| Citrus Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Sweet orange (Citrus × sinensis cultivar) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Rutaceae |

| Subfamily: | Aurantioideae |

| Genus: | Citrus L. |

| Species and hybrids | |

|

Ancestral species: Important hybrids: | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Citrus is a genus of flowering trees and shrubs in the family Rutaceae. Plants in the genus produce citrus fruits, including important crops such as oranges, mandarins, lemons, grapefruits, pomelos, and limes.

Citrus is native to South Asia, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Melanesia, and Australia. Indigenous people in these areas have used and domesticated various species since ancient times. Its cultivation first spread into Micronesia and Polynesia through the Austronesian expansion (c. 3000–1500 BCE). Later, it was spread to the Middle East and the Mediterranean (c. 1200 BCE) via the incense trade route, and from to Europe and the Americas.[3][4][5][6]

Renowned for their highly fragrant aromas and complex flavor, citrus are among the most popular fruits in cultivation. With a propensity to hybridize between species, there are numerous varieties of citrus trees encompassing a wide range of appearance and fruit flavors.[7]

History

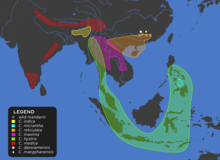

[edit]Citrus plants are native to subtropical and tropical regions of Asia, Island Southeast Asia, Near Oceania, and northeastern and central Australia. Domestication of citrus species involved much hybridization and introgression, leaving much uncertainty about when and where domestication first happened.[3] A genomic, phylogenic, and biogeographical analysis by Wu et al. (2018) has shown that the center of origin of the genus Citrus is likely the southeast foothills of the Himalayas, in a region stretching from eastern Assam, northern Myanmar, to western Yunnan. It diverged from a common ancestor with Poncirus trifoliata. A change in climate conditions during the Late Miocene (11.63 to 5.33 mya) resulted in a sudden speciation event. The species resulting from this event include the citrons (Citrus medica) of South Asia; the pomelos (C. maxima) of Mainland Southeast Asia; the mandarins (C. reticulata), kumquats (C. japonica), mangshanyegan (C. mangshanensis), and ichang papedas (C. cavaleriei) of southeastern China; the kaffir limes (C. hystrix) of Island Southeast Asia; and the biasong and samuyao (C. micrantha) of the Philippines.[3][4]

This was later followed by the spread of citrus species into Taiwan and Japan in the Early Pliocene (5.33 to 3.6 mya), resulting in the tachibana orange (C. tachibana); and beyond the Wallace Line into Papua New Guinea and Australia during the Early Pleistocene (2.5 million to 800,000 years ago), where further speciation events occurred resulting in the Australian limes.[3][4]

The earliest introductions of citrus species by human migrations was during the Austronesian expansion (c. 3000–1500 BCE), where Citrus hystrix, Citrus macroptera, and Citrus maxima were among the canoe plants carried by Austronesian voyagers eastwards into Micronesia and Polynesia.[8]

The citron (Citrus medica) was also introduced early into the Mediterranean basin from India and Southeast Asia. It was introduced via two ancient trade routes: an overland route through Persia, the Levant and the Mediterranean islands; and a maritime route through the Arabian Peninsula and Ptolemaic Egypt into North Africa. Although the exact date of the original introduction is unknown due to the sparseness of archaeobotanical remains, the earliest evidence are seeds recovered from the Hala Sultan Tekke site of Cyprus, dated to around 1200 BCE. Other archaeobotanical evidence include pollen from Carthage dating back to the 4th century BCE; and carbonized seeds from Pompeii dated to around the 3rd to 2nd century BCE. The earliest complete description of the citron was first attested from Theophrastus, c. 310 BCE.[5][6][9] The agronomists of classical Rome made many references to the cultivation of citrus fruits within the limits of their empire.

Lemons, pomelos, and sour oranges are believed to have been introduced to the Mediterranean later by Arab traders at around the 10th century CE; and sweet oranges by the Genoese and Portuguese from Asia during the 15th to 16th century. Mandarins were not introduced until the 19th century.[5][6][9]

Oranges were introduced to Florida by Spanish colonists.[10][11]

In cooler parts of Europe, citrus fruit was grown in orangeries starting in the 17th century; many were as much status symbols as functional agricultural structures.[12]

Etymology

[edit]The generic name originated from Latin, where it referred to either the plant now known as citron (C. medica) or a conifer tree (Thuja). It is related to the ancient Greek word for cedar, κέδρος (kédros). This may be due to perceived similarities in the smell of citrus leaves and fruit with that of cedar.[13] Collectively, Citrus fruits and plants are also known by the Romance loanword agrumes (literally "sour fruits").

Evolution

[edit]The large citrus fruit of today evolved originally from small, edible berries over millions of years. Citrus species began to diverge from a common ancestor about 15 million years ago, at about the same time that Severinia (such as the Chinese box orange) diverged from the same ancestor. About 7 million years ago, the ancestors of Citrus split into the main genus, Citrus, and the genus Poncirus (such as the trifoliate orange), which is closely enough related that it can still be hybridized with all other citrus and used as rootstock. These estimates are made using genetic mapping of plant chloroplasts.[14] A DNA study published in Nature in 2018 concludes that the genus Citrus first evolved in the foothills of the Himalayas, in the area of Assam (India), western Yunnan (China), and northern Myanmar.[15]

