A filibuster or freebooter, in the context of foreign policy, is someone who engages in an (at least nominally) unauthorized military expedition into a foreign country or territory to foment or support a revolution. The term is usually used to describe United States citizens who fomented insurrections in Latin America, particularly in the mid-19th century (Texas, California, Cuba, Nicaragua, Colombia). Filibuster expeditions have also occasionally been used as cover for government-approved deniable operations.

Filibusters are irregular soldiers who (normally) act without official authority from their own government, and are generally motivated by financial gain, political ideology, or the thrill of adventure. The freewheeling actions of the filibusters of the 1850s led to the name being applied figuratively to the political act of filibustering in the United States Congress.[1]

Unlike a mercenary, a filibuster leader/commander works for himself, whilst a mercenary leader works for others.[2]

History

The English term "filibuster" derives from the Spanish filibustero, itself deriving originally from the Dutch vrijbuiter, "privateer, pirate, robber" (also the root of English "freebooter"[3]). The Spanish form entered the English language in the 1850s, as applied to military adventurers from the United States then operating in Central America and the Spanish West Indies.[4]

The Spanish term was first applied to persons raiding Spanish colonies and ships in the West Indies, the most famous of whom was Sir Francis Drake with his 1573 raid on Nombre de Dios. With the end of the era of Caribbean piracy in the early 18th century "filibuster" fell out of general currency.[5]

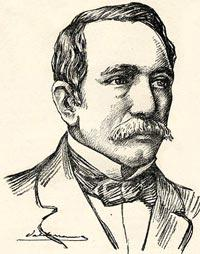

The term was revived in the mid-19th century to describe the actions of adventurers who tried to take control of various Caribbean, Mexican, and Central-American territories by force of arms. In Sonora, Mexico, there were the French Marquis Charles de Pindray and Count Gaston de Raousset-Boulbon and the Americans Joseph C. Morehead and Henry Alexander Crabb. The three most prominent filibusters of that era were Narciso López and John Quitman in Cuba and William Walker in Baja California, Sonora, and lastly Nicaragua. The term returned to American parlance to refer to López's 1851 Cuban expeditions.[6][7]

Several Americans were involved in freelance military schemes, including Aaron Burr, William Blount (West Florida), Augustus W. Magee (Texas), George Mathews (East Florida), George Rogers Clark (Louisiana and Mississippi), William S. Smith (Venezuela), Ira Allen (Canada), William Walker (Mexico and Nicaragua), William A. Chanler (Cuba and Venezuela) and James Long (Texas).[6] Gregor MacGregor was a Scottish filibuster in Florida, Central, and South America.

Although the American public often enjoyed reading about the thrilling adventures of filibusters, Americans involved in filibustering expeditions were usually in violation of the Neutrality Act of 1794 that made it illegal for a citizen to wage war against another country at peace with the United States. For example, the journalist John L. O'Sullivan, who coined the related phrase "Manifest Destiny", was put on trial for raising money for López's failed filibustering expedition in Cuba.

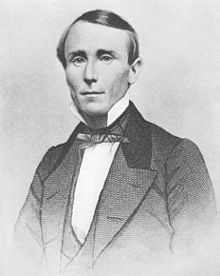

William Walker

In the 1850s, American adventurer William Walker attempted a filibustering campaigns with a strategy involving his leading a private mercenary army. In 1853, he successfully established a short lived republic in the Mexican states of Sonora and Baja California. Later, when a path through Lake Nicaragua was being considered as the possible site of a canal through Central America (see Nicaragua canal), he was hired as a mercenary by one of the factions in a civil war in Nicaragua. He declared himself commander of the country's army in 1856, and soon afterward President of the Republic. After attempting to take control of the rest of Central America and receiving no support from the U.S. government, he was defeated by the four other Central American nations he tried to invade and eventually executed by the local Honduran authorities he tried to overthrow.

