 1956, 553). Ä controversial but not unreasonable suggestion is that the locality named by Ädam of Bremen as Fosetisland "land of the god Foseti" is to be identified with Helgoland "the holy land", the island off the coast of northern Friesland which, according to Ädam, was treated with superstitious respect by all sailors, particularly pirates (Laur 1960, 360 with refer- ences), [91]: 401

The practice of replacing pagan beliefs and motifs with Christian, and purposefully not recording the pagan history (such as the names of pagan gods, or details of pagan religious practices), has been compared to the practice of damnatio memoriae.[92]

Conversion of nations

|

Main articles: Early Christianity, Acts of the Apostles, Historiography of the Christianization of the Roman Empire, and Christianization of the Roman Empire as diffusion of innovation |

|

See also: Early centers of Christianity § Rome |

Dana L. Robert has written that Christianization across multiple cultures, societies and nations is understandable only through the concept of mission.[17]: 1 Missions, as the embodiment of the Great Commission, are driven by a universalist logic, cannot be equated with western colonialism, but are instead a multi-cultural often complex historical process.[17]: 1

Roman Empire

Christianization without coercion

There is agreement among twenty-first century scholars that Christianization of the Roman Empire in its first three centuries did not happen by imposition.[93] Christianization emerged naturally as the cumulative result of multiple individual decisions and behaviors.[94]

According to historian Michelle Renee Salzman, there is no evidence to indicate that conversion of pagans through force was an accepted method of Christianization at any point in Late Antiquity. Evidence indicates all uses of imperial force concerning religion were aimed at Christian heretics (who were already Christian) such as the Donatists and the Manichaeans and not at non-believers such as Jews or pagans.[95][96][97][98][note 5]

Constantine's role in Christianizing Roman Empire

|

Main article: Historiography of Christianization of the Roman Empire |

The Christianization of the Roman Empire is frequently divided by scholars into the two phases of before and after the conversion of Constantine in 312.[114][note 6] Contemporary scholars are in general agreement that Constantine did not support the suppression of paganism by force.[120][46][121][122] He never engaged in a purge,[123] and there were no pagan martyrs during his reign.[124][125] Pagans remained in important positions at his court.[120] Constantine ruled for 31 years and despite personal animosity toward paganism, he never outlawed paganism.[124][126]

While enduring three centuries of on-again, off-again persecution, from differing levels of government ranging from local to imperial, Christianity had remained 'self-organized' and without central authority.[127] In this manner, it reached an important threshold of success between 150 and 250, when it moved from less than 50,000 adherents to over a million, and became self-sustaining and able to generate enough further growth that there was no longer a viable means of stopping it.[128][129][130][131] Scholars agree there was a significant rise in the absolute number of Christians in the third century.[132]

Making the adoption of Christianity beneficial was Constantine's primary approach to religion, and imperial favor was important to successful Christianization over the next century.[133][134] However, Constantine must have written the laws that threatened and menaced pagans who continued to practice sacrifice. There is no evidence of any of the horrific punishments ever being enacted.[135] There is no record of anyone being executed for violating religious laws before Tiberius II Constantine at the end of the sixth century (574–582).[136] Still, Bradbury notes that the complete disappearance of public sacrifice by the mid-fourth century "in many towns and cities must be attributed to the atmosphere created by imperial and episcopal hostility".[137]

Germanic conversions

|

Further information: Germanic conversions |

Christianization spread through the Roman Empire and neighboring empires in the next few centuries, converting most of the Germanic barbarian peoples who would form the ethnic communities that would become the future nations of Europe. The earliest references to the Christianization of the Germanic peoples are in the writings of Irenaeus (130–202 ), Origen (185-253), and Tertullian (Adv. Jud. VII) (155–220).[138]

- In 341, Romanian born Ulfila (Wulfilas, 311–383) became a bishop and was sent to instruct the Gothic Christians living in Gothia in the province of Dacia.[139][140] Ulfilas is traditionally credited with the voluntary conversion of the Goths between 369 and 372.[141]

- The Vandals converted to Arian Christianity shortly before they left Spain for northern Africa in 429.[142]

- Clovis I converted to Catholicism sometime around 498, extending his kingdom into most of Gaul (France) and large parts of what is now modern Germany.[143]

- The Ostrogothic kingdom, which included all of Italy and parts of the Balkans, began in 493 with the killing of Odoacer by Theodoric. They converted to Arianism.[142]

- Christianization of the central Balkans is documented at the end of the 4th century, where Nicetas the Bishop of Remesiana brought the gospel to "those mountain wolves", the Bessi.[144]

- The Langobardic kingdom, which covered most of Italy, began in 568, becoming Arian shortly after the conversion of Agilulf in 607. Most scholars assert that the Lombards, who had lived in Pannonia and along the Elbe river, converted to Christianity when they moved to Italy in 568, since it was thought they had little to do with the empire before then.[142] According to the Greek scholar Procopius (500-565), the Lombards had "occupied a Roman province for 40 years before moving into Italy". It is now thought that the Lombards first adopted Christianity while still in Pannonia.[142] Procopius writes that, by the time the Lombards moved into Italy, "they appear to have had some familiarity already with both Christianity and some elements of Roman administrative culture".[142][note 7]

Tacitus describes the nature of German religion, and their understanding of the function of a king, as facilitating Christianization.[148] Conversion sometimes took place "top to bottom" in that missionaries aimed at converting Germanic nobility first. A king had divine lineage as a descendant of Woden.[149] Ties of fealty between German kings and their followers often rested on the agreement of loyalty for reward; the concerns of these early societies were communal, not individual; this often produced mass conversions of entire tribes following their king.[150][151] Afterwards, their societies began a gradual process of Christianization that took centuries, with some traces of earlier beliefs remaining.[152]

In all these cases, Christianization meant "the Germanic conquerors lost their native languages. In the remaining parts of the Germanic world, that is, to the North and East of France, the Germanic languages were maintained, but the syntax, the conceptual framework underlying the lexicon, and most of the literary forms were thoroughly latinized".[153]

St. Boniface led the effort in the mid-eighth century to organize churches in the region that would become modern Germany.[154] As ecclesiastical organization increased, so did the political unity of the Germanic Christians. By the year 962, when Pope John XII anoints King Otto I as Holy Roman Emperor, "Germany and Christendom had become one".[154] This union lasted until dissolved by Napoleon in 1806.[154]

Christianization with coercion under Justinian I

Constantine had granted, through the Edict of Milan, the right to all people to follow whatever religion they wished. Also in the West, Emperor Gratian surrendered the title of Pontifex Maximus, the position of head priest of the empire. The religious policy of the Eastern emperor Justinian I (527 to 565) reflected his conviction that a unified Empire presupposed unity of faith.[155][156]

Herrin asserts that, under Justinian, this involved considerable destruction.[157] The decree of 528 had already barred pagans from state office when, decades later, Justinian ordered a "persecution of surviving Hellenes, accompanied by the burning of pagan books, pictures and statues" which took place at the Kynêgion.[157] Herrin says it is difficult to assess the degree to which Christians are responsible for the losses of ancient documents in many cases, but in the mid-sixth century, active persecution in Constantinople destroyed many ancient texts.[157]

According to Anthony Kaldellis, Justinian is often seen as a tyrant and despot.[158] Unlike Constantine, Justinian did purge the bureaucracy of those who disagreed with him.[159][160] He sought to centralize imperial government, became increasingly autocratic, and "nothing could be done", not even in the Church, that was contrary to the emperor's will and command.[161] In Kaldellis' estimation, "Few emperors had started so many wars or tried to enforce cultural and religious uniformity with such zeal".[162][163][164]

Bulgaria

|

Main article: Christianization of Bulgaria |

Christianity had taken root in the Balkans when it was part of the Roman Empire. When the Slavs entered the area and conquered it in the fifth century, they adopted the religion of those they had subdued.[211] In 680, Khan Aspuruk, the leader of an ethnically mixed pagan tribe led an army of Proto-Bulgars across the Danube, conquering the Slavs.[212][213] They settled, and the First Bulgarian Empire was founded in 680/1 with the capitol at Pliska. Over the next two centuries, they fought on and off to protect their borders from various tribes and Byzantium.[214]

Omurtag became Khan in 814. He persecuted Christians, but war with Byzantium, and other wars to acquire territory, brought many Christian prisoners of war into the state. The histories say their faith in the face of extreme misery impressed some of their captors including one of Omurtag's sons who converted. Under Omurtag, Bulgaria and Byzantium maintained a 30-year peace treaty that allowed for more contact, and this increased Christian missionary activities.[215] Christianity spread, while the nobility who were largely Proto-Bulgarians, remained steadfastly pagan.[211]

Official Christianization began in 864/5 under Khan Boris I (852– 889) who had been baptized in 864 in the capital city, Pliska, by Byzantine priests.[216] The need to secure the country's borders, at least from Byzantium, was compounded by the need for internal peace between the different ethnic groups.[217] Boris I determined that imposing Christianity was the answer.[218] The decision was partly military, partly domestic, and partly to diminish the power of the Proto-Bulgarian nobility. A number of nobles reacted violently; 52 were executed.[219] After prolonged negotiations with both Rome and Constantinople, an autocephalous Bulgarian Orthodox Church was formed that used the newly created Cyrillic script to make the Bulgarian language the language of the Church.[220]

Boris' eldest son, Vladimir, also called Rasate, probably ruled from 889 – 893. He was deposed in 893 amidst accusations he was planning to abandon the Christian faith. Scholars remain uncertain as to the veracity of the accusation.[221] His younger brother Symeon, Boris' third son, replaced him, ruling from 893 to 927. He intensified the translation of Greek literature and theology into Bulgarian, and enabled the establishment of an intellectual circle called the school of Preslav.[221] Symeon also led a series of wars against the Byzantines to gain official recognition of his Imperial title and the full independence of the Bulgarian Church. As a result of his victories in 927, the Byzantines finally recognized the Bulgarian Patriarchate.[221]

Serbia

|

Main article: Christianization of Serbs |

Serbs migrated to the Balkan Peninsula between the fifth and seventh centuries. Christianity had been introduced there under Roman rule, but the region had largely returned to paganism by then.[222] Serbian tribes adopted Christianity very slowly. The first instance of mass baptism happened during the reign of Heraclius (610–641) by "elders of Rome" according to Constantine Porphyrogenitus in his annals (r. 913–959).[222]

The full conversion of the Slavs dates to the time of Eastern Orthodox missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius during the reign of the Byzantine emperor Basil I (r. 867–886).[222] The Serbian prince Vlastimir (c. 830 until c. 851) was probably pagan as all his sons had pagan names. In the next generation of Serbian monarchs and nobles there are Petar Gojniković, Stefan Mutimirović, and Pavle Branović.[223] Serbs were baptized sometime before Basil sent imperial admiral Nikita Orifas to Knez Mutimir for aid in the war against the Saracens in 869, after acknowledging the suzerainty of the Byzantine Empire. The fleets and land forces of Zahumlje, Travunia and Konavli (Serbian Pomorje) were sent to fight the Saracens who attacked the town of Ragusa (Dubrovnik) in 869, on the immediate request of Basil I, who was asked by the Ragusians for help.[224]

The first diocese of Serbia, the Diocese of Ras, is mentioned in the ninth century.[222] Its provenance is uncertain, but it was probably founded about 871.[225] Serbia can certainly be seen as a Christian nation by 870.[223]

Serbia was annexed by Bulgaria, becoming a Bulgarian province under Samuel of Bulgaria (997-1014), bringing with it the Cyrillic alphabet and Slav texts.[226] The full Byzantine conquest that followed Samuel's rule did not alter that use of Slavic language and liturgy within the Serbian church.[226]

The medieval Serbian state was created in the second half of the twelfth century.[227]

Croatia

According to Constantine VII, Christianization of Croats began in the 7th century.[228] Viseslav (r. 785–802), one of the first dukes of Croatia, left behind a special baptismal font, which symbolizes the acceptance of the church, and thereby Western culture, by the Croats. The conversion of Croatia is said to have been completed by the time of Duke Trpimir's death in 864. In 879, under duke Branimir, Croatia received papal recognition as a state from Pope John VIII.[229]

The Narentine pirates, based on the Croatian coast, remained pagans until the late ninth century.[230]

