Wordmark used from 1993 to 2007,[a] used for much of Compaq's history as an independent entity | |

Aerial photo of Compaq's headquarters in unincorporated Harris County, Texas (now HP's United States campus) | |

| Compaq | |

| Company type | Public |

| NYSE: CPQ[2] | |

| Industry | Computer hardware Computer software |

| Genre | Computer |

| Founded | February 16, 1982 |

| Founders | Rod Canion Jim Harris Bill Murto |

| Defunct | 2002 (as a separate company) 2013 (as a brand of HP; still active outside of the US) |

| Fate | Acquired by Hewlett-Packard, brand name retired by HP in 2013 |

| Successor | Itself (as a brand of Hewlett-Packard; 2002−2013) Hewlett-Packard/HP Inc.[b] (since 2013) |

| Headquarters | , U.S. |

Area served |

|

| Products | Desktops, laptops, servers, telecom equipment, software |

| Subsidiaries | Tandem Computers Digital Equipment Corporation |

| Website | www |

Compaq Computer Corporation (sometimes abbreviated to CQ prior to the 2007 rebranding) was an American information technology company founded in 1982 that developed, sold, and supported computers and related products and services. Compaq produced some of the first IBM PC compatible computers, being the second company after Columbia Data Products[3] to legally reverse engineer the BIOS of the IBM Personal Computer.[4][5] It rose to become the largest supplier of PC systems during the 1990s before being overtaken by Dell in 2001.[6] Struggling to keep up in the price wars against Dell, as well as with a risky acquisition of DEC,[7] Compaq was acquired for US$25 billion by HP in 2002.[8][9] The Compaq brand remained in use by HP for lower-end systems until 2013 when it was discontinued.[10] Since 2013, the brand is currently licensed to third parties for use on electronics in Brazil and India.[citation needed]

The company was formed by Rod Canion, Jim Harris, and Bill Murto, all of whom were former Texas Instruments senior managers. Murto (SVP of sales) departed Compaq in 1987, while Canion (president and CEO) and Harris (SVP of engineering) left under a shakeup in 1991, which saw Eckhard Pfeiffer appointed president and CEO. Pfeiffer served through the 1990s. Ben Rosen provided the venture capital financing for the fledgling company and served as chairman of the board for 17 years from 1983 until September 28, 2000, when he retired and was succeeded by Michael Capellas, who served as the last chairman and CEO until its merger with HP.[11][12]

Prior to its merger, the company was headquartered in northwest unincorporated Harris County, Texas, which now continues as HP's largest United States facility.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Founding

[edit]

Compaq was founded in February 1982 by Rod Canion, Jim Harris, and Bill Murto, three senior managers from semiconductor manufacturer Texas Instruments. The three of them had left due to lack of faith and loss of confidence in TI's management, and initially considered but ultimately decided against starting a chain of Mexican restaurants.[13][14] Each invested $1,000 to form the company, which was founded with the temporary name Gateway Technology. The name "COMPAQ" was said to be derived from "Compatibility and Quality" but this explanation was an afterthought. The name was chosen from many suggested by Ogilvy & Mather, it being the name least rejected. The first Compaq PC was sketched out on a placemat by Ted Papajohn while dining with the founders in a pie shop,[13][15] (named House of Pies in Houston). Their first venture capital came from Benjamin M. Rosen and Sevin Rosen Funds, who helped the fledgling company secure $1.5 million to produce their initial computer.[16] Overall, the founders managed to raise $25 million from venture capitalists, as this gave stability to the new company as well as providing assurances to the dealers or middlemen.

Unlike many startups, Compaq differentiated its offerings from the many other IBM PC clones by not focusing mainly on price, but instead concentrating on new features, such as portability and better graphics displays as well as performance—and all at prices comparable to those of IBM's PCs. In contrast to Dell and Gateway 2000, Compaq hired veteran engineers with an average of 15 years experience, which lent credibility to Compaq's reputation of reliability among customers.[17][18] Due to its partnership with Intel, Compaq was able to maintain a technological lead in the market place as it was the first one to come out with computers containing the next generation of each Intel processor.[13]

Under Canion's direction, Compaq sold computers only through dealers to avoid potential competition that a direct sales channel would foster, which helped foster loyalty among resellers. By giving dealers considerable leeway in pricing Compaq's offerings, either a significant markup for more profits or discount for more sales, dealers had a major incentive to advertise Compaq.[17][18]

During its first year of sales (second year of operation), the company sold 53,000 PCs for sales of $111 million, the first start-up to hit the $100 million mark that fast. Compaq went public in 1983 on the NYSE and raised $67 million. In 1986, it enjoyed record sales of $329 million from 150,000 PCs, and became the youngest-ever firm to make the Fortune 500. In 1985, sales reached $504 million.[19] In 1987, Compaq hit the $1 billion revenue mark, taking the least amount of time to reach that milestone.[16][17] By 1991, Compaq held the fifth place spot in the PC market with $3 billion in sales that year.[20]

Two key marketing executives in Compaq's early years, Jim D'Arezzo and Sparky Sparks, had come from IBM's PC Group. Other key executives responsible for the company's meteoric growth in the late 1980s and early 1990s were Ross A. Cooley, another former IBM associate, who served for many years as SVP of GM North America; Michael Swavely, who was the company's chief marketing officer in the early years, and eventually ran the North America organization, later passing along that responsibility to Cooley when Swavely retired. In the United States, Brendan A. "Mac" McLoughlin (another long time IBM executive) led the company's field sales organization after starting up the Western U.S. Area of Operations. These executives, along with other key contributors, including Kevin Ellington, Douglas Johns, Steven Flannigan, and Gary Stimac, helped the company compete against the IBM Corporation in all personal computer sales categories, after many predicted that none could compete with the behemoth.

The soft-spoken Canion was popular with employees and the culture that he built helped Compaq to attract the best talent. Instead of headquartering the company in a downtown Houston skyscraper, Canion chose a West Coast-style campus surrounded by forests, where every employee had similar offices and no-one (not even the CEO) had a reserved parking spot. At semi-annual meetings, turnout was high as any employee could ask questions to senior managers.[13][17]

In 1987, company co-founder Bill Murto resigned to study at a religious education program at the University of St. Thomas. Murto had helped to organize the company's marketing and authorized-dealer distribution strategy, and held the post of senior vice president of sales since June 1985. Murto was succeeded by Ross A. Cooley, director of corporate sales. Cooley would report to Michael S. Swavely, vice president for marketing, who was given increased responsibility and the title of vice president for sales and marketing.[21]

Introduction of Compaq Portable

[edit]

In November 1982, Compaq announced their first product, the Compaq Portable, a portable IBM PC compatible personal computer. It was released in March 1983 at $2,995. The Compaq Portable was one of the progenitors of today's laptop; some called it a "suitcase computer" for its size and the look of its case. It was the second IBM PC compatible, being capable of running all software that would run on an IBM PC. It was a commercial success, selling 53,000 units in its first year and generating $111 million in sales revenue. The Compaq Portable was the first in the range of the Compaq Portable series. Compaq was able to market a legal IBM clone because IBM mostly used "off the shelf" parts for their PC. Furthermore, Microsoft had kept the right to license MS-DOS, the most popular and de facto standard operating system[22] for the IBM PC, to other computer manufacturers. The only part which had to be duplicated was the BIOS, which Compaq did legally by using clean room design at a cost of $1 million.[23][24][25]

Unlike other companies, Compaq did not bundle application software with its computers. Vice President of Sales and Service H. L. Sparks said in early 1984:[26]

We've considered it, and every time we consider it we reject it. I don't believe and our dealer network doesn't believe that bundling is the best way to merchandise those products.

You remove the freedom from the dealers to really merchandise when you bundle in software. It is perceived by a lot of people as a marketing gimmick. You know, when you advertise a $3,000 computer with $3,000 worth of free software, it obviously can't be true.

The software should stand on its merits and be supported and so should the hardware. Why should you be constrained to use the software that comes with a piece of hardware? I think it can tend to inhibit sales over the long run.

Compaq instead emphasized PC compatibility, of which Future Computing in May 1983 ranked Compaq as among the "Best" examples.[27] "Many industry observers think [Compaq] is poised for meteoric growth", The New York Times reported in March of that year.[28] By October, when the company announced the Compaq Plus with a 10 MB hard drive, PC Magazine wrote of "the reputation for compatibility it built with its highly regarded floppy disk portable".[29] Compaq computers remained the most compatible PC clones into 1984,[30] and maintained its reputation for compatibility for years,[31] even as clone BIOSes became available from Phoenix Technologies and other companies that also reverse engineered IBM's design, then sold their version to clone manufacturers.

