Constantinian shift is used by some theologians and historians of antiquity to describe the political and theological changes that took place during the 4th-century under the leadership of Emperor Constantine the Great. Rodney Clapp claims that the shift or change started in the year 200.[1] The term was popularized by the Mennonite theologian John H. Yoder.[2] He claims that the change was not just freedom from persecution but an alliance between the State and the Church that led to a kind of Caesaropapism. The claim that there ever was a Constantinian shift has been disputed; Peter Leithart argues that there was a "brief, ambiguous 'Constantinian moment' in the fourth century", but that there was "no permanent, epochal 'Constantinian shift'".[3]

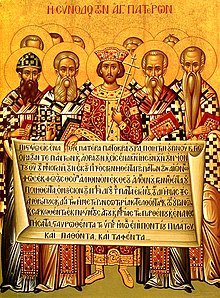

Constantine the Great (reigned 306–337) adopted Christianity as his system of belief after his victory at the Battle of Milvian Bridge in 312.[4][5][6] The following year, 313, he issued the Edict of Milan with his eastern colleague, Licinius. The edict legalised Christianity alongside other religions in the Roman Empire. In 325 the First Council of Nicaea signalled consolidation of Christianity under an orthodoxy endorsed by Constantine. While this did not make other Christian groups outside the adopted definition illegal, dissenting Arian bishops were initially exiled. But Constantine reinstated Arius just before the heresiarch died in 336 and exiled the Orthodox Athanasius of Alexandria from 335 to 337. In 380 Emperor Theodosius I made Christianity the Roman Empire's official religion (see State church of the Roman Empire). In 392 Theodosius passed legislation prohibiting all pagan cultic worship.[7]

During the 4th century, however, there was no real unity between church and state: in the course of the Arian controversy, Arian or semi-Arian emperors exiled leading Trinitarian bishops, such as Athanasius (335, 339, 356, 362, 365), Hilary of Poitiers (356), and Gregory of Nyssa (374[8]); just as leading Arian and Anomoean theologians such as Aëtius (fl. 350) also suffered exile.

Towards the end of the century, Bishop Ambrose of Milan made the powerful Emperor Theodosius I (reigned 379–395) do penance for several months after the massacre of Thessalonica (390) before admitting him again to the Eucharist. On the other hand, only a few years later, Chrysostom, who as bishop of Constantinople criticized the excesses of the royal court, was eventually banished (403) and died (407) while traveling to his place of exile.

| Separation of church and state in the history of the Catholic Church |

|---|

Critics of state-aligned Christianity often point to the ascension of Constantine as the beginning of Caesaropapism: according to this critique, the official Christianity of the Roman state rapidly became a religious and metaphysical justification for the existence, exercise, and expansion of worldly political power, ultimately facilitating earthly Christian empire both for Rome and its successors across Christendom. Similar criticisms are levied by Christian anarchists, who claim that the Constantinian shift triggered the Great Apostasy by transforming the religion into a means for preserving the ruling elite's power and justifying violence.[9]

Augustine of Hippo, who originally had rejected violence in religious matters, later justified it theologically against those he considered heretics, such as the Donatists, who themselves violently harassed their opponents.[10] Before him, Athanasius believed that violence was justified in weeding out heresies that could damn all future Christians.[11] He felt that any means was justified in repressing Arian belief.[12] In 385, Priscillian, a bishop in Spain, was the first Christian to be executed for heresy, though the most prominent church leaders rejected this verdict.

Theologians critical of the Constantinian shift also see it as the point at which membership in the Christian church became associated with a social concept of citizenship, rather than reflecting one's internal decisions and feelings. American theologian Stanley Hauerwas notes the shift as forming part of the foundation for the contemporary American conception of Christianity, one that is closely associated with patriotism and civil religion.[citation needed]