Hungarian historian László Veszprémy writes: "By the end of the 11th century, Hungarian expansion had secured Croatia, a country that was coveted by both the Venetian and Byzantine empires and had already adopted the Latin Christian faith. The Croatian crown was held by the Hungarian kings up to 1918, but Croatia retained its territorial integrity throughout. It is not unrelated that the borders of Latin Christendom in the Balkans have remained coincident with the borders of Croatia into present times".[231]

Bohemia/Czech lands

|

Main articles: Christianization of Bohemia and Christianization of Moravia |

What was Bohemia forms much of the Czech Republic, comprising the central and western portions of the country.[232]

Evidence of Christianity in this region north of the Danube can be found dating from the time of Roman occupation in the second century.[233] Christianity was developing organically until the arrival of the Huns in 433 which Christianity survived only to a small extent. From the 7th century, in the territory of contemporary Slovakia, (Great Moravia and its successor state Duchy of Bohemia), Christianization was sustained by the intervention of various missions from the Frankish Empire and Byzantine enclaves in Italy and Dalmatia.[234][235]

Significant missionary activity only took place after Charlemagne defeated the Avar Khaganate several times at the end of the 8th century and beginning of the ninth centuries.[236] A key event with significant influence on the Christianization of Slavs was the elevation of the Salzburg diocese to archdiocese by Charlemagne with permission from the Pope in 798.[237]

The first Christian church of the Western and Eastern Slavs (known to written sources) was built in 828 by Pribina (c. 800–861) ruler and Prince of the Principality of Nitra. His career is recorded in the Conversion of the Bavarians and the Carantanians (a historical work written in 870).[238] Pribina was driven out by Mojmír I in 833.[239] Mojmír was baptized in 831 by Reginhar, Bishop of Passau.[240][241] Despite formal endorsement by the elites, Great Moravian Christianity was described as containing many pagan elements as late as in 852.[241]

Church organization was supervised by the Franks. Prince Rastislav's request for missionaries had been sent to Byzantine Emperor Michael III (842–867) in hopes of establishing a local church organization independent of Frankish clergy.[237][242]

In the Christianization process of Bohemia, Moravia and Slovakia territories, the two Byzantine missionary brothers Saints Constantine-Cyril and Methodius played the key roles beginning in 863.[243] They spent approximately 40 months in Great Moravia continuously translating texts and teaching students.[244] Cyril developed the first Slavic alphabet and translated the Gospel into the Old Church Slavonic language.[242] Old Church Slavonic became the first literary language of the Slavs and, eventually, the educational foundation for all Slavic nations.[244]

In 869 Methodius was consecrated as (arch)bishop of Pannonia and the Great Moravia regions.[244] In 880, Pope John VIII issued the bull Industriae Tuae, by which he set up the independent ecclesiastical province that Rastislav had hoped for, with Archbishop Methodius as its head.[245] The independent archdiocese managed by Methodius was established only for a short time, but relics of this church organization withstood the fall of Great Moravia.[246]

Ireland

|

See also: Hiberno-Scottish mission, Christianization of Ireland, and Celtic Christianity |

Pope Celestine I (422-430) sent Palladius to be the first bishop to the Irish in 431, and in 432, St Patrick began his mission there.[165] Scholars cite many questions (and scarce sources) concerning the next two hundred years.[166] Relying largely on recent archaeological developments, Lorcan Harney has reported to the Royal Academy that the missionaries and traders who came to Ireland in the fifth to sixth centuries were not backed by any military force.[165]

Patrick and Palladius and other British and Gaulish missionaries aimed first at converting royal households. Patrick indicates in his Confessio that safety depended upon it.[167] Communities often followed their king en masse.[167] It is likely most natives were willing to embrace the new religion, and that most religious communities were willing to integrate themselves into the surrounding culture.[168] Conversion and consolidation were long complex processes that took centuries.[165]

Great Britain

|

See also: Anglo-Saxon Christianity and Christianisation of Anglo-Saxon England |

|

Further information: Germanic conversions |

The most likely date for Christianity getting its first foothold in Britain is sometime around 200.[169] Recent archaeology indicates that it had become an established minority faith by the fourth century. It was largely mainstream, and in certain areas, had been continuous.[170]

The conversion of the Anglo-Saxons was begun at about the same time in both the north and south of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in two unconnected initiatives. Irish missionaries led by Saint Columba, based in Iona (from 563), converted many Picts.[171] The court of Anglo-Saxon Northumbria, and the Gregorian mission, who landed in 596, did the same to the Kingdom of Kent. They had been sent by Pope Gregory I and were led by Augustine of Canterbury with a mission team from Italy. In both cases, as in other kingdoms of this period, conversion generally began with the royal family and the nobility adopting the new religion first.[172]

Frankish Empire

|

Main articles: Germanic Christianity and Christianisation of the Germanic peoples |

|

See also: Christianization of the Franks |

The Franks first appear in the historical record in the 3rd century as a confederation of Germanic tribes living on the east bank of the lower Rhine River. Clovis I was the first king of the Franks to unite all of the Frankish tribes under one ruler.[173] According to legend, Clovis had prayed to the Christian god before his battle against one of the kings of the Alemanni, and had consequently attributed his victory to Jesus.[143] The most likely date of his conversion to Catholicism is Christmas Day, 508, following that Battle of Tolbiac.[174][143] He was baptized in Rheims.[175] The Frankish Kingdom became Christian over the next two centuries.[154][note 8]

The conversion of the northern Saxons began with their forced incorporation into the Frankish kingdom in 776 by Charlemagne (r. 768–814). Thereafter, the Saxon's Christian conversion slowly progressed into the eleventh century.[154] Saxons had gone back and forth between rebellion and submission to the Franks for decades.[176] Charlemagne placed missionaries and courts across Saxony in hopes of pacifying the region, but Saxons rebelled again in 782 with disastrous losses for the Franks. In response, the Frankish King "enacted a variety of draconian measures" beginning with the massacre at Verden in 782 when he ordered the decapitation of 4500 Saxon prisoners offering them baptism as an alternative to death.[177] These events were followed by the severe legislation of the Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae in 785 which prescribes death to those that are disloyal to the king, harm Christian churches or its ministers, or practice pagan burial rites.[178] His harsh methods of Christianization raised objections from his friends Alcuin and Paulinus of Aquileia.[179] Charlemagne abolished the death penalty for paganism in 797.[180]