Compaq Deskpro

[edit]On June 28, 1984, Compaq released the Deskpro, a 16-bit desktop computer using an Intel 8086 microprocessor running at 7.14 MHz. It was considerably faster than an IBM PC and was, like the original Compaq Portable, also capable of running IBM software. It was Compaq's first non-portable computer and began the Deskpro line of computers.

Compaq DeskPro 386

[edit]In 1986, Compaq introduced the Deskpro 386, the first PC based on Intel's new 80386 microprocessor.[32][33] Bill Gates of Microsoft later said[34]

the folks at IBM didn't trust the 386. They didn't think it would get done. So we encouraged Compaq to go ahead and just do a 386 machine. That was the first time people started to get a sense that it wasn't just IBM setting the standards, that this industry had a life of its own, and that companies like Compaq and Intel were in there doing new things that people should pay attention to.

The Compaq 386 computer marked the first CPU change to the PC platform that was not initiated by IBM. An IBM-made 386 machine reached the market almost a year later,[32] but by that time Compaq was the 386 supplier of choice and IBM had lost some of its prestige.

For the first three months after announcement, the Deskpro 386 shipped with Windows/386. This was a version of Windows 2.1 adapted for the 80386 processor. Support for the virtual 8086 mode was added by Compaq engineers. (Windows, running on top of the MS-DOS operating system, would not become a popular "operating environment" until at least the release of Windows 3.0 in 1990.)

Compaq SystemPro

[edit]Compaq's technical leadership and the rivalry with IBM was emphasized when the SystemPro server was launched in late 1989 – this was a true server product with standard support for a second CPU and RAID, but also the first product to feature the EISA bus, designed in reaction to IBM's MCA (Micro Channel Architecture) which was incompatible with the original AT bus.

Although Compaq had become successful by being 100 percent IBM-compatible, it decided to continue with the original AT bus—which it renamed ISA[31]—instead of licensing IBM's MCA. Prior to developing EISA Compaq had invested significant resources into reverse engineering MCA, but its executives correctly calculated that the $80 billion already spent by corporations on IBM-compatible technology would make it difficult for even IBM to force manufacturers to adopt the new MCA design. Instead of cloning MCA, Compaq led an alliance with Hewlett Packard and seven other major manufacturers, known collectively as the "Gang of Nine", to develop EISA.[18][31][35]

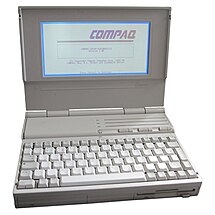

Compaq SLT and LTE

[edit]Development of a truly mobile successor to the Portable line began in 1986, the company releasing two stopgap products in the meantime, the SLT (Compaq's first laptop) and the Compaq Portable III (a lighter-weight, lunchbox-sized entry in the Portable line). In 1989, they introduced the LTE, their first notebook-sized laptop which competed with NEC's UltraLite and Zenith Data Systems's MinisPort. However, whereas the UltraLite and MinisPort failed to gain much uptake due to their novel but nonstandard data storage technologies, the LTE succeeded on account of its use of the conventional floppy drive and spinning hard drive, allowing users to transfer data to and from their desktop computers without any hassle. As well, Compaq began offering docking stations with the release of the LTE/386s in 1990, providing performance comparable to then-current desktop machines.[36] Thus, the LTE was the first commercially successful notebook computer, helping launch the burgeoning industry.[37] It was a direct influence on both Apple and IBM for the development of their own notebook computers, the PowerBook and ThinkPad, respectively.[38][39]

1990s

[edit]By 1989, The New York Times wrote that being the first to release a 80386-based personal computer made Compaq the leader of the industry and "hurt no company more - in prestige as well as dollars - than" IBM.[32] The company was so influential that observers and its executives spoke of "Compaq compatible". InfoWorld reported that "In the [ISA market] Compaq is already IBM's equal in being seen as a safe bet", quoting a sell-side analyst describing it as "now the safe choice in personal computers". Even rival Tandy Corporation acknowledged Compaq's leadership, stating that within the Gang of Nine "when you have 10 people sit down before a table to write a letter to the president, someone has to write the letter. Compaq is sitting down at the typewriter".[31]

Ouster of co-founders

[edit]Michael S. Swavely, president of Compaq's North American division since May 1989, took a six-month sabbatical in January 1991 (which would eventually become retirement effective on July 12, 1991). Eckhard Pfeiffer, then president of Compaq International, was named to succeed him. Pfeiffer also received the title of chief operating officer, with responsibility for the company's operations on a worldwide basis, so that Canion could devote more time to strategy.[40] Swavely's abrupt departure in January led to rumors of turmoil in Compaq's executive suite, including friction between Canion and Swavely, likely as Swavely's rival Pfeiffer had received the number two leadership position. Swavely's U.S. marketing organization was losing ground with only 4% growth for Compaq versus 7% in the market, likely due to short supplies of the LTE 386s from component shortages, rivals that undercut Compaq's prices by as much as 35%, and large customers who did not like Compaq's dealer-only policy.[41] Pfeiffer became president and CEO of Compaq later that year, as a result of a boardroom coup led by board chairman Ben Rosen that forced co-founder Rod Canion to resign as president and CEO.[42]

Pfeiffer had joined Compaq from Texas Instruments, and established operations from scratch in both Europe and Asia. Pfeiffer was given US$20,000 to start up Compaq Europe[43] He started up Compaq's first overseas office in Munich in 1984. By 1990, Compaq Europe was a $2 billion business and number two behind IBM in that region, and foreign sales contributed 54 percent of Compaq's revenues.[44][45] Pfeiffer, while transplanting Compaq's U.S. strategy of dealer-only distribution to Europe, was more selective in signing up dealers than Compaq had been in the U. S. such that European dealers were more qualified to handle its increasingly complex products.[41]

During the 1980s, under Canion's direction Compaq had focused on engineering, research, and quality control, producing high-end, high-performance machines with high profit margins that allowed Compaq to continue investing in engineering and next-generation technology. This strategy was successful as Compaq was considered a trusted brand, while many other IBM clones were untrusted due to being plagued by poor reliability. However, by the end of the eighties many manufacturers had improved their quality and were able to produce inexpensive PCs with off-the-shelf components, incurring none of the R&D costs which allowed them to undercut Compaq's expensive computers.[13] Faced with lower-cost rivals such as Dell, AST Research, and Gateway 2000, Compaq suffered a $71 million loss for that quarter, their first loss as a company, while the stock had dropped by over two-thirds.[46][47] An analyst stated that "Compaq has made a lot of tactical errors in the last year and a half. They were trend-setters, now they are lagging". Canion initially believed that the 1990s recession was responsible for Compaq's declining sales but insisted that they would recover once the economy improved, however Pfeiffer's observation of the European market noted that it was competition as rivals could match Compaq at a fraction of the cost. Under pressure from Compaq's board to control costs as staff was ballooning at their Houston headquarters despite falling U.S. sales, while the number of non-U.S. employees had stayed constant, Compaq made its first-ever layoffs (1400 employees which was 12% of its workforce) while Pfeiffer was promoted to EVP and COO.[13]

Rosen and Canion had disagreed about how to counter the cheaper Asian PC imports, as Canion wanted Compaq to build lower cost PCs with components developed in-house in order to preserve Compaq's reputation for engineering and quality, while Rosen believed that Compaq needed to buy standard components from suppliers and reach the market faster. While Canion developed an 18-month plan to create a line of low-priced computers, Rosen sent his own Compaq engineering team to Comdex without Canion's knowledge and discovered that a low-priced PC could be made in half the time and at lower cost than Canion's initiative.[13][48] It was also believed[by whom?] that Canion's consensus-style management slowed the company's ability to react in the market, whereas Pfeiffer's autocratic style would be suited to price and product competition.[43]