The three ancestral (sometimes characterized as "original" or "fundamental") species in the genus Citrus associated with modern Citrus cultivars are the mandarin orange, pomelo, and citron. Almost all of the common commercially important citrus fruits (sweet oranges, lemons, grapefruit, limes, and so on) are hybrids involving these three species with each other, their main progenies, and other wild Citrus species within the last few thousand years.[3][16][17]

Fossil record

[edit]A fossil leaf from the Pliocene of Valdarno (Italy) is described as †Citrus meletensis.[18] In China, fossil leaf specimens of †Citrus linczangensis have been collected from coal-bearing strata of the Bangmai Formation in the Bangmai village, about 10 km (6 miles) northwest of Lincang City, Yunnan. The Bangmai Formation contains abundant fossil plants and is considered to be of late Miocene age. Citrus linczangensis and C. meletensis share some important characters, such as an intramarginal vein, an entire margin, and an articulated and distinctly winged petiole.[19]

Taxonomy

[edit]

The taxonomy and systematics of the genus are complex and the precise number of natural species is unclear, as many of the named species are hybrids clonally propagated through seeds (by apomixis), and genetic evidence indicates that even some wild, true-breeding species are of hybrid origin.

Most cultivated Citrus species seem to be natural or artificial hybrids of a small number of core ancestral species, including the citron, pomelo, mandarin, and papeda.[21] Natural and cultivated citrus hybrids include commercially important fruit such as oranges, grapefruit, lemons, limes, and some tangerines.

Apart from these core citrus species, Australian limes and the recently discovered mangshanyegan are grown. Kumquats and Clymenia spp. are now generally considered to belong within the genus Citrus.[22] Trifoliate orange, which is often used as commercial rootstock, is an outgroup and may or may not be categorized as a citrus.

Phylogenetic analysis suggested the species of Oxanthera from New Caledonia, commonly known as false oranges, should be transferred to the genus Citrus.[23] The transfer has been accepted.[24]

Description

[edit]Tree

[edit]These plants are large shrubs or small to moderate-sized trees, reaching 5–15 m (16–49 ft) tall, with spiny shoots and alternately arranged evergreen leaves with an entire margin.[25] The flowers are solitary or in small corymbs, each flower 2–4 cm (0.79–1.57 in) diameter, with five (rarely four) white petals and numerous stamens; they are often very strongly scented, due to the presence of essential oil glands.

Fruit

[edit]

The fruit is a hesperidium, a specialised berry, globose to elongated,[26] 4–30 cm (1.6–11.8 in) long and 4–20 cm (1.6–7.9 in) diameter, with a leathery rind or "peel" called a pericarp. The outermost layer of the pericarp is an "exocarp" called the flavedo, commonly referred to as the zest. The middle layer of the pericarp is the mesocarp, which in citrus fruits consists of the white, spongy "albedo", or "pith". The innermost layer of the pericarp is the endocarp. The space inside each segment is a locule filled with juice vesicles, or "pulp". From the endocarp, string-like "hairs" extend into the locules, which provide nourishment to the fruit as it develops.[27][28] Many citrus cultivars have been developed to be seedless (see nucellar embryony and parthenocarpy) and easy to peel.[26]

Citrus fruits are notable for their fragrance, partly due to flavonoids and limonoids (which in turn are terpenes) contained in the rind, and most are juice-laden. The juice contains a high quantity of citric acid and other organic acids giving them their characteristic sharp flavour. The genus is commercially important as many species are cultivated for their fruit, which is eaten fresh, pressed for juice, or preserved in marmalades and pickles.

They are also good sources of vitamin C.

The flavonoids include various flavanones and flavones.[29]

Cultivation

[edit]

Citrus trees hybridise very readily – depending on the pollen source, plants grown from a Persian lime's seeds can produce fruit similar to grapefruit. Most commercial citrus cultivation uses trees produced by grafting the desired fruiting cultivars onto rootstocks selected for disease resistance and hardiness.

The colour of citrus fruits only develops in climates with a (diurnal) cool winter.[30] In tropical regions with no winter at all, citrus fruits remain green until maturity, hence the tropical "green oranges".[31] The Persian lime in particular is extremely sensitive to cool conditions, thus it is not usually exposed to cool enough conditions to develop a mature colour.[citation needed] If they are left in a cool place over winter, the fruits will change colour to yellow.

The terms "ripe" and "mature" are usually used synonymously, but they mean different things. A mature fruit is one that has completed its growth phase. Ripening is the changes that occur within the fruit after it is mature to the beginning of decay. These changes usually involve starches converting to sugars, a decrease in acids, softening, and change in the fruit's colour.[32]

Citrus fruits are non-climacteric and respiration slowly declines and the production and release of ethylene is gradual.[33] The fruits do not go through a ripening process in the sense that they become "tree ripe". Some fruits, for example cherries, physically mature and then continue to ripen on the tree. Other fruits, such as pears, are picked when mature, but before they ripen, then continue to ripen off the tree. Citrus fruits pass from immaturity to maturity to overmaturity while still on the tree. Once they are separated from the tree, they do not increase in sweetness or continue to ripen. The only way change may happen after being picked is that they eventually start to decay.

With oranges, colour cannot be used as an indicator of ripeness because sometimes the rinds turn orange long before the oranges are ready to eat. Tasting them is the only way to know whether they are ready to eat.