Italy

|

See also: Early centers of Christianity § Rome |

Christianization throughout Italy in Late Antiquity allowed for an amount of religious competition, negotiation, toleration and cooperation; it included syncretism both to and from pagans and Christians; and it allowed for a great deal of secularism.[181] Public sacrifice had largely disappeared by the mid-fourth century, but paganism in a broader sense did not end.[182] Paganism continued, transforming itself over the next two centuries in ways that often included the appropriation and redesignation of Christian practices and ideas while remaining pagan.[183]

In 529, Benedict of Nursia established his first monastery in the Abbey of Monte Cassino, Italy. He wrote the Rule of Saint Benedict based on "pray and work". This "Rule" provided the foundation of the majority of the thousands of monasteries that spread across what is modern day Europe thereby becoming a major factor in the Christianization of Europe. Benedict's biographer Cuthbert Butler writes that "...certainly there will be no demur in recognizing that St. Benedict's Rule has been one of the great facts in the history of western Europe, and that its influence and effects are with us to this day."[184][185][186][187]

Greece

Christianization was slower in Greece than in most other parts of the Roman empire.[188] There are multiple theories of why, but there is no consensus. What is agreed upon is that, for a variety of reasons, Christianization did not take hold in Greece until the fourth and fifth centuries. Christians and pagans maintained a self imposed segregation throughout the period.[82] In Athens, for example, pagans retained the old civic center with its temples and public buildings as their sphere of activity, while Christians restricted themselves to the suburban areas. There was little direct contact between them.[82]

J. M. Speiser has argued that this was the situation throughout the country, and that "rarely was there any significant contact, hostile or otherwise" between Christians and pagans in Greece.[82] This would have slowed the process of Christianization.[189]

Timothy Gregory says, "it is admirably clear that organized paganism survived well into the sixth century throughout the empire and in parts of Greece (at least in the Mani) until the ninth century or later".[15][190] Gregory adds that pagan ideas and forms persisted most in practices related to healing, death, and the family. These are "first-order" concerns – those connected with the basics of life – which were not generally subjected to objections from theologians and bishops.[191]

A seismic moment on the Iberian Peninsula

Hispania had become part of the Roman Republic in the third century BC.[192] In his Epistle to the Romans, the Apostle Paul speaks of his intent to travel there, but when, how, and even if this happened, is uncertain.[193] Paul may have begun the Christianization of Spain, but it may have been begun by soldiers returning from Mauritania.[193] However Christianization began, Christian communities can be found dating to the third century, and bishoprics had been created in León, Mérida and Zeragosa by that same period.[193] In AD 300 an ecclesiastical council held in Elvira was attended by 20 bishops.[194] With the end of persecution in 312, churches, baptistries, hospitals and episcopal palaces were erected in most major towns, and many landed aristocracy embraced the faith and converted sections of their villas into chapels.[194]

In 416, the Germanic Visigoths crossed into Hispania as Roman allies.[195] They converted to Arian Christianity shortly before 429.[142] The Visigothic King Sisebut came to the throne in 612 when the Roman emperor Heraclius surrendered his Spanish holdings.[196] The emperor had received a prophecy that the empire would be destroyed by a circumcised people; lacking awareness of Islam, he applied this to the Jews. Heraclius is said to have called upon Sisebut to banish all Jews who would not submit to baptism. Bouchier says 90,000 Hebrews were baptized while others fled to France or North Africa.[197] This contradicted the traditional position of the Catholic Church on the Jews, and scholars refer to this shift as a "seismic moment" in Christianization.[198]

Despite early Christian testimonies and institutional organization, Christianization of the Basques was slow. Muslim accounts from the period of the Umayyad conquest of Hispania (711 – 718) up to the 9th century, indicate the Basques were not considered Christianized by the Muslims who called them magi or 'pagan wizards', rather than 'People of the Book' as Christians or Jews were.[199]

Armenia, Georgia, Ethiopia and Eritrea

In 301, Armenia became the first kingdom in history to adopt Christianity as an official state religion.[200] The transformations taking place in these centuries of the Roman Empire had been slower to catch on in Caucasia. Indigenous writing did not begin until the fifth century, there was an absence of large cities, and many institutions such as monasticism did not exist in Caucasia until the seventh century.[201] Scholarly consensus places the Christianization of the Armenian and Georgian elites in the first half of the fourth century, although Armenian tradition says Christianization began in the first century through the Apostles Thaddeus and Bartholomew.[202] This is said to have eventually led to the conversion of the Arsacid family, (the royal house of Armenia), through St. Gregory the Illuminator in the early fourth century.[202]

Christianization took many generations and was not a uniform process.[203] Robert Thomson writes that it was not the officially established hierarchy of the church that spread Christianity in Armenia. "It was the unorganized activity of wandering holy men that brought about the Christianization of the populace at large".[204] The most significant stage in this process was the development of a script for the native tongue.[204]

Scholars do not agree on the exact date of Christianization of Georgia, but most assert the early 4th century when Mirian III of the Kingdom of Iberia (known locally as Kartli) adopted Christianity.[205] According to medieval Georgian Chronicles, Christianization began with Andrew the Apostle and culminated in the evangelization of Iberia through the efforts of a captive woman known in Iberian tradition as Saint Nino in the fourth century.[206] Fifth, 8th, and 12th century accounts of the conversion of Georgia reveal how pre-Christian practices were taken up and reinterpreted by Christian narrators.[207]

In 325, the Kingdom of Aksum (Modern Ethiopia and Eritrea) became the second country to declare Christianity as its official state religion.[208]

Europe of the Middle Ages

In Central and Eastern Europe of the 8th and 9th centuries, Christianization began with the aristocracy and was an integral part of the political centralization of the new nations being formed.[209] Bulgaria, Bohemia (which became Czechoslovakia), the Serbs and the Croats, along with Hungary, and Poland, voluntarily joined the Western, Latin church, sometimes pressuring their people to follow. Christianization often took centuries to accomplish. Christianization established schools and spread education, translated Christian writings to local languages, often developing a script to do so, thereby creating the first literature of what had been a pre-literate culture.[210]