Rosen initiated a 14-hour board meeting, and the directors also interviewed Pfeiffer for several hours without informing Canion. At the conclusion, the board was unanimous in picking Pfeiffer over Canion. As Canion was popular with company workers, 150 employees staged an impromptu protest with signs stating "We love you, Rod." and taking out a newspaper ad saying "Rod, you are the wind beneath our wings. We love you."[17] Canion declined an offer to remain on Compaq's board[45] and was bitter about his ouster as he did not speak to Rosen for years, although their relationship became cordial again. In 1999, Canion admitted that his ouster was justified, saying "I was burned out. I needed to leave. He [Rosen] felt I didn't have a strong sense of urgency". Two weeks after Canion's ouster, five other senior executives resigned, including remaining company founder James Harris as SVP of Engineering. These departures were motivated by an enhanced severance or early retirement, as well as an imminent demotion as their functions were to be shifted to vice presidents.[49]

Market ascension

[edit]

Under Pfeiffer's tenure as chief executive, Compaq entered the retail computer market with the Compaq Presario as one of the first manufacturers in the mid-1990s to market a sub-$1000 PC. In order to maintain the prices it wanted, Compaq became the first first-tier computer manufacturer to utilize CPUs from AMD and Cyrix. The two price wars resulting from Compaq's actions ultimately drove numerous competitors from the market, such as Packard Bell and AST Research. From third place in 1993, Compaq had overtaken Apple Computer and even surpassed IBM as the top PC manufacturer in 1994, as both IBM and Apple were struggling considerably during that time.[50] Compaq's inventory and gross margins were better than that of its rivals which enabled it to wage the price wars.[46][51]

Compaq had decided to make a foray into printers in 1989, and the first models were released to positive reviews in 1992. However, Pfeiffer saw that the prospects of taking on market leader Hewlett-Packard (who had 60% market share) was tough, as that would force Compaq to devote more funds and people to that project than originally budgeted. Compaq ended up selling the printer business to Xerox and took a charge of $50 million.[13][52]

In 1994, Compaq formed a joint venture with ADI Corporation, a Taiwanese manufacturer who produced the bulk of Compaq's monitors, to raise multiple factories in Mexico, Brazil, and Europe to assemble and store ADI's monitors.[53] Compaq sold many of the monitors that they offered to customers of their Deskpro and Presario lines as standalone units to third-party resellers, including their popular 171FS monitor.[54][55]

On June 26, 1995, Compaq reached an agreement with Cisco Systems, Inc., in order to get into networking, including digital modems, routers, and switches favored by small businesses and corporate departments, which was now a $4 billion business and the fastest-growing part of the computer hardware market. Compaq also built up a network engineering and marketing staff.[52]

Management shuffle

[edit]In 1996, despite record sales and profits at Compaq, Pfeiffer initiated a major management shakeup in the senior ranks.[56] John T. Rose, who previously ran Compaq's desktop PC division, took over the corporate server business from SVP Gary Stimac who had resigned. Rose had joined Compaq in 1993 from Digital Equipment Corporation where he oversaw the personal computer division and worldwide engineering, while Stimac had been with Compaq since 1982 and was one of the longest-serving executives. Senior Vice-president for North America Ross Cooley announced his resignation effective at the end of 1996. CFO Daryl J. White, who joined the company in January, 1983 resigned in May, 1996 after 8 years as CFO. Michael Winkler, who joined Compaq in 1995 to run its portable computer division, was promoted to general manager of the new PC products group.[57][58] Earl Mason, hired from Inland Steel effective in May 1996, immediately made an impact as the new CFO. Under Mason's guidance, Compaq utilized its assets more efficiently instead of focusing just on income and profits, which increased Compaq's cash from $700 million to nearly $5 billion in one year. Additionally, Compaq's return on invested capital (after-tax operating profit divided by operating assets) doubled to 50 percent from 25 percent in that period.[46]

Compaq had been producing the PC chassis at its plant in Shenzhen, China to cut costs. In 1996, instead of expanding its own plant, Compaq asked a Taiwanese supplier to set up a new factory nearby to produce the mechanicals, with the Taiwanese supplier owning the inventory until it reached Compaq in Houston.[58] Pfeiffer also introduced a new distribution strategy, to build PCs made-to-order which would eliminate the stockpile of computers in warehouses and cut the components inventory down to two weeks, with the supply chain from supplier to dealer linked by complex software.[57]

Vice-president for Corporate Development Kenneth E. Kurtzman assembled five teams to examine Compaq's businesses and assess each unit's strategy and that of key rivals. Kurtzman's teams recommended to Pfeiffer that each business unit had to be first or second in its market within three years—or else Compaq should exit that line. Also, the company should no longer use profits from high-margin businesses to carry marginally profitable ones, as instead each unit must show a return on investment.[58] Pfeiffer's vision was to make Compaq a full-fledged computer company, moving beyond its main business of manufacturing retail PCs and into the more lucrative business services and solutions that IBM did well at, such as computer servers which would also require more "customer handholding" from either the dealers or Compaq staff themselves.[57] Unlike IBM and HP, Compaq would not build up field technicians and programmers in-house as those could be costly assets, instead Compaq would leverage its partnerships (including those with Andersen Consulting and software maker SAP) to install and maintain corporate systems. This allowed Compaq to compete in the "big-iron market" without incurring the costs of running its own services or software businesses.[59]

Most of Compaq's server sales were for systems that would be running Microsoft's Windows NT operating system, and indeed Compaq was the largest hardware supplier for Windows NT.[60] However, some 20 percent of Compaq servers went for systems that would be running the Unix operating system.[60] This was exemplified by a strategic alliance formed in 1997 between Compaq and the Santa Cruz Operation (SCO), which was known for its server Unix operating system products on Intel-architecture-based hardware.[60] Compaq was also the largest hardware supplier for SCO's Unix products,[60] and some 10 percent of Compaq's ProLiant servers ran SCO's UnixWare.[61]

In January 1998, Compaq was at its height. CEO Pfeiffer boldly predicted that the Microsoft/Intel "Wintel" duopoly would be replaced by "Wintelpaq".

Acquisitions

[edit]Pfeiffer also made several major and some minor acquisitions. In 1997, Compaq bought Tandem Computers, known for their NonStop server line.[62] This acquisition instantly gave Compaq a presence in the higher end business computing market. The alliance between Compaq and SCO took advantage of this to put out the UnixWare NonStop Clusters product in 1998.[61]

Minor acquisitions centered around building a networking arm and included NetWorth (1998) based in Irving, Texas and Thomas-Conrad (1998) based in Austin, Texas.[63] In 1997, Microcom was also acquired, based in Norwood, MA, which brought a line of modems, Remote Access Servers (RAS) and the popular Carbon Copy software.[64]

In 1998, Compaq acquired Digital Equipment Corporation for a then-industry record of $9.6 billion.[65] The merger made Compaq, at the time, the world's second largest computer maker in the world in terms of revenue behind IBM.[46][19] Digital Equipment, which had nearly twice as many employees as Compaq while generating half the revenue, had been a leading computer company during the 1970s and early 1980s. However, Digital had struggled during the 1990s, with high operating costs. For nine years, the company had lost money or barely broke even, and had recently refocused itself as a "network solutions company". In 1995, Compaq had considered a bid for Digital but only became seriously interested in 1997 after Digital's major divestments and refocusing on the Internet. At the time of the acquisition, services accounted for 45 percent of Digital's revenues (about $6 billion) and their gross margins on services averaged 34 percent, considerably higher than Compaq's 25% margins on PC sales and also satisfying customers who had demanded more services from Compaq for years. Compaq had originally wanted to purchase only Digital's services business but that was turned down.[66] When the announcement was made, it was initially viewed as a master stroke as it immediately gave Compaq a 22,000 person global service operation to help corporations handle major technological purchases (by 2001 services made up over 20% of Compaq's revenues, largely due to the Digital employees inherited from the merger), in order to compete with IBM. However it was also risky merger, as the combined company would have to lay off 2,000 employees from Compaq and 15,000 from Digital which would potentially hurt morale. Furthermore, Compaq fell behind schedule in integrating Digital's operations, which also distracted the company from its strength in low-end PCs where it used to lead the market in rolling out next-generation systems which let rival Dell grab market share.[13][67] Reportedly Compaq had three consulting firms working to integrate Digital alone.[68]