Citrus trees are not generally frost hardy. Mandarin oranges (C. reticulata) tend to be the hardiest of the common Citrus species and can withstand short periods down to as cold as −10 °C (14 °F), but realistically temperatures not falling below −2 °C (28 °F) are required for successful cultivation. Tangerines, tangors and yuzu can be grown outside even in regions with more marked subfreezing temperatures in winter, although this may affect fruit quality. A few hardy hybrids can withstand temperatures well below freezing, but do not produce quality fruit. Lemons can be commercially grown in cooler-summer/moderate-winter, coastal Southern California, because sweetness is neither attained nor expected in retail lemon fruit. The related trifoliate orange (C. trifoliata) can survive below −20 °C (−4 °F); its fruit are astringent and inedible unless cooked, but a few better-tasting cultivars and hybrids have been developed (see citranges).

The trees thrive in a consistently sunny, humid environment with fertile soil and adequate rainfall or irrigation. Abandoned trees in valleys may suffer, yet survive, the dry summer of Central California's Inner Coast Ranges. At any age, citrus grows well enough with infrequent irrigation in partial shade, but the fruit crop is smaller. Being of tropical and subtropical origin, oranges, like all citrus, are broadleaved and evergreen. They do not drop leaves except when stressed. The stems of many varieties have large sharp thorns. The trees flower in the spring, and fruit is set shortly afterward. Fruit begins to ripen in fall or early winter, depending on cultivar, and develops increasing sweetness afterward. Some cultivars of tangerines ripen by winter. Some, such as the grapefruit, may take up to 18 months to ripen.

Production

[edit]

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, world production of all citrus fruits in 2016 was 124 million metric tons (122,000,000 long tons; 137,000,000 short tons), with about half of this production as oranges.[34] At US $15.2 billion equivalent in 2018, citrus trade[35] makes up nearly half of the world fruit trade, which was US$32.1 billion for the same year.[36] According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), citrus production grew during the early 21st century mainly by the increase in cultivation areas, improvements in transportation and packaging, rising incomes and consumer preference for healthy foods.[34] In 2019–20, world production of oranges was estimated to be 47.5 million metric tons (46,700,000 long tons; 52,400,000 short tons), led by Brazil, Mexico, the European Union, and China as the largest producers.[37]

As ornamental plants

[edit]

Citrus trees grown in tubs and wintered under cover were a feature of Renaissance gardens, once glass-making technology enabled sufficient expanses of clear glass to be produced. An orangery was a feature of royal and aristocratic residences through the 17th and 18th centuries. The Orangerie at the Palace of the Louvre, 1617, inspired imitations that were not eclipsed until the development of the modern greenhouse in the 1840s. In the United States, the earliest surviving orangery is at the Tayloe House, Mount Airy, Virginia. George Washington had an orangery at Mount Vernon.

Some modern hobbyists still grow dwarf citrus in containers or greenhouses in areas where the weather is too cold to grow it outdoors. Consistent climate, sufficient sunlight, and proper watering are crucial if the trees are to thrive and produce fruit. Compared to many of the usual "green shrubs", citrus trees better tolerate poor container care. For cooler winter areas, limes and lemons should not be grown, since they are more sensitive to winter cold than other citrus fruits. Hybrids with kumquats (× Citrofortunella) have good cold resistance. A citrus tree in a container may have to be repotted every 5 years or so, since the roots may form a thick "root-ball" on the bottom of the pot.[38]

Pests and diseases

[edit]

Citrus plants are very liable to infestation by aphids, whitefly, and scale insects (e.g. California red scale). Also rather important are the viral infections to which some of these ectoparasites serve as vectors such as the aphid-transmitted Citrus tristeza virus, which when unchecked by proper methods of control is devastating to citrine plantations. The newest threat to citrus groves in the United States is the Asian citrus psyllid.

The Asian citrus psyllid is an aphid-like insect that feeds on the leaves and stems of citrus trees and other citrus-like plants. The real danger lies in the fact that the psyllid can carry a deadly, bacterial tree disease called Huanglongbing (HLB), also known as citrus greening disease.[39][40] Because as of 2021[update] the causative bacteria are not culturable, evaluation of resistant cultivars and vectors is slow.[39] There are some HLB-resistant and vector-resistant citrus strains known, and genetic engineering and new chemical controls have been proven in laboratory use and show promise for field use.[39]

In August 2005, citrus greening disease was discovered in the south Florida region around Homestead and Florida City. The disease has since spread to every commercial citrus grove in Florida. In 2004–2005, USDA statistics reported the total Florida citrus production to be 169.1 million boxes of fruit. The estimate for all Florida citrus production in the 2015–2016 season is 94.2 million boxes, a 44.3% drop.[41] Carolyn Slupsky, a professor of nutrition and food science at the University of California, Davis has said that "we could lose all fresh citrus within 10 to 15 years".[42]

In June 2008, the psyllid was spotted dangerously close to California – right across the international border in Tijuana, Mexico. Only a few months later, it was detected in San Diego and Imperial Counties, and has since spread to Riverside, San Bernardino, Orange, Los Angeles and Ventura Counties, sparking quarantines in those areas. The Asian citrus psyllid has also been intercepted coming into California in packages of fruit and plants, including citrus, ornamentals, herbs and bouquets of cut flowers, shipped from other states and countries.[40]

The foliage is also used as a food plant by the larvae of Lepidoptera (butterfly and moth) species such as the Geometridae common emerald (Hemithea aestivaria) and double-striped pug (Gymnoscelis rufifasciata), the Arctiidae giant leopard moth (Hypercompe scribonia), H. eridanus, H. icasia and H. indecisa, many species in the family Papilionidae (swallowtail butterflies), and the black-lyre leafroller moth ("Cnephasia" jactatana), a tortrix moth.