Northern crusades and coercion

The Northern Crusades, from 1147 to 1316, form a unique chapter in Christianization. They were largely political, led by local princes against their own enemies for their own gain, and conversion by these princes was almost always a result of armed conquest.[247]

From the days of Charlemagne (747-814), the people around the Baltic Sea had raided – stealing crucial resources, killing, and enslaving captives – from the countries that surrounded them including Denmark, Prussia, Germany and Poland.[248] In the eleventh century, German and Danish nobles united to put a stop to the raiding, in an attempt to force peace through military action, but it didn't last.[249][250]

When the Pope (Blessed) Eugenius III (1145–1153) called for a Second Crusade in response to the fall of Edessa in 1144, Saxon nobles refused to go. They wanted to go back to subduing Baltic Tribes instead.[251] These rulers did not see crusading as a moral, faith based duty as western crusaders did. They saw holy war as a tool for territorial expansion, alliance building, and the empowerment of their own young church and state.[252] Succession struggles would have left them vulnerable at home while they were gone, and the longer pilgrimage could not benefit them with those things that crusading at home would.[253] In 1147, Eugenius' Divini dispensatione, gave the eastern nobles full crusade indulgences to go to the Baltic area instead of the Levant.[251][254][255] The Northern, (or Baltic), Crusades followed, taking place, off and on, with and without papal support, from 1147 to 1316.[256][257][258]

Law professor Eric Christiansen indicates the primary motivation for these wars was the noble's desire for territorial expansion and wealth in the form of land, furs, amber, slaves, and tribute.[259][260][note 9] Taking the time for peaceful conversion did not fit in with these plans.[262] Conversion by these princes was almost always a result of conquest, either by the direct use of force, or indirectly, when a leader converted and required it of his followers.[263]

Monks and priests had to work with the secular rulers on the ruler's terms.[264] According to Fonnesberg-Schmidt, "While the theologians maintained that conversion should be voluntary, there was a widespread pragmatic acceptance of conversion obtained through political pressure or military coercion".[265] Acceptance led some commentators to endorse and approve coerced conversions, something that had not been done in the church before this time.[266][265] Dominican friars helped with this ideological justification by offering a portrayal of the pagans as possessed by evil spirits. In this manner, they could assert that pagans were in need of conquest in order to free them from their terrible circumstance; then they could be peacefully converted.[267][268][269] There were often severe consequences for populations that chose to resist.[270][271][272]

Eastern Europe

In Asia, the combination of Christianization and political centralization created what Peter Brown describes as, "specific micro-Christendoms".[209] It did not only create new states, László Veszprémy says it also created "a new region which later became known as East Central Europe".[273] Conversion began with local elites who wanted to convert because they gained prestige and power through matrimonial alliances and participation in imperial rituals.[209][note 10] Christianization then spread from the center to the edges of society.[209]

Historian Ivo Štefan writes that, "Although Christian authors often depicted the conversion of rulers as the triumph of the new faith, the reality was much more complex. Christianization of everyday life took centuries, with many non-Christian elements surviving in rural communities until the beginning of the modern era".[209]

Poland

|

Main article: Christianization of Poland |

|

See also: Pagan reaction in Poland |

According to historians Franciszek Longchamps de Bérier and Rafael Domingo: "A pre-Christian Poland never existed. Poland entered history suddenly when some western lands inhabited by the Slavs embraced Christianity. Christianity was brought to the region by Dobrawa of Bohemia, the daughter of Boleslaus I the Cruel, Duke of Bohemia, when Duke Mieszko I was baptized and married her in 966." [274] The dynastic interests of the Piasts produced the establishment of both church and state in Great Poland (Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name "Wielkopolska" is a historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań.). That seems to have been a planned strategic decision.[275]

The "Baptism of Poland" (Polish: Chrzest Polski) in 966, refers to the baptism of Mieszko I, the first ruler. "The young Christian state acquired its own Slavic martyr, Wojciech (known as Adalbert), in 1000, plus the archbishopric in Gniezno and four bishoprics (Poznań, Kraków, Wrocław and Kołobrzeg). This Christian state, the earliest attempt at Christianization in this region of Europe, lasted for roughly 70 years".[275] Mieszko's baptism was followed by the building of churches and the establishment of an ecclesiastical hierarchy. Mieszko saw baptism as a way of strengthening his hold on power, with the active support he could expect from the bishops, as well as a unifying force for the Polish people.[275]

Hungary

|

See also: Vata pagan uprising |

Christianity existed in what would become present day Hungary from the time of Roman rule.[276] At the end of the ninth century, the Magyars occupied said territory finding widespread traces of Christianity amongst the Avar tribes, the Bulgars and the Slavs who had previously settled there; there is also historical evidence the Magyar people brought with them a prior knowledge of Christianity.[277]

Around 952, the tribal chief Gyula II of Transylvania, visited Constantinople and was baptized, bringing home with him Hierotheus who was designated bishop of Turkia (Hungary).[278][279] Medieval historian Phyllis G. Jestice writes that Gyula's son-in-law "Géza of Hungary became Duke of the Hungarians [around 970] and began a new open door policy to the west that made mission in that region possible for the first time".[280] Some scholars say Géza used forced conversion, and ruthlessly removed pagan idols and cultic places, but there is little support as Géza is largely excluded from the historical record of Hungary's conversion.[281][282] The conversion of Gyula at Constantinople and the missionary work of Bishop Hierotheus are depicted as leading directly to the court of St. Stephen, the first Hungarian king, a Christian in a still mostly pagan country.[283][284]

While there is historiographical dispute over who actually converted the Hungarian people, King Stephen or the German Emperor Henry II,[285] there is agreement that the realm King Stephen inherited had no established church system, and that monarchy was a break from the "old law".[282] Stephen suppressed rebellion, organized both the Hungarian State (establishing strong royal authority), and the church, by inviting missionaries, and suppressing paganism by making laws requiring the people to attend church every Sunday.[282] Soon the Hungarian Kingdom had two archbishops and 8 bishops, and a defined state structure with province governors that answered to the King. Stephen opened the frontiers of his Kingdom in 1016 to the pilgrims that traveled by land to the Holy Land, and soon this route became extremely popular, being used later in the Crusades. Stephen often personally met pilgrims and invited them to stay in Hungary.[282] Saint Stephen was the first Hungarian monarch elevated to sainthood for his Christian characteristics and not because he suffered a martyr's death.[286]