However, Pfeiffer had little vision for what the combined companies should do, or indeed how the three dramatically different cultures could work as a single entity, and Compaq struggled from strategy indecisiveness and lost focus, as a result being caught in between the low end and high end of the market.[69] Mark Anderson, president of Strategic News Service, a research firm based in Friday Harbor, Wash. was quoted as saying, "The kind of goals he had sounded good to shareholders – like being a $50 billion company by the year 2000, or to beat I.B.M. – but they didn't have anything to do with customers. The new C.E.O. should look at everything Eckhard acquired and ask: did the customer benefit from that. If the answer isn't yes, they should get rid of it." On one hand, Compaq had previously dominated the PC market with its price war but was now struggling against Dell, which sold directly to buyers, avoiding the dealer channel and its markup, and built each machine to order to keep inventories and costs at a minimum.[68] At the same time, Compaq, through its acquisitions of the Digital Equipment Corporation in 1998 and Tandem Computers in 1997, had tried to become a major systems company, like IBM and Hewlett-Packard. While IBM and HP were able generate repeat business from corporate customers to drive sales of their different divisions, Compaq had not yet managed to make its newly acquired sales and services organizations work as seamlessly.[70][71]

Ouster of Pfeiffer

[edit]In early 1998, Compaq had the problem of bloated PC inventories. By summer 1998, Compaq was suffering from product-quality problems. Robert W. Stearns, SVP of Business Development, said "In [Pfeiffer's] quest for bigness, he lost an understanding of the customer and built what I call empty market share—large but not profitable", while Jim Moore, a technology strategy consultant with GeoPartners Research in Cambridge, Mass., says Pfeiffer "raced to scale without having economies of scale." The "colossus" that Pfeiffer built up was not nimble enough to adapt to the fast-changing computer industry. That year Compaq forecast demand poorly and shipped too many PCs, causing resellers to dump them at fire sale prices, and since Compaq protected resellers from heavy losses it cost them two quarters of operating profits.[66]

Pfeiffer also refused to develop a potential successor, rebuffing Rosen's suggestion to recruit a few executives to create the separate position of Compaq president. The board complained that Pfeiffer was too removed from management and the rank-and-file, as he surrounded himself with a "clique" of Chief Financial Officer Earl Mason, Senior Vice-President John T. Rose, and Senior Vice-President of Human Resources Hans Gutsch. Current and former Compaq employees complained that Gutsch was part of a group of senior executives, dubbed the "A team", who controlled access to Pfeiffer. Gutsch was said to be a "master of corporate politics, pitting senior vice presidents against each other and inserting himself into parts of the company that normally would not be under his purview". Gutsch, who oversaw security, had an extensive security system and guard station installed on the eight floor of CCA-11, where the company's senior vice presidents worked.[72] There were accusations that Gutsch and others sought to divide top management, although this was regarded by others as sour grapes on the part of executives who were shut out of planning that involved the acquisitions of Tandem Computers and Digital Equipment Corp.[49][73] Pfeiffer reduced the size of the group working on the deal due to news leaks, saying "We cut the team down to the minimum number of people—those who would have to be directly involved, and not one person more". Robert W. Stearns, Compaq's senior vice president for business development, with responsibility for mergers and acquisitions, had opposed the acquisition of Digital as the cultural differences between both companies were too great, and complained that he was placed on the "B team" as a result.[74]

Compaq entered 1999 with strong expectations. Fourth-quarter 1998 earnings reported in January 1999 beat expectations by six cents a share with record 48 percent growth. The company launched Compaq.com as the key for its new direct sales strategy, and planned an IPO for AltaVista toward the end of 1999 in order to capitalize on the dotcom bubble.[75] However, by February 1999, analysts were sceptical of Compaq's plan to sell both direct and to resellers. Compaq was hit with two class-action lawsuits, as a result of CFO Earl Mason, SVP John Rose, and other executives selling US$50 million of stock before a conference call with analysts, where they noted that demand for PCs was slowing down.[76][77][78]

On April 17, 1999, just nine days after Compaq reported first-quarter profit being at half of what analysts had expected, the latest in a string of earnings disappointments, Pfeiffer was forced to resign as CEO in a coup led by board chairman Ben Rosen. Reportedly, at the special board meeting held on April 15, 1999, the directors were unanimous in dismissing Pfeiffer. The company's stock had fallen 50 percent since its all-time high in January 1999.[68] Compaq shares, which traded as high as $51.25 early in 1999, dropped 23 percent on April 12, 1999, the first day of trading after the first-quarter announcement and closed the following Friday at $23.62.[76] During three out of the last six quarters of Pfeiffer's tenure, the company's revenues or earnings had missed expectations.[79] While rival Dell had 55% growth in U.S. PC sales in the first quarter of 1999, Compaq could only manage 10%.[49][70][71][77] Rosen suggested that the accelerating change brought about by the Internet had overtaken Compaq's management team, saying "As a company engaged in transforming its industry for the Internet era, we must have the organizational flexibility necessary to move at Internet speed." In a statement, Pfeiffer said "Compaq has come a long way since I joined the company in 1983" and "under Ben's guidance, I know this company will realize its potential."[80] Rosen's priority was to have Compaq catchup as an E-commerce competitor, and he also moved to streamline operations and reduce the indecision that plagued the company.[49]

Roger Kay, an analyst at International Data Corporation, observed that Compaq's behavior at times seemed like a personal vendetta, noting that "Eckhard has been so obsessed with staying ahead of Dell that they focused too hard on market share and stopped paying attention to profitability and liquidity. They got whacked in a price war that they started."[81] Subsequent earnings releases from Compaq's rivals, Dell, Gateway, IBM, and Hewlett-Packard suggested that the problems were not affecting the whole PC industry as Pfeiffer had suggested.[72] Dell and Gateway sold direct, which helped them to avoid Compaq's inventory problems and compete on price without dealer markups, plus Gateway sold web access and a broad range of software tailored to small businesses. Hewlett-Packard's PC business had similar challenges like Compaq but this was offset by HP's extremely lucrative printer business, while IBM sold PCs at a loss but used them to lock in multi-year services contracts with customers.[66]

After Pfeiffer's resignation, the board established an office of the CEO with a triumvirate of directors; Rosen as interim CEO and vice chairmen Frank P. Doyle and Robert Ted Enloe III.[82] They began "cleaning house", as shortly afterward many of Pfeiffer's top executives resigned or were pushed out, including John J. Rando, Earl L. Mason, and John T. Rose. Rando, senior vice president and general manager of Compaq Services, was a key player during the merger discussions[83] and the most senior executive from Digital to remain with Compaq after the acquisition closed[84][85][86] and had been touted by some as the heir-apparent to Pfeiffer. Rando's division had performed strongly as it had sales of $1.6 billion for the first quarter compared to $113 million in 1998, which met expectations and was anticipated to post accelerated and profitable growth going forward. At the time of Rando's departure, Compaq Services ranked third behind those of IBM and EDS, while slightly ahead of Hewlett-Packard's and Andersen Consulting, however customers switched from Digital technology-based workstations to those of HP, IBM, and Sun Microsystems.[87] Mason, senior vice president and chief financial officer, had previously been offered the job of chief executive of Alliant Foodservice, Inc., a foodservice distributor based in Chicago, and he informed Compaq's board that he accepted the offer.[88][81][89][90] Rose, senior vice president and general manager of Compaq's Enterprise Computing group, resigned effective as of June 3 and was succeeded by Tandem veteran Enrico Pesatori. Rose was reportedly upset that he was not considered for the CEO vacancy, which became apparent once Michael Capellas was named COO. While Enterprise Computing, responsible for engineering and marketing of network servers, workstations and data-storage products, reportedly accounted for one third of Compaq's revenues and likely the largest part of its profits, it was responsible for the earnings shortfall in Q1 of 1999.[91] In addition, Rose was part of the "old guard" close to former CEO Pfeiffer, and he and other Compaq executives had been criticized at the company's annual meeting for selling stock before reporting the sales slowdown.[92] Rose was succeeded by SVP Enrico Pesatori, who had previously worked as a senior executive at Olivetti, Zenith Data Systems, Digital Equipment Corporation, and Tandem Computers.[77] Capellas was appointed COO after pressure mounted on Rosen to find a permanent CEO, however it was reported that potential candidates did not want to work under Rosen as chairman.[75] Around the same time Pesatori was placed in charge of the newly created Enterprise Solutions and Services Group, making him Compaq's second most powerful executive in operational responsibility after Capellas.[93][94]

Pfeiffer's permanent replacement was Michael Capellas, who had been serving as Compaq's SVP and CIO for under a year. A couple months after Pfeiffer's ouster, Capellas was elevated to interim chief operating officer on June 2, 2000,[91] and was soon appointed president and CEO. Capellas also assumed the title of chairman on September 28, 2000, when Rosen stepped down from the board of directors.[11] At his retirement, Rosen proclaimed "These are great achievements—to create 65,000 jobs, $40 billion in sales and $40 billion in market value, all starting with a sketch and a dream".[95]

Late 1990s–2000s

[edit]In 1998, Compaq signed new sales and equipment alliance with NaviSite. Under the pact, Compaq agreed to promote and sell NaviSite Web hosting services. In return, NaviSite took Compaq as a preferred provider for its storage and Intel-based servers.