Since 2000, the citrus leafminer (Phyllocnistis citrella) has been a pest in California,[43] boring meandering patterns through leaves.

In eastern Australia, the bronze-orange bug (Musgraveia sulciventris) can be a major pest of citrus trees, particularly grapefruit. In heavy infestations it can cause flower and fruit drop and general tree stress.

European brown snails (Cornu aspersum) can be a problem in California, though laying female Khaki Campbell and other mallard-related ducks can be used for control.

Deficiency diseases

[edit]Citrus plants can also develop a deficiency condition called chlorosis, characterized by yellowing leaves[44] highlighted by contrasting leaf veins. The shriveling leaves eventually fall, and if the plant loses too many, it will slowly die. This condition is often caused by an excessively high pH (alkaline soil), which prevents the plant from absorbing iron, magnesium, zinc, or other nutrients it needs to produce chlorophyll. This condition can be cured by adding an appropriate acidic fertilizer formulated for citrus, which can sometimes revive a plant to produce new leaves and even flower buds within a few weeks under optimum conditions. A soil which is too acidic can also cause problems; citrus prefers neutral soil (pH between 6 and 8). Citrus plants are also sensitive to excessive salt in the soil. Soil testing may be necessary to properly diagnose nutrient-deficiency diseases.[45]

Uses

[edit]Culinary

[edit]Many citrus fruits, such as oranges, tangerines, grapefruits, and clementines, are generally eaten fresh.[26] They are typically peeled and can be easily split into segments.[26] Grapefruit is more commonly halved and eaten out of the skin with a spoon.[46] Special spoons (grapefruit spoons) with serrated tips are designed for this purpose. Orange and grapefruit juices are also popular breakfast beverages. More acidic citrus, such as lemons and limes, are generally not eaten on their own. Meyer lemons can be eaten out of hand with the fragrant skin; they are both sweet and sour. Lemonade or limeade are popular beverages prepared by diluting the juices of these fruits and adding sugar. Lemons and limes are also used in cooked dishes, or sliced and used as garnishes. Their juice is used as an ingredient in a variety of dishes; it can commonly be found in salad dressings and squeezed over cooked fish, meat, or vegetables.

A variety of flavours can be derived from different parts and treatments of citrus fruits.[26] The rind and oil of the fruit is generally bitter, especially when cooked, so is often combined with sugar. The fruit pulp can vary from sweet to extremely sour. Marmalade, a condiment derived from cooked orange or lemon, can be especially bitter, but is usually sweetened with sugar to cut the bitterness and produce a jam-like result. Lemon or lime is commonly used as a garnish for water, soft drinks, or cocktails. Citrus juices, rinds, or slices are used in a variety of mixed drinks. The colourful outer skin of some citrus fruits, known as zest, is used as a flavouring in cooking; the white inner portion of the peel, the pith, is usually avoided due to its bitterness. The zest of a citrus fruit, typically lemon or an orange, can also be soaked in water in a coffee filter, and drunk.

-

Wedges of pink grapefruit, lime, and lemon, and a half orange (clockwise from top)

-

Ripe bitter oranges (Citrus × aurantium) from Asprovalta

-

Citrus fruits for sale in a New Zealand supermarket

Phytochemicals and research

[edit]Some Citrus species contain significant amounts of the phytochemical class called furanocoumarins, a diverse family of naturally occurring organic chemical compounds.[47][48] In humans, some (not all) of these chemical compounds act as strong photosensitizers when applied topically to the skin, while other furanocoumarins interact with medications when taken orally. The latter is called the "grapefruit juice effect", a common name for a related group of grapefruit-drug interactions.[47]

Due to the photosensitizing effects of certain furanocoumarins, some Citrus species are known to cause phytophotodermatitis,[49] a potentially severe skin inflammation resulting from contact with a light-sensitizing botanical agent followed by exposure to ultraviolet light. In Citrus species, the primary photosensitizing agent appears to be bergapten,[50] a linear furanocoumarin derived from psoralen. This claim has been confirmed for lime[51][52] and bergamot. In particular, bergamot essential oil has a higher concentration of bergapten (3000–3600 mg/kg) than any other Citrus-based essential oil.[53]

In general, three Citrus ancestral species (pomelos, citrons, and papedas) synthesize relatively high quantities of furanocoumarins, whereas a fourth ancestral species (mandarins) is practically devoid of these compounds.[50] Since the production of furanocoumarins in plants is believed to be heritable, the descendants of mandarins (such as sweet oranges, tangerines, and other small mandarin hybrids) are expected to have low quantities of furanocoumarins, whereas other hybrids (such as limes, grapefruit, and sour oranges) are expected to have relatively high quantities of these compounds.

In most Citrus species, the peel contains a greater diversity and a higher concentration of furanocoumarins than the pulp of the same fruit.[51][52][50] An exception is bergamottin, a furanocoumarin implicated in grapefruit-drug interactions, which is more concentrated in the pulp of certain varieties of pomelo, grapefruit, and sour orange.