The beginning of the 11th century marks the end of the first stage of the founding of church and state in Hungary. Hungarian Christianity and the kingdom's ecclesiastical and temporal administrations consolidated towards the end of the 11th century, especially under Ladislas I and Coloman when the feudal order was finally established, the first saints were canonized, and new dioceses were founded.[287]

Kievan Rus'

|

Main article: Christianization of Kievan Rus' |

In 945, Igor, the duke of the Rus', entered a trade agreement with Byzantium in exchange for soldiers, and when those mercenaries returned, they brought Christianity with them.[288] Duchess Olga was the first member of the ruling family to accept baptism, ca. 950 in Constantinople, but it did not spread immediately.[289]

Around 978, Vladimir (978–1015), the son of Sviatoslav, seized power in Kiev.[290] Slavic historian Ivo Štefan writes that, Vladimir examined monotheism for himself, and "Around that same time, Vladimir conquered Cherson in the Crimea, where, according to the Tale of Bygone Years, he was baptized".[289] After returning to Kiev, the same text describes Vladimir as unleashing "a systematic destruction of pagan idols and the construction of Christian churches in their place".[289]

Bohemia, Poland, and Hungary had become part of western Latin Christianity, while the Rus' adopted Christianity from Byzantium, leading them down a different path.[291] A specific form of Rus' Christianity formed quickly.[289] The Rus' dukes maintained exclusive control of the church which was financially dependent upon them.[289] The prince appointed the clergy to positions in government service; satisfied their material needs; determined who would fill the higher ecclesiastical positions; and directed the synods of bishops in the Kievan metropolitanate.[292] This new Christian religious structure was imposed upon the socio-political and economic fabric of the land by the authority of the state's rulers.[293] According to Andrzej Poppe, Slavic historian, it is fully justifiable to call the Church of Rus' a state church. The Church strengthened the authority of the Prince, and helped to justifiy the expansion of Kievan empire into new territories through missionary activity.[292]

Clergy formed a new layer in the hierarchy of society. They taught Christian values, a Christian world view, the intellectual traditions of Antiquity, and translated religious texts into local vernacular language which introduced literacy to all members of the princely dynasty, including women, as well as the populace.[294] Monasteries of the twelfth century became key spiritual, intellectual, art, and craft centers.[295] Under Vladimir's son Yaroslav I the Wise (1016–1018, 1019–1054), a building and cultural boom took place.[295] The Church of Rus' gradually developed into an independent political force in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.[296]

|

Main article: Christianization of Scandinavia |

Before Christianity arrived, there was a common Scandinavian culture with only regional differences. Early Scandinavian loyalties, of the Viking Age (793–1066 AD) and the early medieval period (6th to 10th century), were determined by warfare, temporary treaties, marriage alliances and wealth.[297] Having nothing equivalent to modern borders, kings rose and fell based primarily on their ability to gain wealth for their people.[298]

Christianization of Scandinavia is divided into two stages by Professor of medieval archaeology Alexandra Sanmark.[299] Stage 1 involves missionaries who arrive in pagan territory, on their own, without secular support.[300] This began during the Carolingian era (800s). However, early Scandinavians had been in contact with the Christian world as far back as the Migration Period (AD 375 (possibly as early as 300) to 568), and later during the Viking Age, long before the first documented missions.[301]

Florence Harmer writes that "Between A.D. 960 and 1008 three Scandinavian kings were converted to Christianity". The Danish King Harald Gormsen (Bluetooth) was baptized c. 960. The conversion of Norway was begun by Hákon Aðalsteinsfostri between 935 and 961, but the wide-scale conversion of this kingdom was undertaken by King Olav Tryggvason in c. 995. In Sweden, King Olof Erikson Skötkonung accepted Christianity around 1000.[302][303]

According to Peter Brown, Scandinavians adopted Christianity of their own accord c.1000.[304] Anders Winroth accepts this view, explaining that Iceland became the model for the institutional conversion of the rest of Scandinavia after the farmers voted to adopt Christian law at the Assembly at Thingvellir in AD 1000.[305] Winroth demonstrates that Scandinavians were not passive recipients of the new religion, but were instead converted to Christianity because it was in individual chieftains' political, economic, and cultural interests to do so.[306]

Women were important and influential early converts.[307] Scandinavian women might have found Christianity more appealing than Norse religion for a variety of reasons: Valhalla was unavailable to the majority of women; infanticide of female infants was a common practice, and it was forbidden within Christianity; Christianity had a generally less violent message, and it inserted "gender equality into marriage and sexual relations".[308]

Although Scandinavians became nominally Christian, it would take considerably longer for actual Christian beliefs to establish themselves among the people.[309] Archaeological excavations of burial sites on the island of Lovön near modern-day Stockholm have shown that the actual Christianization of the people was very slow and took at least 150–200 years.[310] Thirteenth-century runic inscriptions from the bustling merchant town of Bergen in Norway show little Christian influence, and one of them appeals to a Valkyrie.[311]

Stage 2 begins when a secular ruler takes charge of Christianization in their territory, and ends when a defined and organized ecclesiastical network is established.[312] For Scandinavia, the emergence of a stable ecclesiastical organization is also marked by closer links with the papacy. Archbishoprics were founded in Lund (1103/04), Nidaros (1153), and Uppsala (1164), and in 1152/3, Cardinal Nicholas Breakspear was sent as a papal legate to Norway and Sweden.[302] By 1350, Scandinavia was an integral part of Western Christendom.[313]

Iberian Reconquista

|

Main article: Reconquista |

Between 711 and 718, the Iberian peninsula had been conquered by Muslims in the Umayyad conquest. Spain and Sicily are the only European regions to have experienced Islamic conquest.[314] The blended Muslim, Christian and Jewish cultures that resulted from the eighth century onward left a profound imprint on Spain.[314]

The centuries long military struggle to reclaim the peninsula from Muslim rule, called the Reconquista, took place until the Christian Kingdoms, that would later become Spain and Portugal, reconquered the Moorish states of Al-Ándalus in 1492 (see: Battle of Covadonga in 722 and the Conquest of Granada in 1492).