During November 1999, Compaq began to work with Microsoft to create the first in a line of small-scale, web-based computer systems called MSN Companions.[96]

Struggles

[edit]

Capellas was able to restore some of the luster lost in the latter part of the Pfeiffer era and he repaired the relationship with Microsoft which had deteriorated under his predecessor's tenure.[97]

However Compaq still struggled against lower-cost competitors with direct sales channels such as Dell who took over the top spot of PC manufacturer from Compaq in 2001.[98] Compaq relied significantly on reseller channels, so their criticism caused Compaq to retreat from its proposed direct sales plan, although Capellas maintained that he would use the middlemen to provide value-added services.[79] Despite falling to No. 2 among PC manufacturers, Capellas proclaimed "We are No. 2 in the traditional PC market, but we're focused on industry leadership in the next generation of Internet access devices and wireless mobility. That's where the growth and the profitability will be." The company's longer-term strategy involved extending its services to servers and storage products, as well as handheld computers such as the iPAQ PocketPC which accounted for 11 percent of total unit volume.[99]

Compaq struggled as a result of the collapse of the dot-com bubble, which hurt sales of their high-end systems in 2001 and 2002, and they managed only a small profit in a few quarters during these years. They also accumulated $1.7 billion in short-term debt around this time.[100] The stock price of Compaq, which was around $25 when Capellas became CEO, was trading at half that by 2002.[101]

Acquisition by Hewlett-Packard

[edit]In 2002, Compaq signed a merger agreement with Hewlett-Packard for US$24.2 billion,[101] including US$14.45 billion for goodwill, where each Compaq share would be exchanged for 0.6325 of a Hewlett-Packard share. There would be a termination fee of US$675 million that either company would have to pay the other to break the merger.[102] Compaq shareholders would own 36% of the combined company while HP's would have 64%.[102] Hewlett-Packard had reported yearly revenues of $47 billion, while Compaq's was $40 billion, and the combined company would have been close to IBM's $90 billion revenues. It was projected to have $2.5 billion in annual cost savings by mid-2004. The expected layoffs at Compaq and HP, 8500 and 9000 jobs respectively, would leave the combined company with a workforce of 145,000.[101] The companies would dole out a combined $634.5 million in bonuses to prevent key employees from leaving if shareholders approve the proposed merger, with $370.1 million for HP employees and $264.4 million for Compaq employees.[103][104]

Both companies had to seek approval from their shareholders through separate special meetings.[105] While Compaq shareholders unanimously approved the deal, there was a public proxy battle within HP as the deal was strongly opposed by numerous large HP shareholders, including the sons of the company founders, Walter Hewlett and David W. Packard, as well as the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) and the Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan.[106][107] Walter Hewlett only reluctantly approved the merger, in his duty as a member of the board of directors, since the merger agreement "called for unanimous board approval in order to ensure the best possible shareholder reception".[102] While supporters of the merger argued that there would be economies of scale and that the sales of PCs would drive sales of printers and cameras, Walter Hewlett was convinced that PCs were a low-margin but risky business that would not contribute and would likely dilute the old HP's traditionally profitable Imaging and Printing division.[100][108] David W. Packard in his opposition to the deal "[cited] massive layoffs as an example of this departure from HP’s core values...[arguing] that although the founders never guaranteed job security, 'Bill and Dave never developed a premeditated business strategy that treated HP employees as expendable.'" Packard further stated that "[Carly] Fiorina’s high-handed management and her efforts to reinvent the company ran counter to the company’s core values as established by the founders". The founders' families who controlled a significant amount of HP shares were further irked because Fiorina had made no attempt to reach out to them and consult about the merger, instead they received the same standard roadshow presentation as other investors.[102]

Analysts on Wall Street were generally critical of the merger, as both companies had been struggling before the announcement, and the stock prices of both companies dropped in the months after the merger agreement was made public. Particularly rival Dell made gains from defecting HP and Compaq customers who were wary of the merger.[109] Carly Fiorina, initially seen as HP's savior when she was hired as CEO back in 1999, had seen the company's stock price drop to less than half since she assumed the position, and her job was said to be on shaky ground before the merger announcement.[102] HP's offer was regarded by analysts to be overvaluing Compaq, due to Compaq's shaky financial performance in the past recent years (there were rumors that it could run out of money in 12 months and be forced to cease business operations had it stayed independent), as well as Compaq's own more conservative valuation of its assets.[100][101][110] Detractors of the deal noted that buying Compaq was a "distraction" that would not directly help HP take on IBM's breadth or Dell Computer's direct sales model. Plus there were significant cultural differences between HP and Compaq; which made decisions by consensus and rapid autocratic styles, respectively. One of Compaq's few bright spots was its services business, which was outperforming HP's own services division.[111]

The merger was approved by HP shareholders only after the narrowest of margins,[clarification needed] and allegations of vote buying (primarily involving an alleged last-second back-room deal with Deutsche Bank) haunted the new company. It was subsequently disclosed that HP had retained Deutsche Bank's investment banking division in January 2002 to assist in the merger. HP had agreed to pay Deutsche Bank $1 million guaranteed, and another $1 million contingent upon approval of the merger. On August 19, 2003, the U.S. SEC charged Deutsche Bank with failing to disclose a material conflict of interest in its voting of client proxies for the merger and imposed a civil penalty of $750,000. Deutsche Bank consented without admitting or denying the findings.[112]

Hewlett-Packard announced the completion of merger on May 3, 2002,[113] and the merged HP-Compaq company was officially launched on May 7.[114] Compaq's pre-merger ticker symbol was CPQ. This was combined with Hewlett-Packard's ticker symbol (HWP) to create the current ticker symbol (HPQ), which was announced on May 6.[115]

Post-merger

[edit]Capellas, Compaq's last chairman and CEO, became president of the post-merger Hewlett-Packard, under chairman and CEO Carly Fiorina, to ease the integration of the two companies. However, Capellas was reported not to be happy with his role, being said not to be utilized and being unlikely to become CEO as the board supported Fiorina. Capellas stepped down as HP president on November 12, 2002, after just six months on the job, to become CEO of MCI Worldcom where he would lead its acquisition by Verizon. Capellas' former role of president was not filled as the executives who reported to him then reported directly to the CEO.[116][117]

Fiorina helmed the post-merger HP for nearly three years after Capellas left. HP laid off thousands of former Compaq, DEC, HP, and Tandem employees,[118][119] its stock price generally declined and profits did not perk up. Several senior executives from the Compaq side including Jeff Clarke and Peter Blackmore would resign or be ousted from the post-merger HP.[120] Though the combination of both companies' PC manufacturing capacity initially made the post-merger HP number one, it soon lost the lead and further market share to Dell which squeezed HP on low end PCs.[121][111][122] HP was also unable to compete effectively with IBM in the high-end server market. In addition, the merging of the stagnant Compaq computer assembly business with HP's lucrative printing and imaging division was criticized for obstructing the profitability of the printing/imaging segment.[123] Overall, it has been suggested that the purchase of Compaq was not a good move for HP, due to the narrow profit margins in the commoditized PC business, especially in light of IBM's 2004 announcement to sell its PC division to Lenovo. The Inquirer noted that the continued low return on investment and small margins of HP's personal computer manufacturing business, now named the Personal Systems Group, "continues to be what it was in the individual companies, not much more than a job creation scheme for its employees".[100] One of the few positives was Compaq's sales approach and enterprise focus that influenced the newly combined company's strategy and philosophy.[124]

In February 2005, the board of directors ousted Fiorina, with CFO Robert Wayman being named interim CEO.[125] Former Compaq CEO Capellas was mentioned by some as a potential successor, but several months afterwards, Mark Hurd was hired as president and CEO of HP. Hurd separated the PC division from the imaging and printing division and renamed it the Personal Systems Group, placing it under the leadership of EVP Todd R. Bradley. Hewlett Packard's PC business has since been reinvigorated by Hurd's restructuring and now generates more revenue than the traditionally more profitable printers. By late 2006, HP had retaken the #1 sales position of PCs from Dell, which struggled with missed estimates and poor quality, and held that rank until supplanted in the mid-2010s by Lenovo.