One review of preliminary research on diets indicated that consuming citrus fruits was associated with a 10% reduction of risk for developing breast cancer.[54]

List of citrus fruits

[edit]

The genus Citrus has been suggested to originate in the eastern Himalayan foothills. Prior to human cultivation, it consisted of just a few species, though the status of some as distinct species has yet to be confirmed:

- Citrus assamensis – ginger lime, from Assam and Bangladesh

- Citrus crenatifolia – species name is unresolved, from Sri Lanka

- Citrus japonica – kumquats, from East Asia ranging into Southeast Asia (sometimes separated into four-five Fortunella species)

- Citrus mangshanensis – species name is unresolved, from Hunan, China

- Citrus maxima – pomelo (pummelo, shaddock), from the Island Southeast Asia

- Citrus medica – citron, from India

- Citrus reticulata – mandarin orange, from China

- Citrus trifoliata – trifoliate orange, from Korea and adjacent China (often separated as Poncirus)

- Australian limes

- Citrus australasica – Australian finger lime

- Citrus australis – Australian round lime

- Citrus garrawayi – Mount White lime

- Citrus glauca – Australian desert lime

- Citrus gracilis – Kakadu lime or Humpty Doo lime

- Citrus inodora – Russel River lime and Maiden's Australian lime

- Citrus warburgiana – New Guinea wild lime

- Citrus wintersii – Brown River finger lime

- Papedas, including

- Citrus halimii – limau kadangsa, limau kedut kera, from Thailand and Malaya

- Citrus hystrix – Kaffir lime, makrut, from Mainland Southeast Asia to Island Southeast Asia

- Citrus cavaleriei – Ichang papeda from southern China

- Citrus celebica – Celebes papeda

- Citrus indica – Indian wild orange, from the Indian subcontinent[55]

- Citrus latipes – Khasi papeda, from Assam, Meghalaya, Burma[55]

- Citrus longispina – Megacarpa papeda, winged lime, blacktwig lime

- Citrus macrophylla – Alemow

- Citrus macroptera – Melanesian papeda from Indochina to Melanesia[55]

- Citrus micrantha, Citrus westeri – biasong or samuyao from the southern Philippines[56]

- Citrus webberi – Kalpi, Malayan lemon

Hybrids and cultivars

[edit]

Sorted by parentage. As each hybrid is the product of (at least) two parent species, they are listed multiple times.

Citrus maxima-based

- Amanatsu, natsumikan – Citrus × natsudaidai (C. maxima × unknown)

- Cam sành – (C. reticulata × C. × sinensis)

- Dangyuja – (Citrus grandis Osbeck)

- Grapefruit – Citrus × paradisi (C. maxima × C. × sinensis)

- Haruka – Citrus tamurana x natsudaidai

- Hassaku – (Citrus hassaku)

- Ichang lemon – (Citrus wilsonii)

- Imperial lemon – (C. × limon × C. × paradisi)

- Kawachi Bankan – (Citrus kawachiensis)

- Kinnow – (C. × nobilis × C. × deliciosa)

- Kiyomi – (C. × sinensis × C. × unshiu)

- Minneola tangelo – (C. reticulata × C. × paradisi)

- Orangelo, Chironja – (C. × paradisi × C. × sinensis)

- Oroblanco, Sweetie – (C. maxima × C. × paradisi)

- Sweet orange – Citrus × sinensis (probably C. maxima × C. reticulata)

- Tangelo – Citrus × tangelo (C. reticulata × C. maxima or C. × paradisi)

- Tangor – Citrus × nobilis (C. reticulata × C. × sinensis)

- Ugli – (C. reticulata × C. maxima or C. × paradisi)

Citrus medica-based

- Alemow, Colo – Citrus × macrophylla (C. medica × C. micrantha)

- Buddha's hand – Citrus medica var. sarcodactylus, a fingered citron.

- Citron varieties with sour pulp – Diamante citron, Florentine citron, Greek citron and Balady citron

- Citron varieties with sweet pulp – Corsican citron and Moroccan citron

- Etrog, a group of citron cultivars that are traditionally used for a Jewish ritual. Etrog is Hebrew for citron in general.

- Fernandina – Citrus × limonimedica (probably (C. medica × C. maxima) × C. medica)

- Ponderosa lemon – (probably (C. medica × C. maxima) × C. medica)

- Lemon – Citrus × limon (C. medica × C. × aurantium)

- Key lime, Mexican lime, Omani lime – Citrus × aurantiifolia (C. medica × C. micrantha)

- Persian lime, Tahiti lime – C. × latifolia (C. × aurantiifolia × C. × limon)

- Limetta, Sweet Lemon, Sweet Lime, mosambi – Citrus × limetta (C. medica × C. × aurantium)

- Lumia – several distinct pear shaped lemon-like hybrids.

- Pompia – Citrus medica tuberosa Risso & Poiteau, 1818 (C. medica × C. × aurantium), native to Sardinia, genetically synonymous with Rhobs el Arsa.

- Rhobs el Arsa – 'bread of the garden', C. medica × C. × aurantium, from Morocco.

- Yemenite citron – a pulpless true citron.

Citrus reticulata–based

- Bergamot orange – Citrus × bergamia (C. × limon × C. × aurantium)

- Bitter orange, Seville Orange – Citrus × aurantium (C. maxima × C. reticulata)

- Blood orange – Citrus × sinensis cultivars

- Calamansi, Calamondin – (Citrus reticulata × Citrus japonica)

- Cam sành – (C. reticulata × C. × sinensis)

- Chinotto – Citrus × aurantium var. myrtifolia or Citrus × myrtifolia

- ChungGyun – Citrus reticulata cultivar[verification needed]

- Clementine – Citrus × clementina

- Cleopatra Mandarin – Citrus × reshni

- Siranui – Citrus reticulata cv. 'Dekopon' (ChungGyun × Ponkan)

- Daidai – Citrus ×aurantium var. daidai or Citrus × daidai

- Encore – ((Citrus reticulata x sinensis) x C. deliciosa)