Isabel and Ferdinand united the country with themselves as its first royalty quickly establishing the Spanish Inquisition in order to consolidate state interest.[315] The Spanish inquisition was originally authorized by the Pope, yet the initial inquisitors proved so severe that the Pope almost immediately opposed it; to no avail.[316] Ferdinand is said to have pressured the Pope, and in October 1483, a papal bull conceded control of the inquisition to the Spanish crown. According to Spanish historian José Casanova, the Spanish inquisition became the first truly national, unified and centralized state institution.[317] After the 1400s, few Spanish inquisitors were from the religious orders.[318]

Romania

Romania became Christian in a gradual manner beginning when Rome conquered the province of Dacia (106-107). The Romans brought Latinization through intense and massive colonization.[319] Rome withdrew in the third century, then the Slavs reached Dacia in the 6th to 7th centuries and were eventually assimilated.[320] By the 8th to 9th centuries, Romanians existed in a "frontier" on the other side of the Carpathian mountains between Latin, Catholic Europe and the Byzantine, Orthodox East.[321] During most of this period, being Christian allowed its relative observance in parallel with the continued observance of some pagan customs.[322]

Missionaries from south of the Danube moved north spreading their western faith and their Latin language.[323] In the last two decades of the 9th century, missionaries Clement and Naum, (who were disciples of the brothers Cyril and Methodius who had converted the Old Slavic language to a written form in 863), had arrived in the region spreading the Cyrillic alphabet.[320] By the 10th century when the Bulgarian Tsars extended their territory to include Transylvania, they were able to impose the Bulgarian church model and its Slavic language without opposition.[324] Nearly all Romanian words concerning Christian faith have Latin roots, while words regarding the organization of the church are Slavonic.[319]

Romanian historian Ioan-Aurel Pop writes that "Christian fervor and the massive conversion to Christianity among the Slavs may have led to the canonic conversion of the last heathen, or ecclesiastically unorganized, Romanian islands".[320] For Romanians, the church model was "overwhelming, omnipresent, putting pressure on the Romanians and often accompanied by a political element".[320] This ecclesiastical and political tradition continued until the 19th century.[325]

Albania

|

Main article: Church of Caucasian Albania |

Most scholars agree that Christianity was officially adopted in Caucasian Albania in AD 313 or AD 315 when Gregory the Illuminator baptized the Albanian king and ordained the first bishop Tovmas, the founder of the Albanian church. It is highly probable that Christianity covered the whole of antique Caucasian Albania by the late fourth century.[326][327]

The king of the country then was the founder of the Arsacid dynasty of Albania Vachagan I the Brave (but not his grandson Urnayr), and the king of Armenia was Tiridat III the Great, also Arsacid. As M.-L. Chaumont established in 1969, the latter, with the help of Gregory the Illuminator, adopted the Christian faith at the state level in June 311, two months after the publication of the Edict of Sardica “On Tolerance” by Emperor Galerius (293–311). In 313, after the appearance of the Edict of Milan, Tiridat attracted the younger allies of Armenia Iberia-Kartli, Albania-Aluank' and Lazika-Egerk' (Colchis) to the process of Christianization. In the first half of 315, Gregory the Illuminator baptized the Albanian king (who had arrived in Armenia) and ordained the first bishop Tovmas (the founder of the Albanian church, with the center in the capital Kapalak) for his country: he was from the city of Satala in Lesser Armenia. Probably, at the same stage, Christianization covered the whole of antique Albania, i.e. territory north of the Kura River, to the Caspian Sea and the Derbend Pass.[328]

Lithuania

The last of the Baltic crusades was the conflict between the mostly German Teutonic Order and Lithuania in the far northeastern reaches of Europe. Lithuania is sometimes described as "the last pagan nation in medieval Europe".[329]

The Teutonic Order was a crusading organization for the Christian Holy Land founded by members of the Knights Hospitaller. Medieval historian Aiden Lilienfeld says "In 1226, however, the Duke of Mazovia (in modern-day Poland) granted the Order territory in eastern Prussia in exchange for help in subjugating pagan Baltic peoples".[261]

Lilienfeld says "their status as a crusading "monastic" order meant that they could only claim autonomy and legitimacy so long as they could convince the other European Catholic states, from whom they received recruits and financial support, that the Order had a job to do: to convert pagan populations that Catholic rulers perceived to be a threat to Christendom. The greatest of these perceived threats was the Grand Duchy of Lithuania."[261]

Over the course of the next 200 years, the Order expanded its territory to cover much of the eastern Baltic coast.[261]

In 1384, the ten year old daughter of Louis the Great, King of Hungary and Poland, and his wife, Elizabeth of Bosnia, named Jadwiga, was crowned king of Poland. One year later, a marriage was arranged between her and the Grand Duke Jogaila of Lithuania. Jogaila was baptized, married, and crowned king in 1386 beginning the 400 year shared history of Poland and Lithuania.[330] This would seem to obviate the need for the Order's crusade, yet activity against local populations, particularly the Samogition peoples of the eastern Baltic, continued in a frequently brutal manner.[261]

The Teutonic Order eventually fell to Poland-Lithuania in 1525. Lilienfeld says that "After this, the Order's territory was divided between Poland-Lithuania and the Hohenzollern dynasty of Brandenburg, putting an end to the monastic state and the formal Northern Crusade. All of the Order's most powerful cities–Danzig (Gdansk), Elbing (Elblag), Marienburg (Malbork), and Braunsberg (Braniewo)–now fall within Poland in the 21st century, except for Koenigsburg (Kaliningrad) in Russia."[261]

Early colonialism (1500s -1700s)

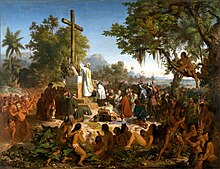

Following the geographic discoveries of the 1400s and 1500s, increasing population and inflation led the emerging nation-states of Portugal, Spain, and France, the Dutch Republic, and England to explore, conquer, colonize and exploit the newly discovered territories.[331] While colonialism was primarily economic and political, it opened the door for Christian missionaries who accompanied the early explorers or soon followed thereby connecting Christianization and colonialism.[332][333]