Most Compaq products have been re-branded with the HP nameplate, such as the company's market leading ProLiant server line (now owned by Hewlett Packard Enterprise, which spun off from HP in 2015), while the Compaq brand was repurposed for some of HP's consumer-oriented and budget products, notably Compaq Presario PCs. HP's business computers line was discontinued in favour of the Compaq Evo line, which was initially rebranded HP Compaq but now use brands such as EliteBook and ProBook, among others. HP's Jornada PDAs were replaced by Compaq iPAQ PDAs, which were renamed HP iPAQ. Following the merger, all Compaq computers were shipped with HP software.

In May 2007, HP announced in a press release a new logo for their Compaq Division to be placed on the new model Compaq Presarios.[126]

In 2008, HP reshuffled its business line notebooks. The "Compaq" name from its "HP Compaq" series was originally used for all of HP's business and budget notebooks. However, the HP EliteBook line became the top of the business notebook lineup while the HP Compaq B series became its middle business line.[127] As of early 2009, the "HP ProBook" filled out HP's low end business lineup.[128]

In 2009, HP sold part of Compaq's former headquarters to the Lone Star College System.[129]

On August 18, 2011, then-CEO of HP Léo Apotheker announced plans for a partial or full spinoff of the Personal Systems Group. The PC unit had the lowest profit margin although it accounted for nearly a third of HP's overall revenues in 2010. HP was still selling more PCs than any other vendor, shipping 14.9 million PCs in the second quarter of 2011 (17.5% of the market according to Gartner), while Dell and Lenovo were tied for second place, each with more than a 12% share of the market and shipments of over 10 million units.[130][131] However, the announcement of the PC spinoff (concurrent with the discontinuation of WebOS, and the purchase of Autonomy Corp. for $10 billion) was poorly received by the market, and after Apotheker's ouster, plans for a divestiture were cancelled.[132][133] In March 2012, the printing and imaging division was merged into the PC unit.[123] In October 2012, according to Gartner, Lenovo took the lead as the number one PC manufacturer from HP, while IDC ranked Lenovo just right behind HP.[134] In Q2 2013, Forbes reported that Lenovo ranked ahead of HP as the world's number-one PC supplier.[135]

HP discontinued the Compaq brand name in the United States in 2013. Around that same year, Globalk (a Brazilian-based retailer and licensing management firm) started a partnership with HP to re-introduce the brand with a new line of desktop and laptop computers.[136]

In 2015, Grupo Newsan (an Argentinian-based company) acquired the brand's license, along with a $3 million investment, and developed two new lines of Presario notebooks for the local market over the course of the year.[137][138] However, Compaq's Argentine web site went offline in March 2019. The last archived copy of the site was made in October 2018, which featured the same models introduced in 2016.[139]

In 2018, Ossify Industries (an Indian-based company) entered a licensing agreement with HP to use the Compaq brand name for the distribution and manufacturing of Smart TV sets.[140]

Headquarters

[edit]The Compaq World Headquarters (now HP United States) campus consisted of 80 acres (320,000 m2) of land which contained 15 office buildings, 7 manufacturing buildings, a product conference center, an employee cafeteria, mechanical laboratories, warehouses, and chemical handling facilities.[141][142]

Instead of headquartering the company in a downtown Houston skyscraper, then-CEO Rod Canion chose a West Coast-style campus surrounded by forests, where every employee had similar offices and no-one (not even the CEO) had a reserved parking spot.[13][17] As it grew, Compaq became so important to Houston that it negotiated the expansion of Highway 249 in the late 1980s, and many other technology companies appeared in what became known as the "249 Corridor".[143]

After Canion's ouster, senior vice-president of human resources, Hans W. Gutsch, oversaw the company's facilities and security. Gutsch had an extensive security system and guard station installed on the eight floor of CCA-1, where the company's senior vice presidents had their offices. Eckhard Pfeiffer, president and CEO, introduced a whole series of executive perks to a company that had always had an egalitarian culture; for instance, he oversaw the construction of an executive parking garage, previously parking places had never been reserved.[72][144]

On August 31, 1998, the Compaq Commons was opened in the headquarters campus, which featured a conference center, an employee convenience store, a wellness center, and an employee cafeteria.[145]

In 2009, HP sold part of Compaq's former headquarters to the Lone Star College System.[129] Hewlett Packard Buildings #7 & #8, two eight-story reinforced concrete buildings totaling 450,000 square feet, plus a 1,200-car parking garage and a central chiller plant, were all deemed by the college to be too robust and costly to maintain, and so they were demolished by implosion on September 18, 2011.[146][147][148][149]

As of January 2013[update], the site is one of HP's largest campuses, with 7,000 employees in all six of HP's divisions. The campus was inherited by Hewlett Packard Enterprise, one of the successor companies when HP split into two.[143]

In 2018, Hewlett Packard Enterprise announced the sale of the entire former Compaq HQ campus to Mexican beverage distributor Mexcor.[150]

Competitors

[edit]Compaq originally competed directly against IBM, manufacturing computer systems equivalent with the IBM PC, as well as Apple Computer. In the 1990s, as IBM's own PC division declined, Compaq faced other IBM PC Compatible manufacturers like Dell, Packard Bell, AST Research, and Gateway 2000.

By the mid-1990s, Compaq's price war had enabled it to overtake IBM and Apple, while other IBM PC Compatible manufacturers such as Packard Bell and AST were driven out from the market.

Dell overtook Compaq and became the number-one supplier of PCs in 2001.

At the time of their 2002 merger, Compaq and HP were the second and third largest PC manufacturers, so their combination made them number one. However, the combined HP-Compaq struggled and fell to second place behind Dell from 2003 to 2006. Due to Dell's struggles in late 2006, HP has led all PC vendors from 2007 to 2012.

During its existence as a division of HP, Compaq primarily competed against other budget-oriented personal computer series from manufacturers including Acer, Lenovo, and Toshiba. Most of Compaq's competitors except Dell were later acquired by bigger rivals like Acer (Gateway 2000 and Packard Bell) and Lenovo absorbing IBM's PC division. From 2013 onwards, Lenovo has been the world leader for PCs. [citation needed]

Sponsorship

[edit]Before its merger with HP, Compaq sponsored the Williams Formula One team when it was still powered by BMW engines. HP inherited and continued the sponsorship deal for a few years. Compaq sponsored Queens Park Rangers F.C. for the 1994–95 and 1995–96 seasons.

See also

[edit]- Compaq Portable series

- List of computer system manufacturers

- Market share of personal computer vendors

Notes

[edit]- ^ In 1998, the wordmark received a slight tweak, modifying some of the letterforms.[1]

- ^ Some remnants of Compaq (such as the ProLiant server line) are currently owned by Hewlett Packard Enterprise as of 2017.

References

[edit]- ^ Greene, Tim (June 15, 1998). "Compaq airs post-merger plan". Network World. 15 (24). IDG Publications: 7 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Staff writer (January 2, 2002). "Compaq buys back $1 bln in stock". CNET. Red Ventures.

- ^ Aboard the Columbia, By Bill Machrone, p. 451, Jun 1983, PC Mag.

- ^ "Compaq I Portable computer". Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ The Compaq computer is a full-function portable business computer that resembles the IBM PC in almost every way..., Byte review. Archived May 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Rivkin, Jan W., and Porter, Michael E. Matching Dell, Harvard Business School Case 9-799-158, June 6, 1999.

- ^ Dell Computer Corporation Online Case Archived 2013-01-04 at archive.today. Mhhe.com. Retrieved on 2016-06-10.