- Grapefruit – Citrus ×paradisi (C. maxima × C. × sinensis)

- Hermandina – Citrus reticulata cv. 'Hermandina'

- Imperial lemon – ((C. maxima × C. medica) × C. ×paradisi)

- Iyokan, anadomikan – Citrus × iyo

- Jabara – (Citrus jabara)

- Kanpei – (Citrus reticulata 'Kanpei')

- Kinkoji unshiu – (Citrus obovoidea × unshiu)

- Kinnow, Wilking – (C. × nobilis × C. × deliciosa)

- Kishumikan – (Citrus kinokuni)

- Kiyomi – (C. sinensis × C. × unshiu)

- Kobayashi mikan – (Citrus natsudaidai × unshiu)

- Koji orange – (Citrus leiocarpa)

- Laraha – ''C. × aurantium ssp. currassuviencis

- Mediterranean mandarin, Willow Leaf – Citrus × deliciosa

- Meyer lemon, Valley Lemon – Citrus × meyeri (C. medica × C. × sinensis)

- Michal mandarin – Citrus reticulata cv. 'Michal'

- Mikan, Satsuma – Citrus × unshiu

- Murcott – (C. reticulata x sinensis)

- Naartjie – (C. reticulata × C. nobilis)

- Nova mandarin, Clemenvilla

- Orangelo, Chironja – (C. × paradisi × C. ×s inensis)

- Oroblanco, Sweetie – (C. maxima × C. × paradisi)

- Palestine sweet lime [fr] – Citrus × limettioides Tanaka (C. medica × C. × sinensis)

- Ponkan – Citrus reticulata cv. 'Ponkan'

- Rangpur, Lemanderin, Mandarin Lime – Citrus × limonia (C. reticulata × C. medica)

- Reikou – (Kuchinotsu No.37 x 'Murcott')

- Rough lemon – Citrus × jambhiri Lush. (C. reticulata × C. medica)

- Sanbokan – Citrus sulcata

- Setoka – (Kuchinotsu No.37 x 'Murcott')

- Shekwasha, Hirami Lemon, Taiwan Tangerine – Citrus × depressa

- Sunki, Suenkat – Citrus sunki or C. reticulata var. sunki

- Sweet orange – Citrus × sinensis (C. maxima × C. reticulata)

- Tachibana orange – Citrus tachibana (Mak.) Tanaka or C. reticulata var. tachibana

- Tangelo – Citrus × tangelo (C. reticulata × C. maxima or C. ×paradisi)

- Tangerine – Citrus × tangerina

- Tangor – Citrus × nobilis (C. reticulata × C. ×sinensis)

- Tsunonozomi – ('Kiyomi' × 'Encore')

- Ugli – (C. reticulata × C. maxima or C. ×paradisi)

- Volkamer lemon – Citrus × volkameriana (C. reticulata × C. medica)

- Yukou – (Citrus yuko)

- Yuzu – Citrus × junos (C. reticulata × C. × cavaleriei)

Other/Unresolved

- Djeruk limau – Citrus × amblycarpa

- Gajanimma, Carabao Lime – Citrus × pennivesiculata

- Hyuganatsu, Hyuganatsu pumelo – Citrus tamurana

- Ichang lemon – (C. cavaleriei × C. maxima)

- Kabosu – Citrus ×sphaerocarpa

- Odichukuthi – Citrus Odichukuthi from Malayalam

- Ougonkan – Citrus flaviculpus hort ex. Tanaka

- Sakurajima komikan orange

- Shonan gold – (Ougonkan) Citrus flaviculpus hort ex. Tanaka × (Imamura unshiu), Citrus unshiu Marc

- Sudachi – Citrus × sudachi

For hybrids with kumquats, see citrofortunella. For hybrids with the trifoliate orange, see citrange.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wu, Guohong Albert (7 February 2017). "Genomics of the origin and evolution of Citrus". Nature. 554 (7692): 311–316. Bibcode:2018Natur.554..311W. doi:10.1038/nature25447. hdl:20.500.11939/5741. PMID 29414943. S2CID 205263645.

- ^ "Citrus L.". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Wu GA, Terol J, Ibanez V, López-García A, Pérez-Román E, Borredá C, Domingo C, Tadeo FR, Carbonell-Caballero J, Alonso R, Curk F, Du D, Ollitrault P, Roose ML, Dopazo J, Gmitter FG, Rokhsar DS, Talon M (February 2018). "Genomics of the origin and evolution of Citrus". Nature. 554 (7692): 311–316. Bibcode:2018Natur.554..311W. doi:10.1038/nature25447. hdl:20.500.11939/5741. PMID 29414943.

- ^ a b c d Fuller, Dorian Q.; Castillo, Cristina; Kingwell-Banham, Eleanor; Qin, Ling; Weisskopf, Alison (2017). "Charred pomelo peel, historical linguistics and other tree crops: approaches to framing the historical context of early Citrus cultivation in East, South and Southeast Asia". In Zech-Matterne, Véronique; Fiorentino, Girolamo (eds.). AGRUMED: Archaeology and history of citrus fruit in the Mediterranean (PDF). Publications du Centre Jean Bérard. pp. 29–48. doi:10.4000/books.pcjb.2107. ISBN 9782918887775.