In the traditional historiography by historians in both the United States and in Latin America, Walker's filibustering]] represented the high tide of antebellum American imperialism. His brief seizure of Nicaragua in 1855 is typically called a representative expression of Manifest destiny with the added factor of trying to expand slavery into Central America. Historian Michel Gobat, however, presents a strongly revisionist interpretation. He argues that Walker was invited in by Nicaraguan liberals who were trying to force economic modernization and political liberalism. Walker's government comprised those liberals, as well as Yankee colonizers, and European radicals. Walker even included some local Catholics as well as indigenous peoples, Cuban revolutionaries, and local peasants. His coalition was much too complex and diverse to survive long, but it was not the attempted projection of American power, concludes Gobat.[8]

Confederates in exile

After their defeat in the American Civil War, many Confederate Army officers and soldiers, such as Chatham Roberdeau Wheat, of the Louisiana Tigers, obtained valuable military experience from filibuster expeditions. The author Horace Bell served as a major with Walker in Nicaragua in 1856. Colonel Parker H. French served as Minister of Hacienda and was appointed as Minister Plenipotentiary to Washington in 1855.

Fake filibustering by CIA

As part of a proposed 1962 CIA Operation Northwoods to discredit the Fidel Castro regime and provide justification for overt US military operations against Cuba, one of the suggestions was to simulate a Cuban-based, Castro-supported filibuster against a neighboring Caribbean nation. It never happened.[9][additional citation(s) needed]

In the Philippines

In the 19th-century Philippines, the Spanish filibustero gained connotations significantly different from those of the English derivative. The title of the highly influential novel El Filibusterismo by Philippine national hero José Rizal could literally be translated as "filibustering", but could also mean "subversion".

Legacy

William Walker's filibusters are the subject of a poem by Ernesto Cardenal.[10]

See also

- Burr conspiracy

- British Legions

- Hunters' Lodges

- Knights of the Golden Circle

- Foreign Enlistment Act 1870 (UK)

- Vikings

Notes

- ^ William Safire, Safire's New Political Dictionary (2008) p 244

- ^ Axelrod, Alan Mercenaries: A Guide to Private Armies and Private Military Companies CQ Press, 9 January 2014

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, "freebooter". Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, "filibuster". Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ^ Alan Axelrod (2013). Mercenaries: A Guide to Private Armies and Private Military Companies. SAGE. p. 206.

- ^ a b Manifest Destiny's Underworld: Filibustering in Antebellum America, by Robert E. May. Chapter 1 Archived 9 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "the definition of filibuster". www.dictionary.com.

- ^ Michel Gobat, Empire by Invitation: William Walker and Manifest Destiny in Central America (Harvard UP, 2018). See this roundtable evaluation by scholars at H-Diplo.

- ^ http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/news/20010430/northwoods.pdf

- ^ Ernesto Cardenal (1985). Cohen, Jonathan (ed.). With Walker in Nicaragua and other early poems, 1949 - 1954. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. p. 73. ISBN 9780819551238.

References

- Brown, Charles H. Agents of Manifest Destiny: The Lives and Times of the Filibusters. University of North Carolina Press, 1980. ISBN 0-8078-1361-3.

- Lipski, John M. "Filibustero: origin and development." Journal of Hispanic Philology 6, 1982, pp. 213–238

- May, Robert E. "Manifest Destiny's Filibusters" in Sam W. Haynes and Christopher Morris, eds. Manifest Destiny and Empire: American Antebellum Expansionism. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-89096-756-3.

- May, Robert E. Manifest Destiny's Underworld: Filibustering in Antebellum America. University of North Carolina Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8078-2703-7.

- Roche, James Jeffrey. The story of the Filibusters. T. F. Unwin, 1891.

- Schreckengost, Gary. The First Louisiana Special Battalion: Wheat's Tigers in the Civil War. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland and Company, Inc., Publishers, 2008. ISBN 978-0-7864-3202-8.

External links

- Texas A & M Univ. on filibustering

- Latin American studies on the Cuban Filibuster Movement (1849–1856)

- the memory palace podcast episode about filibuster, William Walker.

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.