- ^ "Hewlett-Packard and Compaq Agree to Merge, Creating $87 Billion Global Technology Leader" (Press release). Hewlett-Packard. September 3, 2001. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ^ "Hewlett-Packard in Deal to Buy Compaq for $25 Billion in Stock". The New York Times. September 4, 2001. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ^ Chris Ziegler (May 23, 2012). "'HP Compaq' branding to end next year, Compaq name will live on for 'basic computing at entry-level pricing'". The Verge. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ a b "Compaq Names Michael Capellas Chairman". H41131.www4.hp.com. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ "Compaq Appoints Michael D. Capellas President and Chief Executive Officer". H41131.www4.hp.com. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Martin Puris – Comeback". Scribd.com. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "COMPAQ COMPUTER CORPORATION | The Handbook of Texas Online| Texas State Historical Association (TSHA)". Tshaonline.org. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "Compaq: From place mat sketch to PC giant". USA Today. September 4, 2001. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- ^ a b [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f "Joseph R. "Rod" Canion". Entrepreneur.com. October 10, 2008. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Compaq Computer Corporation (American corporation) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ a b Ramstad, Evan (January 27, 1998). "Compaq to Acquire Digital, Once an Unthinkable Deal". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ LAURENCE ZUCKERMANPublished: June 16, 1997 (June 16, 1997). "Compaq Computer Looks Back and Sees the Competition Gaining – New York Times". The New York Times. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

((cite news)): CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "BUSINESS PEOPLE; Compaq Founder Shifts to Religion". The New York Times. April 8, 1987.

- ^ but not the only one

- ^ "Loyd Case: A Trip Down Memory Lane with Hewlett-Packard & Compaq". extremetech.com. Archived from the original on January 20, 2008. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Robert X. Cringely. "Real Trouble: How Reverse Engineering May Yet Kill Real Networks". PBS. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Ken Polsson. "Chronology of Personal Computers (1982)". Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Zientara, Marguerite (April 2, 1984). "Q&A: H.L. Sparks". InfoWorld. Vol. 6, no. 14. pp. 84–85. Retrieved February 10, 2015.

- ^ Ward, Ronnie (November 1983). "Levels of PC Compatibility". BYTE. Vol. 8, no. 11. pp. 248–249. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ^ Pollack, Andrew (March 27, 1983). "Big I.B.M. Has Done It Again". The New York Times. p. Section 3, Page 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ Cook, Karen; Langdell, James (January 24, 1984). "PC-Compatible Portables". PC Magazine. Vol. 3, no. 1. p. 39. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- ^ Mace, Scott (January 9–16, 1984). "IBM PC clone makers shun total compatibility". InfoWorld. Vol. 6, no. 2 & 3. pp. 79–81. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c d LaPlante, Alice; Furger, Roberta (January 23, 1989). "Compaq Vying To Become the IBM of the '90s". InfoWorld. pp. 1, 8. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

- ^ a b c Lewis, Peter H. (October 22, 1989). "THE EXECUTIVE COMPUTER; The Race to Market a 486 Machine". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ "PC World – The 25 Greatest PCs of All Time". August 11, 2006. Archived from the original on July 25, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Gates, Bill (March 25, 1997). "Interview: Bill Gates, Microsoft". PC Magazine (Interview). Vol. 16, no. 6. Interviewed by Michael J. Miller. pp. 230–235.

- ^ Bane, Michael (November 20, 1988). "9 Clonemakers Unite to Take On the Industry Giant". Chicago Tribune: 11. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. ProQuest 282556133

- ^ Lewis, Peter H. (October 17, 1989). "Compaq Does It Again". The New York Times: C8. Archived from the original on October 19, 2023.

- ^ Bridges, Linda (March 1, 1999). "Making a Difference". eWeek. Ziff-Davis: 76 – via Gale.

- ^ Thomke, Stefan H. (2007). "Apple PowerBook: Design Quality and Time to Market". Managing Product and Service Department: Text and Cases. McGraw-Hill/Irwin. pp. 59–82. ISBN 9780073023014 – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ Dell, Deborah A. (2000). ThinkPad: A Different Shade of Blue. Sams Publishing. pp. 75–78. ISBN 9780672317569 – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ Hayes, Thomas C. "Pfeiffer". The New York Times. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ a b ""Coming To America: Compaq's European Star". Businessweek. Archived from the original on December 8, 2013.

- ^ "COMPANY NEWS; Compaq Payment To Former Chief". The New York Times. April 2, 1992.

- ^ a b "Compaq Computer Corporation [Archive] - Vintage Computer Forum". www.vcfed.org. Archived from the original on September 18, 2016. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ Lewis, Peter H. (October 25, 1992). "Sound Bytes; He Who Fielded Compaq's 'SWAT Team'". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Hayes, Thomas C. (October 26, 1991). "No Headline". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d Zuckerman, Laurence (June 16, 1997). "Compaq Computer Looks Back and Sees the Competition Gaining". The New York Times.

- ^ Fisher, Lawrence M. (November 6, 1991). "Compaq Computer Outlines New Lower-Cost Approach". The New York Times.

- ^ "Joseph R. "Rod" Canion". Entrepreneur.com. October 10, 2008. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Ben Rosen: The Lion in Winter". Businessweek.com. July 26, 1999. Archived from the original on September 9, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ KIRKPATRICK, DAVID (April 1, 1996). "FAST TIMES AT COMPAQ WITH ECKHARD PFEIFFER AT THE WHEEL, COMPAQ IS PASSING OTHER PC MAKERS. THE COMPANY RECENTLY HIT A SPEED BUMP--BUT THE FUTURE'S SO BRIGHT THE CEO HAS TO WEAR SHADES". Fortune.com. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ Fisher, Lawrence M. (August 16, 1994). "COMPANY NEWS; Wide Range Of Price Cuts By Compaq". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Mcwilliams, Gary (July 31, 1995). "Compaq: All Things To All Networks?". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ Kanellos, Michael (November 28, 1994). "ADI develops offshore sites with Compaq's aid". Computer Reseller News (607). CMP Publications: 26 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Silverman, Dwight (May 15, 1994). "If you have the bucks, here are two monitors to buy". Houston Chronicle. Hearst Communications: F2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Barnes, Katie (September 12, 1995). "Compaq 171FS". PC Magazine. 14 (15). Ziff-Davis: 152 – via Google Books.

- ^ Zuckerman, Laurence (October 25, 1996). "Compaq Shakes Up Its Top Management". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c "Compaq Regroups Into 3 Management Units – New York Times". The New York Times. July 3, 1996. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Compaq At The 'Crossroads'". Businessweek. July 21, 1996. Archived from the original on October 26, 2014. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ Mcwilliams, Gary (July 22, 1996). "Compaq At The 'Crossroads'". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Crothers, Brooke (August 19, 1997). "Compaq partners with SCO". CNet.

- ^ a b Kanellos, Michael (August 19, 1998). "Compaq, SCO team on server technology". CNet.

- ^ "Compaq buys Tandem". cnet. June 23, 1997. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ "COMPAQ COMPUTER TO BUY THOMAS-CONRAD". The New York Times. October 19, 1995. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ "Compaq buys Microcom: Compaq Computer Corp. grabbed for a..." Chicago Tribune. April 10, 1997. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ "Compaq to Acquire Digital". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Eckhard's Gone But the PC Rocks On Compaq's CEO blames his ouster on a savagely competitive industry. But other PC makers are fine". CNN Money. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 15, 2013.

- ^ "Dell Computer Corporation Online Case". Archived from the original on January 4, 2013.

- ^ a b c "CHART: Compaq's Stock Price". Businessweek.com. May 3, 1999. Archived from the original on October 27, 2012. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ 24/7 Wall St. (May 4, 2010). "The 15 Worst CEOs In American History". Business Insider. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

((cite web)): CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hansell, Saul (April 25, 1999). "BUSINESS; Compaq at a Crossroad: The Challenges for the Next Chief". The New York Times. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ a b Fisher, Lawrence M. (April 20, 1999). "Reinventing Compaq: Tasks for Next Chief". The New York Times. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Schism in management blamed for Compaq woes". Archived from the original on April 15, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ "Compaq's Gutsch quits post". Dwightsilverman.com. June 16, 1999. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "Access to Pfeiffer may have been heart of Compaq woes - Amarillo.com - Amarillo Globe-News". Archived from the original on October 7, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ a b "For Compaq, 1999 was the year that wasn't". CNET. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ a b Om Malik. "Compaq's CEO Pfeiffer and CFO Mason resign". Forbes.com. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Compaq's Rose Steps Down as Head Of Firm's Computer-Server Business". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Compaq Computer Corporation - Class Action Case 98CV01148 - Securities Class Action Complaint". Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved November 15, 2013.

- ^ a b "Compaq picks new CEO". Money.cnn.com. July 22, 1999. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ Lohr, Steve (April 19, 1999). "Compaq Computer Ousts Chief Executive". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Compaq ousts CEO in major shakeup". CNET. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ "CEO Pfeiffer is out at Compaq – Apr. 19, 1999". Money.cnn.com. April 19, 1999. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "Full text of "Merging information technology and cultures at Compaq-Digital : case study"". Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ "Compaq sacks 6% to absorb Digital". BBC News. June 12, 1998.