- ^ a b c Zech-Matterne, Véronique; Fiorentino, Girolamo; Coubray, Sylvie; Luro, François (2017). "Introduction". In Zech-Matterne, Véronique; Fiorentino, Girolamo (eds.). AGRUMED: Archaeology and history of citrus fruit in the Mediterranean: Acclimatization, diversification, uses. Publications du Centre Jean Bérard. ISBN 9782918887775.

- ^ a b c Langgut, Dafna (June 2017). "The Citrus Route Revealed: From Southeast Asia into the Mediterranean". HortScience. 52 (6): 814–822. doi:10.21273/HORTSCI11023-16.

- ^ Luro, François; Curk, Franck; Froelicher, Yann; Ollitrault, Patrick (2017). "Recent insights on Citrus diversity and phylogeny". AGRUMED: Archaeology and history of citrus fruit in the Mediterranean. Publications du Centre Jean Bérard. doi:10.4000/books.pcjb.2169. ISBN 978-2-918887-77-5.

- ^ Blench, R.M. (2005). "Fruits and arboriculture in the Indo Pacific region". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 24: 31–50.

- ^ a b Langgut, Dafna (2017). "The history of Citrus medica (citron) in the Near East: Botanical remains and ancient art and texts". In Zech-Matterne, Véronique; Fiorentino, Girolamo (eds.). AGRUMED: Archaeology and history of citrus fruit in the Mediterranean. Publications du Centre Jean Bérard. ISBN 9782918887775.

- ^ "Exploring Florida Documents: Fruit". fcit.usf.edu.

- ^ "History of the Citrus and Citrus Tree Growing in America". www.tytyga.com.

- ^ Billie S. Britz, "Environmental Provisions for Plants in Seventeenth-Century Northern Europe" The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 33.2 (May 1974:133–144) p 133.

- ^ Spiegel-Roy, Pinchas; Eliezer E. Goldschmidt (1996). Biology of Citrus. Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-521-33321-4.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "A phylogenetic analysis of 34 chloroplast genomes elucidates the relationships between wild and domestic species within the genus Citrus". 31 January 2016. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

((cite web)): CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Briggs, Helen (8 February 2018). "DNA Story of when life first gave us lemons". BBC News. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ Velasco, Riccardo; Licciardello, Concetta (2014). "A genealogy of the citrus family". Nature Biotechnology. 32 (7): 640–642. doi:10.1038/nbt.2954. PMID 25004231. S2CID 9357494.

- ^ Inglese, Paolo; Sortino, Giuseppe (2019). "Citrus History, Taxonomy, Breeding, and Fruit Quality". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199389414.013.221. ISBN 9780199389414.

- ^ Citrus meletensis (Rutaceae), a new species from the Pliocene of Valdarno (Italy). Fischer, T.C. & Butzmann, Plant Systematics and Evolution – March 1998, Volume 210, Issue 1, pp 51–55. doi:10.1007/BF00984727

- ^ Citrus linczangensis sp. n., a Leaf Fossil of Rutaceae from the Late Miocene of Yunnan, China by Sanping Xie, Steven R Manchester, Kenan Liu and Bainian Sun – International Journal of Plant Sciences 174(8):1201–1207 October 2013.

- ^ Curk, Franck; Ollitrault, Frédérique; Garcia-Lor, Andres; Luro, François; Navarro, Luis; Ollitrault, Patrick (2016). "Phylogenetic origin of limes and lemons revealed by cytoplasmic and nuclear markers". Annals of Botany. 11 (4): 565–583. doi:10.1093/aob/mcw005. PMC 4817432. PMID 26944784.

- ^ Klein, Joshua D. (2014). "Citron Cultivation, Production and Uses in the Mediterranean Region". Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of the Middle-East. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of the World. Vol. 2. pp. 199–214. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9276-9_10. ISBN 978-94-017-9275-2.

- ^ Andrés García Lor (2013). Organización de la diversidad genética de los cítricos (PDF) (Thesis). p. 79.

- ^ Bayer, R. J., et al. (2009). A molecular phylogeny of the orange subfamily (Rutaceae: Aurantioideae) using nine cpDNA sequences. American Journal of Botany 96(3), 668–85.

- ^ "Oxanthera Montrouz.". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ Del Hotal, Tom. "Citrus Pruning" (PDF). California Rare Fruit Growers.

- ^ a b c d e Janick, Jules (2005). "Citrus". Purdue University Tropical Horticulture Lecture 32. Archived from the original on 24 June 2005. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ "Citrus fruit diagram". ucla.edu. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012.

- ^ "Lith". TheFreeDictionary.com.

- ^ "Flavonoid Composition of Fruit Tissues of Citrus Species". Archived from the original on 28 May 2007. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

((cite journal)): Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "The relation of climate conditions to color development in citrus fruit" (PDF). Retrieved 3 July 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Shailes, Sarah (4 December 2014). "Why is my orange green?". Plant Scientist.

- ^ Helgi Öpik; Stephen A. Rolfe; Arthur John Willis; Herbert Edward Street (2005). The physiology of flowering plants. Cambridge University Press. pp. 309–. ISBN 978-0-521-66251-2. Retrieved 31 July 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Pinchas Spiegel-Roy; Eliezer E. Goldschmidt (1996). Biology of citrus. Cambridge University Press. pp. 101–. ISBN 978-0-521-33321-4. Retrieved 31 July 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Citrus fruit, fresh and processed: Statistical Bulletin" (PDF). UN Food and Agriculture Organization. 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ https://oec.world/en/profile/hs/citrus?disaggregationYearSelector=tradeYear3 OEC — The Observer of Economic Complexity, Citrus

- ^ https://oec.world/en/profile/sitc/fruit OEC — The Observer of Economic Complexity, Fruit

- ^ "Citrus: World Markets and Trade" (PDF). US Department of Agriculture. 1 January 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ Lance., Walheim (1996). Citrus : complete guide to selecting & growing more than 100 varieties for California, Arizona, Texas, the Gulf Coast and Florida. Tucson, Ariz.: Ironwood Press. ISBN 978-0-9628236-4-0. OCLC 34116821.