History also connects Christianization with opposition to colonialism. Historian Lamin Sanneh writes that there is an equal amount of evidence of both missionary support and missionary opposition to colonialism through "protest and resistance both in the church and in politics".[334] In Sanneh's view, missions were "colonialism's Achilles heel, not its shield".[335] According to historical theologian Justo Gonzales, colonialism and missions each sometimes aided and sometimes impeded the other.[336] According to Sanneh, "Despite their role as allies of the empire, missions also developed the vernacular that inspired sentiments of national identity and thus undercut Christianity's identification with colonial rule".[337]

Different state actors created colonies that varied widely.[338] Some colonies had institutions that allowed native populations to reap some benefits. Others became extractive colonies with predatory rule that produced an autocracy with a dismal record.[339]

A catastrophe was wrought upon the Amerindians by contact with Europeans. Old World diseases like smallpox, measles, malaria and many others spread through Indian populations. "In most of the New World 90 percent or more of the native population was destroyed by wave after wave of previously unknown afflictions. Explorers and colonists did not enter an empty land but rather an emptied one".[340]

Portugal and Spain

|

See also: Christianization of Goa |

Under Spanish and Portuguese rule, creating a Christian Commonwealth was the goal of missions. This included a significant role, from the beginning of colonial rule, played by Catholic missionaries.[341]

Portugal practiced extractive colonialism.[342] Early attempts at Christianization were not very successful, and those who had been converted were not well instructed. In the church's view, this led them into "errors and misunderstandings".[343] In December 1560, the Portuguese Inquisition arrived in Goa, India.[344] This was largely the result of the crown's fear that converted Jews were becoming dominant in Goa and might ally with Ottoman Jews to threaten Portuguese control of the spice trade.[345] After 1561 the Inquisition had a practical monopoly over heresy, and its "policy of terror ... was reflected in the approximately 15,000 trials which took place between 1561 and 1812, involving more than 200 death sentences."[346]

The Spanish military was known for its ill-treatment of Amerindians. Spanish missionaries are generally credited with championing efforts to initiate protective laws for the Indians and for working against their enslavement.[347] This led to debate on the nature of human rights.[348] In 16th-century Spain the issue resulted in a crisis of conscience and the birth of modern international law.[349][350]

In words of outrage similar to those earlier missionaries, Junipero Serra wrote of the depredations of the soldiers against Indian women in California in 1770.[351] Following through on missionary complaints, Viceroy Bucareli drew up the first regulatory code of California, the Echeveste Regulations. [352] Missionary opposition and military prosecution failed to protect the Amerindian women.[353] On the one hand, California missionaries sought to protect the Amerindians from exploitation by the conquistadores, soldiers and colonists. On the other hand, Jesuits, Franciscans and other orders relied on corporal punishment and an institutionalized racialism for training the "untamed savages".[354]

France

In the seventeenth century, the French used assimilation as a means of establishing colonies controlled by the state rather than private companies.[355] Within the context of western geocentrism, assimilation (integration of a small group into a larger one) has been used to legitimize European colonization morally and politically for centuries.[356] It advocated multiple aspects of European culture such as "civility, social organization, law, economic development, civil status," dress, bodily description, religion and more to the exclusion of local culture.[357]

Their goal was a political and religious community representative of an ideal society as articulated through the progressive theory of history. This common theory of the time asserts that history shows the normal progression of society is toward constant betterment; that humans could therefore eventually be perfected; that primitive nations could be forced to become modern states wherein that would happen.[358]

This was linked with the emergence of the modern state and was instrumental in the development of racialism as an explanation of the failure of Christianization.[359][360]

The Dutch Republic

The Dutch Reformed church was not a dominant influence in the Dutch colonies.[361] However, the Dutch East Indies Trading Company used assimilation in its Asian port towns, encouraging intermarriage and cultural uniformity, to establish colonies.[362]

Britain

Great Britain's colonial expansion was for the most part driven by commercial ambitions and competition with France.[363] Investors saw converting the natives as a secondary concern.[364] Laura Stevens writes that British missions were more talk than walk.[365] From the beginning, the British talked (and wrote) a great deal about converting native populations, but actual efforts were few and feeble.[365] These missions were universally Protestant, were based on belief in the traditional duty to "teach all nations", the sense of obligation to extend the benefits of Christianity to heathen lands just as Europe itself had been "civilized" centuries before, and a fervent pity for those who had never heard the gospel.[366] Historian Jacob Schacter says "ambivalent benevolence" was at the heart of most British and American attitudes toward Native Americans.[367] The British did not create widespread conversion.[365]

In the United States

|

Main article: History of immigration to the United States |

Colonies in the Americas experienced a distinct type of colonialism called settler colonialism that replaces indigenous populations with a settler society. Settler colonial states include Canada, the United States, Australia, and South Africa.[368]

Missionaries played a crucial role in the acculturation of the Cherokee and other American Indians.[369] A peace treaty with the Cherokee in 1794 stimulated a cultural revival and the welcoming of white missionaries. Historian Mark Noll has written that "what followed was a slow but steady acceptance of the Christian faith".[369] Both Christianization and the Cherokee people received a fatal blow after the discovery of gold in north Georgia in 1828. Cherokee land was seized by the government, and the Cherokee people were transported West in what became known as the Trail of tears.[370]

The history of boarding schools for the indigenous populations in Canada and the US is not generally good. While the majority of native children did not attend boarding school at all, of those that did, recent studies indicate some found happiness and refuge while others found suffering and abuse.[371]

Historian William Gerald McLoughlin has written that, humanitarians who saw the decline of indigenous people with regret, advocated education and assimilation as the native's only hope for survival.[372][373] Over time, many missionaries came to respect the virtues of native culture. "After 1828, most missionaries found it difficult to defend the policies of their government" writes McLoughlin.[372]

The beginning of American Protestant missions abroad followed the sailing of William Carey from England to India in 1793 after the Great awakening.[374]

New imperialism (19th and 20th centuries)

|

Further information: Civilizing mission |

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, New Imperialism was a second wave of colonialism that lasted until World War II.[375] Economists Jan Henryk Pierskalla and Alexander de Juan write that "Early colonial encounters in the Americas of the fifteenth century had little in common with colonization in Africa during the age of the 'New Imperialism'."[376] During this time, colonial powers gained territory at almost three times the rate of the earlier period.[377]