- ^ "Palmer to leave Digital". CNN. June 10, 1998.

- ^ "Compaq Losing A Top Officer". The New York Times. May 12, 1999.

- ^ "Strategic Focus". Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ "Alliant Foodservice, Inc. Names Earl L. Mason as President and Chief Executive Officer". Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ "Compaq management exodus cranking up". CNET. January 2, 2002. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ "Compaq exec steps down". CNET. January 2, 2002. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ a b "Another Top Exec Hits the Road at Compaq". Computergram International. 1999. Archived from the original on September 3, 2015.

- ^ "Compaq names COO, top exec". CNET. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ "Enrico Pesatori: Will he ever be No.1?". ZDNet.

- ^ "Compaq's Enrico the Cloak takes wing". The Register.

- ^ "Compaq: From place mat sketch to PC giant". Usatoday30.usatoday.com. September 4, 2001. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "MSN Web Companion". Archived from the original on February 6, 2012. Retrieved March 4, 2007.

- ^ "Compaq reports drop in revenue". CNET. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Gaither, Chris (April 24, 2001). "TECHNOLOGY; Compaq's Results Fall Short of Estimates". The New York Times.

- ^ "Compaq falls short, lowers guidance". April 23, 2001. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "When HP bought Compaq, did it buy a crock?". The Inquirer. August 10, 2003. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

((cite web)): CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c d Sorkin, Andrew Ross; Norris, Floyd (September 4, 2001). "Hewlett-Packard in Deal to Buy Compaq for $25 Billion in Stock". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ a b c d e "The Hewlett-Packard and Compaq Merger" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 13, 2012. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "On the Money Trail". January 17, 2002.

- ^ Pimentel, Benjamin (October 16, 2001). "Officers named for post-merger HP / Analysts still skeptical about pending deal". Sfgate.

- ^ "Compaq preps for life after HP".

- ^ Crn (December 27, 2001). "Walter Hewlett Files Proxy Against Compaq Merger". Crn.com. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ "Showdown in Silicon Valley: Will Fiorina or Hewlett Win the Battle for H-P Shareholders' Votes? – Knowledge@Wharton". Knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ "The HP-Compaq Merger" (PDF). Cata.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 17, 2012. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "Compaq logs 3Q loss, lowers 4Q target – Oct. 23, 2001". Money.cnn.com. October 23, 2001. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "Hp Compaq-A Failed Merger". Scribd.com. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ a b "HP-Compaq merger: Worth the wait?". CNET. September 3, 2002. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ SEC Press Release: "SEC Brings Settled Enforcement Action Against Deutsche Bank Investment Advisory Unit in Connection with Its Voting of Client Proxies for Merger Transaction; Imposes $750,000 Penalty"

- ^ "HP Closes Compaq Merger". Hewlett-Packard. May 3, 2002. Archived from the original on June 4, 2002. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

((cite web)): CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "The New HP is Ready". Hewlett-Packard. May 7, 2002. Archived from the original on June 1, 2002. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

((cite web)): CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "HP Rings in New Company and New Stock Symbol at NYSE Ceremony". Hewlett-Packard. May 6, 2002. Archived from the original on June 4, 2002. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

((cite web)): CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "TechRepublic – A Resource for IT Professionals". Silicon.com. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ "Guild Companies". Itjungle.com. November 13, 2002. Archived from the original on March 25, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ Wong, Nicole C. "HP hires workers as it lets others go | The San Diego Union-Tribune". Signonsandiego.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "HP turns to "churn" for survival". The Denver Post. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "HP fires Blackmore, other sales executives". August 12, 2004.

- ^ Pimentel, Benjamin (November 22, 2002). "PROFILE / Duane Zitzner / From farmer to valley VP / HP exec goes from milking cows to trying to revive computer sales". Sfgate.

- ^ "HP works to reverse its PC slide". CNET. August 28, 2002. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ a b "HP's printer problem – Fortune Tech". Tech.fortune.cnn.com. March 29, 2012. Archived from the original on July 21, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ^ "The HP-Compaq Merger: Partners Reflect 10 Years Later". September 8, 2011.

- ^ "HP boss Fiorina ousted by board". CNN. February 9, 2005.

- ^ "Connect at the speed of business: HP Feature story (May 2007)" (Press release). Hewlett-Packard. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "HP Debuts HP EliteBook, Expands Business Notebook Portfolio" (Press release). Hewlett-Packard. Retrieved June 17, 2008.

- ^ "HP Unveils HP ProBook Notebook PC Line" (Press release). Hewlett-Packard. Retrieved June 17, 2008.

- ^ a b "LSCS purchases center core of HP north campus" (Press release). Lone Star College System. Retrieved July 21, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "HP kills TouchPad, looks to exit PC business". CNN. August 18, 2011.

- ^ Shah, Agam; Jackson, Joab (August 18, 2011). "HP to spin off PC business, shutter webOS device division". Macworld. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ Worthen, Ben (October 12, 2011). "H-P Rethinks PC Spinoff - WSJ.com". Online.wsj.com. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "HP to Buy Autonomy; Spin Off PC Unit, Stock Dropping". Ibtimes.com. August 18, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ Gupta, Poornima (October 11, 2012). "Lenovo knocks HP from top of global PC market: Gartner". Reuters. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ Lenovo Shares Jump As PC Shipments Overtake HP. 7/11/2013

- ^ "Sobre a Compaq". www.compaq.com.br. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ "Grupo Newsan y HP confirman acuerdo para producir en el paísGrupo Newsan y HP confirman acuerdo para producir en el país". Newsan. Archived from the original on May 30, 2019. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- ^ "Compaq presenta su nueva línea de Notebooks con procesadores Intel® Core de 6ta Generación". Newsan (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May 30, 2019. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- ^ Cuoma. "Compaq". Archived from the original on October 23, 2018. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ "Compaq". compaq.tv. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ "Compaq Computer Corporation—World Headquarters." Matrix Spencer - Matrix Design Companies. Retrieved on August 9, 2009.

- ^ "Compaq Computer Corporation – World Headquarters. "World Globetrotting Satellite imagery" and knowledge from a former employee. CCA1-CCA15 were office buildings, CCM1-CCM7 where the manufacturing buildings

- ^ a b Ryan, Molly (January 25, 2013). "What Houston means to HP: Tech giant opens former Compaq campus doors for rare tour". Houston Business Journal. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David (May 24, 1999). "Eckhard's Gone But the PC Rocks On Compaq's CEO blames his ouster on a savagely competitive industry. But other PC makers are fine". CNN. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013.

- ^ "The Compaq Commons Opens at Company's Worldwide Headquarters in Houston; New Facility Includes Advanced Fitness, Wellness Centers and Aggressive End Hunger Project. - Free Online Library". Thefreelibrary.com. August 31, 1998. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "Former HP Building Implosion". YouTube. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "The Coming Local HP Implosion » Swamplot: Houston's Real Estate Landscape". Swamplot. August 30, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "Hewlett Packard Buildings #7 & #8 - Controlled Demolition, Inc". YouTube. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "COMPAQ: Building implosion, HP and Apple". Dusk Before the Dawn. September 18, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "Hewlett Packard Enterprise Sells Houston Campus". April 2022.

External links

[edit]- HP-Compaq merger (washingtontechnology.com) Archived 2006-06-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Silicon Cowboys (2016) Documentary

- OPEN Book Archived 2017-07-29 at the Wayback Machine – How Compaq Ended IBM's PC Domination and Helped Invent Modern Computing book

- Compaq Alumni Group Archived 2021-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Corporate aspects |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hardware |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Software | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Founders | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Directors |

| ||||||||||||||

| Executive officers |

| ||||||||||||||

| Computer hardware products |

| ||||||||||||||

Consumer electronics and accessories |

| ||||||||||||||

| Other divisions | |||||||||||||||

| Software | |||||||||||||||

| Discontinued products |

| ||||||||||||||

| Closed divisions | |||||||||||||||

| HP CEOs | |||||||||||||||

| Assets | |||||||||||||||

| See also | |||||||||||||||

| Key people |

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instruction set architectures, processors |

| ||||||||

| Computer terminals | |||||||||

| Operating systems | |||||||||

| Programming languages | |||||||||

| Character sets |

| ||||||||

| Bus standards | |||||||||

| Other hardware | |||||||||

| Related topics |

| ||||||||

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Other | |