- ^ a b c Alquézar, Berta; Carmona, Lourdes; Bennici, Stefania; Peña, Leandro (2021). "Engineering of citrus to obtain huanglongbing resistance". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 70. Elsevier: 196–203. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2021.06.003. hdl:10251/189663. ISSN 0958-1669. PMID 34198205. S2CID 235712334.

- ^ a b "About the Asian Citrus Psyllid and Huanglongbing". californiacitrusthreat.org. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ "Florida Citrus Statistics 2015–2016" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture – National Agricultural Statistics Service. 3 October 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ "Farmers, researchers try to hold off deadly citrus greening long enough to find cure". Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ "Citrus Leafminer – UC Pest Management". University of California Agriculture & Natural Resources. January 2019.

- ^ Online at SumoGardener "How to Avoid Yellow Leaves on Citrus Trees". 9 July 2016.

- ^ Mauk, Peggy A.; Tom Shea. "Questions and Answers to Citrus Management (3rd ed.)" (PDF). University of California Cooperative Extension. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ^ Sheu, Scott. "Foods Indigenous to the Western Hemisphere: Grapefruit". American Indian Health and Diet Project. Aihd.ku.edu. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010.

- ^ a b Chen, Meng; Zhou, Shu-yi; Fabriaga, Erlinda; Zhang, Pian-hong; Zhou, Quan (2018). "Food-drug interactions precipitated by fruit juices other than grapefruit juice: An update review". Journal of Food and Drug Analysis. 26 (2): S61–S71. doi:10.1016/j.jfda.2018.01.009. ISSN 1021-9498. PMC 9326888. PMID 29703387.

- ^ Hung, Wei-Lun; Suh, Joon Hyuk; Wang, Yu (2017). "Chemistry and health effects of furanocoumarins in grapefruit". Journal of Food and Drug Analysis. 25 (1): 71–83. doi:10.1016/j.jfda.2016.11.008. ISSN 1021-9498. PMC 9333421. PMID 28911545.

- ^ McGovern, Thomas W.; Barkley, Theodore M. (2000). "Botanical Dermatology". The Electronic Textbook of Dermatology. 37 (5). Internet Dermatology Society. Section Phytophotodermatitis. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00385.x. PMID 9620476. S2CID 221810453. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Dugrand-Judek, Audray; Olry, Alexandre; Hehn, Alain; Costantino, Gilles; Ollitrault, Patrick; Froelicher, Yann; Bourgaud, Frédéric (November 2015). "The Distribution of Coumarins and Furanocoumarins in Citrus Species Closely Matches Citrus Phylogeny and Reflects the Organization of Biosynthetic Pathways". PLOS ONE. 10 (11): e0142757. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1042757D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0142757. PMC 4641707. PMID 26558757.

- ^ a b Nigg, H. N.; Nordby, H. E.; Beier, R. C.; Dillman, A.; Macias, C.; Hansen, R. C. (1993). "Phototoxic coumarins in limes" (PDF). Food Chem Toxicol. 31 (5): 331–35. doi:10.1016/0278-6915(93)90187-4. PMID 8505017.

- ^ a b Wagner, A. M.; Wu, J. J.; Hansen, R. C.; Nigg, H. N.; Beiere, R. C. (2002). "Bullous phytophotodermatitis associated with high natural concentrations of furanocoumarins in limes". Am J Contact Dermat. 13 (1): 10–14. doi:10.1053/ajcd.2002.29948. ISSN 0891-5849. PMID 11887098.

- ^ "Toxicological Assessment of Furocoumarins in Foodstuffs" (PDF). The German Research Foundation (DFG). DFG Senate Commission on Food Safety (SKLM). 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ^ Song, Jung-Kook; Bae, Jong-Myon (1 March 2013). "Citrus fruit intake and breast cancer risk: a quantitative systematic review". Journal of Breast Cancer. 16 (1): 72–76. doi:10.4048/jbc.2013.16.1.72. ISSN 1738-6756. PMC 3625773. PMID 23593085.

- ^ a b c GRIN. "Species list in GRIN for genus Citrus". Taxonomy for Plants. National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland: USDA, ARS, National Genetic Resources Program. Archived from the original on 20 January 2009. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- ^ P. J. Wester (1915), "Citrus Fruits In The Philippines", Philippine Agricultural Review, 8

External links

[edit]- Effects of pollination on Citrus plants Archived 25 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine Pollination of Citrus by Honey Bees

- Citrus Research and Education Center of IFAS (largest citrus research center in world)

- Citrus Variety Collection by the University of California

- Citrus (Mark Rieger, Professor of Horticulture, University of Georgia)

- Fundecitrus – Fund for Citrus Plant Protection is an organization of citrus Brazilian producers and processors.

- Citrus – taxonomy fruit anatomy at GeoChemBio

- Porcher Michel H.; et al. (1995). "Multilingual Multiscript Plant Name Database (M.M.P.N.D) – A Work in Progress". School of Agriculture and Food Systems, Faculty of Land & Food Resources, The University of Melbourne. Australia.