Title page of 1813 edition | |

| Author | Mrs Rundell |

|---|---|

| Subject | English cooking |

| Genre | Cookery |

| Publisher | John Murray |

Publication date | 1806 |

| Publication place | England |

A New System of Domestic Cookery, first published in 1806 by Maria Rundell, was the most popular English cookery book of the first half of the nineteenth century; it is often referred to simply as Mrs Rundell, but its full title is A New System of Domestic Cookery: Formed Upon Principles of Economy; and Adapted to the Use of Private Families.

Mrs Rundell has been called "the original domestic goddess"[a] and her book "a publishing sensation" and "the most famous cookery book of its time".[1] It ran to over 67 editions; the 1865 edition had grown to 644 pages, and earned two thousand guineas.

The first edition of 1806 was a short collection of Rundell's recipes published by John Murray. It went through dozens of editions, both legitimate and pirated, in both Britain and the United States, where the first edition was published in 1807.[2] The frontispiece typically credited the authorship to "A Lady". Later editions continued for some forty years after Rundell's death. Emma Roberts edited the 64th edition, adding some recipes of her own.[3]

Sales of A New System of Domestic Cookery helped to found the John Murray publishing empire. Sales in Britain were over 245,000; worldwide, over 500,000; the book stayed in print until the 1880s.[1] When Rundell and Murray fell out, she approached a rival publisher, Longman's, leading to a legal battle.[1][4]

The 1865 edition is divided into 35 chapters over 644 pages. It begins with a two-page preface. The table of contents lists each recipe under its chapter heading. There is a set of tables of weights, measures, wages and taxes before the main text. There is a full index at the end.

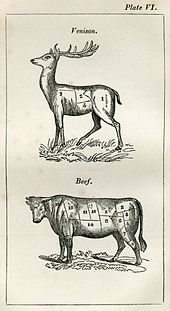

In contrast to the relative disorder of English eighteenth century cookery books such as Eliza Smith's The Compleat Housewife (1727) or Elizabeth Raffald's The Experienced English Housekeeper (1769), Rundell's text is strictly ordered and neatly subdivided. Where those books consist almost wholly of recipes, Mrs Rundell begins by explaining techniques of economy ("A minute account of the annual income and the times of payment should be kept in writing"[5]), how to carve, how to stew, how to season, to "Look clean, be careful and nice in work, so that those who have to eat might look on",[6] how to choose and use steam-kettles and the bain-marie, the meanings of foreign terms like pot-au-feu ("truly the foundation of all good cookery"[7]), all the joints of meat, the "basis of all well-made soups",[8] so it is page 65 before actual recipes begin.

The recipes are written as direct instructions. Quantities, if given, are incorporated in the text. For example, "Gravy to make Mutton eat like Venison" runs:[9]

Pick a very stale woodcock, or snipe, cut it to pieces (but first take out the bag from the entrails), and simmer with as much unseasoned meat gravy as you will want. Strain it, and serve in the dish.[9]

Basic skills like making pastry are explained separately, and then not mentioned in recipes. Under "Pastry", Rundell gives directions for "Rich Puff Paste", "A less rich Paste", and "Crust for Venison Pasty", with variations such as "Raised Crusts for Custards or Fruit".[10] A recipe for "Shrimp Pie, excellent" then proceeds with the bare minimum indication of quantities and a passing mention of "the paste":[11]

Pick a quart of shrimps; if they are very salt, season them with only mace and a clove or two. Mince two or three anchovies; mix these with the spice, and then season the shrimps. Put some butter at the bottom of the dish, and over the shrimps, with a glass of sharp white wine. The paste must be light and thin. They do not take long baking.[11]

Advice is given on choosing the best supplies in the market. For instance:[12]

Fowls.—If a cock is young, his spurs will be short; but take care to see they have not been cut or pared, which is a trick often practised. If fresh, the vent will be close and dark.[12]

The Monthly Review wrote in 1827 that A New System of Domestic Cookery

is almost too well known to require notice [i.e. a review]. Its chief object is, to teach economy in the management of the table; and this, we think, it accomplishes. We cannot speak in praise of its receipts for the higher kinds of cookery, but we dare say that they will be very much admired by precisely that class of gastronomes whose judgement is worth nothing.[13]

The review concluded that "though we have no respect for Mrs. Rundell's salmis, we cordially admire her practical good sense, and applaud her for the production of a useful book" which had been "the pattern of all that have since been published."[13]

By 1841 the Quarterly Literary Advertiser was able to give as the "Opinions of the Press", on the 64th edition, paragraphs of favourable reviews from the Worcestershire Guardian ("the standard work of reference in every private family in English society"), the Hull Advertiser ("most valuable advice upon all household matters"), the Derby Reporter ("a complete guide ... suited to the present advanced state of the art"), Keane's Bath Journal ("it leaves no room to any rival"), the Durham Advertiser ("No housekeeper ought to be without this book"), the Brighton Gazette ("if further proof be wanting, it may be found in the fact that Mrs. Rundell received from her publisher, Mr. Murray, no less a sum than Two Thousand Guineas for her labour!!"), the Aylesbury News ("the peculiarity of the present work is its scientific preface, and an attention to economy as well as taste in giving its directions"), the Bristol Mirror ("far surpasses all its predecessors, and continues to be the best treatise extant concerning the art"), the Midland Counties Herald ("ought to be in the hands of every lady who does not consider it vulgar to look after the affairs of her own household"), the Inverness Herald ("enriched with the latest improvements in gastronomic science") and The Scotsman,[14] which said

The sixty-fourth edition! So much for Mrs. Rundell's portion of the work. Of that portion, after this, we need say nothing. ... Of the additions made by her successor [Emma Roberts], ... she appears to have brought a large amount of experience in the art of cookery to the task, and her name alone is a sufficient guarantee for the utility and excellence of her new receipts.[14]

In 1844, the Foreign Quarterly Review commented on the 67th edition that

it is exclusively a middle class book, and intended for the rich bourgeoisie. The compiler, Mrs. Rundell, had spent the early part of her life in India, and the last edition of the work is enriched with many receipts of Indian cookery. It is on the whole a succinct and judicious compilation... For many years, if report speaks truly, it has produced 1000£. a year to the publisher.[15]

Severin Carrell, writing in The Guardian, calls Rundell "the original domestic goddess" and her book "a publishing sensation" of the early nineteenth century, as it sold "half a million copies and conquered America", as well as helping to found the John Murray publishing empire. For all that, Carrell notes, both "the most famous cookery book of its time" and Rundell herself vanished into obscurity.[1]

Elizabeth Grice, writing in The Daily Telegraph, similarly calls Rundell "a Victorian domestic goddess", though without "Nigella's sexual frisson, or Delia's uncomplicated kitchen manners". Grice points out that "at 61, she was too old to act the pouting goddess" to sell her book, but "sell it did, in vast numbers, as a lifeline to cash-strapped middle-class English households that were desperate to keep up appearances but were having trouble with the staff."[16] She says that compared to Eliza Acton "who could write better" (as in her 1845 book, Modern Cookery for Private Families), and the "ubiquitous" Mrs Beeton, Rundell "has unfairly slipped from view".[16]

Alan Davidson, in the Oxford Companion to Food writes that "It did not include many novel features, although it did have one of the first English recipes for tomato sauce."[16][17]

There have been over 67 editions, success leading to constant revision and extension: the first edition had 344 pages, while the 1865 edition runs to 644 pages including the index. Some landmarks in the book's publication history are: